MMWR, Volume 70, Issue 27 — July 9, 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021-2022 Custom & Standard Information Due Dates

2021-2022 CUSTOM & STANDARD INFORMATION DUE DATES Desired Cover All Desired Cover All Delivery Date Info. Due Text Due Delivery Date Info. Due Text Due May 31 No Deliveries No Deliveries July 19 April 12 May 10 June 1 February 23 March 23 July 20 April 13 May 11 June 2 February 24 March 24 July 21 April 14 May 12 June 3 February 25 March 25 July 22 April 15 May 13 June 4 February 26 March 26 July 23 April 16 May 14 June 7 March 1 March 29 July 26 April 19 May 17 June 8 March 2 March 30 July 27 April 20 May 18 June 9 March 3 March 31 July 28 April 21 May 19 June 10 March 4 April 1 July 29 April 22 May 20 June 11 March 5 April 2 July 30 April 23 May 21 June 14 March 8 April 5 August 2 April 26 May 24 June 15 March 9 April 6 August 3 April 27 May 25 June 16 March 10 April 7 August 4 April 28 May 26 June 17 March 11 April 8 August 5 April 29 May 27 June 18 March 12 April 9 August 6 April 30 May 28 June 21 March 15 April 12 August 9 May 3 May 28 June 22 March 16 April 13 August 10 May 4 June 1 June 23 March 17 April 14 August 11 May 5 June 2 June 24 March 18 April 15 August 12 May 6 June 3 June 25 March 19 April 16 August 13 May 7 June 4 June 28 March 22 April 19 August 16 May 10 June 7 June 29 March 23 April 20 August 17 May 11 June 8 June 30 March 24 April 21 August 18 May 12 June 9 July 1 March 25 April 22 August 19 May 13 June 10 July 2 March 26 April 23 August 20 May 14 June 11 July 5 March 29 April 26 August 23 May 17 June 14 July 6 March 30 April 27 August 24 May 18 June 15 July 7 March 31 April 28 August 25 May 19 June 16 July 8 April 1 April 29 August 26 May 20 June 17 July 9 April 2 April 30 August 27 May 21 June 18 July 12 April 5 May 3 August 30 May 24 June 21 July 13 April 6 May 4 August 31 May 25 June 22 July 14 April 7 May 5 September 1 May 26 June 23 July 15 April 8 May 6 September 2 May 27 June 24 July 16 April 9 May 7 September 3 May 28 June 25. -

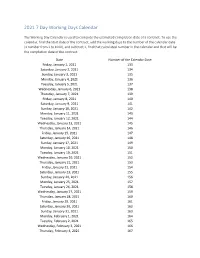

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

Salary Payroll Schedule - 2021 Fiscal Pay Salary Overtime &Retro Leave Semester Pay Period HR Transaction Deadline Payday Days Year Number Entry (PHAHOUR) Periods

Salary Payroll Schedule - 2021 Fiscal Pay Salary Overtime &Retro Leave Semester Pay Period HR Transaction deadline Payday Days Year Number Entry (PHAHOUR) Periods December 25 – January 9 1 Monday, January 4, 2021 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 Friday, January 15, 2021 11 12 January 10 – January 24 2 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 Thursday, January 21, 2021 Monday, February 1, 2021 10 1 January 25 – February 9 3 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 Thursday, February 4, 2021 Tuesday, February 16, 2021 12 February 10 – February 24 4 Tuesday, February 16, 2021 Thursday, February 18, 2021 Monday, March 1, 2021 11 Spring Semester 2 Classes Begin February 25 – March 9 5 Wednesday, March 3, 2021 Friday, March 5, 2021 Tuesday, March 16, 2021 9 1/19/21 Exams End 5/13/21 21 March 10 – March 24 6 Thursday, March 18, 2021 Monday, March 22, 2021 Wednesday, March 31, 2021 11 3 March 25 – April 9 7 Monday, April 5, 2021 Wednesday, April 7, 2021 Friday, April 16, 2021 12 April 10 – April 24 8 Monday, April 19, 2021 Wednesday, April 21, 2021 Friday, April 30, 2021 10 4 April 25 – May 9 9 Monday, May 3, 2021 Wednesday, May 5, 2021 Friday, May 14, 2021 10 May 10 – May 24 10 Tuesday, May 18, 2021 Thursday, May 20, 2021 Tuesday, June 1, 2021 11 Summer I 5 Classes Begin May 25 – June 9 11 Thursday, June 3, 2021 Monday, June 7, 2021 Wednesday, June 16, 2021 12 5/24/21 (Paid 7/1/21) June 10 – June 24 12 Friday, June 18, 2021 Tuesday, June 22, 2021 Thursday, July 1, 2021 11 6 June 25 – July 9 13 Friday, July 2, 2021 Wednesday, July 7, 2021 Friday, July 16, 2021 11 Summer II Classes -

2020-2021 Academic Calendar Revised 9.18.20

FRANCISCAN UNIVERSITY OF STEUBENVILLE 2020-2021 ACADEMIC CALENDAR REVISED 9.18.20 FALL 2020 SEMESTER SPRING 2021 SEMESTER August 24 25-December 11 January 11-May 5 New Student Orientation August 20-23 (Thurs-Sun) January 7-10 (Thurs-Sun) Convocation & Opening of School Mass August 24 (Mon) (4 pm; 3 pm classes January 11 (Mon) (mass only, 10:30 am) shortened & 4:30 pm classes cancelled) Classes begin August 24 (Mon) January 11 (Mon) (10 a.m. classes shortened) Last day for late registration August 28 (Fri) January 15 (Fri) Last day for adding/dropping courses September 2 (Wed) January 20 (Wed) Labor Day (class day) September 7 (Mon) (class day) N/A March for Life N/A January 29 (no day classes) Last day for audit changes September 11 (Fri) January 22 (Fri) Incomplete grades due to registrar September 25 (Fri) February 12 (Fri) Feast of St. Francis October 4 (Sun) N/A Homecoming weekend October 2-4 (Fri-Sun) N/A Midterm deficiencies due to registrar October 14 (Wed) March 5 (Fri) Spring Break N/A March 8-12 (Mon-Fri) (classes resume Mon, March 15) Last day for course withdrawal November 2 (Mon) March 26 (Fri) Tentative Class Make-up Days November 14, 21 (Sat) Thanksgiving vacation November 25-29 (Wed-Sun) N/A (classes resume Mon, Nov 30) Holy Thursday April 1 (no evening classes) Easter recess (Friday & Monday day classes N/A April 2-April 5 (day) canceled; *Monday evening classes do meet) (classes resume Mon evening, April 5, Tuesday day, April 6) Classes Resume Evening: Mon, April 5; Day: Tues, April 6 Last day of classes December 1 (Tues) -

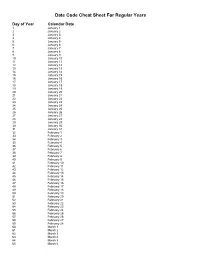

Julian Date Cheat Sheet for Regular Years

Date Code Cheat Sheet For Regular Years Day of Year Calendar Date 1 January 1 2 January 2 3 January 3 4 January 4 5 January 5 6 January 6 7 January 7 8 January 8 9 January 9 10 January 10 11 January 11 12 January 12 13 January 13 14 January 14 15 January 15 16 January 16 17 January 17 18 January 18 19 January 19 20 January 20 21 January 21 22 January 22 23 January 23 24 January 24 25 January 25 26 January 26 27 January 27 28 January 28 29 January 29 30 January 30 31 January 31 32 February 1 33 February 2 34 February 3 35 February 4 36 February 5 37 February 6 38 February 7 39 February 8 40 February 9 41 February 10 42 February 11 43 February 12 44 February 13 45 February 14 46 February 15 47 February 16 48 February 17 49 February 18 50 February 19 51 February 20 52 February 21 53 February 22 54 February 23 55 February 24 56 February 25 57 February 26 58 February 27 59 February 28 60 March 1 61 March 2 62 March 3 63 March 4 64 March 5 65 March 6 66 March 7 67 March 8 68 March 9 69 March 10 70 March 11 71 March 12 72 March 13 73 March 14 74 March 15 75 March 16 76 March 17 77 March 18 78 March 19 79 March 20 80 March 21 81 March 22 82 March 23 83 March 24 84 March 25 85 March 26 86 March 27 87 March 28 88 March 29 89 March 30 90 March 31 91 April 1 92 April 2 93 April 3 94 April 4 95 April 5 96 April 6 97 April 7 98 April 8 99 April 9 100 April 10 101 April 11 102 April 12 103 April 13 104 April 14 105 April 15 106 April 16 107 April 17 108 April 18 109 April 19 110 April 20 111 April 21 112 April 22 113 April 23 114 April 24 115 April -

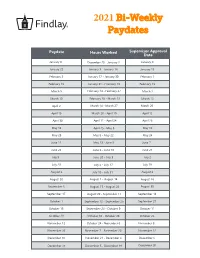

2021 Bi-Weekly Paydates

2021 Bi-Weekly Paydates Paydate Hours Worked Supervisor Approval Date January 8 December 20 - January 2 January 4 January 22 January 3 - January 16 January 15 February 5 January 17 - January 30 February 1 February 19 January 31 - February 13 February 15 March 5 February 14 - February 27 March 1 March 19 February 28 - March 13 March 15 April 2 March 14 - March 27 March 29 April 16 March 28 - April 10 April 12 April 30 April 11 - April 24 April 26 May 14 April 25 - May 8 May 10 May 28 May 9 - May 22 May 24 June 11 May 23 - June 5 June 7 June 25 June 6 - June 19 June 21 July 9 June 20 - July 3 July 2 July 23 July 4 - July 17 July 19 August 6 July 18 - July 31 August 2 August 20 August 1 - August 14 August 16 September 3 August 15 - August 28 August 30 September 17 August 29 - September 11 September 13 October 1 September 12 - September 25 September 27 October 15 September 26 - October 9 October 11 October 29 October 10 - October 23 October 25 November 12 October 24 - November 6 November 8 November 26 November 7 - November 20 November 22 December 10 November 21 - December 4 December 6 December 24 December 5 - December 18 December 20 2021 Bi-Weekly Paydate/Holiday Paydates January February March April Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 3 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 -

Pay Date Calendar

Pay Date Information Select the pay period start date that coincides with your first day of employment. Pay Period Pay Period Begins (Sunday) Pay Period Ends (Saturday) Official Pay Date (Thursday)* 1 January 10, 2016 January 23, 2016 February 4, 2016 2 January 24, 2016 February 6, 2016 February 18, 2016 3 February 7, 2016 February 20, 2016 March 3, 2016 4 February 21, 2016 March 5, 2016 March 17, 2016 5 March 6, 2016 March 19, 2016 March 31, 2016 6 March 20, 2016 April 2, 2016 April 14, 2016 7 April 3, 2016 April 16, 2016 April 28, 2016 8 April 17, 2016 April 30, 2016 May 12, 2016 9 May 1, 2016 May 14, 2016 May 26, 2016 10 May 15, 2016 May 28, 2016 June 9, 2016 11 May 29, 2016 June 11, 2016 June 23, 2016 12 June 12, 2016 June 25, 2016 July 7, 2016 13 June 26, 2016 July 9, 2016 July 21, 2016 14 July 10, 2016 July 23, 2016 August 4, 2016 15 July 24, 2016 August 6, 2016 August 18, 2016 16 August 7, 2016 August 20, 2016 September 1, 2016 17 August 21, 2016 September 3, 2016 September 15, 2016 18 September 4, 2016 September 17, 2016 September 29, 2016 19 September 18, 2016 October 1, 2016 October 13, 2016 20 October 2, 2016 October 15, 2016 October 27, 2016 21 October 16, 2016 October 29, 2016 November 10, 2016 22 October 30, 2016 November 12, 2016 November 24, 2016 23 November 13, 2016 November 26, 2016 December 8, 2016 24 November 27, 2016 December 10, 2016 December 22, 2016 25 December 11, 2016 December 24, 2016 January 5, 2017 26 December 25, 2016 January 7, 2017 January 19, 2017 1 January 8, 2017 January 21, 2017 February 2, 2017 2 January -

COVID-19 Dashboard - Thursday, July 09, 2020 Dashboard of Public Health Indicators

7/9/2020 Duplicate of Public Health Indicators Massachusetts Department of Public Health COVID-19 Dashboard - Thursday, July 09, 2020 Dashboard of Public Health Indicators Newly Reported Total Confirmed Newly Reported Total Deaths Confirmed Cases Cases Deaths among among Confirmed Today Confirmed Today Cases 177 105,138 25 8,053 New Individuals Total Individuals Below is the status as of June 5, 2020: Tested by Tested by Molecular Tests Molecular Tests Measure Status 9,648 920,002 COVID-19 positive test rate ⚫ Number of individuals who died from COVID-19 ⚫ Number of patients with COVID-19 in hospitals ⚫ Total Molecular Legend Tests Healthcare system readiness ⚫ Administered Testing capacity ⚫ 1,171,180 Contact tracing capabilities ⚫ Please note: The front page of the dashboard has been reformatted. Probable case and death information can be found on page 21. Antibody tests (individual and total numbers) can be found on page 7. 1 1/1 7/9/2020 Public Health Indicators2 Massachusetts Department of Public Health COVID-19 Dashboard - Thursday, July 09, 2020 Percent Change Since Dashboard of Public Health Indicators April 15th 7 Day Weighted 4% 3.9% 3.1% 2.9% 2.8% Average of Positive 3.5% 2.7% 2.5% 2.2% 2.1% Molecular Test 2.0% 1.9% 1.9% 1.9% 1.9% 2.0% 2.0% 2.0% 1.9% 1.9% 1.9% 1.9% 1.9% 1.9% 1.9% 2% Rate -93% 1.9% 1.9% 2.0% 1.9% 1.8% 1.9% June June June June June June June June June June June June June June June June June June June June June June July July July July July July July July 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 -

2021 Park Hours

Holiday World & Splashin' Safari 2021 Operating Calendar May, 2021 Holiday World Hours Splashin' Safari Hours Special Events Saturday, May 1 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Sunday, May 2 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Monday, May 3 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Tuesday, May 4 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Wednesday, May 5 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Thursday, May 6 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Friday, May 7 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Saturday, May 8 Platinum Season Pass Preview Day: Holiday World is open from 10 AM until 6 PM Splashin' Safari is Closed Platinum Season Passholder Party Sunday, May 9 Passholder Preview Day: Holiday World is open from 10 AM until 6 PM Splashin' Safari is Closed Monday, May 10 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Tuesday, May 11 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Wednesday, May 12 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Thursday, May 13 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Friday, May 14 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed for a private outing Saturday, May 15 Holiday World is open from 10 AM until 4 PM Splashin' Safari is Closed Sunday, May 16 Holiday World is open from 10 AM until 4 PM Splashin' Safari is Closed Monday, May 17 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Tuesday, May 18 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Wednesday, May 19 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Thursday, May 20 Holiday World & Splashin' Safari are closed Friday, May 21 Holiday -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 131/Tuesday, July 9, 2019/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 131 / Tuesday, July 9, 2019 / Notices 32821 intended to be solicited with respect to business days between the hours of Business Administration Rules and the proposed rule change and none have 10:00 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. Copies of such Regulations (13 CFR 107.1900) to been received. filing also will be available for function as a small business investment inspection and copying at the principal company under the Small Business III. Date of Effectiveness of the office of OCC and on OCC’s website at Investment Company License No. 05/ Proposed Rule Change and Timing for https://www.theocc.com/about/ 05–0274 issued to Prairie Capital III QP, Commission Action publications/bylaws.jsp. L.P. said license is hereby declared null Within 45 days of the date of All comments received will be posted and void. publication of this notice in the Federal without change. Persons submitting United States Small Business Register or within such longer period comments are cautioned that we do not Administration. up to 90 days (i) as the Commission may redact or edit personal identifying Dated: July 1, 2019. designate if it finds such longer period information from comment submissions. A. Joseph Shepard, to be appropriate and publishes its You should submit only information reasons for so finding or (ii) as to which Associate Administrator for Investment and that you wish to make available Innovation. the self-regulatory organization publicly. consents, the Commission will: All submissions should refer to File [FR Doc. 2019–14603 Filed 7–8–19; 8:45 am] (A) By order approve or disapprove Number SR–OCC–2019–005 and should BILLING CODE 8025–01–P the proposed rule change, or be submitted on or before July 30, 2019. -

2021 Swim Calendar

LifeQuestFitness.net | 509-545-5191 2021 2 Day per Week Classes 2 Day per Week Classes 2 Day per Week Classes April 12 - May 27 (7 weeks) April 12 - May 27 (7 weeks) June 2 - July 1 (4 1/2 weeks) 1 Day per Week Classes 1 Day per Week Classes 1 Day per Week Classes APRIL April 16 - May 22 (6 weeks) MAY April 16 - May 22 (6 weeks) JUNE June 4 - June 26 (4 weeks) SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 4 5 6 7 8 9 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 11 12 13 14 15 16 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 18 19 20 21 22 23 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 25 26 27 28 29 30 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 27 28 29 30 30 31 30 2 Day per Week Classes 2 Day per Week Classes 2 Day per Week Classes July 5 - July 29 (4 weeks) August 2 - 26 (4 weeks) Sept 8 - 30 (3 1/2 weeks) 1 Day per Week Classes 1 Day per Week Classes EPTEMBER 1 Day per Week Classes JULY July 9 - July 31 (4 weeks) AUGUST August 6 -28 (4 weeks) S Sept 10 - Oct 2 (4 weeks) SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY 1 2 3 1 1 2 3 4 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 8 9 10 11 12 13 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 15 16 17 18 19 20 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 22 23 24 25 26 27 26 27 28 29 30 29 30 31 2 Day per Week Classes 2 Day per Week Classes 2 Day per Week Classes -

2016 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2016 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2016 306 Saturday, January 2, 2016 307 Sunday, January 3, 2016 308 Monday, January 4, 2016 309 Tuesday, January 5, 2016 310 Wednesday, January 6, 2016 311 Thursday, January 7, 2016 312 Friday, January 8, 2016 313 Saturday, January 9, 2016 314 Sunday, January 10, 2016 315 Monday, January 11, 2016 316 Tuesday, January 12, 2016 317 Wednesday, January 13, 2016 318 Thursday, January 14, 2016 319 Friday, January 15, 2016 320 Saturday, January 16, 2016 321 Sunday, January 17, 2016 322 Monday, January 18, 2016 323 Tuesday, January 19, 2016 324 Wednesday, January 20, 2016 325 Thursday, January 21, 2016 326 Friday, January 22, 2016 327 Saturday, January 23, 2016 328 Sunday, January 24, 2016 329 Monday, January 25, 2016 330 Tuesday, January 26, 2016 331 Wednesday, January 27, 2016 332 Thursday, January 28, 2016 333 Friday, January 29, 2016 334 Saturday, January 30, 2016 335 Sunday, January 31, 2016 336 Monday, February 1, 2016 337 Tuesday, February 2, 2016 338 Wednesday, February 3, 2016 339 Thursday, February 4, 2016 340 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2016 341 Saturday, February 6, 2016 342 Sunday, February