Conference Committees and Amendments Between the Houses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Shift in the Meaning of Deer Head Sculpture in Javanese House Interior

6th Bandung Creative Movement International Conference in Creative Industries 2019 (6th BCM 2019) A Shift in The Meaning of Deer Head Sculpture in Javanese House Interior Rahmanu Widayat1 1Department of Interior Design, Fakulty of Art and Design, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Surakarta, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract Kejawen community of Java, syncretism from Java, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam possess many kinds decoration in their houses (Javanese houses). One of them is deer head sculpture. Even though it is an imported culture, the deer head sculpture can be easily accepted by the Javanese people because references regarding deer story have been found since the old time. Even though related to deer are quite common, there has not been any research on the shift in the meaning of deer in the context of Javanese culture. The method used in this study is qualitative re- search with the paradigm interpretation. The results of the analysis found that the deer head sculpture, which was originally a preserved and displayed ravin at home as a symbol of prestige, has a connection with Hindu culture, Majapahit culture, Mataram dynasty royal regalia, and Javanese (commonner) Javanese culture. In the context of to- day's modern culture, deer head sculptures are displayed in today's interiors to present a traditional atmosphere and for the sake of nostalgia Keywords meaning, deer head sculture, Javanese house atmosphere of the past. This shows a shift in meaning related 1. Introduction to the deer head sculpture art works. In ancient time, male deer head sculptures were very popular and adorned interior design in many houses of dis- 2. -

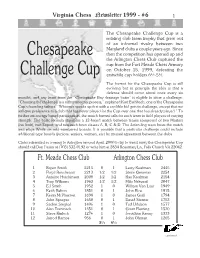

1999/6 Layout

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

Legislative Analysis

Legislative Analysis Mitchell Bean, Director RESTRICT RELEASE OF AUTOPSY PHOTOGRAPHS Phone: (517) 373-8080 http://www.house.mi.gov/hfa House Bill 4249 as enrolled Public Act 322 of 2003 Sponsor: Rep. John Gleason House Committee: Judiciary Senate Committee: Judiciary Third Analysis (12-16-04) BRIEF SUMMARY: The bill would amend sections of the Public Health Code concerning vital records to specify when “autopsy photographs” can be displayed publicly and to allow injured persons, including family members, guardians, and personal representatives, to bring a civil suits against those who publicly display such photographs. FISCAL IMPACT: The bill would have no fiscal impact on the state or local governmental units. THE APPARENT PROBLEM: On December 12, 1996, a young woman from Genesee County died in a drunk driving accident. Devastated by the loss of her daughter, the young woman’s mother visited a number of area high schools to warn students about the dangers of drinking and driving. When she held up a copy of her daughter’s autopsy report during one school visit, a student announced that he had seen photographs of her daughter that had been taken during her autopsy. The woman learned that the autopsy photos were being displayed as part of a “morgue tour” that some county judges required of first-time offenders found guilty of underage possession, drunk driving, and other alcohol-related violations. Defenders of the practice believe that it deters offenders from returning to court, or worse yet, winding up in the morgue themselves. The deceased woman’s family was outraged by the use of their daughter’s body by the courts as a public resource without their consent or knowledge. -

Home Life: the Meaning of Home for People Who Have Experienced Homelessness

Home life: the meaning of home for people who have experienced homelessness By: Sarah Elizabeth Coward A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Social Sciences Department of Sociological Studies September 2018 Abstract ‘Home’ is widely used to describe a positive experience of a dwelling place (shelter). It is about a positive emotional connection to a dwelling place, feeling at ‘home’ in a dwelling place, where both physiological and psychological needs can be fulfilled. This portrayal of ‘home’, however, is not always how a dwelling place is experienced. A dwelling place can be a negative environment, i.e. ‘not-home’, or there may be no emotional attachment or investment in a dwelling place at all. Both circumstances receive little attention in the literature. This research explores the realities of ‘home’ by delving into the ‘home’ lives of seventeen individuals who had experienced a range of different housing situations, including recent homelessness, moving to a (resettlement) sole tenancy and then moving on from that tenancy. Participants were asked to recall their housing histories, from their first housing memory as a child up to the time of interviewing. For each housing episode, they were asked to describe the circumstances of their life at the time, for example relationships, employment and education. They were also asked to reflect on their housing experiences. Similarities and differences of experience are explored according to gender and type of housing situation. This research tells the story of lives characterised by housing and social instability, often triggered by a significant change in social context in childhood. -

Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History

Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Updated February 1, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45087 Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Summary Censure is a reprimand adopted by one or both chambers of Congress against a Member of Congress, President, federal judge, or other government official. While Member censure is a disciplinary measure that is sanctioned by the Constitution (Article 1, Section 5), non-Member censure is not. Rather, it is a formal expression or “sense of” one or both houses of Congress. Censure resolutions targeting non-Members have utilized a range of statements to highlight conduct deemed by the resolutions’ sponsors to be inappropriate or unauthorized. Before the Nixon Administration, such resolutions included variations of the words or phrases unconstitutional, usurpation, reproof, and abuse of power. Beginning in 1972, the most clearly “censorious” resolutions have contained the word censure in the text. Resolutions attempting to censure the President are usually simple resolutions. These resolutions are not privileged for consideration in the House or Senate. They are, instead, considered under the regular parliamentary mechanisms used to process “sense of” legislation. Since 1800, Members of the House and Senate have introduced resolutions of censure against at least 12 sitting Presidents. Two additional Presidents received criticism via alternative means (a House committee report and an amendment to a resolution). The clearest instance of a successful presidential censure is Andrew Jackson. The Senate approved a resolution of censure in 1834. On three other occasions, critical resolutions were adopted, but their final language, as amended, obscured the original intention to censure the President. -

Committee Handbook New Mexico Legislature

COMMITTEE HANDBOOK for the NEW MEXICO LEGISLATURE New Mexico Legislative Council Service Santa Fe, New Mexico 2012 REVISION prepared by: The New Mexico Legislative Council Service 411 State Capitol Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 (505) 986-4600 www.nmlegis.gov 202.190198 PREFACE Someone once defined a committee as a collection of people who individually believe that something must be done and who collectively decide that nothing can be done. Whether or not this definition has merit, it is difficult to imagine the work of a legislative body being accomplished without reliance upon the committee system. Every session, American legislative bodies are faced with thousands of bills, resolutions and memorials upon which to act. Meaningful deliberation on each of these measures by the entire legislative body is not possible. Therefore, the job must be broken up and distributed among the "miniature legislatures" called standing or substantive committees. In New Mexico, where the constitution confines legislative action to a specified number of calendar days, the work of such committees assumes even greater importance. Because the role of committees is vital to the legislative process, it is necessary for their efficient operation that individual members of the senate and house and their staffs understand committee functioning and procedure, as well as their own roles on the committees. For this reason, the legislative council service published in 1963 the first Committee Handbook for New Mexico legislators. This publication is the sixth revision of that document. i The Committee Handbook is intended to be used as a guide and working tool for committee chairs, vice chairs, members and staff. -

Unofficial Journal Copy

Journal of the Senate SECOND REGULAR SESSION TWENTY-EIGHTH DAY—WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2004 The Senate met pursuant to adjournment. Present—Senators Bartle Bland Bray Callahan Senator Shields in the Chair. Caskey Cauthorn Champion Childers Reverend Carl Gauck offered the following Clemens Coleman Days Dolan prayer: Dougherty Foster Gibbons Goode Griesheimer Gross Jacob Kennedy “Rend your hearts and notUnofficial your clothing. Return to the Lord Kinder Klindt Loudon Mathewson Your God, for God is gracious and merciful. Slow to anger and Nodler Quick Russell Scott abounding in steadfast love, and relents from punishing.” (Joel Shields Steelman Stoll Vogel 2:13) Wheeler Yeckel—34 Gracious God, today many observe Ash Wednesday and are Absent with leave—Senators—None called to look at their lives in critical ways. May that be true with us RESOLUTIONS as we pray to You this day, aware of our shortcomings and need of Your mercy. Keep us close O Lord and provide us hope and Senator Days offered Senate Resolution No. Journal1394, regarding Carmen Sandra Morris guidance as we walk through this dark day of ashes. In Your Holy Name we pray. Amen. McClendon, Mayor of the Village of Uplands Park, which was adopted. The Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag was recited. Senator Caskey offered Senate Resolution No. 1395, regarding Mark Dandurand, Warrensburg, A quorum being established, the Senate which was adopted. proceeded with its business. Senator Caskey offered Senate Resolution No. The Journal of the previous dayCopy was read and 1396, regarding Garrett Wayne Depue, approved. Warrensburg, which was adopted. Photographers from the Associated Press and INTRODUCTION OF BILLS KMIZ-TV were given permission to take pictures The following Bills were read the 1st time and in the Senate Chamber today. -

Legislative Process Lpbooklet 2016 15Th Edition.Qxp Booklet00-01 12Th Edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 1

LPBkltCvr_2016_15th edition-1.qxp_BkltCvr00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 2:49 PM Page 1 South Carolina’s Legislative Process LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 1 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 2 October 2016 15th Edition LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 3 THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS The contents of this pamphlet consist of South Carolina’s Legislative Process , pub - lished by Charles F. Reid, Clerk of the South Carolina House of Representatives. The material is reproduced with permission. LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 4 LPBooklet_2016_15th edition.qxp_Booklet00-01 12th edition 11/18/16 3:00 PM Page 5 South Carolina’s Legislative Process HISTORY o understand the legislative process, it is nec - Tessary to know a few facts about the lawmak - ing body. The South Carolina Legislature consists of two bodies—the Senate and the House of Rep - resentatives. There are 170 members—46 Sena - tors and 124 Representatives representing dis tricts based on population. When these two bodies are referred to collectively, the Senate and House are together called the General Assembly. To be eligible to be a Representative, a person must be at least 21 years old, and Senators must be at least 25 years old. Members of the House serve for two years; Senators serve for four years. The terms of office begin on the Monday following the General Election which is held in even num - bered years on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. -

The Impeachment and Trial of a Former President

Legal Sidebari The Impeachment and Trial of a Former President January 15, 2021 For the second time in just over a year, the House of Representatives has voted to impeach President Donald J. Trump. The House previously voted to impeach President Trump on December 18, 2019, and the Senate voted to acquit the President on February 5, 2020. Because the timing of this second impeachment vote is so close to the end of the Trump Administration, it is possible that any resulting Senate trial may not occur until after President Trump leaves office on January 20, 2021. This possibility has prompted the question of whether the Senate can try a former President for conduct that occurred while he was in office. The Constitution’s Impeachment Provisions The Constitution grants Congress authority to impeach and remove the President, Vice President, and other federal “civil Officers” for treason, bribery, or “other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” Impeachment is one of the various checks and balances created by the Constitution, and it serves as a powerful tool for holding government officers accountable. The impeachment process entails two distinct proceedings carried out by the separate houses of Congress. First, a simple majority of the House impeaches—or formally approves allegations of wrongdoing amounting to an impeachable offense. The second proceeding is an impeachment trial in the Senate. If the Senate votes to convict with a two-thirds majority, the official is removed from office. The Senate also can disqualify an official upon conviction from holding a federal office in the future; according to Senate practice, this vote follows the vote for conviction. -

Points of Order; Parliamentary Inquiries

Points of Order; Parliamentary Inquiries A. POINTS OF ORDER § 1. In General; Form § 2. Role of the Chair § 3. Reserving Points of Order § 4. Time to Raise Points of Order § 5. Ð Against Bills and Resolutions § 6. Ð Against Amendments § 7. Application to Particular Questions; Grounds § 8. Relation to Other Business § 9. Debate on Points of Order; Burden of Proof § 10. Waiver of Points of Order § 11. Withdrawal of Points of Order § 12. Appeals B. PARLIAMENTARY INQUIRIES § 13. In General; Recognition § 14. Subjects of Inquiry § 15. Timeliness of Inquiry § 16. As Related to Other Business Research References 5 Hinds §§ 6863±6975 8 Cannon §§ 3427±3458 Manual §§ 627, 637, 861b, 865 A. Points of Order § 1. In General; Form Generally A point of order is in effect an objection that the pending matter or proceeding is in violation of a rule of the House. (Grounds for point of order, see § 7, infra.) Any Member (or any Delegate) may make a point of order. 6 Cannon § 240. Although there have been rare instances in which the Speaker has insisted that the point of order be reduced to writing (5 633 § 1 HOUSE PRACTICE Hinds § 6865), the customary practice is for the Member to rise and address the Chair: MEMBER: Mr. Speaker (or Mr. Chairman), I make a point of order against the [amendment, section, paragraph]. CHAIR: The Chair will hear the gentleman. It is appropriate for the Chair to determine whether the point of order is being raised under a particular rule of the House. The objecting Member should identify the particular rule that is the basis for his point of order. -

2021 Panel Systems Catalog

Table of Contents Page Title Page Number Terms and Conditions 3 - 4 Specifications 5 2.0 and SB3 Panel System Options 16 - 17 Wood Finish Options 18 Standard Textile Options 19 2.0 Paneling System Fabric Panel with Wooden Top Cap 6 - 7 Fabric Posts and Wooden End Caps 8 - 9 SB3 Paneling System Fabric Panel with Wooden Top Cap 10 - 11 Fabric Posts with Wooden Top Cap 12 - 13 Wooden Posts 14 - 15 revision 1.0 - 12/2/2020 Terms and Conditions 1. Terms of Payment ∙Qualified Customers will have Net 30 days from date of order completion, and a 1% discount if paid within 10 days of the invoice date. ∙Customers lacking credentials may be required down payment or deposit in full prior to production. ∙Finance charges of 2% will be applied to each invoice past 30 days. ∙Terms of payment will apply unless modified in writing by Custom Office Design, Inc. 2. Pricing ∙All pricing is premised on product that is made available for will call to the buyer pre-assembled and unpackaged from our base of operations in Auburn, WA. ∙Prices subject to change without notice. Price lists noting latest date supersedes all previously published price lists. Pricing does not include A. Delivery, Installation, or Freight-handling charges. B. Product Packaging, or Crating charges. C. Custom Product Detail upcharge. D. Special-Order/Non-standard Laminate, Fabric, Staining and/or Labor upcharge. E. On-site service charges. F. Federal, state or local taxes. 3. Ordering A. All orders must be made in writing and accompanied with a corresponding purchase order. -

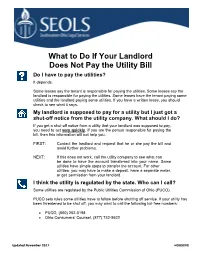

What to Do If Your Landlord Does Not Pay the Utility Bill

What to Do If Your Landlord Does Not Pay the Utility Bill Do I have to pay the utilities? It depends. Some leases say the tenant is responsible for paying the utilities. Some leases say the landlord is responsible for paying the utilities. Some leases have the tenant paying some utilities and the landlord paying some utilities. If you have a written lease, you should check to see what it says. My landlord is supposed to pay for a utility but I just got a shut-off notice from the utility company. What should I do? If you get a shut-off notice from a utility that your landlord was supposed to pay, you need to act very quickly. If you are the person responsible for paying the bill, then this information will not help you. FIRST: Contact the landlord and request that he or she pay the bill and avoid further problems. NEXT: If this does not work, call the utility company to see what can be done to have the account transferred into your name. Some utilities have simple steps to transfer the account. For other utilities, you may have to make a deposit, have a separate meter, or get permission from your landlord. I think the utility is regulated by the state. Who can I call? Some utilities are regulated by the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio (PUCO). PUCO sets rules some utilities have to follow before shutting off service. If your utility has been threatened to be shut off, you may want to call the following toll-free numbers: • PUCO, (800) 282-0198 • Ohio Consumers’ Counsel, (877) 742-5622 Updated November 2017 HOUSING When should I talk to an attorney? You should call an attorney right away if: • You did not get a shut-off notice but the utility was disconnected.