Biorxiv 2020-11-09 ICC-MS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effect of Temperature Adaptation on the Ubiquitin–Proteasome Pathway in Notothenioid Fishes Anne E

© 2017. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2017) 220, 369-378 doi:10.1242/jeb.145946 RESEARCH ARTICLE The effect of temperature adaptation on the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway in notothenioid fishes Anne E. Todgham1,*, Timothy A. Crombie2 and Gretchen E. Hofmann3 ABSTRACT proliferation to compensate for the effects of low temperature on ’ There is an accumulating body of evidence suggesting that the sub- aerobic metabolism (Johnston, 1989; O Brien et al., 2003; zero Antarctic marine environment places physiological constraints Guderley, 2004). Recently, there has been an accumulating body – on protein homeostasis. Levels of ubiquitin (Ub)-conjugated proteins, of literature to suggest that protein homeostasis the maintenance of – 20S proteasome activity and mRNA expression of many proteins a functional protein pool has been highly impacted by evolution involved in both the Ub tagging of damaged proteins as well as the under these cold and stable conditions. different complexes of the 26S proteasome were measured to Maintaining protein homeostasis is a fundamental physiological examine whether there is thermal compensation of the Ub– process, reflecting a dynamic balance in synthetic and degradation proteasome pathway in Antarctic fishes to better understand the processes. There are numerous lines of evidence to suggest efficiency of the protein degradation machinery in polar species. Both temperature compensation of protein synthesis in Antarctic Antarctic (Trematomus bernacchii, Pagothenia borchgrevinki)and invertebrates (Whiteley et al., 1996; Marsh et al., 2001; Robertson non-Antarctic (Notothenia angustata, Bovichtus variegatus) et al., 2001; Fraser et al., 2002) and fish (Storch et al., 2005). In notothenioids were included in this study to investigate the zoarcid fishes, it has been demonstrated that Antarctic eelpouts mechanisms of cold adaptation of this pathway in polar species. -

Gene Essentiality Landscape and Druggable Oncogenic Dependencies in Herpesviral Primary Effusion Lymphoma

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05506-9 OPEN Gene essentiality landscape and druggable oncogenic dependencies in herpesviral primary effusion lymphoma Mark Manzano1, Ajinkya Patil1, Alexander Waldrop2, Sandeep S. Dave2, Amir Behdad3 & Eva Gottwein1 Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is caused by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Our understanding of PEL is poor and therefore treatment strategies are lacking. To address this 1234567890():,; need, we conducted genome-wide CRISPR/Cas9 knockout screens in eight PEL cell lines. Integration with data from unrelated cancers identifies 210 genes as PEL-specific oncogenic dependencies. Genetic requirements of PEL cell lines are largely independent of Epstein-Barr virus co-infection. Genes of the NF-κB pathway are individually non-essential. Instead, we demonstrate requirements for IRF4 and MDM2. PEL cell lines depend on cellular cyclin D2 and c-FLIP despite expression of viral homologs. Moreover, PEL cell lines are addicted to high levels of MCL1 expression, which are also evident in PEL tumors. Strong dependencies on cyclin D2 and MCL1 render PEL cell lines highly sensitive to palbociclib and S63845. In summary, this work comprehensively identifies genetic dependencies in PEL cell lines and identifies novel strategies for therapeutic intervention. 1 Department of Microbiology-Immunology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL 60611, USA. 2 Duke Cancer Institute and Center for Genomic and Computational Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA. 3 Department of Pathology, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL 60611, USA. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to E.G. (email: [email protected]) NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | (2018) 9:3263 | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05506-9 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 ARTICLE NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-05506-9 he human oncogenic γ-herpesvirus Kaposi’s sarcoma- (IRF4), a critical oncogene in multiple myeloma33. -

Identification of the Binding Partners for Hspb2 and Cryab Reveals

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2013-12-12 Identification of the Binding arP tners for HspB2 and CryAB Reveals Myofibril and Mitochondrial Protein Interactions and Non- Redundant Roles for Small Heat Shock Proteins Kelsey Murphey Langston Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Microbiology Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Langston, Kelsey Murphey, "Identification of the Binding Partners for HspB2 and CryAB Reveals Myofibril and Mitochondrial Protein Interactions and Non-Redundant Roles for Small Heat Shock Proteins" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 3822. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3822 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Identification of the Binding Partners for HspB2 and CryAB Reveals Myofibril and Mitochondrial Protein Interactions and Non-Redundant Roles for Small Heat Shock Proteins Kelsey Langston A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Julianne H. Grose, Chair William R. McCleary Brian Poole Department of Microbiology and Molecular Biology Brigham Young University December 2013 Copyright © 2013 Kelsey Langston All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Identification of the Binding Partners for HspB2 and CryAB Reveals Myofibril and Mitochondrial Protein Interactors and Non-Redundant Roles for Small Heat Shock Proteins Kelsey Langston Department of Microbiology and Molecular Biology, BYU Master of Science Small Heat Shock Proteins (sHSP) are molecular chaperones that play protective roles in cell survival and have been shown to possess chaperone activity. -

Large-Scale Image-Based Profiling of Single-Cell Phenotypes in Arrayed CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Perturbation Screens

Published online: January 23, 2018 Method Large-scale image-based profiling of single-cell phenotypes in arrayed CRISPR-Cas9 gene perturbation screens Reinoud de Groot1 , Joel Lüthi1,2 , Helen Lindsay1 , René Holtackers1 & Lucas Pelkmans1,* Abstract this reason, CRISPR-Cas9 has been used in large-scale functional genomic screens (Shalem et al, 2015). Most screens performed to High-content imaging using automated microscopy and computer date employ a pooled screening strategy, which can identify genes vision allows multivariate profiling of single-cell phenotypes. Here, that cause differential growth in screening conditions (Koike-Yusa we present methods for the application of the CISPR-Cas9 system et al, 2013; Shalem et al, 2014; Wang et al, 2014). However, in large-scale, image-based, gene perturbation experiments. We pooled screening precludes multivariate profiling of single-cell show that CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene perturbation can be phenotypes. This can be partially overcome by combining pooled achieved in human tissue culture cells in a timeframe that is screening with single-cell RNA-seq, but this does not easily scale compatible with image-based phenotyping. We developed a pipe- to the profiling of thousands of single cells from thousands of line to construct a large-scale arrayed library of 2,281 sequence- perturbations, and is limited to features that can be read from verified CRISPR-Cas9 targeting plasmids and profiled this library RNA transcript profiles (Adamson et al, 2016; Dixit et al, 2016; for genes affecting cellular morphology and the subcellular local- Jaitin et al, 2016; Datlinger et al, 2017). Moreover, sequencing- ization of components of the nuclear pore complex (NPC). -

Seq2pathway Vignette

seq2pathway Vignette Bin Wang, Xinan Holly Yang, Arjun Kinstlick May 19, 2021 Contents 1 Abstract 1 2 Package Installation 2 3 runseq2pathway 2 4 Two main functions 3 4.1 seq2gene . .3 4.1.1 seq2gene flowchart . .3 4.1.2 runseq2gene inputs/parameters . .5 4.1.3 runseq2gene outputs . .8 4.2 gene2pathway . 10 4.2.1 gene2pathway flowchart . 11 4.2.2 gene2pathway test inputs/parameters . 11 4.2.3 gene2pathway test outputs . 12 5 Examples 13 5.1 ChIP-seq data analysis . 13 5.1.1 Map ChIP-seq enriched peaks to genes using runseq2gene .................... 13 5.1.2 Discover enriched GO terms using gene2pathway_test with gene scores . 15 5.1.3 Discover enriched GO terms using Fisher's Exact test without gene scores . 17 5.1.4 Add description for genes . 20 5.2 RNA-seq data analysis . 20 6 R environment session 23 1 Abstract Seq2pathway is a novel computational tool to analyze functional gene-sets (including signaling pathways) using variable next-generation sequencing data[1]. Integral to this tool are the \seq2gene" and \gene2pathway" components in series that infer a quantitative pathway-level profile for each sample. The seq2gene function assigns phenotype-associated significance of genomic regions to gene-level scores, where the significance could be p-values of SNPs or point mutations, protein-binding affinity, or transcriptional expression level. The seq2gene function has the feasibility to assign non-exon regions to a range of neighboring genes besides the nearest one, thus facilitating the study of functional non-coding elements[2]. Then the gene2pathway summarizes gene-level measurements to pathway-level scores, comparing the quantity of significance for gene members within a pathway with those outside a pathway. -

Defining Functional Interactions During Biogenesis of Epithelial Junctions

ARTICLE Received 11 Dec 2015 | Accepted 13 Oct 2016 | Published 6 Dec 2016 | Updated 5 Jan 2017 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms13542 OPEN Defining functional interactions during biogenesis of epithelial junctions J.C. Erasmus1,*, S. Bruche1,*,w, L. Pizarro1,2,*, N. Maimari1,3,*, T. Poggioli1,w, C. Tomlinson4,J.Lees5, I. Zalivina1,w, A. Wheeler1,w, A. Alberts6, A. Russo2 & V.M.M. Braga1 In spite of extensive recent progress, a comprehensive understanding of how actin cytoskeleton remodelling supports stable junctions remains to be established. Here we design a platform that integrates actin functions with optimized phenotypic clustering and identify new cytoskeletal proteins, their functional hierarchy and pathways that modulate E-cadherin adhesion. Depletion of EEF1A, an actin bundling protein, increases E-cadherin levels at junctions without a corresponding reinforcement of cell–cell contacts. This unexpected result reflects a more dynamic and mobile junctional actin in EEF1A-depleted cells. A partner for EEF1A in cadherin contact maintenance is the formin DIAPH2, which interacts with EEF1A. In contrast, depletion of either the endocytic regulator TRIP10 or the Rho GTPase activator VAV2 reduces E-cadherin levels at junctions. TRIP10 binds to and requires VAV2 function for its junctional localization. Overall, we present new conceptual insights on junction stabilization, which integrate known and novel pathways with impact for epithelial morphogenesis, homeostasis and diseases. 1 National Heart and Lung Institute, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. 2 Computing Department, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. 3 Bioengineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. 4 Department of Surgery & Cancer, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. -

Of GTP-Binding Proteins: ARF, ARL, and SAR Proteins

Published Online: 27 February, 2006 | Supp Info: http://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.200512057 JCB: COMMENT Downloaded from jcb.rupress.org on May 9, 2019 <doi>10.1083/jcb.200512057</doi><aid>200512057</aid>Nomenclature for the human Arf family of GTP-binding proteins: ARF, ARL, and SAR proteins Richard A. Kahn,1 Jacqueline Cherfi ls,2 Marek Elias,3 Ruth C. Lovering,4 Sean Munro,5 and Annette Schurmann6 1Department of Biochemistry, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30322 2Laboratoire d’Enzymologie et Biochimie Structurales, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifi que, 91198 Gif-sur-Yvette, France 3Department of Plant Physiology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, 128 44 Prague 2, Czech Republic 4Human Genome Organisation Gene Nomenclature Committee, Galton Laboratory, Department of Biology, University College London, London NW1 2HE, United Kingdom 5Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge CB2 2QH, United Kingdom 6Department of Pharmacology, German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbrücke, D-14558 Nuthetal, Germany The Ras superfamily is comprised of at least four large they have been found to be ubiquitous regulators of membrane families of regulatory guanosine triphosphate–binding traffi c and phospholipid metabolism in eukaryotic cells (for re- views and discussion of Arf actions see Nie et al., 2003; Burd proteins, including the Arfs. The Arf family includes three et al., 2004; Kahn, 2004). Arfs are soluble proteins that translocate different groups of proteins: the Arfs, Arf-like (Arls), and onto membranes in concert with their activation, or GTP bind- SARs. Several Arf family members have been very highly ing. The biological actions of Arfs are thought to occur on mem- conserved throughout eukaryotic evolution and have branes and to result from their specifi c interactions with a large orthologues in evolutionally diverse species. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

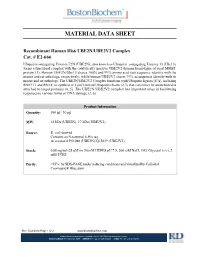

Material Data Sheet

MATERIAL DATA SHEET Recombinant Human His6 UBE2N/UBE2V2 Complex Cat. # E2666 Ubiquitin conjugating Enzyme E2N (UBE2N), also known as Ubiquitin conjugating Enzyme 13 (Ubc13), forms a functional complex with the catalytically inactive UBE2V2 (human homologue of yeast MMS2) protein (1). Human UBE2N/Ubc13 shares 100% and 99% amino acid (aa) sequence identity with the mouse and rat orthologs, respectively, while human UBE2V2 shares 99% aa sequence identity with its mouse and rat orthologs. The UBE2N/UBE2V2 Complex functions with Ubiquitin ligases (E3s), including RNF111 and RNF8, to synthesize Lys63linked Ubiquitin chains (2,3) that can either be unanchored or attached to target proteins (4, 5). The UBE2N/UBE2V2 complex has important roles in facilitating responses to various forms of DNA damage (2, 6). Product Information Quantity: 100 µg | 50 µg MW: 18 kDa (UBE2N), 17 kDa (UBE2V2) Source: E. coliderived Contains an Nterminal 6His tag Accession # P61088 (UBE2N)/Q15819 (UBE2V2) Stock: 0.88 mg/ml (25 μM) in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 10% Glycerol (v/v), 2 mM TCEP Purity: >95%, by SDSPAGE under reducing conditions and visualized by Colloidal Coomassie® Blue stain. Rev. 5/22/2014 Page 1 of 2 www.bostonbiochem.com Boston Biochem products are available via the R&D Systems distributor network. USA & CANADA Tel: (800) 343-7475 EUROPE Tel: +44 (0)1235 529449 CHINA Tel: +86 (21) 52380373 Use & Storage Use: Recombinant Human His6UBE2N/UBE2V2 Complex is a member of the Ubiquitin conjugating (E2) enzyme family that receives Ubiquitin from a Ubiquitin activating (E1) enzyme and subsequently interacts with a Ubiquitin ligase (E3) to conjugate Ubiquitin to substrate proteins. -

![UBE2E1 (Ubch6) [Untagged] E2 – Ubiquitin Conjugating Enzyme](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0534/ube2e1-ubch6-untagged-e2-ubiquitin-conjugating-enzyme-320534.webp)

UBE2E1 (Ubch6) [Untagged] E2 – Ubiquitin Conjugating Enzyme

UBE2E1 (UbcH6) [untagged] E2 – Ubiquitin Conjugating Enzyme Alternate Names: UbcH6, UbcH6, Ubiquitin conjugating enzyme UbcH6 Cat. No. 62-0019-100 Quantity: 100 µg Lot. No. 1462 Storage: -70˚C FOR RESEARCH USE ONLY NOT FOR USE IN HUMANS CERTIFICATE OF ANALYSIS Page 1 of 2 Background Physical Characteristics The enzymes of the ubiquitylation Species: human Protein Sequence: pathway play a pivotal role in a num- GPLGSPGIPGSTRAAAM SDDDSRAST ber of cellular processes including Source: E. coli expression SSSSSSSSNQQTEKETNTPKKKESKVSMSKN regulated and targeted proteasomal SKLLSTSAKRIQKELADITLDPPPNCSAGP degradation of substrate proteins. Quantity: 100 μg KGDNIYEWRSTILGPPGSVYEGGVFFLDIT FTPEYPFKPPKVTFRTRIYHCNINSQGVI Three classes of enzymes are in- Concentration: 1 mg/ml CLDILKDNWSPALTISKVLLSICSLLTDCNPAD volved in the process of ubiquitylation; PLVGSIATQYMTNRAEHDRMARQWTKRYAT activating enzymes (E1s), conjugating Formulation: 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, enzymes (E2s) and protein ligases 150 mM sodium chloride, 2 mM The residues underlined remain after cleavage and removal (E3s). UBE2E1 is a member of the E2 dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol of the purification tag. ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme family UBE2E1 (regular text): Start bold italics (amino acid and cloning of the human gene was Molecular Weight: ~23 kDa residues 1-193) Accession number: AAH09139 first described by Nuber et al. (1996). UBE2E1 shares 74% sequence ho- Purity: >98% by InstantBlue™ SDS-PAGE mology with UBE2D1 and contains an Stability/Storage: 12 months at -70˚C; N-terminal extension of approximately aliquot as required 40 amino acids. A tumour suppressor candidate, tumour-suppressing sub- chromosomal transferable fragment Quality Assurance cDNA (TSSC5) is located in the re- gion of human chromosome 11p15.5 Purity: Protein Identification: linked with Beckwith-Wiedemann syn- 4-12% gradient SDS-PAGE Confirmed by mass spectrometry. -

Gain of UBE2D1 Facilitates Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Zhou et al. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research (2018) 37:290 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-018-0951-8 RESEARCH Open Access Gain of UBE2D1 facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma progression and is associated with DNA damage caused by continuous IL-6 Chuanchuan Zhou1,2, Fengrui Bi1, Jihang Yuan1, Fu Yang1 and Shuhan Sun1* Abstract Background: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of liver cancer with increasing incidence and poor prognosis. Ubiquitination regulators are reported to play crucial roles in HCC carcinogenesis. UBE2D1, one of family member of E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme, mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of tumor suppressor protein p53. However, the expression and functional roles of UBE2D1 in HCC was unknown. Methods: Immunohistochemistry (IHC), western blotting, and real-time PCR were used to detect the protein, transcription and genomic levels of UBE2D1 in HCC tissues with paired nontumor tissues, precancerous lesions and hepatitis liver tissues. Four HCC cell lines and two immortalized hepatic cell lines were used to evaluate the functional roles and underlying mechanisms of UBE2D1 in HCC initiation and progression in vitro and in vivo. The contributors to UBE2D1 genomic amplification were first evaluated by performing a correlation analysis between UBE2D1 genomic levels with clinical data of HCC patients, and then evaluated in HCC and hepatic cell lines. Results: Expression of UBE2D1 was significantly increased in HCC tissues and precancerous lesions and was associated with reduced survival of HCC patients. Upregulation of UBE2D1 promoted HCC growth in vitro and in vivo by decreasing the p53 in ubiquitination-dependent pathway. High expression of UBE2D1 was attributed to the recurrent genomic copy number gain, which was associated with high serum IL-6 level of HCC patients. -

The Ubiquitination Enzymes of Leishmania Mexicana

The ubiquitination enzymes of Leishmania mexicana Rebecca Jayne Burge Doctor of Philosophy University of York Biology October 2020 Abstract Post-translational modifications such as ubiquitination are important for orchestrating the cellular transformations that occur as the Leishmania parasite differentiates between its main morphological forms, the promastigote and amastigote. Although 20 deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) have been partially characterised in Leishmania mexicana, little is known about the role of E1 ubiquitin-activating (E1), E2 ubiquitin- conjugating (E2) and E3 ubiquitin ligase (E3) enzymes in this parasite. Using bioinformatic methods, 2 E1, 13 E2 and 79 E3 genes were identified in the L. mexicana genome. Subsequently, bar-seq analysis of 23 E1, E2 and HECT/RBR E3 null mutants generated in promastigotes using CRISPR-Cas9 revealed that the E2s UBC1/CDC34, UBC2 and UEV1 and the HECT E3 ligase HECT2 are required for successful promastigote to amastigote differentiation and UBA1b, UBC9, UBC14, HECT7 and HECT11 are required for normal proliferation during mouse infection. Null mutants could not be generated for the E1 UBA1a or the E2s UBC3, UBC7, UBC12 and UBC13, suggesting these genes are essential in promastigotes. X-ray crystal structure analysis of UBC2 and UEV1, orthologues of human UBE2N and UBE2V1/UBE2V2 respectively, revealed a heterodimer with a highly conserved structure and interface. Furthermore, recombinant L. mexicana UBA1a was found to load ubiquitin onto UBC2, allowing UBC2- UEV1 to form K63-linked di-ubiquitin chains in vitro. UBC2 was also shown to cooperate with human E3s RNF8 and BIRC2 in vitro to form non-K63-linked polyubiquitin chains, but association of UBC2 with UEV1 inhibits this ability.