Brief of Petitioner for Golan V. Holder; 10-545

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part 1 of the Enemy Within Campaign

® TM ENEMY IN SHADOWS PART 1 OF THE ENEMY WITHIN At the appointed time, we shall rise from our secret places and throw down the towns and cities of the Empire. Chaos will cover this land, and we, the Chosen Servants, shall be exalted in HIS eyes. Hail to Tzeentch, Changer of the Ways! Njawrr’thakh Lzimbarr Tzeentch! ® Enemy in Shadows is the first volume of the revised and updated Director’s Cut of The Enemy Within, one of the most highly regarded roleplaying campaigns ever written. Gather your heroes as you take them from humble beginnings as penniless novice adventurers to the halls of the great and powerful, where nothing is as it seems, and every decision can change the fate of the Empire. Enemy in Shadows begins the five-part series of grim and perilous Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay adventures that inspired a generation of gamers. The Director’s Cut includes insightful commentary with a smattering of dark humour, clever suggestions on new ways to play through the campaign, and a complete guide to Bögenhafen full of exciting locations to visit and explore. Sample file SKU: CB72406 Price: $39.99 PART 1 OF THE ENEMY WITHIN CAMPAIGN 14+ 1-4+ hours 2-7 CB72403 WARHAMMER FANTASY ROLEPLAY CONTENTS THE ENEMY WITHIN THE SCHAFFENFEST One Thing After Another.................. 103 Visiting the Schaffenfest ...................... 55 Flaming Nuisance .............................. 103 WANTED: BOLD ADVENTURERS Optional Encounters ............................ 56 The Ostendamm ................................ 103 Starting the Adventure ......................... 11 Medicine Shows ................................... 56 Warehouse 17 ................................ 104 The Coach and Horses Inn .................. 11 Fortune Tellers ................................ 56 Warehouse 13 ................................ 104 Approaching the Inn ........................... -

THOMAS TURNBULL VFX Supervisor / VFX Producer

THOMAS TURNBULL VFX Supervisor / VFX Producer FEATURE FILMS DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS BEEBA BOYS Deepa Mehta Hamilton-Mehta Productions VFX Supervisor POMPEII (Rocket Science) Paul W.S. Anderson TriStar Pictures VFX Supervisor DOLPHIN TALE 2 (Rocket Science) Charles Martin Smith Alcon Entertainment / Warner Bros. VFX Supervisor QUEEN OF THE NIGHT Atom Egoyan E1 Entertainment VFX Supervisor DEVIL’S KNOT Atom Egoyan Dimension VFX Supervisor RESIDENT EVIL: RETRIBUTION (Rocket Science) Paul W. S. Anderson Constantin Films Int’l / Screen Gems VFX Supervisor SAW 3D: THE FINAL CHAPTER (Rocket Science) Kevin Greutert Lionsgate VFX Supervisor RESIDENT EVIL: AFTERLIFE (Rocket Science) Paul W. S. Anderson Constantin Films Int’l / Screen Gems VFX Supervisor CHLOE Atom Egyon Studio Canal / Sony VFX Consultant SKATELAND (Rocket Science) Anthony Burns Freeman Film / Reversal Films VFX Executive Producer AMELIA (Rocket Science) Mira Nair Fox Searchlight VFX Executive Producer - Uncredited WHITEOUT (Rocket Science) Dominic Sena Warner Bros. VFX Supervisor ADORATION (Rocket Science) Atom Egoyan Serendipity Point Film / Sony VFX Executive Producer RESIDENT EVIL: EXTINCTION (Rocket Science) Russell Mulcahy Constantin Film Int’l / Screen Gems VFX Supervisor LICENSE TO WED (Rocket Science) Ken Kwapis Warner Bros. / Alcon Entertainment VFX Supervisor IN THE NAME OF THE KING: A DUNGEON Uwe Boll Brightlight Pictures SIEGE TALE (Rocket Science) VFX On-Set Supervisor, VFX Supervisor SLITHER (Rocket Science) James Gunn Gold Circle Films / Universal Pictures VFX Supervisor HEAVEN ON EARTH Deepa Mehta Astral Media / CBC VFX Supervisor THE SISTERHOOD OF THE TRAVELING PANTS 2 Sanaa Hamri Warner Bros. VFX Supervisor THE ADVENTURES OF SHARKBOY AND Robert Rodriguez Sony / Dimension Films LAVAGIRL 3-D (ICVFX ) - VFX Technical Advisor THE SISTERHOOD OF THE TRAVELING PANTS Ken Kwapis Alcon Entertainment / Warner Bros. -

About the Away Mission (Formerly Vulcan Events) the Away

About The Away Mission (formerly Vulcan Events) The Away Mission is focused on putting on great events for the fans, producing intimate conventions offering refreshing alternatives to other convention styles that offer one long line after another. Drawing on more than 30 years of industry experience, the Away Mission brings trust and confidence back to the small-convention market. www.away-mission.com ### About the Celebrity Guests William Shatner is a Canadian actor, author, film director, spokesman and comedian. He gained worldwide fame and became a cultural icon for his portrayal of Captain James Tiberius Kirk, commander of the Federation starship USS Enterprise. He has written a series of books chronicling his experiences playing Captain Kirk and being a part of Star Trek, and has co- written several novels set in the Star Trek universe. Shatner also played the veteran police sergeant in T. J. Hooker from 1982 to 1986. From 2004 to 2008, he starred as attorney Denny Crane in the television dramas The Practice and its spin-off Boston Legal, for which he won two Emmy Awards and a Golden Globe Award. Since then he is busier than ever producing and directing two documentaries, making several guest TV appearances, and releasing the non-fiction book "Shatner Rules" which is the basis of his one man show which he performs in select cities around the country. Alice Eve is best known by Star Trek fans as Dr. Carol Marcus, Kirk’s love interest and the newest member of the Enterprise crew, in the new Star Trek hit "Into Darkness." Before Star Trek, she was already warming her way to nerd hearts everywhere with the female lead role in the romantic comedy film "She's Out of My League". -

John Rakich Rakich Productions Inc

John Rakich Rakich Productions Inc. 809-716 The West Mall Toronto, Ontario M9C 4X6 Tel: (416) 737-7616 Email: [email protected] Website: www.johnrakich.com Affiliations Directors Guild of Canada – Ontario District Council Location Managers Guild International Academy of Canadian Cinema & Television Experience (Director / Showrunner / Producer) 2019 GRAND ARMY S1 (Joshua Donen/Chris Hatcher) Location Manager 2019 JUPITER’S LEGACY S1 (Steven S DeKnight/Steve Wakefield) Location Scout (Pre-Production) 2018 THE OCTOBER FACTION (S1) (Damian Kindler / John Calvert) Location Manager 2018 WRONG TURN (Mike Nelson / Robert Kulzer) Location Scout (Pre-Production) 2018 NO SLEEP TIL CHRISTMAS (Brent Shields/Cameron Johann/Mary Pantelidis) Location Manager 2017 SHADOWHUNTERS (S3) (Todd Slavkin/Matt Hastings/Chris Hatcher) Location Manager 2017 ANGRY ANGEL (John Ryan) Location Scout 2017 FAHRENHEIT 451 (Ramin Bahrani / David Coatsworth) Location Scout 2017 PACIFIC RIM: UPRISING (Steven S DeKnight / Jennifer Conroy) Location Consultant (Pre-Production) 2016 SALVATION (S1: EP1) (Rob Ortiz) Location Scout (Pre-Production) 2016 THE PARTING GLASS (Stephen Moyer/Cerise Hallam Larkin) Location Scout 2016 SHADOWHUNTERS (S2) (Todd Slavkin/Matt Hastings/Chris Hatcher) Location Manager 2016 THE EXPANSE (S2) (Naren Shankar / Lynn Raynor) Location Manager 2016 AMERICAN GODS (S1: EP 1-3) (David Slade / Bryan Fuller) Location Scout 2015 THE DARK TOWER (Nikolaj Arcel/ G Mac Brown) Location Scout (Pre-Production) 2015 SHIMMER LAKE (Oren Uziel / Adam Saunders) Location -

Commercials Issueissue

May 1997 • MAGAZINE • Vol. 2 No. 2 CommercialsCommercials IssueIssue Profiles of: Acme Filmworks Blue Sky Studios PGA Karl Cohen on (Colossal)Õs Life After Chapter 11 Gunnar Str¿mÕs Fumes From The Fjords An Interview With AardmanÕs Peter Lord Table of Contents 3 Words From the Publisher A few changes 'round here. 5 Editor’s Notebook 6 Letters to the Editor QAS responds to the ASIFA Canada/Ottawa Festival discussion. 9 Acme Filmworks:The Independent's Commercial Studio Marcy Gardner explores the vision and diverse talents of this unique collective production company. 13 (Colossal) Pictures Proves There is Life After Chapter 11 Karl Cohen chronicles the saga of San Francisco's (Colossal) Pictures. 18 Ray Tracing With Blue Sky Studios Susan Ohmer profiles one of the leading edge computer animation studios working in the U.S. 21 Fumes From the Fjords Gunnar Strøm investigates the history behind pre-WWII Norwegian animated cigarette commercials. 25 The PGA Connection Gene Walz offers a look back at Canadian commercial studio Phillips, Gutkin and Associates. 28 Making the Cel:Women in Commercials Bonita Versh profiles some of the commercial industry's leading female animation directors. 31 An Interview With Peter Lord Wendy Jackson talks with co-founder and award winning director of Aardman Animation Studio. Festivals, Events: 1997 37 Cartoons on the Bay Giannalberto Bendazzi reports on the second annual gathering in Amalfi. 40 The World Animation Celebration The return of Los Angeles' only animation festival was bigger than ever. 43 The Hong Kong Film Festival Gigi Hu screens animation in Hong Kong on the dawn of a new era. -

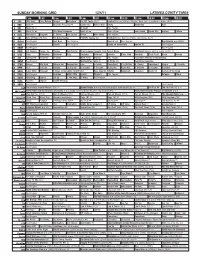

Sunday Morning Grid 12/4/11 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/4/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face/Nation Danger Horseland The NFL Today (N) Å Football Raiders at Miami Dolphins. From Sun Life Stadium in Miami. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Willa’s Wild Skiing Swimming Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour News (N) Å News (N) Å Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Explore Culture 9 KCAL Tomorrow’s Kingdom K. Shook Joel Osteen Prince Mike Webb Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Denver Broncos at Minnesota Vikings. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program Bee Season ›› (2005) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Classic Gospel Special: Tent Revival Home Prohibition Groups push to outlaw alcohol. Å 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Roadtrip Chefs Field Pépin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Al Punto (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. -

Analysis of Changes in Basic Cable TV Programming Costs

Analysis of Changes in Basic Cable TV Programming Costs Prepared by: Robert Gessner President Massillon Cable TV, Inc. Massillon, OH Phone: 330-833-5509 Email: [email protected] November 5, 2013 1 Analysis of Changes in Basic Cable TV Programming Costs It is important to note that all of this information is specific to MCTV. Our costs are unique to the extent that we offer our customers a set of networks and channels that differs from others. We also may have different costs for program content due to different outcomes of negotiations. However, I am confident you will find that the facts presented are an accurate representation of the current costs of Basic Cable TV programming, the increase in costs expected in 2014 and the rest of this decade for any independent cable TV company in the US. I believe any other cable TV company will report similar increases in cost, contract terms and conditions, and expectations for the future. 2 Analysis of Changes in Basic Cable TV Programming Costs Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 4 Expect Large Increases ............................................................................................... 4 There Are No “Local” TV Stations in NE Ohio ............................................................. 4 Seven Major Media Companies Control US TV ........................................................... 4 Contracts Are Becoming More Restrictive .................................................................. -

CHRISTOPHER LEPS Kick the Can (Spec Ad) Director, Stunt Coordinator Alex Madison, Producer

FEATURE Spaceman Stunt Coordinator Stephen Nemeth, Producer Dance Camp Stunt Coordinator Jon M. Chu, Producer Book of Swords Stunt Coordinator Wayne Kennedy, Producer Torque Fight Coordinator (uncredited) Neal H. Moritz, Producer The Waiters 2nd Unit Director Kipp Tribble, Producer Clutch Stunt Coordinator Robert Stio, Producer TELEVISION Greenleaf (1 ep.) Cover Coordinator Al Dickerson, Producer RocketJump: The Show (1 ep.) Stunt Coordinator Freddie Wong, Producer Complications (2 eps.) Cover Coordinator Craig Siebels, Producer Burger King Star Wars commercial Fight Coordinator John Landis, Director Angel (1 ep.) Asst. Sword Coordinator Skip Schoolnik, Producer Worst Case Scenarios (1 ep.) Stunt Co-Coordinator Craig Piligian, Producer Mortal Kombat Conquest (14 eps.) Asst. Fight Coordinator (uncredited) Larry Kasanoff, Producer Out of the Blue Stunt Coordinator Sam Riddle, Producer Chase (spec ad) Director, Stunt Coordinator Alex Madison, Producer CHRISTOPHER LEPS Kick the Can (spec ad) Director, Stunt Coordinator Alex Madison, Producer DIRECTOR STUNT COORDINATOR SHORT FILM STUNTMAN Director, Producer, Writer, Editor Muse (2014) www.imdb.me/christopherleps Wholehearted (2012) www.christopherleps.com Century of Light (2011), [email protected] Ed & Vern’s Rock Store (2008) Cop Sign (2005) 818 . 618 . 5661 Shadow (2004), Saber Duel (2003) Director, Producer, Editor Testing (2015) Amy and Elliot (2009) SPECIAL SKILLS AND ABILITIES Directing | Editing | Pre-Viz | Martial Arts & Weapons (30 years) | Fight Choreography | Driving Sword Work | Mo-Cap | Reactions | High Falls | Mini-Tramp | Wire Work | Air Rams & Ratchets BIO Over the past 27 years, I’ve had a unique adventure in the TV and film industry. My diverse career started at the Walt Disney Company in 1989, but my zeal for cinema was sparked by the movies seen in my youth. -

A Partial List of Productions That Have Benefited from Our Rental Line of Silicone Babies

A partial list of productions that have benefited from our rental line of silicone babies. 7th Heaven Spelling Television Friends Warner Bros. Television All My Children ABC Daytime General Hospital ABC Daytime Amazing Babies Mike Mathis Productions Get Rich Or Die Tryin’ Paramount Pictures Annie Liebovitz Annie Liebovitz Studio Ghost Whisperer Touchstone Television August Rush Warner Bros. Gilmore Girls Warner Bros. Television The Bad Girl’s Guide Flame/Paramount Girlfriends Grammnet/Paramount Battlestar Galactica NBC Universal Television Grey’s Anatomy Touchstone Television Beverly Hills 90210 Spelling Television Half & Half SisterLee Productions Big Love HBO Entertainment Halloween 9 Broad Beach Films, Inc. Bones 20th Century Fox Television Harper’s Bazaar North Six Boston Legal David E. Kelley Productions The Heartbreak Kid Radar Pictures/DreamWorks Brothers & Sisters Touchstone Television Heroes NBC Universal Television Close To Home Warner Bros. Television Hewlett Packard Tyree Productions Cold Case Warner Bros. Television Holby City BBC Television Comanche Moon Merlot Films House NBC Universal Television Crossing Jordan NBC Universal Television Inconceivable Touchstone Television Days Of Our Lives Corday/Sony Television Integris Medical AFI/Filmworks, Inc. Desperate Housewives Touchstone Television Invasion Warner Bros. Television Dharma & Greg 20th Century Fox Television The Island Dreamworks Productions Diesel P.H. Design, LLC Jake In Progress 20th Century Fox Television DIY Births BBC Television Jericho Paramount Television The Drew Carey Show Warner Bros. Television Joan of Arcadia CBS/Sony Television Drive Touchstone Television Journeyman 20th Century Fox Television Eastenders BBC Television Judging Amy CBS/20th Century Fox Enterprise Paramount Television Justice Warner Bros. Television ER Amblin/Warner Bros. The King Of Queens Paramount Television A partial list of productions that have benefited from our rental line of silicone babies. -

Richard J. Ramirez, Jr

Richard J. Ramirez, Jr. Production Designer / Art Director (Local 800) 25755 North Perlman Place, Unit B [email protected] (661) 799-0807 (Home) Stevenson Ranch, California 91381 www.tvartguy.com (661) 310-5800 (Cell) PRODUCTION DESIGNER / ART DIRECTOR Switched At Birth – 3rd, 4th, & 5th seasons (2013-2016, single-camera, long form) PRODUCTION DESIGNER Freeform (ABC Family) / Prodco, Inc. (Permanent Sets & 30 episodes) Lizzy Weiss, Paul Stupin, Exec. Producers / Shawn Wilt, Co-Exec.Producer Switched At Birth – 1st & 2nd seasons (2011-2013, single-camera, long form) ART DIRECTOR ABC Family / Prodco, Inc. (Production Designer: Greg Grande) Lizzy Weiss, Paul Stupin, Exec. Producers / Shawn Wilt, Producer Back in the Game – Pilot – (2013, single-camera, half-hour,) ART DIRECTOR FOX Television / ABC (Production Designer: Greg Grande) Make It Or Break It – 3rd season (2011-2012, single-camera, long form, HD) ART DIRECTOR ABC Family / Prodco, Inc. (Production Designer: Greg Grande) Holly Sorensen, Paul Stupin, Exec. Producers / Maria Melograne, Producer Jane by Design – 1st season (2011-2012, single-camera, long form, HD) ART DIRECTOR ABC Family / Prodco, Inc. (Production Designer: Greg Grande) April Blair, Gavin Palone, Exec. Producers / Michael Cedar, Producer CSI:NY – 2nd to 7th seasons (2005-2011, single-camera, long form, film/HD) ART DIRECTOR CBS Productions / Alliance Atlantis / Bruckheimer Films (Production Designer: Vaughan Edwards) Pam Veasey, Exec. Producer / Vikki Williams, Producer Silver Lake – Pilot (2004, single-camera, long form, film) ASSISTANT ART DIRECTOR Granite Productions / Spelling Television / UPN (Production Designer: Sandy Veneziano) Good Girls Don’t – 1st season (2004, single-camera, half-hour, 24p) ART DIRECTOR Carsey-Werner-Mandabach, LLC / Oxygen – Emily Wolf, Producer (Production Designer: Garvin Eddy) Coupling – Pilot & 1st season (2003, multi-camera, 24p) ART DIRECTOR ** Universal Network Television / NBC Studios – Michael Stokes, Producer (Production Designer: Tho. -

Stop Motion & Motion Capture Stop Motion

VolVol 22 IssueIssue 1111 February 1998 Stop Motion & Motion Capture The Politics of Performance Animation FoamFoam PuppetPuppet FrabicationFrabication ExplainedExplained BarryBarry Purves Purves ThrowsThrows DownDown thethe GauntletGauntlet Little Big Estonia InsideInside MedialabMedialab Table of Contents February, 1998 Vol. 2, No. 11 4 Editor’s Notebook Animation and its many changing faces... 5 Letters: [email protected] STOP-MOTION & MOTION-CAPTURE 6 Who’s Data Is That Anyway? Gregory Peter Panos, founding co-director of the Performance Animation Society, describes a new fron- tier of dilemmas, the politics of performance animation. 9 Boldly Throwing Down the Gauntlet In our premier issue, acclaimed stop-motion animator Barry J.C. Purves shared his sentiments on the coming of the computer. Now Barry’s back to share his thoughts on the last two years that have been both exhilarating and disappointing for him. 14 A Conversation With... In a small, quiet cafe, motion-capture pioneer Chris Walker and outrageous stop-motion animator Corky Quakenbush got together for lunch and discovered that even though their techniques may appear to be night and day, they actually have a lot in common. 21 At Last, Foam Puppet Fabrication Explained! How does one build an armature from scratch and end up with a professional foam puppet? Tom Brierton is here to take us through the steps and offer advice. 27 Little Big Estonia:The Nukufilm Studio On the 40th anniversary of Estonia’s Nukufilm, Heikki Jokinen went for a visit to profile the puppet ani- mation studio and their place in the post-Soviet world. 31 Wallace & Gromit Spur Worldwide Licensing Activity Karen Raugust takes a look at the marketing machine behind everyone’s favorite clay characters, Wallace & Gromit. -

Cartoons Cartoons Are Arranged by Character Or Series Or Studio

Public Domain Cartoons Cartoons are arranged by character or series or studio. Betty Boop Cartoons: Each are 7 minutes long Disc #1: Betty Boop’s Crazy Inventions (1933) Directed by Dave Fleischer House Cleaning Blues (1937) Directed by Dave Fleischer Poor Cinderella (Color, 1934) Directed by Dave Fleischer Betty Boop’s Rise to Fame (1934) Directed by Dave Fleischer Betty in Blunderland (1934) Directed by Dave Fleischer More Pep (1936) Directed by Dave Fleischer Is My Palm Red? (1933) Directed by Dave Fleischer Betty Boop’s Ker-Choo (1933) Directed by Dave Fleischer Betty Boop with Henry (1935) Directed by Dave Fleischer Be Human (1936) Directed by Dave Fleischer Judge for a Day (1935) Directed by Dave Fleischer Betty Boop and Little Jimmy (1936) Directed by Dave Fleischer No, No, A Thousand Times No (1935) Directed by Dave Fleischer Betty Boop and the Little King (1936) Directed by Dave Fleischer Hot Air Salesman (1937) Directed by Dave Fleischer Stop That Noise (1935) Directed by Dave Fleischer Musical Mountaineers (1939) Directed by Dave Fleischer Betty Boop, Disc #2: Betty Boop and Grampy (1935) Directed by Dave Fleischer Grampy’s Indoor Outing (1936) Directed by Dave Fleischer The Impractical Joker (1937) Directed by Dave Fleischer On With the New (1938) Directed by Dave Fleischer So Does An Automobile (1939) Directed by Dave Fleischer Whoops, I’m a Cowboy (1937) Directed by Dave Fleischer Taking the Blame (1935) Directed by Dave Fleischer Swat the Fly (1935) Directed by Dave Fleischer Little Nobody (1936) Directed by Dave Fleischer