Insurance Crimes Alfred Manes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motor Vehicle Insurance Fraud and Related Crimes

2017 Statewide Plan of Operation Detection, Prevention, Deterrence, and Reduction of Motor Vehicle Insurance Fraud and Related Crimes COPYRIGHT NOTICE Copyright 2017 by the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS) This publication may be reproduced without the express written permission of DCJS provided that this copyright notice appears on all copies or segments of the publication. The 2017 edition is published on behalf of the New York State Motor Vehicle Theft and Insurance Fraud Prevention by the: New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services Office of Program Development and Funding Alfred E. Smith Office Building 80 South Swan Street Albany, New York 12210 Table of Contents The Statewide Plan of Operation for Motor Vehicle Insurance Fraud Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 Eligible Programs ................................................................................................. 1 Outline of Statewide Plan ..................................................................................... 1 Part I: Problem Identification of Motor Vehicle Insurance Fraud National Overview ................................................................................................ 3 Statewide Overview .............................................................................................. 3 Part II: Analysis of Motor Vehicle Insurance Fraud in New York State Statewide ............................................................................................................. -

Insurance Fraud Is a Felony

1-800-927-4357 www.insurance.ca.gov Insurance Fraud Is a Felony Dave Jones, Insurance Commissioner California Department of Insurance STATE OF CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF INSURANCE 300 S. Spring Street, South Tower Los Angeles, CA 90013 Dear California Consumer: Thank you for contacting the California Department of Insurance (CDI). As part of our effort to build the best consumer protection agency in the nation, we have created this guide to provide consumers the information and tools to deal effectively with agents, brokers, and insurance companies. We are committed to finding solutions and taking immediate action to help eliminate the many problems now occurring in homeowners, health, and workers’ compensation insurance, as well as consumer privacy protection. These important insurance issues speak to the very fabric of our social economic system and to the future strength of our society and economy in California. Please feel free to contact our Consumer Hotline at 800-927-HELP (4357) if you have further questions about this guide, or if you are experiencing a problem with an agent, broker, or insurance company. The Hotline is staffed by knowledgeable insurance professionals who are ready to assist you with your insurance needs. If you are interested in other insurance topics, CDI has a full range of insurance guides available on our website at www.insurance.ca.gov, or by calling our Consumer Hotline. Thank you for giving us the opportunity to serve you. 3 Table of Contents Fraud Division Overview ...................................................................5 What is Insurance Fraud. ....................................................................7 Insurance Fraud Costs Consumers .................................................9 Common Insurance Fraud Schemes ........................................... 10 Automobile Insurance Fraud........................................................ -

A Consumer Guide to Insurance Fraud

A CONSUMER GUIDE TO INSURANCE FRAUD A CONSUMER GUIDE TO INSURANCE FRAUD INSURANCE ADMINISTRATION A CONSUMER GUIDE TO INSURANCE FRAUD TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . 1 Insurance Fraud . 1 What Is Insurance Fraud? . 2 Consequences of Insurance Fraud . 4 Fraud Against Seniors . 5 Fraud Against Businesses . 6 Drug and Health Discount Programs . 8 Avoid Being A Victim . 9 Additional Tips To Protect Yourself Against Insurance Fraud . 10 What To Do If You Are Involved In An Auto Accident . 12 Report Insurance Fraud . 14 Maryland Insurance Administration • 800-492-6116 • www.insurance.maryland.gov A CONSUMER GUIDE TO INSURANCE FRAUD INTRODUCTION The Maryland Insurance Administration (MIA) is an independent state agency that regulates Maryland’s insurance marketplace and protects consumers by ensuring that insurers and insurance producers (agents and brokers) act in accordance with insurance laws . We produced this guide to help educate Maryland residents about insurance fraud . The Insurance Administration also is responsible for investigating and resolving complaints and questions concerning insurers that conduct business in Maryland . INSURANCE FRAUD Insurance fraud is one of the most costly white-collar crimes in America . Insurance fraud ends up increasing the amount everyone pays in insurance premiums to offset the cost of the fraud . By law, all applications for insurance and all claim forms must contain the following statement, or a substantially similar one: Any person who knowingly and willfully presents a false or fraudulent claim for payment of a loss or benefit or who knowingly and willfully presents false information in an application for insurance is guilty of a crime and may be subject to fines and confinement in prison . -

Cyber-Insurance: Fraud, Waste Or Abuse?

#RSAC SESSION ID: STR-F03 Cyber-Insurance: Fraud, Waste or Abuse? David Nathans Director of Security SOCSoter, Inc. @Zourick #RSAC Cyber Insurance overview One Size Does Not Fit All 2 #RSAC Our Research Reviewed many major policies and some not so major… Spoke with Insurance agencies Spoke with Insurance agents Reviewed policies currently held by customers Got paid by insurance companies to perform Incident Response, forensics and breach analysis 3 #RSAC Types of Insurance Loss of digital assets Damage, alteration, corruption, distortion, theft, misuse, distortion (caused by damage or destruction, operational mistakes, computer crime such as malware, etc) ** NOT RANSOMWARE Non-physical business interruption interruption, degradation in service (caused by damage or destruction, operational mistakes, computer crime such as malware, etc) Cyber Extortion Threat Must get express written consent to pay from insurance company and contact authorities (FBI) all prior to paying any extortion money 4 #RSAC Types of Insurance Security Event Costs / Crisis Management Covers costs associated with resolving a breach, fines by government, regulatory or civil court. Other money for brand harm Network security and privacy Covers claims against you for acts, errors & omissions made by you and your contractors that results in a breach. (Not your breach, this is for a breach you caused somewhere else) 5 #RSAC Types of Insurance Employee Privacy Liability Covers damages to employees resulting in a breach Electronic Media Liability Covers plagiarism or copyright infringement on your website Cyber Terrorism Covers system outage due to terrorism (gov, political, ideological motivation) 6 #RSAC Types of Insurance Identity theft Covers the specific costs associated with notification of victims, credit monitoring, etc. -

Pattern Criminal Jury Instructions for the District Courts of the First Circuit)

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MAINE 2019 REVISIONS TO PATTERN CRIMINAL JURY INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE DISTRICT COURTS OF THE FIRST CIRCUIT DISTRICT OF MAINE INTERNET SITE EDITION Updated 6/24/19 by Chief District Judge Nancy Torresen PATTERN CRIMINAL JURY INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT Preface to 1998 Edition Citations to Other Pattern Instructions How to Use the Pattern Instructions Part 1—Preliminary Instructions 1.01 Duties of the Jury 1.02 Nature of Indictment; Presumption of Innocence 1.03 Previous Trial 1.04 Preliminary Statement of Elements of Crime 1.05 Evidence; Objections; Rulings; Bench Conferences 1.06 Credibility of Witnesses 1.07 Conduct of the Jury 1.08 Notetaking 1.09 Outline of the Trial Part 2—Instructions Concerning Certain Matters of Evidence 2.01 Stipulations 2.02 Judicial Notice 2.03 Impeachment by Prior Inconsistent Statement 2.04 Impeachment of Witness Testimony by Prior Conviction 2.05 Impeachment of Defendant's Testimony by Prior Conviction 2.06 Evidence of Defendant's Prior Similar Acts 2.07 Weighing the Testimony of an Expert Witness 2.08 Caution as to Cooperating Witness/Accomplice/Paid Informant 2.09 Use of Tapes and Transcripts 2.10 Flight After Accusation/Consciousness of Guilt 2.11 Statements by Defendant 2.12 Missing Witness 2.13 Spoliation 2.14 Witness (Not the Defendant) Who Takes the Fifth Amendment 2.15 Definition of “Knowingly” 2.16 “Willful Blindness” As a Way of Satisfying “Knowingly” 2.17 Definition of “Willfully” 2.18 Taking a View 2.19 Character Evidence 2.20 Testimony by Defendant -

Tackling Health Insurance Fraud

SPECIAL FEATURE – CLAIMS Tackling health insurance fraud Mr Colin Weston of RGA looks at what is being done to combat the growing phenomenon of health insurance fraud, and whether more actions are needed. t is impossible to accurately quantify the cost of health Perpetrators and types of fraud insurance fraud but, with real and sustained growth It is known that professional criminals have targeted Iboth of premiums and number of lives covered, the health insurers, in some cases setting up complex frauds. problem is set to escalate. In the US, which spends more These include fraudsters in the UK who, having previously on health than any other country in the world (16.2% of gained access to patients’ insurance details by collaborating GDP in 2009, according to the World Health Organiza- with motorcycle couriers used to transport specimens and tion), it is estimated that between US$68 billion and $175 accounting information, continued to bill unsuspecting in- billion is lost annually to health fraud. surers for a number of years after the closure of a pathology The problem may not be on the same scale in the MENA laboratory. In India, fraudsters targeted a government-run region, but there is already evidence that it is a real concern. scheme for those living below the poverty line by colluding In January 2010, the Health Authority of Abu Dhabi (HAAD) with such residents in the state of Kanpur to submit claims took 39 patients, doctors and insurers to court for a variety for fictitious treatment. of offences, including charging for medical services that had However, the majority of fraud involves real patients who not been provided, making fraudulent claims and using are often unsuspecting bystanders, unaware that anything is fake insurance cards. -

Insurance Fraud… What the Future May Hold

Insurance Fraud… What the Future May Hold THE SURPLUS LINE ASSOCIATION OF CALIFORNIA Tuesday, April 18, 2017, Universal City Wednesday, April 19, 2017, San Francisco Introduction and Overview The New … • Predictive Modeling • Assignment of Benefits (AOB’s) • CEOs going to Jail for Fraud • Financial Fraud at the Corporate Level • Internal ID and Extortion Fraud • Internal Consultants and Internal Fraud • Social Engineering & Wire Fraud • When Good Employees go Bad and the Mundane … • Staged Auto Crashes • Arson © 2016 Fisher Consulting Group, Inc. Reducing the $300B Fraud Industry The Yates Memo • More Intrusive Monitoring - Claims data finds abuse, fraud, and waste Arizona and California Auto Insurance Fraud Busts • Detecting red flags on a fraudulent auto claim • Interdepartmental Co-operation • New “Secret” Device • According to NICB, testers were able to open 54% of the vehicles and drive away with half of them! • Of those driven away, 2/3 were then restarted using the device • Many time the owner believes the vehicle has been towed Identify theft and loss of financial information is one of the primary concerns for those in the financial and retail industries © 2016 Fisher Consulting Group, Inc. The “new normal” 75% of companies surveyed had been victims of fraud in the past year—a 14- percentage point from three 2016 years earlier. 73 * 2015-16 Global fraud report by Kroll, Inc. 75 and The Economist Intelligence Unit 73% of finance 2013 professionals 61 reported an attempted or actual payments fraud in 2015. Victims of Fraud Attempted Fraud *The Association For Financial Victims of Fraud Attempted Fraud Professionals’ 2016 Payments Fraud and Control Survey Source: www.McKinsey.com © 2016 Fisher Consulting Group, Inc. -

Forgery, Fraud and Other Charges As Part of a Scheme to Defraud Their Insurance Carrier

ALBANY COUNTY In the City of Albany, a brother and sister face a range of charges including: forgery, fraud and other charges as part of a scheme to defraud their insurance carrier. Michael and Mary Beth Maxwell are accused of submitting false claims to the Progressive Insurance Company for lost wages totaling $8,711 as the result of an auto accident. The complaint alleges that Mr. Maxwell forged a letter from Ms. Maxwell’s former employer falsely stating that she was scheduled to return to work on December 11, 2002. In reality, Ms. Maxwell was terminated by the employer a month earlier and was not entitled to any lost wages. The defendants are charged with four counts: Forgery in the Second Degree; Insurance Fraud in the Third Degree; Falsifying Business Records in the First Degree; and Attempted Grand Larceny in the Third Degree. BROOME COUNTY In Binghamton, a couple was charged with falsifying records and other charges as part of a scheme to defraud their insurance carrier. Michael DeLuca and Angela Smith are accused of submitting falsified documents to the Liberty Mutual Insurance Company. The couple falsely reported the date of a car accident in order to make a $1,200 claim on an insurance policy that was cancelled because of Ms. Smith’s failure to pay required premiums. The defendants are charged with Insurance Fraud in the Fourth Degree, Falsifying Business Records in the First Degree, Attempted Grand Larceny in the Fourth Degree, Falsely Reporting an Incident in the Third Degree and Conspiracy in the Fifth Degree. In another Broome County case, a Binghamton man was charged in connection with a staged accident in a shopping plaza parking lot. -

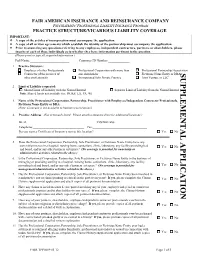

Vicarious Liability Supplemental Application (.Pdf)

FAIR AMERICAN INSURANCE AND REINSURANCE COMPANY PSYCHIATRISTS' PROFESSIONAL LIABILITY INSURANCE PROGRAM PRACTICE STRUCTURE/VICARIOUS LIABILITY COVERAGE IMPORTANT: A copy of the articles of incorporation must accompany the application. A copy of all written agreements which establish the identity of the partnership must accompany the application. Prior to answering any questions referring to any employees, independent contractors, partners, or shareholders, please inquire of each of these individuals as to whether they have information pertinent to the question. (Please print or type all requested information.) Full Name:________________________ Customer ID Number:_____________ 1. Practice Structure: Employer of other Professionals Professional Corporation with more than Professional Partnership/AssociationSUPPL Contractor of the services of one shareholder Fictitious Name Entity or DBASUPPLEMENTAL APPLICATION other professionals Incorporated Solo Private Practice Joint Venture or LLC 2. Limit of Liability requested: Shared Limit of Liability with the Named Insured Separate Limit of Liability from the Named Insured Note: Shared limits not available for: IN, KS, LA, PA, WI E 3. Name of the Professional Corporation, Partnership, Practitioner with Employees/Independent Contractor Professionals, MENTAL APPLICATION Fictitious Name Entity or DBA: __________________________________________________________________________ (Note: Coverage is not available to business corporations.) 4. Practice Address (Not previously listed. Please -

Fraud Facts + Statistics

Facts + Statistics: Fraud Crime + Fraud IN THIS FACTS + STATISTICS Insurance fraud Key State Laws Against Insurance Fraud SHARE THIS DOWNLOAD TO PDF Insurance fraud Insurance fraud is a deliberate deception perpetrated against or by an insurance company or agent for the purpose of financial gain. Fraud may be committed at different points in the insurance transaction by applicants for insurance, policyholders, third-party claimants or professionals who provide services to claimants. Insurance agents and company employees may also commit insurance fraud. Common frauds include “padding,” or inflating actual claims, misrepresenting facts on an insurance application, submitting claims for injuries or damage that never occurred, and “staging” accidents. In 2019, the Coalition Against Insurance Fraud and the SAS Institute published a report entitled, State of Insurance Fraud Technology. The study was based on an online survey of 84 mostly property/casualty insurers conducted in late 2018. Nearly three-quarters of the survey participants said fraud has increased either significantly or slightly in the past three years, an 11-point increase since 2014. No insurer has said that fraud has decreased significantly in the last six years. About 40 percent of insurers polled said their technology budgets for 2019 will be larger, with predictive modeling and link or social network analysis the two most likely types of programs considered for investment. About 90 percent of respondents said they use technology primarily to detect claims fraud, a significant increase from 2016 and about half said they use it to combat underwriting fraud, up from 27 percent in 2016. The greatest challenges for insurers are limited IT resources, which affects about three-quarters of insurers, about the same as in 2016. -

Investigating Life Insurance Fraud and Abuse: Uncovering the Challenges Facing Insurers

Investigating Life Insurance Fraud and Abuse: Uncovering the Challenges Facing Insurers Julianne Callaway, Derek Kueker, Ryan Barker, Mark Dion, Leigh Allen, and Nick Kocisak 1 | Investigating Life Insurance Fraud and Abuse Fraud costs the insurance industry billions of dollars every year. The Coalition Against Insurance Fraud estimates that U.S. insurers lose $80 billion annually to fraud, across all lines of business.1 However, the true cost of fraud is not quantifiable – it extends beyond payment of inappropriate claims and costs to establish fraud prevention and detection units; fraud stifles innovation and fraud costs consumers money and convenience. To better understand the challenges fraud presents, RGA has reached out to life insurers: We surveyed insurance companies,2 conducted informational interviews, held discussions at the 2016 RGA Annual Fraud Conference,3 and conducted our own internal research of claims experience. Types An important first step in understanding fraud is to define it. In this analysis, we are using a broad definition4. Fraud in this context is not limited to criminal activity, but is expanded to include misrepresentations and omissions, whether malicious or less than complete disclosure. Jumbo Violation Paramed Fraud Medical and Stacking Financial Misrepresentation Agent Churning Fraud We discussed the types of fraud with insurers and the associated costs and challenges in detection. Although there was a wide range in responses, medical misrepresentation, agent fraud and criminal fraud were identified as the most concerning types of fraud. Paramed fraud and rebating were identified as the most difficult types of fraud to detect. 1 Coalition Against Insurance Fraud, http://www.insurancefraud.org/statistics.htm#1 2 See Appendix 1 for a description of the survey. -

Insurance Fraud

INSURANCE FRAUD RECOGNIZE IT. REPORT IT. PROTECT YOURSELF. FRAUD CONTROL GROUP The N.C. Department of Insurance would like to thank the North Carolina Association of Insurance Agents, Inc. for its generous support; 1,250 copies of this document were printed using $2,740 of NCAIA Surplus Grant monies. Insurance fraud in North Carolina is big business; in fact, sadly, it is a growing enterprise that costs each of us dearly. With approximately 10 percent of all insurance claims involving some degree of fraud — totaling nearly $120 billion per year lost — we all pay for this deceit in the form of added insurance premiums. Fraud occurs in every area of our insurance needs, from health care insurance to property and casualty insurance, life and disability insurance. Criminals exist with successful scams for every part of the industry, and each of us pay as a result. Also, because North Carolina citizens have endured hurricanes, floods and other natural disasters, we know firsthand that there are opportunists out there who are hitting us while we’re down. Your Department of Insurance is charged with maintaining order in the North Carolina insurance market. I am proud of the fact that our fight to keep insurance rates down has been largely successful, and one of the most important components of the effort to keep these rates down is our fight against fraud. Our Criminal Investigations Division has the mission of conducting criminal investigations and supporting prosecution of persons or other entities committing insurance-related crimes. Department of Insurance Special Agents are committed professionals who are dedicated to our cause and who take pride in our successes.