“IT FLOWS THROUGH ME LIKE RAIN” Christof Decker Minimalism in Film Scoring May Seem Like a Contradiction in Terms. When Holl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Dead Zone Back to the Beach I Scored! the 250 Greatest

Volume 10, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies and Television FAN MADE MONSTER! Elfman Goes Wonky Exclusive interview on Charlie and Corpse Bride, too! Dead Zone Klimek and Heil meet Romero Back to the Beach John Williams’ Jaws at 30 I Scored! Confessions of a fi rst-time fi lm composer The 250 Greatest AFI’s Film Score Nominees New Feature: Composer’s Corner PLUS: Dozens of CD & DVD Reviews $7.95 U.S. • $8.95 Canada �������������������������������������������� ����������������������� ���������������������� contents ���������������������� �������� ����� ��������� �������� ������ ���� ���������������������������� ������������������������� ��������������� �������������������������������������������������� ����� ��� ��������� ����������� ���� ������������ ������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������� ��������������������� �������������������� ���������������������������������������������� ����������� ����������� ���������� �������� ������������������������������� ���������������������������������� ������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������ ��������������������������������������� ������������������������������� �������������������������� ���������� ���������������������������� ��������������������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������� �������������������������������������������� ������������������������������ �������������������������� -

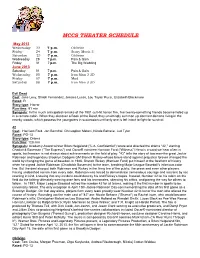

Mccs Theater Schedule

MCCS THEATER SCHEDULE May 2013 Wednesday 22 7 p.m. Oblivion Friday 24 7 p.m. Scary Movie 5 Saturday 25 7 p.m. Oblivion Wednesday 29 7 p.m. Pain & Gain Friday 31 7 p.m. The Big Wedding June 2013 Saturday 01 7 p.m. Pain & Gain Wednesday 05 7 p.m. Iron Man 3 3D Friday 07 7 p.m. Mud Saturday 08 7 p.m. Iron Man 3 3D Evil Dead Cast: Jane Levy, Shiloh Fernandez, Jessica Lucas, Lou Taylor Pucci, Elizabeth Blackmore Rated: R Story type: Horror Run time: 91 min Synopsis: In the much anticipated remake of the 1981 cult-hit horror film, five twenty-something friends become holed up in a remote cabin. When they discover a Book of the Dead, they unwittingly summon up dormant demons living in the nearby woods, which possess the youngsters in succession until only one is left intact to fight for survival. 42 Cast: Harrison Ford, Jon Bernthal, Christopher Meloni, Nicole Beharie, Jud Tylor Rated: PG-13 Story type: Drama Run time: 128 min Synopsis: Academy Award winner Brian Helgeland ("L.A. Confidential") wrote and directed the drama "42," starring Chadwick Boseman ("The Express") and OscarR nominee Harrison Ford ("Witness").Hero is a word we hear often in sports, but heroism is not always about achievements on the field of play. "42" tells the story of two men-the great Jackie Robinson and legendary Brooklyn Dodgers GM Branch Rickey-whose brave stand against prejudice forever changed the world by changing the game of baseball. In 1946, Branch Rickey (Harrison Ford) put himself at the forefront of history when he signed Jackie Robinson (Chadwick Boseman) to the team, breaking Major League Baseball's infamous color line. -

Allusion As a Cinematic Device

I’VE SEEN THIS ALL BEFORE: ALLUSION AS A CINEMATIC DEVICE by BRYCE EMANUEL THOMPSON A THESIS Presented to the Department of Cinema Studies and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2019 An Abstract of the Thesis of Bryce Thompson for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Cinema Studies to be taken June 2019 Title: I’ve Seen this All Before: Allusion as a Cinematic Device Approved: _______________________________________ Daniel Gómez Steinhart Scholarship concerning allusion as a cinematic device is practically non- existent, however, the prevalence of the device within the medium is quite abundant. In light of this, this study seeks to understand allusion on its own terms, exploring its adaptation to cinema. Through a survey of the effective qualities of allusion, a taxonomy of allusionary types, film theory, and allusion’s application in independent cinema, it is apparent that allusion excels within the cinematic form and demonstrates the great versatility and maximalist nature of the discipline. With the groundwork laid out by this study, hopefully further scholarship will develop on the topic of allusion in order to properly understand such a pervasive and complex tool. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my thesis committee of Professor Daniel Steinhart, Professor Casey Shoop, and Professor Allison McGuffie for their continued support, mentorship, and patience. I would also like to thank Professor Louise Bishop who has been immensely helpful in my time at university and in my research. I have only the most overwhelming gratitude towards these gracious teachers who were willing to guide me through this strenuous but rewarding process, as I explore the maddening and inexact world of allusion. -

CO 52.03 Hallas.Cs

Still from Decodings (dir. Michael Wallin, US, 1988) AIDS and Gay Cinephilia Roger Hallas In Positiv, the opening short film in Mike Hoolboom’s six-part compilation film Panic Bodies (Canada, 1998), the viewer is faced with a veritable excess of the visual. The screen is divided into four equal parts, suggesting both a wall of video monitors and also Warhol’s famed simultaneous projections. Hoolboom, a Toronto-based experimental filmmaker who has been HIV posi- tive since 1988, appears in the top right-hand frame as a talking head, tightly framed and speaking directly to the camera. At once poignant and wry, his monologue explores the corporeal experi- ence of living with AIDS: “The yeast in my mouth is so bad it turns all my favorite foods, even chocolate-chocolate-chip ice cream, into a dull metallic taste like licking a crowbar. I know then that my body, my real body, is somewhere else: bungee jumping into mine shafts stuffed with chocolate wafers and whipped cream and blueberry pie and just having a good time. You know?” Each of the other three frames is filled with a montage of images from contemporary Hollywood films, B-movies, vintage porn, home movies, ephemeral films, as well as Hoolboom’s own experimen- tal films. These multiple frames feed the viewer a plethora of diverse visual sensations. They include disintegrating and morphing Copyright © 2003 by Camera Obscura Camera Obscura 52, Volume 18, Number 1 Published by Duke University Press 85 86 • Camera Obscura bodies (from The Hunger [dir. Tony Scott, UK, 1983], Terminator 2 [dir. -

0 Musical Borrowing in Hip-Hop

MUSICAL BORROWING IN HIP-HOP MUSIC: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS AND CASE STUDIES Justin A. Williams, BA, MMus Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2009 0 Musical Borrowing in Hip-hop Music: Theoretical Frameworks and Case Studies Justin A. Williams ABSTRACT ‗Musical Borrowing in Hip-hop‘ begins with a crucial premise: the hip-hop world, as an imagined community, regards unconcealed intertextuality as integral to the production and reception of its artistic culture. In other words, borrowing, in its multidimensional forms and manifestations, is central to the aesthetics of hip-hop. This study of borrowing in hip-hop music, which transcends narrow discourses on ‗sampling‘ (digital sampling), illustrates the variety of ways that one can borrow from a source text or trope, and ways that audiences identify and respond to these practices. Another function of this thesis is to initiate a more nuanced discourse in hip-hop studies, to allow for the number of intertextual avenues travelled within hip-hop recordings, and to present academic frameworks with which to study them. The following five chapters provide case studies that prove that musical borrowing, part and parcel of hip-hop aesthetics, occurs on multiple planes and within myriad dimensions. These case studies include borrowing from the internal past of the genre (Ch. 1), the use of jazz and its reception as an ‗art music‘ within hip-hop (Ch. 2), borrowing and mixing intended for listening spaces such as the automobile (Ch. 3), sampling the voice of rap artists posthumously (Ch. 4), and sampling and borrowing as lineage within the gangsta rap subgenre (Ch. -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

Download the Digital Booklet

CD1 Star Wars: A New Hope: 01. Star Wars: A New Hope 02. Cantina Band 03. Princess Leia 04. The Throne Room / Finale Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back: 05. The Imperial March 06. Han Solo and The Princess 07. The Asteroid Field 08. Yoda's Theme Star Wars: Return Of The Jedi: 09. Forest Battle Star Wars: The Phantom Menace: 10. Anakin's Theme 11. The Flag Parade 12. The Adventures Of Jar Jar 13. Duel Of The Fates Star Wars: Attack Of The Clones: 14. Across The Stars STAR WARS STAR Star Wars: Revenge Of The Sith: 15. Battle Of The Heroes CD2 Raiders Of The Lost Ark: 01. The Raiders March 02. The Map Room / Dawn 03. The Basket Game 04. Marion's Theme 05. Airplane Fight 06. The Ark Trek 07. Raiders Of The Lost Ark Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom: 08. Nocturnal Activities 09. The Mine Car Chase 10. Indiana Jones And The Temple Of Doom End Credits Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade: 11. Indy's First Adventure 12. X Marks The Spot / Escape From Venice 13. No Ticket / Keeping Up With The Joneses 14. Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade End Credits INDIANA JONES CD3 Harry Potter And The Philosopher's Stone: 01. Hedwig's Theme 02. Nimbus 2000 03. Harry's Wondrous World 04. Christmas at Hogwarts 05. Leaving Hogwarts Harry Potter And The Chamber Of Secrets: 06. Fawkes The Phoenix 07. The Chamber of Secrets 08. Gilderoy Lockhart 09. Dobby the House Elf 10. Reunion of Friends Harry Potter And The Prisoner of Azkaban: 11. -

Goldsmith 1929-2004

Volume 9, Number 7 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies and Television Goodbye, David pg. 4 JERRY GOLDSMITH 1929-2004 07> 7225274 93704 $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada v9n07COV.id 1 9/7/04, 3:36:04 PM v9n07COV.id 2 9/7/04, 3:36:07 PM contents AUGUST 2004 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial Jerry Goldsmith 1929-2004 Let the Healing Begin. It would be difficult to reflect on both Jerry Goldsmith’s film music legacy and his recent passing without devoting an entire 4 News issue of FSM to him; so that’s what we’ve done. From fan Goodbye, David. letters and remembrances to an in-depth look at his life and 5 Record Label musical legacy, we’ve covered a lot of ground. Just as impor- Round-up tant, we hope you, Jerry’s fans, find it a fitting tribute to a man What’s on the way. whose monumental work meant so much to so many. 5 Now Playing Movies and CDs in The Artist, release. 12 The Gold Standard 6 Concerts Quantifying Jerry Goldsmith’s contribution to film scoring Film music performed isn’t easy...but we’ll try anyway. around the globe. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 19 Goldsmith Without Tears Who’s writing what The imagined, decades-long conversation with Goldsmith for whom. may be over, but his music lives on. By John S. Walsh 9 Mail Bag Lonely Are the Brave. 24 Islands in the Stream 10 Pukas Jerry’s industry contemporaries chime in on If Only It Were True. -

John Patitucci Biography

Three Faces Management John Patitucci Biography John Patitucci was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1959 and began playing the electric bass at age ten. He began performing and composing at age 12, at age 15 began to play the acoustic bass, and then started the piano at age 16. He quickly moved from playing soul and rock to blues, jazz and classical music. His eclectic tastes caused him to explore all types of music as a player and a composer. John studied classical bass at San Francisco State University and Long Beach State Uni- versity. In 1980, he continued his career in Los Angeles as a studio musician and a jazz artist. As a studio musician, John has played on countless albums with artists such as B. B. King, Bonnie Raitt, Chick Corea, Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Michael Brecker, George Benson, Dizzy Gillespie, Was Not Was, Dave Grusin, Natalie Cole, Bon Jovi, Sting, Queen Latifah and Carly Simon. In 1986, John was voted by his peers in the studios as the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences MVP on Acoustic Bass. As a performer, John has played throughout the world with his own band and with jazz luminaries Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter, Stan Getz, Pat Metheny, Wynton Marsalis, Joshua Redman, Michael Brecker, McCoy Tyner, Nancy Wilson, Randy Brecker, Fred- die Hubbard, Tony Williams, Hubert Laws, Hank Jones, Mulgrew Miller, James Williams, Kenny Werner and scores of others. Some of the many pop and Brazilian artists he has played with include Sting, Aaron Neville, Natalie Cole, Joni Mitchell, Carole King, Milton Nascimien- to, Astrud and Joao Gilberto, Airto and Flora Purim, Ivan Lins, Joao Bosco and Dori Caymmi. -

John Barry Aaron Copland Mark Snow, John Ottman & Harry Gregson

Volume 10, Number 3 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies and Television HOLY CATS! pg. 24 The Circle Is Complete John Williams wraps up the saga that started it all John Barry Psyched out in the 1970s Aaron Copland Betrayed by Hollywood? Mark Snow, John Ottman & Harry Gregson-Williams Discuss their latest projects Are80% You1.5 BWR P Da Nerd? Take FSM’s fi rst soundtrack quiz! �� � ����� ����� � $7.95 U.S. • $8.95 Canada ������������������������������������������� May/June 2005 ����������������������������������������� contents �������������� �������� ������� ��������� ������������� ����������� ������� �������������� ��������������� ���������� ���������� �������� ��������� ����������������� ��������� ����������������� ���������������������� ������������������������������ �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������� ������������������������������������������������������ ����������������������������������������������������������������������� FILM SCORE MAGAZINE 3 MAY/JUNE 2005 contents May/June 2005 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 4 Editorial 31 The Circle Is Complete Much Ado About Summer. Nearly 30 years after -

Book Reviews – October 2011

Scope: An Online Journal of Film and Television Studies Issue 21 October 2011 Book Reviews – October 2011 Table of Contents History by Hollywood By Robert Brent Toplin Cinema Wars: Hollywood Film and Politics in the Bush-Cheney Era By Douglas Kellner Cinematic Geopolitics By Michael J. Shapiro A Review by Brian Faucette ................................................................... 4 What Cinema Is! By Dudley Andrew The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film By Laura Rascaroli A Review by Daniele Rugo ................................................................... 12 All about Almodóvar: A Passion for Cinema Edited by Brad Epps and Despina Kakoudaki Stephen King on the Big Screen By Mark Browning A Review by Edmund P. Cueva ............................................................. 17 Crisis and Capitalism in Contemporary Argentine Cinema By Joanna Page Writing National Cinema: Film Journals and Film Culture in Peru By Jeffrey Middents Latsploitation, Exploitation Cinemas, and Latin America Edited by Victoria Ruétalo and Dolores Tierney A Review by Rowena Santos Aquino ...................................................... 22 Film Theory and Contemporary Hollywood Movies 1 Book Reviews Edited by Warren Buckland Post-Classical Hollywood: Film Industry, Style and Ideology Since 1945 By Barry Langford Hollywood Blockbusters: The Anthropology of Popular Movies By David Sutton and Peter Wogan A Review by Steen Christiansen ........................................................... 28 The British Cinema Book Edited