Bmcgowan (8.607Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regent Street Leeds LS2 7UZ

FOR SALE – BUILD READY NEW BUILD RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY Fully Consented Scheme Regent Street Leeds LS2 7UZ • Site of approx. 0.52 acres (0.21 ha) • Full planning permission for 217 Apartments with ancillary residents lounge, gym space, communal garden, roof terrace and cinema room • Located in the heart of mixed use MABGATE redevelopment area, 5 mins walk from John Lewis and Leeds City Centre • Highly accessible location close to Inner Ring Road and Motorway network. Strategic Property & Asset Solutions CGI www.fljltd.co.uk Location: The subject site is situated on the edge of Leeds City Centre. Just north of the Leeds Inner Ring Road (A58/A64) . Leeds is the third largest city in the UK, with the Leeds City Region having a population of approximately 3 mil- lion. The Leeds City Region has nine Higher Education facilities including Leeds University and Leeds Beckett University, with a total of over 120,000 students studying in the city. The site is within comfortable walking dis- tance of the Leeds Becketts and Leeds University campuses Leeds is now in the top three retail destinations in the UK outside of London following Land Securities’ £350m Trinity Leeds, which opened in spring 2013 and Hammerson’s £650m Victoria Gate which opened in Winter 2016. Leeds benefits from excellent communications via the M621 which serves the city and links with the intersection of the M1 and M62 motorways 7 miles to the south and the A1(M) 10 miles to the east thereafter. Situation: The subject property is located 0.5 miles to the north east of Leeds City Centre. -

Leeds Integrated Station Masterplan and Leeds City Region HS2 Growth Strategy

Report author: Angela Barnicle/ Lee Arnell / Gareth Read Tel: 0113 378 7745 Report of the Director of City Development Report to Executive Board Date: 18th October 2017 Subject: Leeds Integrated Station Masterplan and Leeds City Region HS2 Growth Strategy Are specific electoral Wards affected? Yes No If relevant, name(s) of Ward(s): All Are there implications for equality and diversity and cohesion and Yes No integration? Is the decision eligible for Call-In? Yes No Does the report contain confidential or exempt information? Yes No If relevant, Access to Information Procedure Rule number: Appendix number: Summary of main issues 1. High Speed Two (HS2) has the potential to transform the economy of Leeds and Leeds City Region. However we will not realise the full benefits of HS2 unless we have a coherent and proactive plan for doing so. HS2 is part of a coherent strategy for rail improvements for the Leeds City Region, which includes upgrades of existing routes and services, and Northern Powerhouse Rail, a new fast east-west rail route across the North. 2. Improving and expanding Leeds Station is essential to ensure HS2 is integrated seamlessly with other rail services to create new rail capacity to support growth in Leeds, and to provide a high quality gateway to, and catalyst for, regeneration in the city. This paper seeks approval to the emerging proposals for a long term masterplan for Leeds Station. 3. It will also be important to ensure Leeds City Centre, and our people and businesses are HS2 ready. This paper also seeks approval -

![River Moy Map and Guide [.Pdf, 1.5MB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9040/river-moy-map-and-guide-pdf-1-5mb-459040.webp)

River Moy Map and Guide [.Pdf, 1.5MB]

Ballina Salmon Capital of Ireland Your guide to the River Moy including: Guides, Ghillies & Tackle Shops Places to Stay, Eat & Drink Useful Contacts North Western Regional Fisheries Board Bord Iascaig Réigiúnach an Iarthuaiscirt CIty of Derry Getting here: Donegal ListiNgs Belfast International Belfast City tACKLE sHOPs Jim Murray Greenhill B&B Dillons Bar & Restaurant AIR :: North Mayo is served by ireland West Airport Knock Sligo Ballina Angling Centre 33 Nephin View Manor, Foxford, Cathedral Close, Ballina, Co Mayo Dillon terrace, Ballina, Co Mayo North Mayo Unit 55, Ridge Pool Road, Ballina, Co Mayo tel: +353 (0)96 22767 tel: +353 (0)96 72230 tel: +353 (0)94 9257099 with numerous flights to Britain (www.irelandwestairport.com). Co Mayo The Loft Bar B&B Jimmy’s tel: +353 (0)96 21850 Judd Ruane Other regional Airports close by include sligo Airport, Ireland West Knock Pearse street, Ballina, Co Mayo Clare street, Ballina, Co Mayo Email: [email protected] Dublin Nephin View, the Quay, Ballina, tel:+353 (0)96 21881 tel: +353 (0)96 22617 (www.sligoairport.com) and galway Airport, PJ Tiernan Co Mayo tel: +353 (0)96 22183 Galway Red River Lodge The Junction Restaurant & Take Foxford, Co Mayo Kenny Sloan Away (www.galwayairport.com) both serving UK destinations. iceford, Quay Road, Ballina, Co Mayo tel: +353 (0)94 9256731 7 Riverside, Foxford, Co Mayo tel: +353 (0)96 22841 tone street, Ballina, Co Mayo Shannon Fax: +353 (0)94 56731 tel: +353 (0)94 9256501 tel: +353 (0)96 22149 ROAD :: Ballina and north Mayo is linked to Dublin and the Email: [email protected] Suncroft B&B John Sheridan The Loft-Late Bar Web: www.themoy.comJohn 3 Cathedral Close, Ballina, Co Mayo east coast by the N5 and then the N26 from swinford. -

Leeds Brexit Impact Assessment , Item 29. PDF 4 MB

Leeds Brexit Impact Assessment Final Report May 2019 Table of Contents Report Contents Summary of Assessment 3 1. Introduction 6 2. Latest Brexit Context 9 3. Current Strategic & Economic Position of Leeds 16 4. Impact of Brexit on Trade 24 5. Impact of Brexit on Regulation 38 6. Impact of Brexit on Investment 45 7. Impact of Brexit on Migration 55 8. Impact of Brexit on People & Places 63 9. Overall Assessment of the Impact of Brexit 67 Appendix 74 Headlines 3 Summary of Assessment The UK’s exit from the EU marks a significant step-change in the country’s economic relationship with the bloc. The UK is moving Ongoing Risks of Uncertainty away from close integration and co-operation with its nearest Until there is more clarity over the UK’s future relationship with the neighbours and trading partners, towards a yet unknown EU, there remains uncertainty within the Leeds economy. This has destination which is expected to involve many more years of already reduced confidence, investment and immigration in Leeds, negotiation and uncertainty. which looks set to continue into the future. This report touches on a number of economic factors which will be The longer this period of uncertainty continues, the greater the impacted by any change in the relationship the UK has with the EU, impact this will have on the Leeds economy. Particular risks primarily around trade, regulation, investment and migration. The associated with this include: true impact will very much depend on the deal (or no deal) that the • Businesses putting off investment, harming their long-term UK makes with the EU and the success that the government has in potential and productivity. -

Mayo County Council Multi Annual Rural Water Programme 2019 - 2021

Mayo County Council Multi Annual Rural Water Programme 2019 - 2021 Scheme Name Measure Allocation Measure 1 - Source Protection of Existing Group Water Schemes Tooreen-Aughamore GWS 1 €20,000.00 Ballycroy GWS 1 €200,000.00 Glenhest GWS 1 €200,000.00 Midfield GWS 1 €20,000.00 Killaturley GWS 1 €20,000.00 Measure 2 - Public Health Compliance Killaturley GWS 2.(a) €250,000.00 Tooreen-Aughamore GWS 2.(a) €350,000.00 Kilmovee-Urlar GWS 2.(a) €110,000.00 Attymass GWS 2.(b) €510,000.00 Derryvohey GWS 2.(b) €625,000.00 Errew GWS 2.(b) €150,000.00 Funshinnagh Cross GWS 2.(b) €300,000.00 Mayo-DBO Bundle 1A GWS 2.(a) €300,000.00 Mayo-DBO Bundle No 2 GWS 2.(a) €3,000,000.00 Midfield GWS 2(a) €250,000.00 Robeen GWS 2.(b) €1,800,000.00 Cuilleens & Drimbane GWS 2.(b) €150,000.00 Measure 3 - Enhancement of existing schemes incl. Water Conservation Meelickmore GWS 3.(a) €10,160.00 Knockatubber GWS 3.(a) €76,500.00 Drum/Binghamstown GWS 3.(a) €68,000.00 Kilaturley GWS 3.(a) €187,000.00 Ellybay/Blacksod GWS 3.(a) & (b) €85,000.00 Lough Cumnel GWS 3.(a) & (b) €34,000.00 Midfield GWS 3.(a) €137,500.00 Brackloon Westport GWS 3.(a) & (b) €280,500.00 Mayo County Council Multi Annual Rural Water Programme 2019 - 2021 Scheme Name Measure Allocation MeasureMeasure 3 - Enhancement 1 - Source Protection of existing of Existingschemes Group incl. Water Water Conservation Schemes Glencorrib GWS 3.(a) & (b) €255,000.00 Callow Lake GWS 3.(a) & (b) €816,000.00 Dooyork GWS 3.(a) & (b) €148,750.00 Killasser GWS 3.(a) & (b) €578,000.00 Shraheens GWS 3.(a) & (b) €63,750.00 Tooreen-Aughamore GWS 3.(a) & (b) €170,000.00 Water Con. -

Pharmaceutical Needs Assessment

Pharmaceutical Needs Assessment 31st January 2011 PHARMACEUTICAL NEEDS ASSESSMENT Welcome . 1 1 What are pharmaceutical services? . 2 2 What is a pharmacy needs assessment? . 2 3 What is the pharmacy needs assessment for? . 3 4 Executive summary . 4 5 The Leeds population: General overview . 4 5 1. Age . 5 5 .2 Life expectancy . 5 5 .3 Ethnicity . 5 5 4. Deprivation . 5 6 Health profile of Leeds . 6 6 1. Causes of ill health . 6 6 1. 1. Alcohol . 6 6 1. .2 Drugs . 6 6 1. .3 Smoking . 7 6 1. 4. Sexual health . 7 6 1. 5. Obesity . 8 6 .2 Long term health conditions . 8 6 .2 1. Diabetes . 8 6 .2 .2 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease . 9 6 .2 .3 Coronary heart disease . 9 6 .2 4. Mental health . 9 6 .3 Mortality . 10 6 .3 1. infant mortality . 12 6 .3 .2 circulatory disease mortality . 12 6 .3 .3 cancer mortality . 12 6 .3 4. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease mortality . 13 7 Health service provision in Leeds . 13 7 1. Acute and tertiary services . 13 7 .2 Primary care services . 13 7 .3 Other primary care services . 14 7 4. NHS Leeds community healthcare services . 14 7 5. Drug and alcohol treatment services . 15 8 Current pharmaceutical provision in Leeds . 15 9 Ward summary and profiles . 22 10 Current summary of identified pharmaceutical need . 23 11 Further possible pharmaceutical services in Leeds . 86 12 Conclusions . 89 13 Acknowledgments . 89 PNA development group . x Medical director /executive sponsor . x 12 References . 90 13 Appendices . 91 14 Glossary of terms/abbreviation . -

Grinnell Thesis Submission.Pdf

Durham E-Theses Just Friendship: The Political and Societal Implications of the Practice of Relocation GRINNELL, ANDREW,DAVID How to cite: GRINNELL, ANDREW,DAVID (2019) Just Friendship: The Political and Societal Implications of the Practice of Relocation, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13155/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Just Friendship The Political and Societal Implications of the Practice of Relocation Andrew David Grinnell Doctorate of Theology and Ministry Department of Theology and Religion Durham University 1992 Just Friendship: The Political and Societal Implications of the Practice of Relocation. Andrew Grinnell Abstract: Throughout the world people motivated by their Christian faith are relocating into low- income neighbourhoods, slums and shanty towns as a response to poverty. These practitioners (I call them relocators) believe that close proximity with people who experience poverty enables missional, ecclesial and spiritual transformation. -

County Mayo Game Angling Guide

Inland Fisheries Ireland Offices IFI Ballina, IFI Galway, Ardnaree House, Teach Breac, Abbey Street, Earl’s Island, Ballina, Galway, County Mayo Co. Mayo, Ireland. River Annalee Ireland. [email protected] [email protected] Telephone: +353 (0)91 563118 Game Angling Guide Telephone: + 353 (0)96 22788 Fax: +353 (0)91 566335 Angling Guide Fax: + 353 (0)96 70543 Getting To Mayo Roads: Co. Mayo can be accessed by way of the N5 road from Dublin or the N84 from Galway. Airports: The airports in closest Belfast proximity to Mayo are Ireland West Airport Knock and Galway. Ferry Ports: Mayo can be easily accessed from Dublin and Dun Laoghaire from the South and Belfast Castlebar and Larne from the North. O/S Maps: Anglers may find the Galway Dublin Ordnance Survey Discovery Series Map No’s 22-24, 30-32 & 37-39 beneficial when visiting Co. Mayo. These are available from most newsagents and bookstores. Travel Times to Castlebar Galway 80 mins Knock 45 mins Dublin 180 mins Shannon 130 mins Belfast 240 mins Rosslare 300 mins Useful Links Angling Information: www.fishinginireland.info Travel & Accommodation: www.discoverireland.com Weather: www.met.ie Flying: www.irelandwestairport.com Ireland Maps: maps.osi.ie/publicviewer © Published by Inland Fisheries Ireland 2015. Product Code: IFI/2015/1-0451 - 006 Maps, layout & design by Shane O’Reilly. Inland Fisheries Ireland. Text by Bryan Ward, Kevin Crowley & Markus Müller. Photos Courtesy of Martin O’Grady, James Sadler, Mark Corps, Markus Müller, David Lambroughton, Rudy vanDuijnhoven & Ida Strømstad. This document includes Ordnance Survey Ireland data reproduced under OSi Copyright Permit No. -

Report of Jonathan Moxon

Report author: Ian McCall Tel: 0113 378 8012 Report of Jonathan Moxon Report to the Chief Officer (Highways and Transportation) Date: 11 February 2020 Subject: Approval for the assessment of flood management and remediation work to assets at Sheepscar Beck Are specific electoral wards affected? Yes No If yes, name(s) of ward(s): Little London & Woodhouse Has consultation been carried out? Yes No Are there implications for equality and diversity and cohesion and Yes No integration? Will the decision be open for call-in? Yes No Does the report contain confidential or exempt information? Yes No If relevant, access to information procedure rule number: Appendix number: Summary 1. Main issues Meanwood Beck (also known as Lady Beck) runs through the north of Leeds from Golden Acre Park through the city centre meeting the River Aire at Crown Point Weir. Within the city centre this watercourse is known as Sheepscar Beck and is carried by a system of large culverts and canalised open channels. The channel walls in several areas are in poor condition and have been identified to be at risk of collapse. Collapse of these walls would cause a blockage in the watercourse significantly increasing flood risk. This project is to carry out repair of the existing assets to manage the risk of these failing. This study will assess the current condition of all assets and identify the most economical option to address any issues. £60,000 funding for appraisal of a scheme has been secured through local levy funding. There is £717,000 Grant in Aid funding allocated for the design and construction phases of the project within the Environment Agency medium term plan. -

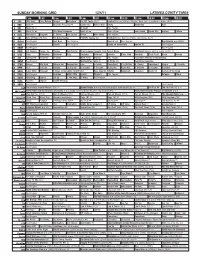

Sunday Morning Grid 12/4/11 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/4/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face/Nation Danger Horseland The NFL Today (N) Å Football Raiders at Miami Dolphins. From Sun Life Stadium in Miami. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Willa’s Wild Skiing Swimming Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour News (N) Å News (N) Å Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Explore Culture 9 KCAL Tomorrow’s Kingdom K. Shook Joel Osteen Prince Mike Webb Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Denver Broncos at Minnesota Vikings. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program Bee Season ›› (2005) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Classic Gospel Special: Tent Revival Home Prohibition Groups push to outlaw alcohol. Å 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Roadtrip Chefs Field Pépin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Al Punto (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. -

Transforming the City for Engagement

04 TRANSFORMING THE CITY FOR ENGAGEMENT DRAFT Image © Tom Joy 43 TRANSFORMING THE CITY | LEEDS OUR SPACES STRATEGY 04 4.0 APPLYING OUR PRINCIPLES Our Principles are broad and ambitious guidelines, which aim to set a course for how we will transform our spaces in years to come. This strategy also Arena considers how our principles could be applied. Civic Hall This part of the strategy illustrates how public realm across Leeds may evolve in relation to our principles and defines a number of Intervention Areas which will allow the delivery of public realm to be coherent and coordinated. Town Hall 4.1 GATEWAYS AND Bus Station LANDMARKS City Square The plan shows the city centre’s key arrival points and Corn gateways. In applying our principles to these locations Exchange we will: • create public spaces that are of a high quality, legible and accessible for pedestrians and cyclists, particularly River Aire where people arrive in the city, including around the central ‘Public Transport Box’ and around important landmark buildings; • celebrate the rich history, culture and diversity of Leeds Leeds Dock within public space to reinforce the city’s identity; • Provide comfortable and hospitable environments FOR ENGAGEMENT for people and readdress the interface between vehicle, cycle and pedestrian access. DRAFT 44 04 LEEDS OUR SPACES STRATEGY | TRANSFORMING THE CITY 4.2 A CITY ON THE MOVE The plan identifies key areas of the city centre to reconnect, including the north and south banks of the River Aire and outer edge of the city rim. In Innovation -

To Download The

4 x 2” ad EXPIRES 10/31/2021. EXPIRES 8/31/2021. Your Community Voice for 50 Years Your Community Voice for 50 Years RRecorecorPONTE VEDVEDRARA dderer entertainmentEEXTRATRA! ! Featuringentertainment TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules,X puzzles and more! E dw P ar , N d S ay ecu y D nda ttne August 19 - 25, 2021 , DO ; Bri ; Jaclyn Taylor, NP We offer: INSIDE: •Intimacy Wellness New listings •Hormone Optimization and Testosterone Replacement Therapy Life for for Netlix, Hulu & •Stress Urinary Incontinence for Women Amazon Prime •Holistic Approach to Weight Loss •Hair Restoration ‘The Walking Pages 3, 17, 22 •Medical Aesthetic Injectables •IV Hydration •Laser Hair Removal Dead’ is almost •Laser Skin Rejuvenation Jeffrey Dean Morgan is among •Microneedling & PRP Facial the stars of “The Walking •Weight Management up as Season •Medical Grade Skin Care and Chemical Peels Dead,” which starts its final 11 starts season Sunday on AMC. 904-595-BLUE (2583) blueh2ohealth.com 340 Town Plaza Ave. #2401 x 5” ad Ponte Vedra, FL 32081 One of the largest injury judgements in Florida’s history: $228 million. (904) 399-1609 4 x 3” ad BY JAY BOBBIN ‘The Walking Dead’ walks What’s Available NOW On into its final AMC season It’ll be a long goodbye for “The Walking Dead,” which its many fans aren’t likely to mind. The 11th and final season of AMC’s hugely popular zombie drama starts Sunday, Aug. 22 – and it really is only the beginning of the end, since after that eight-episode arc ends, two more will wrap up the series in 2022.