Lethal and Sublethal Effects of Pesticides Used in Western United States Orchards on Hippodamia Convergens by Lisa Fernandez A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDEX to PESTICIDE TYPES and FAMILIES and PART 180 TOLERANCE INFORMATION of PESTICIDE CHEMICALS in FOOD and FEED COMMODITIES

US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Pesticide Programs INDEX to PESTICIDE TYPES and FAMILIES and PART 180 TOLERANCE INFORMATION of PESTICIDE CHEMICALS in FOOD and FEED COMMODITIES Note: Pesticide tolerance information is updated in the Code of Federal Regulations on a weekly basis. EPA plans to update these indexes biannually. These indexes are current as of the date indicated in the pdf file. For the latest information on pesticide tolerances, please check the electronic Code of Federal Regulations (eCFR) at http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_07/40cfrv23_07.html 1 40 CFR Type Family Common name CAS Number PC code 180.163 Acaricide bridged diphenyl Dicofol (1,1-Bis(chlorophenyl)-2,2,2-trichloroethanol) 115-32-2 10501 180.198 Acaricide phosphonate Trichlorfon 52-68-6 57901 180.259 Acaricide sulfite ester Propargite 2312-35-8 97601 180.446 Acaricide tetrazine Clofentezine 74115-24-5 125501 180.448 Acaricide thiazolidine Hexythiazox 78587-05-0 128849 180.517 Acaricide phenylpyrazole Fipronil 120068-37-3 129121 180.566 Acaricide pyrazole Fenpyroximate 134098-61-6 129131 180.572 Acaricide carbazate Bifenazate 149877-41-8 586 180.593 Acaricide unclassified Etoxazole 153233-91-1 107091 180.599 Acaricide unclassified Acequinocyl 57960-19-7 6329 180.341 Acaricide, fungicide dinitrophenol Dinocap (2, 4-Dinitro-6-octylphenyl crotonate and 2,6-dinitro-4- 39300-45-3 36001 octylphenyl crotonate} 180.111 Acaricide, insecticide organophosphorus Malathion 121-75-5 57701 180.182 Acaricide, insecticide cyclodiene Endosulfan 115-29-7 79401 -

Assessing the Single and Combined Toxicity of Chlorantraniliprole And

toxins Article Assessing the Single and Combined Toxicity of Chlorantraniliprole and Bacillus thuringiensis (GO33A) against Four Selected Strains of Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae), and a Gene Expression Analysis Muhammad Zeeshan Shabbir 1,2, Ling He 1,2, Changlong Shu 3, Fei Yin 1,2, Jie Zhang 3 and Zhen-Yu Li 1,2,* 1 Institute of Plant Protection, Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Guangzhou 510640, China; [email protected] (M.Z.S.); [email protected] (L.H.); [email protected] (F.Y.) 2 Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of High Technology for Plant Protection, Guangzhou 510640, China 3 State Key Laboratory for Biology of Plant Diseases and Insect Pests, Institute of Plant Protection, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing 100094, China; [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (J.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Concerns about resistance development to conventional insecticides in diamondback moth (DBM) Plutella xylostella (L.), the most destructive pest of Brassica vegetables, have stimulated interest in alternative pest management strategies. The toxicity of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. aizawai (Bt GO33A) combined with chlorantraniliprole (Chl) has not been documented. Here, we examined sin- gle and combined toxicity of chlorantraniliprole and Bt to assess the levels of resistance in four DBM strains. Additionally, enzyme activities were tested in field-original highly resistant (FOH-DBM), Bt-resistant (Bt-DBM), chlorantraniliprole-resistant (CL-DBM), and Bt + chlorantraniliprole-resistant (BtC-DBM) strains. The Bt product had the highest toxicity to all four DBM strains followed by the Citation: Shabbir, M.Z.; He, L.; Shu, mixture of insecticides (Bt + Chl) and chlorantraniliprole. -

Chlorantraniliprole: Reduced-Risk Insecticide for Controlling Insect Pests of Woody Ornamentals with Low Hazard to Bees

242 Redmond and Potter: Acelepryn Control of Horticultural Pests Arboriculture & Urban Forestry 2017. 43(6):242–256 Chlorantraniliprole: Reduced-risk Insecticide for Controlling Insect Pests of Woody Ornamentals with Low Hazard to Bees Carl T. Redmond and Daniel A. Potter Abstract. Landscape professionals need target-selective insecticides for managing insect pests on flowering woody orna- mentals that may be visited by bees and other insect pollinators. Chlorantraniliprole, the first anthranilic diamide insec- ticide registered for use in urban landscapes, selectively targets the receptors that regulate the flow of calcium to control muscle contraction in caterpillars, plant-feeding beetles, and certain other phytophagous insects. Designated a reduced- risk pesticide by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, it has a favorable toxicological and environmental profile, including very low toxicity to bees and most types of predatory and parasitic insects that contribute to pest sup- pression. Chlorantraniliprole has become a mainstay for managing turfgrass pests, but little has been published concern- ing its performance against the pests of woody ornamentals. Researchers evaluated it against pests spanning five different orders: adult Japanese beetles, evergreen bagworm, eastern tent caterpillar, bristly roseslug sawfly, hawthorn lace bug, ole- ander aphid, boxwood psyllid, oak lecanium scale (crawlers), and boxwood leafminer, using real-world exposure scenarios. Chlorantraniliprole’s efficacy, speed of control, and residual activity as a foliar spray for the leaf-chewing pests was as good, or better, than provided by industry standards, but sprays were ineffective against the sucking pests (lace bugs, aphids, or scales). Basal soil drenches in autumn or spring failed to systemically control boxwood psyllids or leafminers, but autumn drenches did suppress roseslug damage and Japanese beetle feeding the following year. -

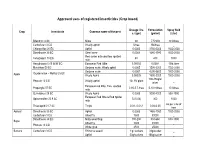

Approved Uses of Registered Insecticides (Crop Based)

Approved uses of registered insecticides (Crop based) Dosage / ha Formulation Spray fluid Crop Insecticide Common name of the pest a.i (gm) (gm/ml) (Liter) Bifenthrin 8 SC Mites 60 7.5ml/lit 10 lit/tree Carbofuran 3 CG Woolly aphid 5/tree 166/tree _ Chlorpyrifos 20 EC Aphid 0.0005 3750-5000 1500-2000 Dimethoate 30 EC Stem borer 0.0003 1485-1980 1500-2000 Red spider mite and two spotted Fenazaquin 10 EC 40 400 1000 mite Hexythiazox 5.45 W/W EC European Red Mite 0.00002 0.0004 10ltr./tree Malathion 50 EC Sanjose scale, Wooly aphid 0.0005 1500-2000 1500-2000 Sanjose scale 0.0007 4200-5600 1500-2000 Oxydemeton – Methyl 25 EC Apple Wooly Aphid 0.00025 1500-2000 1500-2000 100-150gm/ Phorate 10 CG Woolly aphid 10- 15/ plant _ plant European red Mite, Two spotted Propargite 57 EC 2.85-5.7 /tree 5-10 ml/tree 10 lit/tree mite Quinalphos 25 EC Wooly Aphid 0.0005 3000-4000 500-1000 European Red Mite & Red Spider Spiromesifen 22.9 SC 72(0.03) 300 1000 mite As per size of Thiacloprid 21.7 SC Thrips 0.01- 0.012 0.04-0.05 tree Apricot Dimethoate 30 EC Aphid 0.0003 1485-1980 1500-2000 Carbofuran 3 CG Shoot fly 1500 50000 _ Dimethoate 30 EC Milky weed bug 180-200 594-660 500-1000 Bajra Shoot fly 3000 30000 _ Phorate 10 CG White grub 2500 25000 _ Banana Carbofuran 3 CG Rhizome weevil 1 g/ suckers 33g/sucker _ Aphid 50g/suckers 166g/sucker _ Nematode 1.5g/suckers 50g/suckers _ Dimethoate 30 EC Aphid, Lace wing bug 0.0003 1485-1980 1500-2000 Tingyi bug 0.00025 1500-2000 1500-2000 Oxydemeton – Methyl 25 EC Aphids 0.0005 3000-4000 1500-2000 2.5 -1.25/ 25 -12.5/ Phorate 10 CG Aphid _ plant plant Quinalphos 25 EC Tingid bug 0.0005 3000-4000 500-1000 Phosalone 35 EC Aphid 500 1428 500-1000 Aphid 1000 33300 _ Barely Carbofuran 3 CG Jassid 1250 41600 _ Cyst nematode 1000 33300 _ Phorate 10 CG Aphid 1000 10000 _ Beans Chlorpyrifos 20 EC Pod borer , Black bug 600 3000 500-1000 Chlorantraniliprole 18.5 SC Pod borers 25 125 500 Chlorpyrifos 1.5 DP Helicoverpa armigera 375 25000 _ Azadirachtin 0.03 (300 PPM) Pod Borer _ _ _ Bacillus thuringiensis Var. -

The Fall Armyworm – a Pest of Pasture and Hay

The Fall Armyworm – A Pest of Pasture and Hay. Allen Knutson Extension Entomologist, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center, Dallas, 2019 revision The fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, is a common pest of bermudagrass, sorghum, corn, wheat and rye grass and many other crops in north and central Texas. Larvae of fall armyworms are green, brown or black with white to yellowish lines running from head to tail. A distinct white line between the eyes forms an inverted “Y” pattern on the face. Four black spots aligned in a square on the top of the segment near the back end of the caterpillar are also characteristic. Armyworms are very small (less than 1/8 inch) at first, cause little plant damage and as a result often go unnoticed. Larvae feed for 2-3 weeks and full grown larvae are about 1 to 1 1/2 inches long. Given their immense appetite, great numbers, and marching ability, fall armyworms can damage entire fields or pastures in a few days. Once the armyworm larva completes feeding, it tunnels into the soil to a depth of about an inch and enters the pupal stage. The armyworm moth emerges from the pupa in about ten days and repeats the life cycle. The fall armyworm moth has a wingspan of about 1 1/2 inches. The front pair of wings is dark gray with an irregular pattern of light and dark areas. Moths are active at night when they feed on nectar and deposit egg masses. A single female can deposit up to 2000 eggs and there are four to five generations per year. -

Impacts of Insecticides on Predatory Mite, Neoseiulus Fallacis (Acari: Phytoseidae) and Mite Flaring of European Red Mites, Panonychus Ulmi (Acari: Tetranychidae)

IMPACTS OF INSECTICIDES ON PREDATORY MITE, NEOSEIULUS FALLACIS (ACARI: PHYTOSEIDAE) AND MITE FLARING OF EUROPEAN RED MITES, PANONYCHUS ULMI (ACARI: TETRANYCHIDAE) By Raja Zalinda Raja Jamil A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Entomology–Doctor of Philosophy 2014 ABSTRACT IMPACTS OF INSECTICIDES ON PREDATORY MITE, NEOSEIULUS FALLACIS (ACARI: PHYTOSEIDAE) AND MITE FLARING OF EUROPEAN RED MITES, PANONYCHUS ULMI (ACARI: TETRANYCHIDAE) By Raja Zalinda Raja Jamil Panonychus ulmi, the European red mite, is a major agricultural pest found in most deciduous fruit growing areas. It is the most important mite species attacking tree fruits in humid regions of North America. Bristle-like mouthparts of this mite species pierce the leaf cell wall and ingestion of their contents including chlorophyll causes bronzing injury to leaves. Heavy mite feeding early in the season (late Jun and July) reduce tree growth and yield as well as the fruit bud formation, thereby reduce yields the following year. Biological control of this pest species by predators has been a cornerstone of IPM. Phytoseiid mite, Neoseiulus fallacis (Garman) is the most effective predator mite in Michigan apple orchards and provides mid- and late-season biological control of European red mites. Achieving full potential of biological control in tree fruit has been challenging due to the periodic sprays of broad-spectrum insecticides. There have been cases of mite flaring reported by farmers in relation to the reduced-risk (RR) insecticides that were registered in commercial apple production in the past ten years. These insecticides are often used in fruit trees to control key direct pests such as the codling moth. -

Cyantraniliprole

PUBLIC RELEASE SUMMARY on the Evaluation of the New Active Constituent Cyantraniliprole in the Product DuPont Exirel Insecticide APVMA Product Number 64103 OCTOBER 2013 © Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority 2013 ISSN: 1443-1335 (electronic) ISBN: 978-1-922188-50-2 (electronic) Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA). Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms and other elements specifically identified, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence. This is a standard form agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. A summary of the licence terms is available from www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en. The full licence terms are available from www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/legalcode. The APVMA’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any approved material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: licensed from the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence. In referencing this document the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority should be cited as author, publisher and copyright owner. Use of the Coat of Arms The terms under which the Coat of Arms can be used are set out on the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet website (see www.dpmc.gov.au/guidelines). -

And Trans-Acting Variants Contribute to Survivorship in a Na Ve Drosophila Melanogaster Population Exposed to Ryanoid Insec

Cis- and trans-acting variants contribute to survivorship in a naïve Drosophila melanogaster population exposed to ryanoid insecticides Llewellyn Greena, Paul Battlaya, Alexandre Fournier-Levela, Robert T. Gooda, and Charles Robina,1 aSchool of BioSciences, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia Edited by Trudy F. C. Mackay, Clemson University, Raleigh, NC, and approved April 16, 2019 (received for review December 20, 2018) Insecticide resistance is a paradigm of microevolution, and insecti- others that suggest that resistance to this new insecticide class can cides are responsible for the strongest cases of recent selection in arise through other means (9–12). the genome of Drosophila melanogaster.Hereweuseanaïvepop- While Drosophila melanogaster is not a pest or a direct target ulation and a novel insecticide class to examine the ab initio genetic of chlorantraniliprole applications, it is an organism of interest architecture of a potential selective response. Genome-wide associ- for two reasons. Firstly, D. melanogaster has long served as a ation studies (GWAS) of chlorantraniliprole susceptibility reveal var- model for insecticide resistance (13) and its status as a model iation in a gene of major effect, Stretchin Myosin light chain kinase organism more generally means that there is a wide variety of (Strn-Mlck), which we validate with linkage mapping and transgenic tools available to characterize genetic traits (14). Secondly, se- manipulation of gene expression. We propose that allelic variation lective sweep analyses show that insecticides (particularly the in Strn-Mlck alters sensitivity to the calcium depletion attributable organophosphates) have been major selective agents on D. to chlorantraniliprole’s mode of action. -

Chlorantraniliprole (DPX-E2Y45, Rynaxypyr®, Coragen®) a New Diamide Insecticide… 41

Zbornik predavanj in referatov 9. slovenskega posvetovanja o varstvu rastlin z mednarodno udeležbo 39 Nova Gorica, 4.–5. marec 2009 CHLORANTRANILIPROLE (DPX-E2Y45, RYNAXYPYR®, CORAGEN®), A NEW DIAMIDE INSECTICIDE FOR CONTROL OF CODLING MOTH (Cydia pomonella), COLORADO POTATO BEETLE (Leptinotarsa decemlineata) AND EUROPEAN GRAPEVINE MOTH (Lobesia botrana) Andrea BASSI1, J. L. RISON2, J. A. WILES3 1DuPont Italy Srl 2Du Pont de Nemours (France) SAS 3Du Pont (UK) Limited ABSTRACT Chlorantraniliprole (DPX-E2Y45, Rynaxypyr®, Coragen®) is a new compound by DuPont belonging to a new class of selective insecticides (anthranilic diamides) featuring a novel mode of action (group 28 in the IRAC classification). By activating the insect ryanodine receptors (RyRs) it stimulates the release and depletion of intracellular calcium stores from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of muscle cells, causing impaired muscle regulation, paralysis and ultimately death of sensitive species (Cordova et al. 2006). Extensively tested in the field since 2002, it is registered or next to market introduction in the majority of agricultural countries worldwide. Development in Slovenia is currently focused in foliar applications in apples, potatoes and grapes. In the EU trials, rates of 10-60 g a.s./ha were highly effective on important pests such as: Cydia pomonella, Cydia molesta, Lobesia botrana, Eupoecilia ambiguella, Leptinotarsa decemlineata, Ostrinia nubilalis and Helicoverpa armigera. The product general features have been presented in previous, referenced papers. It has very low toxicity for mammals (both acute and chronic), high intrinsic activity on target pests, strong ovi- larvicidal and larvicidal properties, long lasting crop protection and no cross-resistance to any existing insecticide. Coragen® demonstrated excellent performance on codling moth and other chewing pests, stability of performance across the different conditions and minimal impact on pollinators, beneficial insects and predatory mites. -

Acute Toxicity of Selected Insecticides and Their Safety to Honey Bee (Apis Mellifera L.) Workers Under Laboratory Conditions

Open Access Austin Environmental Sciences Special Article - Pesticides Acute Toxicity of Selected Insecticides and Their Safety to Honey Bee (Apis mellifera L.) Workers Under Laboratory Conditions Abbassy MA1*, Nasr HM1, Abo-yousef HM2 and Dawood RR1 Abstract 1 Department of Plant Protection, Damanhur University, Objectives: The honey bee, Apis mellifera L., is widely used for the Egypt production of honey, wax, pollen, propolis, royal jelly and venom and crop 2Central Laboratory of Pesticides, Ministry of Agriculture pollination. Since honey bees can be exposed to insecticides in sprayed flowering and Land Reclamation, Egypt crops, therefore, this study aimed to assess the acute toxicity and safety index *Corresponding author: Moustafa A Abbassy, of five commonly used insecticides to honey bee workers in laboratory. Department of Plant Protection, Damanhur University, Methods: Bees were exposed to the insecticides: Imidacloprid, Pesticide Chemistry and Toxicology, Egypt Thiamethoxam, Esfenvalerate, Indoxacarb and Chlorantraniliprole by two Received: May 03, 2020; Accepted: May 25, 2020; methods of exposure: topical application and feeding techniques. LD50 and LC50 Published: June 01, 2020 values for each insecticide to honey bees were determined after 24 and 48 h from treatment. Results: The LD50 values in µg per bee were 0.0018 (indoxacarb), 0.019 (esfenvalerate), 0.024 (thiamethoxam), 0.029 (imidacloprid) and 107.12 -1 (chlorantraniliprole). The LC50 values (mg L ), for each insecticide, were as follows: indoxacarb, 0.091; esfenvalerate, 0.014; thiamethoxam, 0.009; imidacloprid, 0.003 and chlorantraniliprole, 0.026, after 24 h from exposure. In general, the neonicotinoid insecticides were the most toxic to bees by feeding technique, and indoxacarb, esfenvalerate were the most toxic by contact method while chlorantraniliprole had slightly or non- toxic effect by the two methods. -

INSECTICIDE RECOMMENDATIONS for SOYBEANS‐ 2017 Raul T

ENT‐13 INSECTICIDE RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SOYBEANS‐ 2017 Raul T. Villanueva, Extension Entomologist Kentucky now ranks among the major soybean producing states. More insect problems have been associated with Kentucky soybeans since it has become a major crop. The following information and control aids should enable the grower to minimize losses due to insect pests on soybeans. Evaluation of Soybean Insect Infestations Fields need to be inspected at least once a week from planting until maturity to assesss the need for and to estimate proper timing for soybean insect control. Shaking soybeans over the row middle will generally be adequate in determining the soybean insects present. A cloth or a newspaper 42" x 24" may be used in the row middle to facilitate counting the soybean insects in almost any row width. Place the cloth between two rows, vigorously shake approximately two row‐feet of plants in each row over the cloth. Count the insects and repeat this process at 10 different locations in the field. If you have no available cloth, use the soil surface as the area for counting insects. Use the average number of insects found for determining when to spray. (Note "Time of Treatment" in Control Tables at the end of this publication.) Determining the percent of defoliation by observing the bean field may be difficult because the dense foliage hides damaged leaves. Pull up plants from several locations in the field and place the leaves against a light background. This method should give a fairly accurate measure of the percent defoliation. Refer to the tables for the percent defoliation to determine if control measures are justified. -

CYANTRANILIPROLE (263) the First Draft Was Prepared by Mr. David Lunn New Zealand Food Safety Authority, Wellington, New Zealand

Cyantraniliprole 361 CYANTRANILIPROLE (263) The first draft was prepared by Mr. David Lunn New Zealand Food Safety Authority, Wellington, New Zealand EXPLANATION Cyantraniliprole is a diamide insecticide with a mode of action (ryanodine receptor activation) similar to chlorantraniliprole and flubendiamide. It has root systemic activity with some translaminar movement and is effective against the larval stages of lepidopteran insects; and also on thrips, aphids, and some other chewing and sucking insects. Authorisations exist for the use of cyantraniliprole in Canada, Columbia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Vietnam and the CLISS countries in West Africa. Authorisations are also being progressed in Australia, Europe and USA under an OECD Joint Review exercise. Cyantraniliprole was scheduled by the Forty-fourth Session of the CCPR as a new compound for consideration by the 2013 JMPR. Residue and analytical aspects of cyantraniliprole were considered for the first time by the present meeting. The manufacturer submitted studies on metabolism, analytical methods, supervised field trials, processing, freezer storage stability, environmental fate in soil and rotational crop residues. In this evaluation, the values presented in the tables are as reported in the various studies, but in the accompanying text, they have generally been rounded to two significant digits. Abbreviations have also been used for the various cyantraniliprole metabolites mentioned in the study reports. These include: IN-F6L99 3-Bromo-N-methyl-1H-pyrazole-5-carboxamide IN-HGW87