Environmental Geology GLG 110 - CHAPTER 4 - ECOLOGY and GEOLOGY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IPBES Workshop on Biodiversity and Pandemics Report

IPBES Workshop on Biodiversity and Pandemics WORKSHOP REPORT *** Strictly Confidential and Embargoed until 3 p.m. CET on 29 October 2020 *** Please note: This workshop report is provided to you on condition of strictest confidentiality. It must not be shared, cited, referenced, summarized, published or commented on, in whole or in part, until the embargo is lifted at 3 p.m. CET/2 p.m. GMT/10 a.m. EDT on Thursday, 29 October 2020 This workshop report is released in a non-laid out format. It will undergo minor editing before being released in a laid-out format. Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services 1 The IPBES Bureau and Multidisciplinary Expert Panel (MEP) authorized a workshop on biodiversity and pandemics that was held virtually on 27-31 July 2020 in accordance with the provisions on “Platform workshops” in support of Plenary- approved activities, set out in section 6.1 of the procedures for the preparation of Platform deliverables (IPBES-3/3, annex I). This workshop report and any recommendations or conclusions contained therein have not been reviewed, endorsed or approved by the IPBES Plenary. The workshop report is considered supporting material available to authors in the preparation of ongoing or future IPBES assessments. While undergoing a scientific peer-review, this material has not been subjected to formal IPBES review processes. 2 Contents 4 Preamble 5 Executive Summary 12 Sections 1 to 5 14 Section 1: The relationship between people and biodiversity underpins disease emergence and provides opportunities -

GE OS 1234-101 Historical Geology Lecture Syllabus Instructor

G E OS 1234-101 Historical Geology Lecture Syllabus Instructor: Dr. Jesse Carlucci ([email protected]), (940) 397-4448 Class: MWF, 10am -10:50am, BO 100 Office hours: Bolin Hall 131, MWF, 11am ± 2pm, Tuesday, noon - 2pm. You can arrange to meet with me at any time, by appointment. Textbook: Earth System History by Steven M. Stanley, 3rd edition. I will occasionally post articles and other readings on blackboard. I will also upload Power Point presentations to blackboard before each class, if possible. Course Objectives: Historical Geology provides the student with a comprehensive survey of the history of life, and major events in the physical development of Earth. Most importantly, this class addresses how processes like plate tectonics and climate interact with life, forming an integrated system. The first half of the class focuses on concepts, and the second on a chronologic overview of major biological and physical events in different geologic periods. L E C T UR E SC H E DU L E Aug 27-31: Overview of course; what is science? The Earth as a planet Stanley (pg. 244-247) Sep 5-7: Earth materials, rocks and minerals Stanley (pg. 13-17; 25-34) Sep 10-14: Rocks & minerals continued; plate tectonics. Stanley (pg. 3-12; 35-46; 128-141; 175-186) Sep 17-21: Geological time and dating of the rock record; chemical systems, the climate system through time. Quiz 1 (Sep 19; 5%). Stanley (pg. 187-194; 196-207; 215-223; 232-238) Sep 24-28: Sedimentary environments and life; paleoecology. Stanley (pg. 76-80; 84-96; 99-123) Oct 1-5: Biological evolution and the fossil record. -

Extreme Environment Technologies for Space and Terrestrial Applications

Extreme Environment Technologies for Space and Terrestrial Applications Tibor S. Balint*, James A. Cutts, Elizabeth A. Kolawa, Craig E. Peterson Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, M/S 301-170U, Pasadena, CA 91109-8099 ABSTRACT Over the next decades, NASA’s planned solar system exploration missions are targeting planets, moons and small bodies, where spacecraft would be expected to encounter diverse extreme environmental (EE) conditions throughout their mission phases. These EE conditions are often coupled. For instance, near the surface of Venus and in the deep atmospheres of giant planets, probes would experience high temperatures and pressures. In the Jovian system low temperatures are coupled with high radiation. Other environments include thermal cycling, and corrosion. Mission operations could also introduce extreme conditions, due to atmospheric entry heat flux and deceleration. Some of these EE conditions are not unique to space missions; they can be encountered by terrestrial assets from the fields of defense, oil and gas, aerospace, and automotive industries. In this paper we outline the findings of NASA’s Extreme Environments Study Team, including discussions on state of the art and emerging capabilities related to environmental protection, tolerance and operations in EEs. We will also highlight cross cutting EE mitigation technologies, for example, between high g-load tolerant impactors for Europa and instrumented projectiles on Earth; high temperature electronics sensors on Jupiter deep probes and sensors inside jet engines; and pressure vessel technologies for Venus probes and sea bottom monitors. We will argue that synergistic development programs between these fields could be highly beneficial and cost effective for the various agencies and industries. -

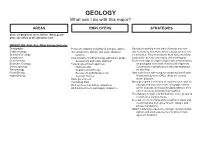

GEOLOGY What Can I Do with This Major?

GEOLOGY What can I do with this major? AREAS EMPLOYERS STRATEGIES Some employment areas follow. Many geolo- gists specialize at the graduate level. ENERGY (Oil, Coal, Gas, Other Energy Sources) Stratigraphy Petroleum industry including oil and gas explora- Geologists working in the area of energy use vari- Sedimentology tion, production, storage and waste disposal ous methods to determine where energy sources are Structural Geology facilities accumulated. They may pursue work tasks including Geophysics Coal industry including mining exploration, grade exploration, well site operations and mudlogging. Geochemistry assessment and waste disposal Seek knowledge in engineering to aid communication, Economic Geology Federal government agencies: as geologists often work closely with engineers. Geomorphology National Labs Coursework in geophysics is also advantageous Paleontology Department of Energy for this field. Fossil Energy Bureau of Land Management Gain experience with computer modeling and Global Hydrogeology Geologic Survey Positioning System (GPS). Both are used to State government locate deposits. Consulting firms Many geologists in this area of expertise work with oil Well services and drilling companies and gas and may work in the geographic areas Oil field machinery and supply companies where deposits are found including offshore sites and in overseas oil-producing countries. This industry is subject to fluctuations, so be prepared to work on a contract basis. Develop excellent writing skills to publish reports and to solicit grants from government, industry and private foundations. Obtain leadership experience through campus organi- zations and work experiences for project man- agement positions. (Geology, Page 2) AREAS EMPLOYERS STRATEGIES ENVIRONMENTAL GEOLOGY Sedimentology Federal government agencies: Geologists in this category may focus on studying, Hydrogeology National Labs protecting and reclaiming the environment. -

Extreme Environments - Ecology - Oxford Bibliographies

Extreme Environments - Ecology - Oxford Bibliographies http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-97801998300... Extreme Environments Robert S. Boyd, Natasha Krell, Nishanta Rajakaruna LAST MODIFIED: 28 JUNE 2016 DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780199830060-0152 Introduction The study of extreme environments is an exploration of the limits of life. Organisms perform a number of basic functions (homeostasis, metabolism, growth, reproduction, etc.), and our water- and carbon-based systems are constrained within certain environmental parameters. Some organisms can push the limits of these environmental boundaries and thrive in what to most other living things are conditions inimical to life. Thus the concept of “extreme” environment is necessarily relative to conditions under which most species thrive. Organisms that live in relatively hostile environments (called extremophiles) include archaea and bacteria, but other groups of organisms also have members that can live in relatively stressful habitats. Scientists point out that there is a difference between living under extreme conditions and tolerating (perhaps by going dormant) extreme conditions, but both situations can help us understand how extreme environments affect life. The adaptations that allow organisms to live in (or survive) extreme conditions are targets of scientific study because they help us understand life’s basic processes and how life responds to environmental challenges. The lessons we learn have important applied aspects because they can help us grow food, process wastes, restore disturbed habitats, and perform many other vital tasks. In this article, we provide sections based on particularly important stress factors, but we also have included sections in which the focus is on major concepts, to show how organisms from extreme environments can inform other areas of scientific interest. -

Biosphere 2 (B2) PI: Katerina Dontsova, Phd Co-PI: Kevin Bonine, Phd Sponsors: National Science Foundation Research Experiences for Undergraduates (NSF REU) Program

Biosphere 2 (B2) PI: Katerina Dontsova, PhD Co-PI: Kevin Bonine, PhD Sponsors: National Science Foundation Research Experiences for Undergraduates (NSF REU) Program BIOSPHERE 2 (B2) Kierstin Acuña The effect of nanochitosan on piñon pine (Pinus edulis) seedling mortality in heatwave conditions University of Maryland, Environmental Science and Policy Mentor: Dr. Dave Breshears, Jason Field and Darin Law – School of Natural Resources and the Environment Abstract Semiarid grasslands worldwide are facing woody plant encroachment, a process that dramatically alters carbon and nutrient cycling. This change in plant types can influence the function of soil microbial communities with unknown consequences for soil carbon cycling and storage. We used soils collected from a five-year passive warming experiment in Southern, AZ to test the effects of warming and substrate availability on microbial carbon use. We hypothesized that substrate addition would increase the diversity of microbial substrate use, and that substrate additions and warming would increase carbon acquisition, creating a positive feedback on carbon mineralization. Community Level Physiological Profiling (CLPP) of microbial activity was conducted using Biolog EcoPlateTMassays from soils collected in July 2018, one week after the start of monsoon rains. Two soil types common to Southern AZ, were amended with one of four treatments (surface juniper wood chips, juniper wood chips incorporated into the soil, surface biochar, or a no-amendment control) and were randomly assigned to a warmed or ambient temperature treatment. We found that surface wood chips resulted in the highest richness and diversity of carbon substrate use with control soils yielding the lowest. Substrate use was positively correlated with the total organic carbon but not with warming. -

Weathering, Erosion, and Susceptibility to Weathering Henri Robert George Kenneth Hack

Weathering, erosion, and susceptibility to weathering Henri Robert George Kenneth Hack To cite this version: Henri Robert George Kenneth Hack. Weathering, erosion, and susceptibility to weathering. Kanji, Milton; He, Manchao; Ribeira e Sousa, Luis. Soft Rock Mechanics and Engineering, Springer Inter- national Publishing, pp.291-333, 2020, 9783030294779. 10.1007/978-3-030-29477-9. hal-03096505 HAL Id: hal-03096505 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03096505 Submitted on 5 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Published in: Hack, H.R.G.K., 2020. Weathering, erosion and susceptibility to weathering. 1 In: Kanji, M., He, M., Ribeira E Sousa, L. (Eds), Soft Rock Mechanics and Engineering, 1 ed, Ch. 11. Springer Nature Switzerland AG, Cham, Switzerland. ISBN: 9783030294779. DOI: 10.1007/978303029477-9_11. pp. 291-333. Weathering, erosion, and susceptibility to weathering H. Robert G.K. Hack Engineering Geology, ESA, Faculty of Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation (ITC), University of Twente Enschede, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] phone: +31624505442 Abstract: Soft grounds are often the result of weathering. Weathering is the chemical and physical change in time of ground under influence of atmosphere, hydrosphere, cryosphere, biosphere, and nuclear radiation (temperature, rain, circulating groundwater, vegetation, etc.). -

Geologic Timeline

SCIENCE IN THE PARK: GEOLOGY GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE ANALOGY PURPOSE: To show students the order of events and time periods in geologic time and the order of events and ages of the physiographic provinces in Virginia. BACKGROUND: Exact dates for events change as scientists explore geologic time. Dates vary from resource to resource and may not be the same as the dates that appear in your text book. Analogies for geologic time: a 24 hour clock or a yearly calendar. Have students or groups of students come up with their own original analogy. Before you assign this activity, you may want to try it, depending on the age of the student, level of the class, or time constraints, you may want to leave out the events that have a date of less than 1 million years. ! Review conversions in the metric system before you begin this activity ! References L.S. Fichter, 1991 (1997) http://csmres.jmu.edu/geollab/vageol/vahist/images/Vahistry.PDF http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/geotime/age.html Wicander, Reed. Historical Geology. Fourth Edition. Toronto, Ontario: Brooks/Cole, 2004. Print. VIRGINIA STANDARDS OF LEARNING ES.10 The student will investigate and understand that many aspects of the history and evolution of the Earth can be inferred by studying rocks and fossils. Key concepts include: relative and absolute dating; rocks and fossils from many different geologic periods and epochs are found in Virginia. Developed by C.P. Anderson Page 1 SCIENCE IN THE PARK: GEOLOGY Building a Geologic Time Scale Time: Materials Meter stick, 5 cm adding machine tape, pencil, colored pencils Procedure 1. -

Arxiv.Org | Cornell University Library, July, 2019. 1

arXiv.org | Cornell University Library, July, 2019. Extremophiles: a special or general case in the search for extra-terrestrial life? Ian von Hegner Aarhus University Abstract Since time immemorial life has been viewed as fragile, yet over the past few decades it has been found that many extreme environments are inhabited by organisms known as extremophiles. Knowledge of their emergence, adaptability, and limitations seems to provide a guideline for the search of extra-terrestrial life, since some extremophiles presumably can survive in extreme environments such as Mars, Europa, and Enceladus. Due to physico-chemical constraints, the first life necessarily came into existence at the lower limit of it‟s conceivable complexity. Thus, the first life could not have been an extremophile, furthermore, since biological evolution occurs over time, then the dual knowledge regarding what specific extremophiles are capable of, and to the analogue environment on extreme worlds, will not be sufficient as a search criterion. This is because, even though an extremophile can live in an extreme environment here-and-now, its ancestor however could not live in that very same environment in the past, which means that no contemporary extremophiles exist in that environment. Furthermore, a theoretical framework should be able to predict whether extremophiles can be considered a special or general case in the galaxy. Thus, a question is raised: does Earth‟s continuous habitability represent an extreme or average value for planets? Thus, dependent on whether it is difficult or easy for worlds to maintain the habitability, the search for extra- terrestrial life with a focus on extremophiles will either represent a search for dying worlds, or a search for special life on living worlds, focusing too narrowly on extreme values. -

Geomorphology and Environmental Geology the Luckiamute Watershed, Central Coast Ranggge, Oregon

Geomorphology and Environmental Geology the Luckiamute Watershed, Central Coast Ranggge, Oregon Greenbelt Land Trust Luckiamute Watershed Council Western Oregon University Field Guide May 10, 2014 123 37.5 123 30 123 22.5 123 15 Dallas West Salem 5 4 44 52.5 Monmouth te ckiamu Little Lu e g n 3 a R Falls 1 City Independence y e 2 l l Pee r a r Helmick e V e Dee iv iv R Sta te e R ut m Park 44 45 ia 99W ck Lu s g n i K 223 k e t e r s C a p o a o C S 44 37.5 Corvallis 34 Albany Blodgett Wren e t Luckiamute Watershed t e Boundary m N la Western Oregon Univ. il 20 W Field Trip Stop Philomath 5 0 5 km Prepared By: Steve Taylor, Ph.D., Professor of Geology Earth and Physical Science Department Chair, Division of Natural Sciences and Mathematics Western Oregon University Monmouth, Oregon 97361 Email: [email protected] Table of Contents TOPIC PAGE Introduction 1-6 Physiographic Setting 7-12 Tectonic Setting 13-16 Bedrock Geology 17-23 Geomorphology Regional Overview 24-28 Geomorphic Research Results 29-35 Vegetation and Invasive Plant Distribution Introduction 36-41 Methodology 42 Invasive Research Results 43-52 Field Trip Stop Summaries and Maps Helmick State Park 55-60 NOTE: Selected pages omitted / recycled from a previous field trip. Field Trip Introduction •People •Introductions •Organizations •Western Oregon University (Earth Science) •Luckiamute Watershed Council •Greenbelt Land Trust •Background •Luckiamute Watershed – Focus of 2001 WOU Environmental Science Institute Course •Undergraduate Science Majors •Pre-service Science Education Majors -

A Geologist Views the Environment

ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 3 3051 00005 3805 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/geologistviewsen42frye EGN 42 557 I16e no. 42 c. 1 ENVIRONMENTAL GEOLOGY NOTES FEBRUARY 1971 • NUMBER 42 A GEOLOGIST VIEWS THE ENVIRONMENT John C. Frye ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY JOHN C. FRYE, Chief • Urbana 61801 A GEOLOGIST VIEWS THE ENVIRONMENT' John C. Frye When the geologist considers the environment, and particularly when he is concerned with the diversified relations of man to his total physical environment, he takes an exceptionally broad and long-term view. It is broad because all of the physical features of the earth are the subject matter of the geologist. It is long term because the geologist views the environment of the moment as a mere point on a very long time-continuum that has witnessed a succession of physical and biological changes—and that at present is dynam- ically undergoing natural change. Let us first consider the time perspective of the geologist, then consider the many physical factors that are important to man's activity on the face of the earth, and, third, turn our attention to specific uses of geologic data for the maintenance or development of an environment that is compatible with human needs. THE LONG VIEW The earth is known to be several billion years old, and the geologic record of physical events and life-forms on the earth is reasonably good for more than the most recent 500 million years. Throughout this span of known time the environment has been constantly changing— sometimes very slowly, but at other times quite rapidly. -

Slum Socio-Ecology: an Exploratory Characterisation of Vulnerability to Climate-Change Related Disasters in the Urban Context

Slum socio-ecology: an exploratory characterisation of vulnerability to climate-change related disasters in the urban context Tilly Alcayna-Stevens Harvard Humanitarian Initiative and Universidad de Oviedo Supervisors: Professor Gregg Greenough and Professor Rafael Castro Date of submission: Wednesday 8 July 2015 This thesis entitled “Slum socio-ecology: an exploratory characterisation of vulnerability to climate-change related disasters in the urban context” is my own work. All sources of information (printed, on websites, etc.) reported by others are indicated in the list of references in accordance with the guidelines. Signature: Total word count: 9,858 I approve this thesis for submission ____________________(supervisor) Contents Glossary of terms .................................................................................................................................... 1 Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Background ............................................................................................................................. 4 1.1.1. Climate change ................................................................................................................ 5 1.1.2. Socio-Ecological Systems ..............................................................................................