Tsuinfo Alert, April 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Chaos 031606

GoNorth! Weekly Chat ~ March 16, 2006 Module 02, Week 5 with Weather Channel meteorologist Dan Dix Phusky: Welcome from Education Basecamp! Here is a quick bio on today's speaker … Please welcome our speaker! What questions do you have for Dan today? St. Paul, MN: Hello Dan! What do you do as a meteorologist? Go North! Speaker: I used to forecast the weather for aviation and other transportation lines....then more to a public audience here at the Weather Channel jolene: what do u think we could do to help global warming? Anne Chesnutt Middle School, North Carolina: Yes, what can we do to help global warming? Go North! Speaker: Obviously a change in our usage of fossil fuels -- as a world we "are addicted to oil" .. solar, wind, & other alternatives are a great start Anne Chesnutt Middle School, North Carolina 2: What is the climate like in Alaska? Go North! Speaker: Typically cold especially interior .. but along the coasts its much more like Seattle or Portland but a bit colder..more rain then snow.... Anne Chesnutt Middle School, North Carolina: What are some negative outcomes of climate change? Phusky: Can you each think of some negative outcomes? St. Paul, MN: I know that the Weather Channel is located in Atlanta, Ga. How do you then forecast to all areas of the world? Go North! Speaker: We receive weather information from around the world every hour -- sometimes more than what some local areas far away can see .. so we can make some good forecasts using satellite, hourly observations and upper air data. -

Elizabethpolice Findtaxicab Murderer Used

VOLUME 82, NO. 114 RED BANK. N. J.. WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 27, 1MQ 7c PER COPY PAGE ONI Attorney Htm Short Red Bank School —But Warm—Ride ElizabethPolice SEA BRIGHT - A. Henry Budget Adopted Lang Branch, had FindTaxicab The bereagb attoroey'e car RED BANK-A 1*041 school kM^gfe* Hm*'- halaea Bui ll budget totaling $1.S«.S1I •aaaJBH HaBJ epeJOjVSjV. eW' Shepard adopted last night by the Board get a mac Murderer Used of Education after a public hear- cd.oa* tram ig. - • The 47-mlnute bearing went The whtatto Four Killed Criticizessmoothly, with residents question- and tin Robber Ing only a few Items. On North After the budget had beta Jo ahnda te gat at the twvwwvo* ifUBfBjvvrr ruwwwi *»* Officials Lewis, Ml Spring St. said he tnaato. I'taaBy, the Of Bank Jersey Estate felt the board hu been "dicta- "Winder what NEW, SHREWSBURY - the torial" in its handling of teach- Mr. NORTH BRUNSWICK basic attitude of members of this ers. when I fteaae* to sat kame AP)-Pollce today found borough's governing bodies mutt early, toe. What a way tar aAt Large abandoned in Elizabeth tht chinge if the town U to aolvo id Board member Or. Herman 0. aww car to aet as." tax problem! by attractiiii rat* Wiley men charged Mr. Lewis __a^ cv^ gUjjjfjO^ggl fno^kW FARMINGDALE-The March red-and-black Uudcab used bin, Tax Assessor Andrew G. with hiving a "belligerent" at- be got te» tbe car atfor the Maaaaquan man wiped- for flight by the murder*? Snepard told a meeting of tbe titude at board meetings. -

US Mainstream Media Index May 2021.Pdf

Mainstream Media Top Investors/Donors/Owners Ownership Type Medium Reach # estimated monthly (ranked by audience size) for ranking purposes 1 Wikipedia Google was the biggest funder in 2020 Non Profit Digital Only In July 2020, there were 1,700,000,000 along with Wojcicki Foundation 5B visitors to Wikipedia. (YouTube) Foundation while the largest BBC reports, via donor to its endowment is Arcadia, a Wikipedia, that the site charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and had on average in 2020, Peter Baldwin. Other major donors 1.7 billion unique visitors include Google.org, Amazon, Musk every month. SimilarWeb Foundation, George Soros, Craig reports over 5B monthly Newmark, Facebook and the late Jim visits for April 2021. Pacha. Wikipedia spends $55M/year on salaries and programs with a total of $112M in expenses in 2020 while all content is user-generated (free). 2 FOX Rupert Murdoch has a controlling Publicly Traded TV/digital site 2.6M in Jan. 2021. 3.6 833,000,000 interest in News Corp. million households – Average weekday prime Rupert Murdoch Executive Chairman, time news audience in News Corp, son Lachlan K. Murdoch, Co- 2020. Website visits in Chairman, News Corp, Executive Dec. 2020: FOX 332M. Chairman & Chief Executive Officer, Fox Source: Adweek and Corporation, Executive Chairman, NOVA Press Gazette. However, Entertainment Group. Fox News is owned unique monthly views by the Fox Corporation, which is owned in are 113M in Dec. 2020. part by the Murdoch Family (39% share). It’s also important to point out that the same person with Fox News ownership, Rupert Murdoch, owns News Corp with the same 39% share, and News Corp owns the New York Post, HarperCollins, and the Wall Street Journal. -

Michel Chossudovsky America’S “War on Terrorism”

SECOND EDITION MICHEL CHOSSUDOVSKY AMERICA’S “WAR ON TERRORISM” Global Research America’s “War on Terrorism” Michel Chossudovsky “Material this provocative and well researched must not be ignored.” Scott Loughrey, The Baltimore Chronicle “Chossudovsky’s book presents its readers with a harsh reality: ter- rorism is a tool used to maintain and expand the growth of cor- porate capitalism, led by the U.S. dollar and backed by U.S. military might. His book is one of those ‘connect-the-dots’ works that should be required reading, especially for media-misled, history-starved Americans.” Kellia Ramares, Online Journal “Canadian professor of economics Michel Chossudovsky contains that rare gift of a writer who can compile massive documentary evidence, then propound it in a succinct, lucid manner. His book cuts through the morass of Bush verbiage, daring readers to examine the pure, unvarnished truth of a nation using its military and intel- ligence capabilities to control the global oil market on the pretext of America’s making the world a safer place.” William Hare, Amazon.com “War on Terrorism” “Chossudovsky has written an alarming book that ought to serve as a wakeup call for every citizen of the world. In a very straight- Second Edition forward manner, Chossudovsky uncovers the truth behind America’s covert intelligence operations, international economic interests, and goals of US foreign policy.” Anthony Lafratta, Chapters-Indigo. Global Research To the Memory of André Gunder Frank America’s “War on Terrorism”, by Michel Chossudovsky — Second Edition. © Michel Chossudovsky, 2005. All rights reserved – Global Research, Center for Research on Globalization (CRG). -

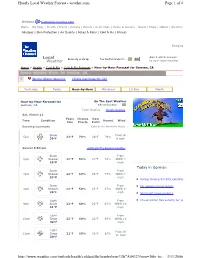

Local Weather Page 1 of 4 Hourly Local Weather Forcast

Hourly Local Weather Forcast - weather.com Page 1 of 4 Welcome. Customize weather.com Home My Page | Health | Travel | Driving | Events | Recreation | Home & Garden World | Maps | Mobile | Weather Allergies | Skin Protection | Air Quality | Aches & Pains | Cold & Flu | Fitness Bringing Get 1-click access Local Enter city or US zip See weather related to ... Weather to your local weather Home > Health > Cold & Flu > Cold & Flu Forecast > Hour-by-Hour Forecast for Gorman, CA Winter Storm Warning [State warnings for CA] Yesterday Today Hour-by-Hour Weekend 10-Day Month Hour-by-Hour Forecast for On The Spot Weather Gorman, CA Choose Location Table Display Graph Display Sat, March 11 Feels Chance Dew Time Condition Humid. Wind Like Precip Point Evening Commute Cold & Flu Weather Maps Snow From W 5pm 24°F 70% 28°F 79% 30°F 6 mph Sunset 5:59 pm 2005-06 Flu Season Update Snow From 6pm Shower 22°F 50% 27°F 74% WNW 7 29°F mph Today in Gorman Snow From 7pm Shower 22°F 50% 26°F 74% WNW 7 29°F mph z Winter driving & traffic conditio Snow From z Flu season status report 8pm Shower 22°F 50% 25°F 67% WNW 9 30°F mph z Ski resort snow updates Light From z Check winter flea activity for yo 9pm Snow 22°F 60% 23°F 67% WNW 10 31°F mph Light From 10pm Snow 23°F 60% 22°F 64% WNW 12 32°F mph Light From W 11pm Snow 21°F 60% 22°F 63% 11 mph 30°F http://www.weather.com/outlook/health/coldandflu/hourbyhour/USCA0432?from=36hr_to.. -

Vitae E V E G R U N T F E S T June 2018

Curriculum Vitae E V E G R U N T F E S T http://www.EveGruntfest.com June 2018 633 Ramona Avenue Space 126 Los Osos, CA 93402 voice: 719 551 0407 email: [email protected] ACADEMIC TRAINING • Ph.D. Geography University of Colorado at Boulder, CO 1982 • M.A. Geography University of Colorado at Boulder, CO 1977 • B.A. Geography Clark University Worcester, MA 1973 ACADEMIC WORK EXPERIENCE 02/16- 8/17 Professional Research Associate Resilient Communities Research Institute Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo, CA 10/12-10/13 Program Director Geosciences Directorate, Atmospheric & Geospace Sciences, Nation Science Foundation, Arlington, VA 5/08-5/12 Director Social Science Woven into Meteorology (SSWIM) Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies (CIMMS) & the U of Oklahoma at National Weather Center Norman, OK 12/08- Adjunct Faculty Department of Geography & Environmental Sustainability, U of Oklahoma Norman, OK 2/10-7/10 Visiting Scientist Laboratoire d'étude des Transferts en Hydrologie et Environnement & Geography Department Joseph Fourier U Grenoble, France 9/09-9/10 Co-Director International Flash Flood Laboratory, Texas State U San Marcos, TX 12/07- Professor Emeritus Geography & Environmental Studies, U of Colorado at Colorado Springs, CO 6/00-12/07Professor Geography & Environmental Studies, U of Colorado at Colorado Springs, CO 6/05-9/06 Visiting Scientist National Center for Atmospheric Research Boulder, CO 3/03-6/03 Distinguished Chair of Geography U of Trieste, Italy, Fulbright scholarship 8/98 - 6/99Department Chair Geography -

Department of Geography Texas State University-San Marcos

DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY TEXAS STATE UNIVERSITY-SAN MARCOS ACADEMIC PROGRAM REVIEW SELF-STUDY REPORT 2001-2007 April 2008 Academic Program Review Self-Study Report Committee Dr. Philip W. Suckling, Professor and Chair (Committee Co-Chair) Mr. Mark Carter, Senior Lecturer (Committee Co-Chair) Dr. David Butler, Professor and Graduate Coordinator Dr. Alberto Giordano, Associate Professor Dr. William DeSoto, Associate Professor of Political Science Ms. Allison Glass, Coordinator of Department Recruiting Ms. Johanna Ostling, Ph.D. student Ms. Monica Mason, Master’s student and 2007 B.S. alumna Assisted by: Ms. Angelika Wahl, Senior Administrative Assistant TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. ACADEMIC UNIT DESCRIPTION 1 II. DEGREE AND CERTIFICATE PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS 3 III. INSTITUTIONAL DATA 13 IV. STUDENTS 19 V. FACULTY 25 VI. RESOURCES 28 VII. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 33 1 I. ACADEMIC UNIT DESCRIPTION A. List the degree and certificate programs offered by the academic unit Undergraduate Majors: B.A. or B.S. in Geography (general) B.S. in Geography (with teacher certification) B.S. in Geography – Resource and Environmental Studies B.S. in Geography – Geographic Information Science B.S. in Geography – Urban and Regional Planning B.S. in Geography – Physical Geography B.S. in Geography – Water Studies Graduate Majors: M.A.Geo (Master of Applied Geography) in Geography M.A.Geo in Geography – Resource and Environmental Studies M.A.Geo in Geography – Geographic Information Science M.A.Geo in Geography – Land/Area Development and Management M.S. in Geography Ph.D. in Geography – Environmental Geography Ph.D. in Geography – Geographic Education Ph.D. in Geography – Geographic Information Science Undergraduate Minors: minor in Geography minor in Nature and Heritage Tourism minor in Geology (departmental responsibility effective Fall 2008) Certificates: Certificate in Geographic Information Systems Certificate in Water Resources Policy B. -

Grace Atkins Sound Mixer Resume 2013

Gracie Atkins Sound Mixer and Producer Resume Honolulu, Hawaii USA 808-395-6662/ 808-341-6662 /[email protected] Theatrical and Independent Shorts: Sound Mixer “To the Wonder” Terrence Malick - Director 35mm. 2nd unit Redbud Pictures Tyrannausaurus Azteca. 35mm feature. Rigel Entertainment, Sci-Fi Channel Heat Stroke. Sound Mixer. 35mm feature. Rigel Entertainment, Sci Fi Channel Chief. Sound Mixer. Super 16mm short feature. RedHead Productions 2008 Sundance Film Festival official short film selection. Tides of War. 2-camera HD feature film. Regent Entertainment LA. Silent Years. BAFTA nominated short. Super-16mm. Kinetic The Land Has Eyes. Sound Mixer for super-16mm/video feature. TeMaka Productions, Inc. 2003 Sundance Film Festival- Native Forum. Dolphins. IMAX. Sound Mixer. Location producer Argentina.. MacGillivray-Freeman Films Academy Award nominated film 2002. PRODUCER/SOUND MIXER: One-Hour Documentary Specials; Secret Killers of Monterey Bay (National Geographic Television Special, co-production with BBC. 2001/2002.) Narrated by Edward Norton. Cine Golden Eagle Jury Award and Cine Masters Series Award 2003. Dolphins: The Wild Side (National Geographic Special - NBC/BBC, 1999) Cine Golden Eagle, 1999; Jackson Wildlife Film Festival: Best Animal Behavior, 1999 NY Film Festival, World Silver, 1999, Directing Nomination, News and Documentary Emmy, 2000. Great White Shark (National Geographic Special - BBC/NBC; 1995). Emmy: Cinematography, 1996 Hawaii: Strangers in Paradise (National Geographic Special/PBS; 1991). Narrated by F. Murray Abraham. Nominated for 4 Emmies: Cinematography, Directing, Sound and Best Information and Cultural Programming. Received 2 Emmies, Sound and Best IC Programing. Nautilus: 500 Million Years Under the Sea (Moana/Film Crew/PBS; 1987). Cine Golden Eagle, Gold - NY Film Fest, other awards. -

Seattle Fault Earthquake Scenario Project

2008 National Awards in Excellence Outreach Seattle Fault Earthquake Scenario Project Washington Military Department, Emergency Management Division (EMD) and Earthquake Engineering Research Institute Mark Stewart, State Hazard Mitigation Programs Manager, Washington EMD Building 20, M/S: 20, Camp Murray Washington 98430-5122 [email protected] Tel: 253-512-7067 Fax: 253-512-7072 Susan Tubbesing, Executive Director, Earthquake Engineering Research Institute th 499 14 Street Suite 320, Oakland, CA 94612-1934 [email protected] Tel: 510-451-0905 Fax: 510-451-5411 The Seattle Fault Earthquake Scenario project began in 2002 when public and private sector experts in the Central Puget Sound region of Washington State grew increasingly concerned in recent years about earthquake safety as they learned more about region’s earthquake threat. A 12-member multi-disciplinary project team of scientists, engineers, planners, emergency managers, and social scientists used recent geologic findings, other current research, and knowledge of land-use and development trends to forecast the impact of a scenario earthquake in the heavily populated region. The Scenario for a Magnitude 6.7 Earthquake on the Seattle Fault publication which resulted also made high-level recommendations to decision makers on improving earthquake safety. The target audiences of this project included local and state decision makers, public and private sector emergency managers, local land-use planners, engineers, and architects. The Seattle Fault Earthquake Scenario Project Team unveiled its findings to public officials in the study area in early February 2005. The project was featured in a front page feature in the February 20, 2005 Sunday Seattle Times, and presented to a conference attended by nearly 500 individuals on the fourth anniversary of the 2001 Nisqually Earthquake Disaster, February 28, 2005. -

May 3, 2012 Public Meeting Transcript

Canadian Nuclear Commission canadienne de Safety Commission sûreté nucléaire Public meeting Réunion publique May 3rd, 2012 Le 3 mai 2012 Public Hearing Room Salle d’audiences publiques 14th floor 14e étage 280 Slater Street 280, rue Slater Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa (Ontario) Commission Members present Commissaires présents Dr. Michael Binder M. Michael Binder Dr. Moyra McDill Mme Moyra McDill Mr. Dan Tolgyesi M. Dan Tolgyesi Ms. Rumina Velshi Mme Rumina Velshi Dr. Ronald Barriault M. Ronald Barriault Mr. André Harvey M. André Harvey Secretary: Secrétaire: Mr. Marc Leblanc M. Marc Leblanc Senior General Counsel : Avocat général principal: Mr. Jacques Lavoie M. Jacques Lavoie (ii) TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Opening Remarks 1 6. Status Report 3 6.1 Status Report on Power Reactors 3 6.2 Early Notification Reports 10 6.2.1 - 12-M28 10 Ontario Power Generation Inc.: Workplace Fatality at OPG’s Darlington Nuclear Generating Station 6.2.2 - 12-M29 12 Hydro-Québec : Fuite d’eau lourde dans le bâtiment Réacteur à Gentilly-2 5. Information Items 23 5.1 Actions required by the CNSC, 23 Licensees and affected stakeholders to address the Task Force recommendations and Outcome of the public Consultation on the CNSC Fukushima Task Force Report And CNSC Management Response 12-M23 / 12-M23.B 25 Oral presentation by CNSC staff 12-M23.1 / 12-M23.1A 92 Oral presentation by the Canadian Standards Association (CSA Group) (iii) TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 12-M23.2 115 Oral presentation by Marchhurst Technologies Corporation 12-M23.5 / 12-M23.5A 135 Oral presentation by Ontario Power Generation 12-M23.12 172 Exposé oral par Hydro-Québec 12-M23.7 / 12-M23.7A 189 Oral presentation by Michel A. -

Special Weekend Edition, June 29, 2008

file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/gmargasa/Desktop/ROG_2008_0629.htm SFWMD SPECIAL WEEKEND EDITION, JUNE 29, 2008 Compiled by: South Florida Water Management District (for internal use only) Total Clips: 52 Headline Date Outlet Reporter Interest could double cost of 06/27/2008 Forbes - Online Everglades land deal Political pluck, power Palm Beach Post - dovetailed in state-U.S. 06/28/2008 Singer, Stacey Online Sugar deal Florida Keys Kevin Wadlow Senior A whole bunch of questions' 06/28/2008 Keynoter Staff Writer Gov. Crist Pact With U.S. Town-Crier Sugar 'A Gift To The 06/28/2008 Newspapers, The Everglades' Everglades of past now out St. Petersburg 06/28/2008 Craig Pittman of reach? Times - Online CURTIS MORGAN Sugar deal won't let water Miami Herald - 06/29/2008 AND SCOTT flow Online HIAASEN Plan to restore flow from Palm Beach Post - Lake O revives arguments 06/28/2008 Kleinberg, Eliot Online from '93 JENNIFER Buyout called largest Palm Beach Post - 06/28/2008 SORENTRUE and finance deal of its kind Online ELIOT KLEINBERG A sweet deal? Region's environment could benefit 06/28/2008 Naples Daily News Staats, Eric from U.S. Sugar buyout Sugar deal financing plan 06/29/2008 TMCnet.com pushes land cost higher file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/gmargasa/Desktop/ROG_2008_0629.htm (1 of 68) [9/4/2008 3:20:28 PM] file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/gmargasa/Desktop/ROG_2008_0629.htm Environmentalists want a South Florida Sun- more-natural Everglades 06/29/2008 Fleshler, David Sentinel - Online plan Oceanographer From Philly Explains -

It Could Happen Tomorrow by Gary Frazier

It Could Happen Tomorrow By Gary Frazier READ ONLINE If you are searching for a book by Gary Frazier It Could Happen Tomorrow in pdf format, in that case you come on to the correct website. We presented complete variant of this ebook in doc, ePub, txt, DjVu, PDF formats. You may read by Gary Frazier online It Could Happen Tomorrow or download. Besides, on our site you may read manuals and different art books online, either load them as well. We wish to attract your note what our site does not store the eBook itself, but we give ref to the website wherever you may downloading either reading online. So if want to load pdf by Gary Frazier It Could Happen Tomorrow , then you've come to the faithful site. We have It Could Happen Tomorrow txt, ePub, PDF, DjVu, doc formats. We will be pleased if you revert us more. Kncsb: lending library » it could happen tomorrow – dvd & cd This kit contains eight 30-minute video lessons. This study is an encouraging affirmation and comfort to Christians, yet it is also an urgent sobering call to It could happen tomorrow - veryparanormal A compelling documentary exploring the subject of Extraterrestrial Presence and the disclosure movement Vcy america - it could happen tomorrow part 2 He joined Jim to present a second hour of discussion concerning the Bible's prophetic time-line from the book, 'It Could Happen Tomorrow: It could happen tomorrow by gary frazier - vcy crosstalk america Our current world events indicate that Old and New Testament prophecies are being fulfilled.