Hailes-Castle.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Scotland from the Accession of Alexander III. to The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

On Your Doorstep

Heritage on your doorstep 1–17 SEPTEMBER 2017 east lothian Archaeology & Local History Fortnight BOOKING ESSENTIAL Book online: www.eastlothian.gov.uk/archaeologyfortnight Events (unless marked ) JOINING INSTRUCTIONS GIVEN ON BOOKING FRI 1ST – SUN 10TH SEPT The Big Waggonway Dig East Lothian Archaeology & Local History Fortnight is organised annually by East Lothian Council’s Archaeology Service. Find out more about what we Cockenzie Harbour 10am – 4pm do and events throughout the year at www.eastlothian.gov.uk/archaeology Book your dig session: Led by the 1722 Waggonway Heritage The fortnight is part of Archaeology Scotland’s annual Scottish Archaeology EventsGroup, come and try your hand at COCKENZIE HARBOUR COVER ILLUSTRATION: © ALAN BRABY ILLUSTRATION: COVER Month. For more information visit www.archaeologyscotland.org.uk archaeology as we uncover the remains FRI 1ST – SUN 3RD of part of the Cadell’s 1815 iron railway FRI 8TH & SAT 9TH at Cockenzie Harbour. There are loads DIG SESSIONS of different tasks to help with, from 10am – 3pm Disabled access Primarily for adults 16+ digging to cleaning finds and with Or drop in for a quick try! Partial disabled access Family event ‘living history’ salt making at Cockenzie House & Gardens, storytelling from No disabled access Sturdy footwear/ appropriate clothing Tim Porteus and much, much more. There’s something for all the family. COCKENZIE HOUSE & GARDENS NO DOGS PLEASE EXCEPT GUIDE DOGS. FRI 1ST – SUN 10TH Drop by any time to see the dig, or join a guided tour of the site, daily at 11:30. -

Investigating Murder, Plotting, Romance, Kidnap, Imprisonment, Escape and Execution

The story of Scotland’s most famous queen has everything: battles, INVESTIGATING murder, plotting, romance, kidnap, imprisonment, escape and execution. MARY QUEEN This resource identifies some of the key sites and aims to give teachers OF SCOTS strategies for investigating these sites with primary age pupils. Information for teachers EDUCATION INVESTIGATING HISTORIC SITES: PEOPLE 2 Mary Queen of Scots Using this resource Contents great fun – most pupils find castles and P2 Introduction ruins interesting and exciting. Some of the Using this resource This resource is for teachers investigating sites have replica objects or costumes for P3 the life of Mary Queen of Scots with their pupils to handle. Booking a visit pupils. It aims to link ongoing classroom work with the places associated with the Many of the key sites associated with Mary P4 are, because of their royal connections, in a Supporting learning and queen, and events with the historic sites teaching where they took place. good state of repair. At Stirling there is the great bonus that the rooms of the royal palace P6 NB: This pack is aimed at teachers rather are currently being restored to their 16th- Integrating a visit with than pupils and it is not intended that it century splendour. Many sites are, however, classroom studies should be copied and distributed to pupils. ruinous. Presented properly, this can be a P10 This resource aims to provide: powerful motivator for pupils: What could this Timeline: the life of hole in the floor have been used for? Can you Mary Queen of Scots • an indication of how visits to historic sites can illuminate a study of the work out how the Prestons might defend their P12 dramatic events of the life of Mary castle at Craigmillar? Can anyone see any clues Who’s who: key people Queen of Scots as to what this room used to be? Pupils should in the life of Mary Queen be encouraged at all times to ‘read the stones’ of Scots • support for the delivery of the Curriculum for Excellence and offer their own interpretations of what P14 they see around them. -

East Lothian Combines the Best of Scotland – We We – Scotland of Best the Combines Lothian East Courses, Golf

The Railway Man Railway The Shoebox Zoo Shoebox The House of Mirth of House The Designed and produced by darlingforsyth.com by produced and Designed Castles in the Sky the in Castles McDougall and Mark K Jackson) & Film Edinburgh. Film & Jackson) K Mark and McDougall managers. All other images c/o East Lothian Council (thanks to Rob Rob to (thanks Council Lothian East c/o images other All managers. gov.uk. Musselburgh Racecourse, Gilmerton, Fenton c/o property property c/o Fenton Gilmerton, Racecourse, Musselburgh gov.uk. reproduced courtesy of Historic Scotland. www.historicscotlandimages. Scotland. Historic of courtesy reproduced www.nts.org.uk. Hailes Castle and Tantallon Castle © Crown Copyright Copyright Crown © Castle Tantallon and Castle Hailes www.nts.org.uk. Preston Mill - reproduced courtesy of National Trust for Scotland Scotland for Trust National of courtesy reproduced - Mill Preston #myfilmmoments Images: Locations Images: @filmedinburgh @filmedinburgh Case Histories - thanks to Ruby & ITVGE. Shoebox Zoo - thanks to BBC. BBC. to thanks - Zoo Shoebox ITVGE. & Ruby to thanks - Histories Case www.marketingedinburgh.org/film The Railway Man, Under The Skin, Arn - thanks to the producers. producers. the to thanks - Arn Skin, The Under Man, Railway The To find out more about what’s filmed here, visit: visit: here, filmed what’s about more out find To The Awakening, Castles in the Sky, Young Adam, House of Mirth, Mirth, of House Adam, Young Sky, the in Castles Awakening, The Images: Film/TV Film/TV Images: Images: Borders as a filming destination. filming a as Borders promotes Edinburgh, East Lothian and the Scottish Scottish the and Lothian East Edinburgh, promotes Film Edinburgh, part of Marketing Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Marketing of part Edinburgh, Film beyond. -

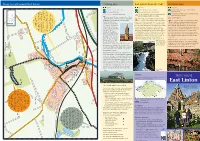

Scottish Natural Heritage Explore for a Day East Lothian

Scottish Natural Heritage Explore for a day East Lothian Explore for a day East Lothian East Lothian combines the best of Scotland! The Lammermuir Symbol Key Hills to the south give way to an expanse of gently rolling rich arable farmland, bounded to the north by 40 miles of Parking Information Centre magnificent coastline. It’s only minutes from Edinburgh by car, train or bus, but feels Paths Disabled Access like a world away. Discover the area and its award winning attractions by following the suggested routes, or simply create your own perfect day. Toilets Wildlife watching Refreshments Picnic Area Admission free unless otherwise stated. 1 1 4.4 Dirleton Castle Romantic Dirleton Castle has graced the heart of the picturesque village of Dirleton since the 13th century. For the first 400 years, it served as the residence of three noble families. It was badly damaged during Cromwell’s siege of 1650, but its fortunes revived in the 1660s when the Nisbet family built a new mansion close to the ruins. The beautiful gardens that grace the castle grounds today date from the late 19th and early 20th centuries and include the world’s longest herbaceous border! Admission charge. Open Apr – Sept 9.30 – 5.30pm; Oct – Mar 9.30 – 4.30pm. Postcode: EH39 5ER Tel: 01620 850330 www.historic-scotland.gov.uk 1.1 Levenhall Links 5 The unlikely setting of a landscaped spoil heap from a power station provides a year round spectacle and an area fast becoming Scotland’s premier birdwatching site. Levenhall boasts a variety of habitats including shallow water scrapes, a boating pond, ash lagoons, hay meadow, woodland and utility grassland. -

Castles – Scotland South East, Lothians

Castles – Scotland South East, Lothians ‘Build Date’ refers to the oldest surviving significant elements In column 1; LT ≡ Lothians Occupation LT CASTLE LOCATION Configuration Build Date Current Remains Status 1 Auldhame NT 602 847 Mansion 16th C Empty, 18th C High walls 2 Barnes NT 528 766 Enclosure 16th C Unfinished Extensive low ruins 3 Binns NT 053 786 Mansion 1620s Occupied Extensions added 4 Blackness NT 056 802 Enclosure 1440s Occupied Now run by HS but habitable 5 Borthwick NT 370 597 Tower + barmkin 1430 Occupied Restored, early 20th C 6 Brunstane NT 201 582 Enclosure 16th C Empty, 18th C Scattered ruins, visible from distance 7 Cairns NT 090 605 Tower 1440 Empty, 18th C High ruin 8 Cakemuir NT 413 591 Tower Mid-16th C Occupied Tower, with added extensions 9 Carberry NT 364 697 Tower 1547 Occupied Much extended, now a hotel 10 Craiglockhart NT 227 703 Tower c1500 Empty Ruin, lowest 2 storeys 11 Craigmillar NT 288 709 Enclosure + tower Late-14th C Empty, 18th C Extensive high ruins 12 Cramond NT 191 769 Tower + barmkin 14th C Occupied Restored, 20th C after period of disuse 13 Crichton NT 380 612 Enclosure 1370 Empty, 18th C Extensive high ruins 14 Dalhousie NT 320 636 Enclosure + tower Mid-15th C Occupied Many additions, now a hotel 15 Dalkeith NT 333 679 Enclosure + tower 15th C Occupied Castle hardly visible in 18th C palace 16 Dirleton NT 518 841 Enclosure 13th C Empty, 17th C Extensive high and low ruins 17 Dunbar NT 678 794 Enclosure? c1070 Empty, 16th C Scattered incoherent fragments 18 Dundas NT 116 767 Tower 1416 Occupied -

Archaeology Fortnight Programme

east lothian Archaeology & Local History Fortnight 30 August - 15 September 2014 Heritage on your doorstep Be part of Scottish Archaeology Month www.eastlothian.gov.uk/archaeology East Lothian Archaeology Disabled access & Local History Fortnight No disabled access Partial disabled access is organised annually by East Lothian Council’s Archaeology Service. To find out more about what A Primarily for adults/ 16+ we do, and about other events held throughout the F Family event year visit www.eastlothian.gov.uk/archaeology Sturdy footwear/ This fortnight is part of Scottish Archaeology Month, appropriate clothing held annually in September by Archaeology Scotland. Please note no dogs, To find out about events held throughout Scotland except guide dogs. visit www.archaeologyscotland.org.uk For more information about events at Historic Scotland properties visit www.historic-scotland.gov.uk and for events at National Trust for Scotland properties visit www.nts.org.uk The John Gray Centre in Haddington brings together the library, archives, museum, and local history centre, and its website provides an opportunity to search archaeology, museums, and archive records for East Lothian: www.johngraycentre.org Booking is essential for many of the events Where booking is required call 01620 827408 or email [email protected] unless otherwise indicated. JOINING INSTRUCTIONS WILL BE GIVEN ON BOOKING. Saturday 30 August Sunday 31 August 10.30am–4.30pm A F 2–3.30pm A F Family History Day St Andrew's Church: John Gray Centre, Haddington Past, Present & Future Launching this year’s Archaeology & Local St Andrew’s Church, Kirk Ports, North Berwick History Fortnight, our theme this year is A look at the church, its history, and future World War One and East Lothian’s military plans for its preservation. -

Historic Scotland Members' Handbook 2020-21

MEMBERS’ HANDBOOK 2020 −21 Enjoy great days out, all year round Historic Scotland. Part of Historic Environment Scotland. WELCOME ...to your Historic Scotland Membership Handbook and welcome to a whole host of special historic places just waiting to be TRACK YOUR VISITS discovered. Why not make 2020 your year We've added boxes to each site listing in the to visit somewhere new, or attend one of index pages at the back of the handbook, for you our exciting events across the country? to mark of when you've visited one of our sites. Your handbook can be used alongside From walks with the Orkney Rangers the Historic Scotland app, which is in the north, to spectacular knights continually updated with a wealth of and their jousting tournament at seasonal and topical information on Caerlaverock Castle in the south, the people and stories of our nation. there’s plenty to keep your diary busy. If you haven’t already done so, download today! historicenvironment.scot/member KEY OPENING TIMES Summer Car parking Self-service tea/cofee (1 Apr 2020 to 30 Sept 2020) Bus parking Shop Mon to Sun 9.30am to 5.30pm Toilets Strong footwear recommended Winter (1 Oct 2020 to 31 Mar 2021) Disabled toilets Bicycle rack Mon to Sun 10am to 4pm Visitor Centre Children’s quiz Opening times and admission prices Mobility scooter available Dogs not permitted are correct at time of publishing, but Site or parts of site may be closed may be liable to change. See page 10 Accessible by public transport at lunch time – please call in advance for further information. -

Family Tree Maker

Ancestors and Descendants of Matthew Thornton Table of Contents Ancestor Tree of Matthew Thornton .....................................................................................................................2 Descendant Tree of Matthew Thornton.................................................................................................................3 Ahnentafel Report of Matthew Thornton...............................................................................................................5 Map......................................................................................................................................................................10 Index....................................................................................................................................................................61 1 Matthew Thornton Ancestors of Matthew Thornton James Thornton b: 15 Nov 1648 in Low Bentham, West Riding (Yorkshire) England m: 14 Feb 1686 in Prestwich, Prestwich (Lancashire) England James Thornton b: Abt. 1684 in Derry, Kilskerry Parish (Tyrone) Northern Ireland m: Abt. 1710 in Ireland d: 07 Nov 1754 in East Derry, Rockingham, New Hampshire Nancy Smith Matthew Thornton b: 1656 in Low Bentham, West Riding (Yorkshire) b: 1714 in Derry, Kilskerry Parish (Tyrone) England Northern Ireland d: 1734 in Derry (Rockingham) New Hampshire m: 1760 in New Hampshire d: 24 Jun 1803 in Newburyport, Essex, Massachusetts Elizabeth Jenkins b: Abt. 1690 in Ireland d: 1741 in East Derry (Rockingham) , NH 2 Descendants -

Tranent to Haddington 21, 18 A1 Road Dualling

SUBJECT ISSUE & PAGE NUMBER A1 42, 16; 43, 28 A1 Road Dualling: Tranent to Haddington 21, 18 A1 Road Dualling: Haddington to Dunbar 42, 16; 43, 28 Abbey Mill 34, 16; 45, 34 Aberlady 13, 13; 59, 45; 60, 39 Aberlady Bay 8, 20; 35, 20 Aberlady Bowling Club 84, 30 Aberlady Cave 57, 30 Aberlady Curling 74, 53 Aberlady Kirk 70, 40 Aberlady Model Railway 57, 39 Acorn Designs 10, 15 Act of Union 27, 9 Adam, Robert 41, 34 Aikengall 53, 28 Airfields 6, 25; 60, 33 Airships 45, 36 Alba Trees 9, 23 Alder, Ruth 50, 49 Alderston House 29, 6 Alexander, Dr Thomas 47, 45 Allison Cargill House, Whittingehame 38, 40 Alpacas 54, 30 Amisfield 16, 14; 74, 46 Amisfield Murder 60, 24 SUBJECT ISSUE & PAGE NUMBER Amisfield Secret Garden 32, 10 Amisfield’s Pineapple House 84, 27 Anderson, Fortescue Lennox Macdonald 80, 26 Anderson, William 22, 31; 87, 23 Angling 80, 24 Angus, George 26, 16 Antiques: Fishing 42, 14 Antiques: Georgian 43, 23 Antiques: Restoration 11, 18 Apple Day at East Linton 62, 17 Apples 34, 13 Appin Equestrian Centre 5, 11; 26, 15 Archaeology: A1 42, 16; 43, 28 Archaeology: AOC 6, 15 Archaeology: Auldhame 58, 28 Archaeology: Brunton Wireworks 74, 32 Archaeology: Buildings 50, 28 Archaeology: East Barns 44, 28 Archaeology: East Lothian 41, 25; 49, 22 Archaeology: East Saltoun Farm 66, 28 Archaeology: Eldbottle, The Lost Village 62, 28 Archaeology: Iron Age Warrior, Dunbar 57, 28 Archaeology: John Muir Birthplace 46, 26 Archaeology: North Berwick 61, 28; 65, 30 Archaeology: Prestongrange 51, 37; 53, 52 SUBJECT ISSUE & PAGE NUMBER Archerfield 60, -

St. Martin's Church, Haddington Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC)ID: PIC162 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90159); Taken into State care: 1911 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2012 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ST MARTIN’S CHURCH, HADDINGTON We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH ST MARTIN’S CHURCH, HADDINGTON SYNOPSIS St. Martin's Kirk, in the Haddington suburb of Nungate, is a rare example in Scotland of a 12th-century parish church. -

Pencraig Brae East Linton Riverside Path

ELintonWalks_rev0806_v1.qxd 8/8/063:58pmPage1 Routes inandaroundEastLinton In 1764, George Buchan succeeded his maternal uncle,George Hepburn,as laird of Smeaton and took the name Buchan- Hepburn.He was created a baronet in 1815.A lawyer by profession,he became a hands-on farmer and noted agricultural reformer.While the 36-roomed mansion he built no longer exists,the parkland trees are a reminder of the fine designed landscape linked to the house.His grandson,Thomas,the third baronet,completed the excavation of the lake in 1830 and planted a magnificent tree collection in an environment offering shelter and humidity.The lake became popular with curlers,but was last used in 1982. Prestonkirk House dominates the entrance to Stories Park.Built in 1865 as the county’s Combination Poorhouse,it served 15 parishes and housed 88 people.It now serves as housing and for the library and Day Centre.Stories Park takes its name from the Storie family of veterinary surgeons,who lived in The Square and kept racehorses in their ‘park’.Francis Storie (d1875) was East Linton’s chief magistrate 1866-72.The Peerie Well,beside the Tyne,supplied the town with water from 1881.If you follow the Tyne up to the Linn Rocks,you come to the original ‘Lintoun’, where the settlement began 1000 years ago. Traprain Law dominates the view to the south. The most significant prehistoric monument in East Lothian,its secrets are still being unearthed. The ancient standing stone along the walk,one of only six in East Lothian,may mark the grave of a local tribal chief.This route was the main road linking Edinburgh and Berwick in mediaeval times,and James VI of Scotland may have passed along here in March 1603 as he travelled south to become James I of England.A new post road (the former A1) was built in 1751.In 1763,there was i one monthly stagecoach between Edinburgh and London,a journey taking 12-16 days.