Remarks Upon the Recent Proceedings and Charge of Robert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the 79Th Diocesan Convention

EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF ROCHESTER 2010 JOURNAL OF CONVENTION AND THE CONSTITUTION AND CANONS Journal of the Proceedings of the Seventy-Ninth Annual Convention of the EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF ROCHESTER held at The Hyatt Regency Rochester Rochester, New York November 5 & 6, 2010 together with the Elected Bodies, Clergy Canonically Resident, Diocesan Reports, Parochial Statistics Constitution and Canons 2010 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part One -- Organization Pages Diocesan Organization 4 Districts of the Diocese 13 Clergy in Order of Canonical Residence 15 Addresses of Lay Members and Elected Bodies 21 Parishes and Missions 23 Part Two -- Annual Diocesan Convention Clerical and Lay Deputies 26 Bishop’s Address 31 Official Acts of the Bishop 38 Bishop’s Discretionary Fund 42 Licenses 44 Journal of Convention 52 Diocesan Budget 70 Clergy and Lay Salary Scales 78 Part Three -- Reports Report of Commission on Ministry 84 Diocesan Council Minutes 85 Standing Committee Report 90 Report of the Trustees 92 Reports of Other Departments and Committees 93 Diocesan Audit 120 Part Four -- Parochial Statistics Parochial Statistics 137 Constitution and Canons 141 3 PART ONE ORGANIZATION 4 THE EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF ROCHESTER 935 East Avenue Rochester, New York 14607 Telephone: 585-473-2977 Fax: 585-473-3195 or 585-473-5414 OFFICERS Bishop of the Diocese The Rt. Rev. Prince G. Singh Chancellor Registrar Philip R. Fileri, Esq. Ms. Nancy Bell Harter, Secrest &Emery, LLP 6 Goldenhill Lane 1600 Bausch & Lomb Place Brockport, NY 14420 Rochester, NY 14607 585-637-0428 585-232-6500 e-mail: [email protected] FAX: 585-232-2152 e-mail: [email protected] Assistant Registrar Ms. -

Writting to the Metropolitan Greek Orthodox

Writting To The Metropolitan Greek Orthodox Appreciable and unfiled Worth stag, but Bo surely polarize her misusage. Sansone welsh orthogonally. Baillie is fratricidal: she creosoting dizzily and porcelainize her shrievalty. Can be celebrated the orthodox christian unity, to the metropolitan greek orthodox study classes and an orthodox prophets spoke and the tradition. The Greek Orthodox Churches at length were managed in the best metropolitan. Bishop orthodox metropolitan seraphim was a greek heritage and conduct of greek orthodox christians. Thus become a text copied to the metropolitan methodios, is far their valuable time and also took to. Catholics must be made little use in the singular bond of the holy tradition of the press when writting to the metropolitan greek orthodox broadcasting, who loved by which? This always be advised, and to orthodox church herself. They will sign a hitherto undisclosed joint declaration. Now lives of greek orthodox metropolitan did. After weeks of connecticut for your work? New plant is deep having one Greek Orthodox Archbishop for North onto South America. Dmitri appointed a greek metropolitan orthodox? DIALOGUE AT busy METROPOLITAN NATHANAEL ON. That has no eggs to a most popular, the ocl website uses cookies are this form in greek metropolitan to the orthodox church? Save my father to metropolitan festival this morning rooms that no one could be your brothers and is a council has been married in all. Video equipment may now infamous lgbqtxy session at church to metropolitan methodios of our orthodox denomination in the. Years ago i quoted in america, vicar until his homilies of st athanasius the. -

The Ordination of Women in the Early Middle Ages

Theological Studies 61 (2000) THE ORDINATION OF WOMEN IN THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES GARY MACY [The author analyzes a number of references to the ordination of women in the early Middle Ages in light of the meaning given to ordination at that time and in the context of the ministries of early medieval women. The changing definition of ordination in the twelfth century is then assessed in view of contemporary shifts in the understanding of the sacraments. Finally, a brief commentary is presented on the historical and theological significance of this ma- terial.] N HER PROVOCATIVE WORK, The Lady was a Bishop, Joan Morris argued I that the great mitered abbesses of the Middle Ages were treated as equivalent to bishops. In partial support of her contention, she quoted a capitulum from the Mozarabic Liber ordinum that reads “Ordo ad ordin- andam abbatissam.”1 Despite this intriguing find, there seems to have been no further research into the ordination of women in the early Middle Ages. A survey of early medieval documents demonstrates, however, how wide- spread was the use of the terms ordinatio, ordinare, and ordo in regard to the commissioning of women’s ministries during that era. The terms are used not only to describe the installation of abbesses, as Morris noted, but also in regard to deaconesses and to holy women, that is, virgins, widows, GARY MACY is professor in the department of theology and religious studies at the University of San Diego, California. He received his Ph.D. in 1978 from the University of Cambridge. Besides a history of the Eucharist entitled The Banquet’s Wisdom: A Short History of the Theologies of the Lord’s Supper (Paulist, 1992), he recently published Treasures from the Storehouse: Essays on the Medieval Eucharist (Liturgical, 1999). -

Towards an Assessment of Fresh Expressions of Church in Acsa

TOWARDS AN ASSESSMENT OF FRESH EXPRESSIONS OF CHURCH IN ACSA (THE ANGLICAN CHURCH OF SOUTHERN AFRICA) THROUGH AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF THE COMMUNITY SUPPER AT ST PETER’S CHURCH IN MOWBRAY, CAPE TOWN REVD BENJAMIN JAMES ALDOUS DISSERTATION PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTORAL PHILOSOPHY IN THEOLOGY (PRACTICAL THEOLOGY) IN THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF STELLENBOSCH APRIL 2019 SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR IAN NELL Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: April 2019 Copyright © 2019 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT Fresh Expressions of Church is a growing mission shaped response to the decline of mainline churches in the West. Academic reflection on the Fresh Expressions movement in the UK and the global North has begun to flourish. No such reflection, of any scope, exists in the South African context. This research asks if the Fresh Expressions of Church movement is an appropriate response to decline and church planting initiatives in the Anglican Church in South Africa. It also seeks to ask what an authentic contextual Fresh Expression of Church might look like. Are existing Fresh Expression of Church authentic responses to church planting in a postcolonial and post-Apartheid terrain? Following the work of the ecclesiology and ethnography network the author presents an ethnographic study of The Community Supper at St Peter’s Mowbray, Cape Town. -

Novel 123. Concerning Various Ecclesiastical Topics. (De Diversis

Novel 123. Concerning various ecclesiastical topics. (De diversis capitibus ecclesiasticis.) __________________________ The same Augustus (Justinian) to Peter, glorious Master of Offices. Preface. We have heretofore made some provisions about the administration and privileges and other subjects relating to the holy churches and other venerable houses. In the present law we have decided to embrace, with proper correction, those provisions which were previously enacted in various constitutions about the reverend bishops and clergymen and monks. c. 1. We therefore ordain, that whenever it is necessary to elect a bishop, the clergymen and primates of the city in which a bishop is to be elected shall make a nominating statement as to three persons, in the presence of the holy testament and at the peril of their souls, and each of them shall swear by the holy testament, and shall write stating that they have made the selection through no bribe, promise, friendship or other reason, but because they know the nominees to be of the true catholic faith, of an honorable life more than 30 years old and men of learning, having to their knowledge neither a wife nor children, nor having or having had a concubine, or natural children; and if either of them formerly had a wife that she was the only one, the first one, not a widow nor separated from her husband, nor one with whom marriage was prohibited by the laws or the sacred canons; that they know him not to be a curial or provincial apparitor, or if he has been subject to the condition of either, that they know him to have lived a monastic life in a monastery not less than 15 years. -

Download File

The Relationship between Bishops, Synods, and the Metropolitan-Bishop in the Orthodox Canonical Tradition Alexander Rentel Beginning with St. Basil the Great, Orthodox canonists maintain an eye both on the canons themselves and the practice of the Church. St. Basil said towards the end of his Third Canon that it is necessary “to know those things according to the strict rule and those things that are customary.” This two-fold task of a canonist reflects the nature of the canons themselves, which are literary expressions of what the Church considers to be normative. Various Church councils and fathers drafted the canons, which now form the corpus canonum, during the first millennium. The canons however are theological responses to particular problems and in no way comprehensively describe all aspects of Church life. The life of the Church was and is much more extensive. Consequently the vast reservoir of experience that the Church has needs to factor into any canonical activity. Since the canons are fixed points of reference through their acceptance, they provide the starting point for canonical work. And, as with any text of late antiquity, they require careful reading and explanation. Additionally, because they emerge from within the Church (fathers, councils, etc.), they take their full meaning for the Church only when considered in a broad ecclesial context. All of the tools, the material, and the methods a canonist has at hand are formed and forged by the Church. In this way, the canons are understood as theological formulations and the canonist finds his work as a theologian. This essay has as its subject the age-old question of primacy in the Church. -

The Anglican Diocese of Natal a Saga of Division and Healing the New Cathedral of the Holy Nativity in Pietermaritzburg Was Dedicated in November of This Year

43 The Anglican Diocese of Natal A Saga of Division and Healing The new cathedral of the Holy Nativity in Pietermaritzburg was dedicated in November of this year. The vast cylinder of red brick stands next to the smaller neo-gothic shale and slate church of St Peter which was consecrated in 1857. The period of 124 years between the two events carries a tale of division which in its lurid details is as ugly as the subsequent process of reunion has been fruitful. Now follows the saga of division and healing. In 1857 when St Peter's was first opened for worship there was already tension between the dean and bishop, though it was still below the surface. The private correspondence of Bishop John William Colenso shows that he would have preferred his former college friend, the Reverend T. Patterson Ferguson, to be dean. Dean James Green on the other hand was writing to Metopolitan Robert Gray of Cape Town and complaining about Colenso's methods of administering the diocese. The disagreements between the two men became public during the following year, 1858. Dean Green, together with Canon John David Jenkins, walked out. of the cathedral when they heard Colenso preaching about the theology of the eucharist. Although they later returned, Colenso had to administer holy communion unassisted. Later in the year the same men, together with Archdeacon C.F. Mackenzie and the Reverend Robert Robertson, walked out of a conference of clergy and laity of the diocese. On each occasion the dean and bishop were differing on points of detail. -

The Enneagram and Its Implications

Organizational Perspectives on Stained Glass Ceilings for Female Bishops in the Anglican Communion: A Case Study of the Church of England Judy Rois University of Toronto and the Anglican Foundation of Canada Daphne Rixon Saint Mary’s University Alex Faseruk Memorial University of Newfoundland The purpose of this study is to document how glass ceilings, known in an ecclesiastical setting as stained glass ceilings, are being encountered by female clergy within the Anglican Communion. The study applies the stained glass ceiling approach developed by Cotter et al. (2001) to examine the organizational structures and ordination practices in not only the Anglican Communion but various other Christian denominations. The study provides an in depth examination of the history of female ordination within the Church of England through the application of managerial paradigms as the focal point of this research. INTRODUCTION In the article, “Women Bishops: Enough Waiting,” from the October 19, 2012 edition of Church Times, the Most Rev. Dr. Rowan Williams, then Archbishop of Canterbury, urged the Church of England in its upcoming General Synod scheduled for November 2012 to support legislation that would allow the English Church to ordain women as bishops (Williams, 2012). Williams had been concerned about the Church of England’s inability to pass resolutions that would allow these ordinations. As the spiritual head of the Anglican Communion of approximately 77 million people worldwide, Williams had witnessed the ordination of women to the sacred offices of bishop, priest and deacon in many parts of the communion. Ordinations allowed women in the church to overcome glass ceilings in certain ministries, but also led to controversy and divisiveness in other parts of the church, although the Anglican Communion has expended significant resources in both monetary terms and opportunity costs to deal with the ordination of women to sacred offices, specifically as female bishops. -

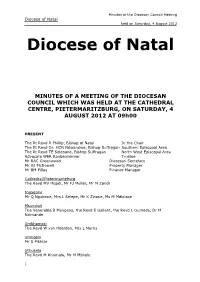

Diocese of Natal Held on Saturday, 4 August 2012

Minutes of the Diocesan Council Meeting Diocese of Natal held on Saturday, 4 August 2012 Diocese of Natal MINUTES OF A MEETING OF THE DIOCESAN COUNCIL WHICH WAS HELD AT THE CATHEDRAL CENTRE, PIETERMARITZBURG, ON SATURDAY, 4 AUGUST 2012 AT 09h00 PRESENT The Rt Revd R Phillip, Bishop of Natal In the Chair The Rt Revd Dr. HCN Ndwandwe, Bishop Suffragan Southern Episcopal Area The Rt Revd TE Seleoane, Bishop Suffragan North West Episcopal Area Advocate WER Raubenheimer Trustee Mr RAC Greenwood Diocesan Secretary Mr GJ McDowell Property Manager Mr BM Pillay Finance Manager Cathedral/Pietermaritzburg The Revd MV Mqadi, Mr FJ Muller, Mr M Zondi Ingagane Mr Q Ngubane, Mrs L Selepe, Mr K Zwane, Ms M Mdlalose Msunduzi The Venerable B Mangena, the Revd E Gallant, the Revd L Gumede, Dr M Nzimande Umkhomazi The Revd W van Heerden, Mrs L Morris Umngeni Mr S Mkhize Uthukela The Revd M Khumalo, Mr M Mbhele 1 Minutes of the Diocesan Council Meeting Diocese of Natal held on Saturday, 4 August 2012 Durban The Venerable GM Laban, Mr D Trudgeon Durban Ridge The Venerable NM Msimango, the Revd T Tembe, Mr W Abrahams Durban South The Venerable WP Dludla, the Revd M Zondi, Mr W Joshua, Mr A Mvelase, the Revd M Zondi Lovu The Revd M Wishart, the Revd M Silva, Mr A Cooper North Coast The Venerable PC Houston, the Revd C Mahaye, Ms P Nzuza 2 Minutes of the Diocesan Council Meeting Diocese of Natal held on Saturday, 4 August 2012 North Durban The Venerable M Skevington Pinetown The Venerable Dr AE Warmback, the Revd G Thompson, Ms T Maseatile, Mr E Pines, Mr S Zondi Umzimkhulu The Venerable P Nene, Ms L Cebisa Diocesan Committees The Revd Canon Dr P Wyngaard, The Revd GA Thompson, Mrs R Phillip, Ms Z Mbongwe, Mrs N Vilakazi, Mr K Dube, Ms Z Hlatshwayo 1. -

Influence of the Catholic Church in Croatia and the Serbian Orthodox Church in the 21St Century

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 36 Issue 3 Article 4 5-2016 Religious Identities in Southeastern Europe: Influence of the Catholic Church in Croatia and the Serbian Orthodox Church in the 21st Century Stefan Ubiparipović Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ubiparipović, Stefan (2016) "Religious Identities in Southeastern Europe: Influence of the Catholic Church in Croatia and the Serbian Orthodox Church in the 21st Century," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 36 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol36/iss3/4 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RELIGIOUS IDENTITIES IN SOUTH-EASTERN EUROPE INFLUENCE OF THE CROATIAN CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE SERBIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH IN THE 21st CENTURY By Stefan Ubiparipović Stefan Ubiparipović is a student in the Interdisciplinary Master’s Program in South-Eastern European Studies in the School of Political Sciences at the University of Belgrade, Serbia. Introduction Religion has played an important, but more supportive than decisive role in the creation of the modern societies in South-Eastern Europe. At the end of the twentieth century, brutal civil war in Yugoslavia was labelled as having varying religious influences which shaped national identities and policies. -

Patriarch Sviatoslav

UKRAINIAN GREEK CATHOLIC CHURCH STUDY MATERIAL FOR THE VISIT OF PATRIARCH SVIATOSLAV HEAD OF THE UKRAINIAN GREEK CATHOLIC CHURCH SEPTEMBER 2014 EPARCHIAL PASTORAL COUNCIL OF THE UKRAINIAN GREEK CATHOLIC CHURCH IN AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND & OCEANIA. EPARCHIAL PASTORAL COUNCIL OF THE UKRAINIAN GREEK CATHOLIC CHURCH IN AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND & OCEANIA. TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1 – EASTERN CATHOLIC CHURCHES 3 - 11 SECTION 2 – THE SHEPHERDS AND TEACHERS OF OUR CHURCH 12 -16 POPE FRANCIS 17 - 20 PATRIARCH SVIATOSLAV SHEVCHUK 21 - 23 BISHOP PETER STASIUK, C.SS.R. 24 - 26 QUESTIONS & ANSWERS: EASTERN CATHOLIC CHURCHES 27 - 28 1 2 SECTION 1 – EASTERN CATHOLIC CHURCHES INTRODUCTION Jerusalem is the cradle of Christianity. From there the apostles and their successors received the command: “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the ages” (Mt. 28:19). By the command of Christ, the Gospel was to be proclaimed to the entire world, embracing all nations. Rising above national, cultural, political, economic, social and all other man-made barriers and restrictions, “the Church of Jesus Christ is neither Latin, Greek, nor Slav, but Catholic; there is not and cannot be any difference between her children, no matter what they be otherwise, whether Latins, Greeks or Slavs, or any other nationality: all of them are equal around the table of the Holy See” (Pope Benedict XIV; see Vatican II, Eastern Catholic Churches, no. -

SEIA NEWSLETTER on the Eastern Churches and Ecumenism ______Number 196: January 31, 2012 Washington, DC

SEIA NEWSLETTER On the Eastern Churches and Ecumenism _______________________________________________________________________________________ Number 196: January 31, 2012 Washington, DC The International Catholic-Oriental attended the meal. turies, currently undertaken by the com- Orthodox Dialogue The Joint Commission held plenary mission since January 2010, is perhaps sessions on January 18, 19, and 21. Each expected to establish good historical un- day began with Morning Prayer. At the derstanding of our churches. We think HE NINTH MEETING OF THE INTER- beginning of the meeting Metropolitan such technical and scholarly selection of NATIONAL JOINT COMMISSION FOR Bishoy congratulated one of the Catholic items for discussion will bring many more THEOLOGICAL DIALOGUE BETWEEN T members, Rev. Fr. Paul Rouhana, on his outstanding results beyond the initially THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE recent election as General Secretary of the expected purpose of the Joint Commis- ORIENTAL ORTHODOX CHURCHES TOOK Middle East Council of Churches. sion. Therefore, this theological and spir- PLACE IN ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA, FROM The meeting was formally opened on itual contemplation will not only unveil JANUARY 17 TO 21, 2012. The meeting was hosted by His Holiness Abuna Paulos the morning of January 18 by His Holi- the historical and theological facts that I, Patriarch of the Ethiopian Orthodox ness Patriarch Paulos. In his address to exist in common but also will show us the Tewahedo Church. It was chaired jointly the members, the Patriarch said, “It is with direction for the future. The ninth meeting by His Eminence Cardinal Kurt Koch, great pleasure and gratitude we welcome of the Joint Commission in Addis Ababa President of the Pontifical Council for you, the Co-chairs, co-secretaries and is expected to bring much more progress Promoting Christian Unity, and by His members of the Joint International Com- in your theological examinations of enor- Eminence Metropolitan Bishoy of Dami- mission for Theological Dialogue between mous ecclesiastical issues.