Reclaiming Our Edge: Preservation and Sustainability in Pittsburgh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adaptive Reuse Architecture Documentation and Analysis Dafna Fisher-Gewirtzman* Faculty of Architecture & Town Planning, Technion – IIT, Haifa, Israel

al Eng tur ine ec er Fisher-Gewirtzman, J Archit Eng Tech 2016, 5:3 it in h g c r T e DOI: 10.4172/2168-9717.1000172 A c f h o n Journal of Architectural l o a l n o r g u y o J Engineering Technology ISSN: 2168-9717 Research Article Open Access Adaptive Reuse Architecture Documentation and Analysis Dafna Fisher-Gewirtzman* Faculty of Architecture & Town Planning, Technion – IIT, Haifa, Israel Abstract Buildings have been reused throughout history. The current discourse of diverse trends in preservation together with awareness for sustainable environments has led to a surge in adaptive reuse projects. The combination of new and old architecture ensures the retaining of authentic character while providing an appropriate new use and revitalizing the structure. Learning from precedents is one of the most important knowledge bases for architects. It has many layers of knowledge referring to the old building and its original use, the transformed building and its new use, and the transformation itself. The objective of this work is to propose a theoretical and practical background for a systematic process to support adaptive reuse architecture precedent E-learning. A procedure for the analysis has been developed to fit the specific nature of this architecture data. This paper is presenting the analysis principles and demonstrates the system as a powerful infrastructure for E-learning. Keywords: Adaptive reuse of Buildings; Formal analysis; Learning and to enhance it rather than break it or try to diminish it. Such from precedents; Creative design; Design process structures must be studied carefully for their physical and metaphysical qualities and designers must consider all aspects and decide on tactics Introduction and strategies for their actions. -

Irr Pittsburgh

INTEGRA REALTY RESOURCES IRR PITTSBURGH C O M M E R C I A L R E A L E S T A T E V A L U A T I O N & C O N S U L T I N G 21 years serving Western Pennsylvania market IRR®— INTEGRA REALTY RESOURCES— provides world-class commercial real estate valuation and counseling services to both local and national top financial institutions, developers, corporations, law firms, and government agencies. As one of the largest independent property valuation and counseling firms in the United States, we provide our diverse array of clients the highly informed opinions and trusted expert advice needed to understand the value, use and feasibility of their real estate. IRR. Local expertise. Nationally. 800+ appraisals completed annually 2 INTEGRA REALTY RESOURCES RECENT APPRAISAL ASSIGNMENTS OF NOTABLE AND VARIED ASSETS Office • U.S. Steel Tower, Pittsburgh, PA • Cherrington Corporate Center, Pittsburgh, PA • Foster Plaza Office Center, Pittsburgh, PA • William Penn Plaza, Monroeville, PA • Copperleaf Corporate Center, Wexford, PA • PNC Firstside, Pittsburgh, PA Industrial • Ardex, Aliquippa, PA • Dairy Farmers of America, Sharpsville, PA • Siemens Hunt Valley, Lower Burrell, PA • Universal Well Services, Connellsville, PA • Commonwealth I & II, Wexford, PA • Hunter Trucks, Pittsburgh, PA Multifamily • The Kenmawr Apartments, Pittsburgh, PA • Waterford at Nevillewood, Presto, PA • Cathedral Mansions, Pittsburgh, PA • Vulcan Village, California, PA • Lincoln Pointe Apartments, Bethel Park, PA • Ventana Hills Apartments, Coraopolis, PA Hospitality • Omni William -

An Orientation to Preservation & Adaptive Reuse

MODULE Preservation Toolkit An Orientation to Preservation & 01 Adaptive Reuse Preservation and reuse can mean different things to different people. From “freezing places in time” as a museum, to repairing and adapting places for a new active use. This orientation will introduce you to common preservation terms and resources, explain what listing in the National Register of Historic Places does and does not do, and outline standards for rehabilitation. Background The first noted preservation effort in the United States was Ann Pamela Cunningham and the Mt. Vernon Ladies Association’s crusade in the 1850s to save Mount Vernon. 1906 marked the beginning of the U.S. government’s involvement in historic preservation with the passage of the Antiquities Act and the creation of the National Monuments program. Today, preservation in the United States is guided by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, which introduced Historic Preservation Offices in each state, and created the National Register of Historic Places. Later federal additions to the field include the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards, which guide and promote preservation throughout the country; and Historic Tax Credits, a major incentive for rehabilitation of historic properties. What is Preservation? Preservation “is a movement in planning designed to conserve old buildings and areas in an effort to tie a place’s history to its population and culture. It is also an essential component to green building in that it reuses structures that are already present as opposed to new construction.”1 Preservation compliments the fields of community planning, architecture, and history. Historic buildings and sites embody the story of a place – the values, culture, craftsmanship, and resources of its people. -

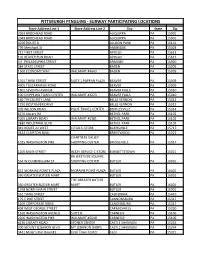

Pittsburgh Penguins

PITTSBURGH PENGUINS - SUBWAY PARTICIPATING LOCATIONS Store Address Line 1 Store Address Line 2 City State Zip 2693 BRODHEAD ROAD ALIQUIPPA PA 15001 2049 BRODHEAD ROAD ALIQUIPPA PA 15001 4706 ROUTE 8 ALLISON PARK PA 15101 799 Merchant St AMBRIDGE PA 15003 211 FIRST STREET APOLLO PA 15613 102 BEAVER RUN ROAD APOLLO PA 15613 5 E. PHILADELPHIA STREET ARMAGH PA 15920 384 STATE STREET BADEN PA 15005 1500 ECONOMY WAY WALMART #4643 BADEN PA 15005 1701 THIRD STREET SUITE 1 PAPPAN PLAZA BEAVER PA 15009 4905 TUSCARAWAS ROAD BEAVER PA 15009 1801 SEVENTH AVENUE BEAVER FALLS PA 15010 100 CHIPPEWA TOWN CENTER WALMART #3223 BEAVER FALLS PA 15010 160 TRI-COUNTY LANE BELLE VERNON PA 15012 1750 ROSTRAVER DRIVE BELLE VERNON PA 15012 205 WILSON ROAD PILOT TRAVEL CENTER BENTLEYVILLE PA 15314 6270 Library Rd BETHEL PARK PA 15102 5055 LIBRARY ROAD WALMART #5381 BETHEL PARK PA 15102 2880 INDUSTRIAL BLVD BETHEL PARK PA 15102 949 ROUTE 22 WEST CITGO C-STORE BLAIRSVILLE PA 15717 4142 CLAIRTON BLVD BRENTWOOD PA 15227 CHARTIERS VALLEY 1025 WASHINGTON PIKE SHOPPING CENTER BRIDGEVILLE PA 15017 1205 MAIN STREET ALEXY SERVICE C-STORE BURGETTSTOWN PA 15021 #A WESTSIDE SQUARE 534 W CUNNINGHAM ST SHOPPING CENTER BUTLER PA 16001 622 MORAINE POINTE PLAZA MORAINE POINT PLAZA BUTLER PA 16001 330 GREATER BUTLER MART BUTLER PA 16001 THE GREATER BUTLER 330 GREATER BUTLER MART MART BUTLER PA 16001 1768 NORTH MAIN STREET BUTLER PA 16001 352 THIRD STREET CALIFORNIA PA 15419 175 E PIKE STREET CANNONSBURG PA 15317 1200 CORPORATE DRIVE CANONSBURG PA 15317 408 WEST GEORGE STREET CARMICHAELS -

Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia Catherine S

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1-1-2005 Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia Catherine S. Jefferson University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Jefferson, Catherine S., "Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia" (2005). Theses (Historic Preservation). 30. http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/30 Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2005. Advisor: David Hollenberg This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/30 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adaptive Reuse: Recent Hotel Conversions in Downtown Philadelphia Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2005. Advisor: David Hollenberg This thesis or dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: http://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/30 ADAPTIVE REUSE: RECENT HOTEL CONVERSIONS IN DOWNTOWN PHILADELPHIA Catherine Sarah Jefferson A THESIS in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION 2005 _____________________________ _____________________________ Advisor Reader David Hollenberg John Milner Lecturer in Historic Preservation Adjunct Professor of Architecture _____________________________ Program Chair Frank G. Matero Associate Professor of Architecture ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the assistance and support of a number of people. -

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 Gamestop Dimond Center 80

Store # Phone Number Store Shopping Center/Mall Address City ST Zip District Number 318 (907) 522-1254 GameStop Dimond Center 800 East Dimond Boulevard #3-118 Anchorage AK 99515 665 1703 (907) 272-7341 GameStop Anchorage 5th Ave. Mall 320 W. 5th Ave, Suite 172 Anchorage AK 99501 665 6139 (907) 332-0000 GameStop Tikahtnu Commons 11118 N. Muldoon Rd. ste. 165 Anchorage AK 99504 665 6803 (907) 868-1688 GameStop Elmendorf AFB 5800 Westover Dr. Elmendorf AK 99506 75 1833 (907) 474-4550 GameStop Bentley Mall 32 College Rd. Fairbanks AK 99701 665 3219 (907) 456-5700 GameStop & Movies, Too Fairbanks Center 419 Merhar Avenue Suite A Fairbanks AK 99701 665 6140 (907) 357-5775 GameStop Cottonwood Creek Place 1867 E. George Parks Hwy Wasilla AK 99654 665 5601 (205) 621-3131 GameStop Colonial Promenade Alabaster 300 Colonial Prom Pkwy, #3100 Alabaster AL 35007 701 3915 (256) 233-3167 GameStop French Farm Pavillions 229 French Farm Blvd. Unit M Athens AL 35611 705 2989 (256) 538-2397 GameStop Attalia Plaza 977 Gilbert Ferry Rd. SE Attalla AL 35954 705 4115 (334) 887-0333 GameStop Colonial University Village 1627-28a Opelika Rd Auburn AL 36830 707 3917 (205) 425-4985 GameStop Colonial Promenade Tannehill 4933 Promenade Parkway, Suite 147 Bessemer AL 35022 701 1595 (205) 661-6010 GameStop Trussville S/C 5964 Chalkville Mountain Rd Birmingham AL 35235 700 3431 (205) 836-4717 GameStop Roebuck Center 9256 Parkway East, Suite C Birmingham AL 35206 700 3534 (205) 788-4035 GameStop & Movies, Too Five Pointes West S/C 2239 Bessemer Rd., Suite 14 Birmingham AL 35208 700 3693 (205) 957-2600 GameStop The Shops at Eastwood 1632 Montclair Blvd. -

20-Century Building Adaptive-Reuse: Office Buildings Converted to Apartments

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2020 20-Century Building Adaptive-Reuse: Office Buildings Converted to Apartments. Yujia Zhang Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Zhang, Yujia, "20-Century Building Adaptive-Reuse: Office Buildings Converted to Apartments." (2020). Theses (Historic Preservation). 697. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/697 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/697 For more information, please contact [email protected]. 20-Century Building Adaptive-Reuse: Office Buildings Converted to Apartments. Abstract Adaptive re-use is a solution to avoiding the obsolescence of buildings in urban development. It is beneficial for the city, for the culture, for the environment, and for the building itself. Recently in the United States, historical office buildings converted into apartments have demonstrated a way to extend the life of these buildings. This thesis aims to analyze 20-century office buildings in Nework Y City converted to apartments in order to examine the possibility of this kind of adaptive-reuse solution for historic office buildings in China. It investigates the history, policy, and design of adaptive-reuse of 20th-Century New York City office building into residential apartments for 21th-century living. It analyzes three cases to understand the requirements for a successful building transformation and speculates about future potential for adaptive re-use of modern office buildings. In addition, it identifies reasons why modern Chinese cities lack similar conversion projects and speculates on whether Chinese cities are suitable for adaptive re-use strategies like those developed in the United States. -

MANAGING CHANGE: Preservation and Rightsizing in America Chairman’S Message

MANAGING CHANGE: Preservation and Rightsizing in America Chairman’s Message The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP) is pleased to present this report addressing rightsizing and historic preservation in America. This issue of rightsizing and its implications for historic preservation have been the focus of considerable attention since 2011 when the devastating effects of the economic downturn on historic properties within legacy cities became apparent to the preservation community. Residents urged the ACHP to assist in managing the effects of major changes occurring to historic properties in local neighborhoods across the country. Recognizing the important role the ACHP could play in advising stakeholders on how to incorporate historic preservation goals and requirements into community efforts, I designated a task force in 2011 to address this issue. The result of our efforts is incorporated in this report, Managing Change: Preservation and Rightsizing in America, which makes key recommendations for ensuring that historic preservation is a vital part of the solution for communities looking to reinvent themselves. The report documents the ACHP’s findings based on site visits to legacy cities, participation in conferences and meetings, and research. In addition, it makes recommendations to federal agencies and the diverse stakeholders involved in rightsizing in legacy cities and other communities. The phenomenon of rightsizing is similar to challenges presented decades ago by the Urban Renewal Program that resulted in the substantial loss of local historic assets. The lessons learned during that period have positioned us now to ensure that historic preservation informs the revitalization of our communities and is not considered an impediment to economic recovery. -

A Study Examining Residential Adaptive Reuse in Downtown Buildings Sponsored by the Pittsburgh Downtown Living Initiative, June 2004 Allegheny River Olive Or Twist

the VACANT UPPER FLOORS project a study examining residential adaptive reuse in downtown buildings sponsored by the pittsburgh downtown living initiative, june 2004 Allegheny River Art Institute Building Olive Or Twist Primanti’s Building One Market Street Monongahela River Buhl Building 02 PREFACE WHAT IS THE VACANT UPPER FLOORS PROJECT? The Vacant Upper Floors project was sponsored by the Downtown Living Initiative of Pittsburgh, and its working group consisted of real estate experts, architects, contractors and building owners united under a single mandate: to show that residential conversion of buildings Downtown is a profitable strategy. The result, which you have here before you in the form of this study, reflects the wisdom, hard work, and practical experience of each one of those team members. The goals of this report are two-fold: • To provide a guide and resource with sufficient technical information for the building owners who were selected to be part of this study, so that they might consider converting their buildings as suggested. • To encourage other building owners to give serious thought to similar conversion scenarios by demonstrating the economic viability (and benefits) of such an undertaking. WHO MIGHT THIS REPORT APPEAL TO? • A building owner whose property is currently all, mostly, or even partially vacant, and who would like to maximize its asset value and income producing potential • Someone who has always wanted to live Downtown • Someone who would like to own a penthouse apartment, and also rent out the remaining floors for an income base • A building owner with a retail establishment on the ground floor, but open warehouse or storage on the upper floors • An investor interested in procuring and developing Downtown properties WHAT SHOULD I LOOK FOR IN MY BUILDING? We thought it appropriate to seed this report with assorted ideas about what to look for in your own building. -

Meditations on Selle Generator Works and Adaptive Reuse Practice

MEDITATIONS ON SELLE GENERATOR WORKS AND ADAPTIVE REUSE PRACTICE A thesis submitted to the Kent State University Honors College in partial fulfillment for the requirements for University Honors (or General or Departmental Honors, as appropriate) by Abby M. Baker May, 2015 Thesis written by Abby M. Baker Approved by ___________________________________________________________________, Jonathan Fleming, Advisor ______________________________________________, Jonathan Fleming, Chair, Department of Architecture Accepted by _____________________________________Donald Palmer, Dean, Honors College II TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES.............................................................................................. IIX ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................. X CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION....................................................................... 1 II DEFINING ADAPTIVE REUSE................................................ 5 A History of Adaptive Reuse....................................................... 7 Adaptive Reuse Today................................................................. 17 III. SELLE GENERATOR WORKS................................................. 31 A History of Selle Generator Works............................................ 33 IV. MEDITATIONS.......................................................................... 47 V. CONCLUSION.......................................................................... 57 WORKS CITED................................................................................................ -

MMW Letter 120506

Macy’s Midwest Conversion to Federated Systems January 16, 2007 See most recent change below Dear Vendor, We are entering the final phase of the integration of Federated-May. Macy’s Midwest (MMW), formerly Famous Barr, will convert to Federated systems on February 4, 2007. The conversion includes EDI and the obligation to comply with the Federated Vendor Standards manual, which is available at www.fdsnet.com. Also, as part of this conversion, 22 locations formerly included in Macy’s South (MSO) will move to MMW and MMW has one location realigning to MSO. To help you prepare for this last phase of the integration, we have attached listings of the MMW stores with their new location numbers and their new EDI mailbox IDs. We are requesting that you share this information with the appropriate persons within your organization. Distribution center (DC) listings and ship to addresses have now been added to the store listings. Please make note of the new ship to locations and the DC Alpha Codes. Changes effective February 4, 2007: • Eight locations originally communicated as being serviced by the Bridgeton DC will now be serviced by the Bailey Road DC See attached matrix for store locations impacted and updated DC alpha codes Please keep in mind that each purchase order is your guide as to when, where and how you are to ship that merchandise. Be aware that purchase orders for MMW may now be received from new Federated sender/receiver EDI IDs. MMW may also issue purchase orders from their current May system with ship dates after the February 4, 2007 conversion. -

Downtown Pittsburgh Retail Market Analysis MJB Consulting / July 2008

Downtown Pittsburgh Retail Market Analysis MJB Consulting / July 2008 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Downtown Pittsburgh Retail Market Analysis Undertaken On Behalf Of The Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership MJB Consulting July 2008 1 Downtown Pittsburgh Retail Market Analysis MJB Consulting / July 2008 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Table of Contents Chapter Page Acknowledgments 3 Executive Summary 4 Illustrative Map 16 Introduction 17 Chapter 1: Worker-Driven Retail 19 Chapter 2: Resident-Driven Retail 35 Chapter 3: Event-Driven Retail & The Dining/Nightlife Scene 50 Chapter 4: Student-Driven Retail 72 Chapter 5: Destination Retail 82 2 Downtown Pittsburgh Retail Market Analysis MJB Consulting / July 2008 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Acknowledgments MJB Consulting and the Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership would like to thank the Heinz Foundation for its generosity in funding this study. We would also like to thank the members of the Downtown Task Force for their time and input, as well as the individuals who were willing to be interviewed, including Jared Imperatore (Grant Street Associates), Art DiDonato (GVA Oxford), Herky Pollock and Jason Cannon (CB Richard Ellis), Kevin Langholz (Langholz Wilson Ellis Inc.), Mariann Geyer (Point Park University) and Rebecca White (The Pittsburgh Cultural