China After Deng Xiaoping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trapped in a Virtual Cage: Chinese State Repression of Uyghurs Online

Trapped in a Virtual Cage: Chinese State Repression of Uyghurs Online Table of Contents I. Executive Summary..................................................................................................................... 2 II. Methodology .............................................................................................................................. 5 III. Background............................................................................................................................... 6 IV. Legislation .............................................................................................................................. 17 V. Ten Month Shutdown............................................................................................................... 33 VI. Detentions............................................................................................................................... 44 VII. Online Freedom for Uyghurs Before and After the Shutdown ............................................ 61 VIII. Recommendations................................................................................................................ 84 IX. Acknowledgements................................................................................................................. 88 Cover image: Composite of 9 Uyghurs imprisoned for their online activity assembled by the Uyghur Human Rights Project. Image credits: Top left: Memetjan Abdullah, courtesy of Radio Free Asia Top center: Mehbube Ablesh, courtesy of -

China's Global Media Footprint

February 2021 SHARP POWER AND DEMOCRATIC RESILIENCE SERIES China’s Global Media Footprint Democratic Responses to Expanding Authoritarian Influence by Sarah Cook ABOUT THE SHARP POWER AND DEMOCRATIC RESILIENCE SERIES As globalization deepens integration between democracies and autocracies, the compromising effects of sharp power—which impairs free expression, neutralizes independent institutions, and distorts the political environment—have grown apparent across crucial sectors of open societies. The Sharp Power and Democratic Resilience series is an effort to systematically analyze the ways in which leading authoritarian regimes seek to manipulate the political landscape and censor independent expression within democratic settings, and to highlight potential civil society responses. This initiative examines emerging issues in four crucial arenas relating to the integrity and vibrancy of democratic systems: • Challenges to free expression and the integrity of the media and information space • Threats to intellectual inquiry • Contestation over the principles that govern technology • Leverage of state-driven capital for political and often corrosive purposes The present era of authoritarian resurgence is taking place during a protracted global democratic downturn that has degraded the confidence of democracies. The leading authoritarians are ABOUT THE AUTHOR challenging democracy at the level of ideas, principles, and Sarah Cook is research director for China, Hong Kong, and standards, but only one side seems to be seriously competing Taiwan at Freedom House. She directs the China Media in the contest. Bulletin, a monthly digest in English and Chinese providing news and analysis on media freedom developments related Global interdependence has presented complications distinct to China. Cook is the author of several Asian country from those of the Cold War era, which did not afford authoritarian reports for Freedom House’s annual publications, as regimes so many opportunities for action within democracies. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

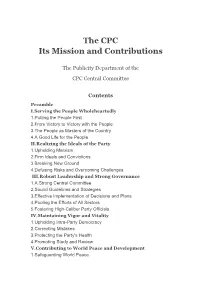

The CPC Its Mission and Contributions

The CPC Its Mission and Contributions The Publicity Department of the CPC Central Committee Contents Preamble I.Serving the People Wholeheartedly 1.Putting the People First 2.From Victory to Victory with the People 3.The People as Masters of the Country 4.A Good Life for the People II.Realizing the Ideals of the Party 1.Upholding Marxism 2.Firm Ideals and Convictions 3.Breaking New Ground 4.Defusing Risks and Overcoming Challenges III.Robust Leadership and Strong Governance 1.A Strong Central Committee 2.Sound Guidelines and Strategies 3.Effective Implementation of Decisions and Plans 4.Pooling the Efforts of All Sectors 5.Fostering High-Caliber Party Officials IV.Maintaining Vigor and Vitality 1.Upholding Intra-Party Democracy 2.Correcting Mistakes 3.Protecting the Party's Health 4.Promoting Study and Review V.Contributing to World Peace and Development 1.Safeguarding World Peace 2.Pursuing Common Development 3.Following the Path of Peaceful Development 4.Building a Global Community of Shared Future Conclusion Preamble The Communist Party of China (CPC), founded in 1921, has just celebrated its centenary. These hundred years have been a period of dramatic change – enormous productive forces unleashed, social transformation unprecedented in scale, and huge advances in human civilization. On the other hand, humanity has been afflicted by devastating wars and suffering. These hundred years have also witnessed profound and transformative change in China. And it is the CPC that has made this change possible. The Chinese nation is a great nation. With a history dating back more than 5,000 years, China has made an indelible contribution to human civilization. -

New Media in New China

NEW MEDIA IN NEW CHINA: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DEMOCRATIZING EFFECT OF THE INTERNET __________________ A University Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, East Bay __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Communication __________________ By Chaoya Sun June 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Chaoya Sun ii NEW MEOlA IN NEW CHINA: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DEMOCRATIlING EFFECT OF THE INTERNET By Chaoya Sun III Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 PART 1 NEW MEDIA PROMOTE DEMOCRACY ................................................... 9 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 9 THE COMMUNICATION THEORY OF HAROLD INNIS ........................................ 10 NEW MEDIA PUSH ON DEMOCRACY .................................................................... 13 Offering users the right to choose information freely ............................................... 13 Making free-thinking and free-speech available ....................................................... 14 Providing users more participatory rights ................................................................. 15 THE FUTURE OF DEMOCRACY IN THE CONTEXT OF NEW MEDIA ................ 16 PART 2 2008 IN RETROSPECT: FRAGILE CHINESE MEDIA UNDER THE SHADOW OF CHINA’S POLITICS ........................................................................... -

China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States

Order Code RL32688 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Updated April 4, 2006 Bruce Vaughn (Coordinator) Analyst in Southeast and South Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Wayne M. Morrison Specialist in International Trade and Finance Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress China-Southeast Asia Relations: Trends, Issues, and Implications for the United States Summary Southeast Asia has been considered by some to be a region of relatively low priority in U.S. foreign and security policy. The war against terror has changed that and brought renewed U.S. attention to Southeast Asia, especially to countries afflicted by Islamic radicalism. To some, this renewed focus, driven by the war against terror, has come at the expense of attention to other key regional issues such as China’s rapidly expanding engagement with the region. Some fear that rising Chinese influence in Southeast Asia has come at the expense of U.S. ties with the region, while others view Beijing’s increasing regional influence as largely a natural consequence of China’s economic dynamism. China’s developing relationship with Southeast Asia is undergoing a significant shift. This will likely have implications for United States’ interests in the region. While the United States has been focused on Iraq and Afghanistan, China has been evolving its external engagement with its neighbors, particularly in Southeast Asia. In the 1990s, China was perceived as a threat to its Southeast Asian neighbors in part due to its conflicting territorial claims over the South China Sea and past support of communist insurgency. -

Digital Neo-Colonialism: the Chinese Model of Internet Sovereignty in Africa

AFRICAN HUMAN RIGHTS LAW JOURNAL To cite: W Gravett ‘Digital neo-colonialism: The Chinese model of internet sovereignty in Africa’ (2020) 20 African Human Rights Law Journal 125-146 http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/1996-2096/2020/v20n1a5 Digital neo-colonialism: The Chinese model of internet sovereignty in Africa Willem Gravett* Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, South Africa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7400-0036 Summary: China is making a sustained effort to become a ‘cyber superpower’. An integral part of this effort is the propagation by Beijing of the notion of ‘internet sovereignty’ – China’s supreme right to govern the internet within its borders and keep it under rigid control. Chinese companies work closely with Chinese state authorities to export technology to Africa in order to extend China’s influence and promote its cyberspace governance model. This contribution argues that the rapid expansion across Africa of Chinese technology companies and their products warrants vigilance. If African governments fail to advance their own values and interests – including freedom of expression, free enterprise and the rule of law – with equal boldness, the ‘China model’ of digital governance by default might very well become the ‘Africa model’. Key words: Chinese internet censorship; data surveillance; digital authoritarianism; digital neo-colonialism; global cyber governance; internet sovereignty * BLC LLB (Pretoria) LLM (Notre Dame) LLD (Pretoria); [email protected]. I gratefully acknowledge the very able and -

Tiktok and Wechat Curating and Controlling Global Information Flows

TikTok and WeChat Curating and controlling global information flows Fergus Ryan, Audrey Fritz and Daria Impiombato Policy Brief Report No. 37/2020 About the authors Fergus Ryan is an Analyst working with the International Cyber Policy Centre at ASPI. Audrey Fritz is a Researcher working with the International Cyber Policy Centre at ASPI. Daria Impiombato is an Intern working with the International Cyber Policy Centre at ASPI. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Danielle Cave and Fergus Hanson for their work on this project. We would also like to thank Michael Shoebridge, Dr Samantha Hoffman, Jordan Schneider, Elliott Zaagman and Greg Walton for their feedback on this report as well as Ed Moore for his invaluable help and advice. We would also like to thank anonymous technically-focused peer reviewers. This project began in 2019 and in early 2020 ASPI was awarded a research grant from the US State Department for US$250k, which was used towards this report. The work of ICPC would not be possible without the financial support of our partners and sponsors across governments, industry and civil society. What is ASPI? The Australian Strategic Policy Institute was formed in 2001 as an independent, non-partisan think tank. Its core aim is to provide the Australian Government with fresh ideas on Australia’s defence, security and strategic policy choices. ASPI is responsible for informing the public on a range of strategic issues, generating new thinking for government and harnessing strategic thinking internationally. ASPI’s sources of funding are identified in our Annual Report, online at www.aspi.org.au and in the acknowledgements section of individual publications. -

How the Chinese Government Fabricates Social Media Posts

American Political Science Review (2017) 111, 3, 484–501 doi:10.1017/S0003055417000144 c American Political Science Association 2017 How the Chinese Government Fabricates Social Media Posts for Strategic Distraction, Not Engaged Argument GARY KING Harvard University JENNIFER PAN Stanford University MARGARET E. ROBERTS University of California, San Diego he Chinese government has long been suspected of hiring as many as 2 million people to surrep- titiously insert huge numbers of pseudonymous and other deceptive writings into the stream of T real social media posts, as if they were the genuine opinions of ordinary people. Many academics, and most journalists and activists, claim that these so-called 50c party posts vociferously argue for the government’s side in political and policy debates. As we show, this is also true of most posts openly accused on social media of being 50c. Yet almost no systematic empirical evidence exists for this claim https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000144 . or, more importantly, for the Chinese regime’s strategic objective in pursuing this activity. In the first large-scale empirical analysis of this operation, we show how to identify the secretive authors of these posts, the posts written by them, and their content. We estimate that the government fabricates and posts about 448 million social media comments a year. In contrast to prior claims, we show that the Chinese regime’s strategy is to avoid arguing with skeptics of the party and the government, and to not even discuss controversial issues. We show that the goal of this massive secretive operation is instead to distract the public and change the subject, as most of these posts involve cheerleading for China, the revolutionary history of the Communist Party, or other symbols of the regime. -

Governance and Politics of China

Copyrighted material – 978–1–137–44527–8 © Tony Saich 2001, 2004, 2011, 2015 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identifi ed as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First edition 2001 Second edition 2004 Third edition 2011 Fourth edition 2015 Published by PALGRAVE Palgrave in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of 4 Crinan Street, London, N1 9XW. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave is a global imprint of the above companies and is represented throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–1–137–44528–5 hardback ISBN 978–1–137–44527–8 paperback This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. -

Speech at a Ceremony Marking the Centenary of the Communist Party of China July 1, 2021

Speech at a Ceremony Marking the Centenary of the Communist Party of China July 1, 2021 Xi Jinping Comrades and friends, Today, the first of July, is a great and solemn day in the history of both the Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Chinese nation. We gather here to join all Party members and Chinese people of all ethnic groups around the country in celebrating the centenary of the Party, looking back on the glorious journey the Party has traveled over 100 years of struggle, and looking ahead to the bright prospects for the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. To begin, let me extend warm congratulations to all Party members on behalf of the CPC Central Committee. On this special occasion, it is my honor to declare on behalf of the Party and the people that through the continued efforts of the whole Party and the entire nation, we have realized the first centenary goal of building a moderately prosperous society in all respects. This means that we have brought about a historic resolution to the problem of absolute poverty in China, and we are now marching in confident strides toward the second centenary goal of building China into a great modern socialist country in all respects. This is a great and glorious accomplishment for the Chinese nation, for the Chinese people, and for the Communist Party of China! Comrades and friends, The Chinese nation is a great nation. With a history of more than 5,000 years, China has made indelible contributions to the progress of human civilization. -

Freedom on the Net 2016

FREEDOM ON THE NET 2016 China 2015 2016 Population: 1.371 billion Not Not Internet Freedom Status Internet Penetration 2015 (ITU): 50 percent Free Free Social Media/ICT Apps Blocked: Yes Obstacles to Access (0-25) 18 18 Political/Social Content Blocked: Yes Limits on Content (0-35) 30 30 Bloggers/ICT Users Arrested: Yes Violations of User Rights (0-40) 40 40 TOTAL* (0-100) 88 88 Press Freedom 2016 Status: Not Free * 0=most free, 100=least free Key Developments: June 2015 – May 2016 • A draft cybersecurity law could step up requirements for internet companies to store data in China, censor information, and shut down services for security reasons, under the aus- pices of the Cyberspace Administration of China (see Legal Environment). • An antiterrorism law passed in December 2015 requires technology companies to cooperate with authorities to decrypt data, and introduced content restrictions that could suppress legitimate speech (see Content Removal and Surveillance, Privacy, and Anonymity). • A criminal law amendment effective since November 2015 introduced penalties of up to seven years in prison for posting misinformation on social media (see Legal Environment). • Real-name registration requirements were tightened for internet users, with unregistered mobile phone accounts closed in September 2015, and app providers instructed to regis- ter and store user data in 2016 (see Surveillance, Privacy, and Anonymity). • Websites operated by the South China Morning Post, The Economist and Time magazine were among those newly blocked for reporting perceived as critical of President Xi Jin- ping (see Blocking and Filtering). www.freedomonthenet.org FREEDOM CHINA ON THE NET 2016 Introduction China was the world’s worst abuser of internet freedom in the 2016 Freedom on the Net survey for the second consecutive year.