Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior 180 (2019) 52–59

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belviq® (Lorcaserin) Patient Information

Belviq® (lorcaserin) Patient Information Who Is Belviq For? Belviq is a medication for chronic weight management. It is for people with overweight and weight-related conditions or obesity. It is meant to be used together with a lifestyle therapy regimen involving a reduced calorie diet and increased physical activity. How Does Belviq Work? Belviq works in the brain as an appetite suppressant. Who Should Not Take Belviq? Women who are pregnant, nursing, or planning to become pregnant. How Is Belviq Dosed? Belviq® (lorcaserin) Belviq XR® (lorcaserin extended release) Take one 10 mg tablet 2 times each day with Take one 20 mg tablet once daily with or or without food. without food. Is Belviq a Controlled Substance? Belviq is a federally controlled substance because it contains lorcaserin hydrochloride and may be abused or lead to drug dependence. Some states do not allow your doctor to prescribe more than one month at a time. Which Medications Might Not Be Safe to Use with Belviq? Belviq can affect how other medicines work in your body, and other medicines can affect how Belviq works. Tell your doctor about all the medicines and supplements you take, especially those used to treat depression, migraines, or other medical conditions, such as: • Triptans—used to treat migraine headache • Medicines used to treat mood, anxiety, psychotic or thought disorders, including tricyclics, lithium, selective serotonin uptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin- norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), or antipsychotics • Cabergoline—used to treat a hormone imbalance involving prolactin • Linezolid—an antibiotic • Tramadol—an opioid pain reliever • Dextromethorphan—an over-the-counter medicine used to treat the common cold or cough • Over-the-counter supplements such as tryptophan or St. -

The Melanocortin-4 Receptor As Target for Obesity Treatment: a Systematic Review of Emerging Pharmacological Therapeutic Options

International Journal of Obesity (2014) 38, 163–169 & 2014 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0307-0565/14 www.nature.com/ijo REVIEW The melanocortin-4 receptor as target for obesity treatment: a systematic review of emerging pharmacological therapeutic options L Fani1,3, S Bak1,3, P Delhanty2, EFC van Rossum2 and ELT van den Akker1 Obesity is one of the greatest public health challenges of the 21st century. Obesity is currently responsible for B0.7–2.8% of a country’s health costs worldwide. Treatment is often not effective because weight regulation is complex. Appetite and energy control are regulated in the brain. Melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) has a central role in this regulation. MC4R defects lead to a severe clinical phenotype with lack of satiety and early-onset severe obesity. Preclinical research has been carried out to understand the mechanism of MC4R regulation and possible effectors. The objective of this study is to systematically review the literature for emerging pharmacological obesity treatment options. A systematic literature search was performed in PubMed and Embase for articles published until June 2012. The search resulted in 664 papers matching the search terms, of which 15 papers remained after elimination, based on the specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. In these 15 papers, different MC4R agonists were studied in vivo in animal and human studies. Almost all studies are in the preclinical phase. There are currently no effective clinical treatments for MC4R-deficient obese patients, although MC4R agonists are being developed and are entering phase I and II trials. International Journal of Obesity (2014) 38, 163–169; doi:10.1038/ijo.2013.80; published online 18 June 2013 Keywords: MC4R; treatment; pharmacological; drug INTRODUCTION appetite by expressing anorexigenic polypeptides such as Controlling the global epidemic of obesity is one of today’s pro-opiomelanocortin and cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated most important public health challenges. -

Introduced B.,Byhansen, 16

LB301 LB301 2021 2021 LEGISLATURE OF NEBRASKA ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH LEGISLATURE FIRST SESSION LEGISLATIVE BILL 301 Introduced by Hansen, B., 16. Read first time January 12, 2021 Committee: Judiciary 1 A BILL FOR AN ACT relating to the Uniform Controlled Substances Act; to 2 amend sections 28-401, 28-405, and 28-416, Revised Statutes 3 Cumulative Supplement, 2020; to redefine terms; to change drug 4 schedules and adopt federal drug provisions; to change a penalty 5 provision; and to repeal the original sections. 6 Be it enacted by the people of the State of Nebraska, -1- LB301 LB301 2021 2021 1 Section 1. Section 28-401, Revised Statutes Cumulative Supplement, 2 2020, is amended to read: 3 28-401 As used in the Uniform Controlled Substances Act, unless the 4 context otherwise requires: 5 (1) Administer means to directly apply a controlled substance by 6 injection, inhalation, ingestion, or any other means to the body of a 7 patient or research subject; 8 (2) Agent means an authorized person who acts on behalf of or at the 9 direction of another person but does not include a common or contract 10 carrier, public warehouse keeper, or employee of a carrier or warehouse 11 keeper; 12 (3) Administration means the Drug Enforcement Administration of the 13 United States Department of Justice; 14 (4) Controlled substance means a drug, biological, substance, or 15 immediate precursor in Schedules I through V of section 28-405. 16 Controlled substance does not include distilled spirits, wine, malt 17 beverages, tobacco, hemp, or any nonnarcotic substance if such substance 18 may, under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 U.S.C. -

Nanotechnology‐Mediated Drug Delivery for the Treatment Of

REVIEW Obesity www.advhealthmat.de Nanotechnology-Mediated Drug Delivery for the Treatment of Obesity and Its Related Comorbidities Yung-Hao Tsou, Bin Wang, William Ho, Bin Hu, Pei Tang, Sydney Sweet, Xue-Qing Zhang,* and Xiaoyang Xu* crisis globally. People with a body mass Obesity is a serious health issue affecting humanity on a global scale. index (BMI, mass in kilograms divided by Recognized by the American Medical Association as a chronic disease, the the square of the height in meters) above −2 [3,4] incidence of obesity continues to grow at an accelerating rate and obesity 30 kg m are considered obese. The American Medical Association has classi- has become one of the major threats to human health. Excessive weight fied obesity as a reversible and preventable gain is tied to metabolic syndrome, which is shown to increase the risk chronic disease, which is accompanied of chronic diseases, such as heart disease and type 2 diabetes, taxing an by a host of related deadly comorbidities already overburdened healthcare system and increasing mortality worldwide. including type 2 diabetes, heart disease, [5] Available treatments such as bariatric surgery and pharmacotherapy are and several types of cancers. Particularly, often accompanied by adverse side effects and poor patient compliance. diabetic disorders and cardiovascular dis- eases are the most common comorbidities Nanotechnology, an emerging technology with a wide range of biomedical associated with obesity. applications, has provided an unprecedented opportunity to improve The causes of obesity are complex and the treatment of many diseases, including obesity. This review provides multivariate. Broadly speaking, behavior an introduction to obesity and obesity-related comorbidities. -

Repeated 7-Day Treatment with the 5-HT2C Agonist Lorcaserin

Neuropsychopharmacology (2017) 42, 1082–1092 © 2017 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/17 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Repeated 7-Day Treatment with the 5-HT2C Agonist Lorcaserin or the 5-HT2A Antagonist Pimavanserin Alone or in Combination Fails to Reduce Cocaine vs Food Choice in Male Rhesus Monkeys ,1 1 Matthew L Banks* and S Stevens Negus 1 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA Cocaine use disorder is a global public health problem for which there are no Food and Drug Administration-approved pharmacotherapies. Emerging preclinical evidence has implicated both serotonin (5-HT) 2C and 2A receptors as potential mechanisms for mediating serotonergic attenuation of cocaine abuse-related neurochemical and behavioral effects. Therefore, the present study aim – – was to determine whether repeated 7-day treatment with the 5-HT2C agonist lorcaserin (0.1 1.0 mg/kg per day, intramuscular; 0.032 – 0.1 mg/kg/h, intravenous) or the 5-HT2A inverse agonist/antagonist pimavanserin (0.32 10 mg/kg per day, intramuscular) attenuated cocaine reinforcement under a concurrent ‘choice’ schedule of cocaine and food availability in rhesus monkeys. During saline treatment, cocaine maintained a dose-dependent increase in cocaine vs food choice. Repeated pimavanserin (3.2 mg/kg per day) treatments significantly increased small unit cocaine dose choice. Larger lorcaserin (1.0 mg/kg per day and 0.1 mg/kg/h) and pimavanserin (10 mg/kg per day) doses primarily decreased rates of operant behavior. Coadministration of ineffective lorcaserin (0.1 mg/kg per day) and pimavanserin (0.32 mg/kg per day) doses also failed to significantly alter cocaine choice. -

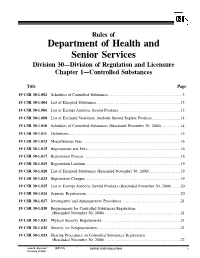

19 CSR 30-1.042 Inventory Requirements

Rules of Department of Health and Senior Services Division 30—Division of Regulation and Licensure Chapter 1—Controlled Substances Title Page 19 CSR 30-1.002 Schedules of Controlled Substances .........................................................3 19 CSR 30-1.004 List of Excepted Substances.................................................................13 19 CSR 30-1.006 List of Exempt Anabolic Steroid Products................................................13 19 CSR 30-1.008 List of Excluded Veterinary Anabolic Steroid Implant Products......................14 19 CSR 30-1.010 Schedules of Controlled Substances (Rescinded November 30, 2000)...............14 19 CSR 30-1.011 Definitions......................................................................................15 19 CSR 30-1.013 Miscellaneous Fees ...........................................................................16 19 CSR 30-1.015 Registrations and Fees........................................................................16 19 CSR 30-1.017 Registration Process ..........................................................................16 19 CSR 30-1.019 Registration Location.........................................................................19 19 CSR 30-1.020 List of Excepted Substances (Rescinded November 30, 2000)........................19 19 CSR 30-1.023 Registration Changes .........................................................................19 19 CSR 30-1.025 List of Exempt Anabolic Steroid Products (Rescinded November 30, 2000).......20 19 CSR 30-1.026 -

022529Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 022529Orig1s000 OTHER REVIEW(S) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- This is a representation of an electronic record that was signed electronically and this page is the manifestation of the electronic signature. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- /s/ ---------------------------------------------------- AMY M TAYLOR 06/26/2012 LISA L MATHIS 06/28/2012 Reference ID: 3145988 Division of Metabolism and Endocrinology Products REGULATORY PROJECT MANAGER LABELING REVIEW Application: NDA 022529 Name of Drug: Belviq (lorcaserin hydrochloride) tablets, 10 mg Applicant: Arena Pharmaceuticals Labeling Submission Date: May 23, 2012 Receipt Date: May 24, 2012 Background and Summary Description: Belviq (lorcaserin hydrochloride) is a new molecular entity that is a 5-hydroxytryptamine 2C (5HT2C) receptor agonist affecting those receptors in the appetite center of the brain. The indication is as an adjunct to diet and exercise for weight management, including weight loss and maintenance, in obese patients with an initial body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2, or in 2 overweight patients with a body mass index greater than or equal to 27 kg/m in the presence of at least one weight-related comorbid condition (e.g., hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, glucose intolerance, sleep apnea, type 2 diabetes). The NDA was originally submitted on December -

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2020 By

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2020 By: Senator(s) Jordan, Jackson (11th) To: Drug Policy; Judiciary, Division A SENATE BILL NO. 2694 1 AN ACT TO AMEND SECTION 41-29-113, MISSISSIPPI CODE OF 1972, 2 TO ADD FLUALPRAZOLAM, FLUBROMAZEPAM, FLUBROMAZOLAM AND CLONAZOLAM 3 TO SCHEDULE I BECAUSE THESE DRUGS HAVE NO LEGITIMATE MEDICAL USE 4 AND HAVE HIGH POTENCY WITH GREAT POTENTIAL TO CAUSE HARM; TO AMEND 5 SECTION 41-29-115, MISSISSIPPI CODE OF 1972, TO REVISE SCHEDULE II 6 TO CLARIFY THE CHEMICAL NAME OF THIAFENTANIL; TO AMEND SECTION 7 41-29-119, MISSISSIPPI CODE OF 1972, TO ADD TO SCHEDULE IV THE 8 DRUGS BREXANOLONE (ZULRESSO) AND SOLRIAMFETOL (SUNOSI) BECAUSE 9 THESE DRUGS RECENTLY HAVE BEEN APPROVED FOR MEDICAL USE BY THE 10 FEDERAL DRUG ADMINISTRATION; AND FOR RELATED PURPOSES. 11 BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI: 12 SECTION 1. Section 41-29-113, Mississippi Code of 1972, is 13 amended as follows: 14 41-29-113. 15 SCHEDULE I 16 (a) Schedule I consists of the drugs and other substances, 17 by whatever official name, common or usual name, chemical name, or 18 brand name designated, that is listed in this section. 19 (b) Opiates. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed 20 in another schedule, any of the following opiates, including their 21 isomers, esters, ethers, salts and salts of isomers, esters and S. B. No. 2694 *SS08/R210* ~ OFFICIAL ~ G1/2 20/SS08/R210 PAGE 1 (csq\tb) 22 ethers, whenever the existence of these isomers, esters, ethers 23 and salts is possible within the specific chemical designation: -

Laws 2021, LB236, § 4

LB236 LB236 2021 2021 LEGISLATIVE BILL 236 Approved by the Governor May 26, 2021 Introduced by Brewer, 43; Clements, 2; Erdman, 47; Slama, 1; Lindstrom, 18; Murman, 38; Halloran, 33; Hansen, B., 16; McDonnell, 5; Briese, 41; Lowe, 37; Groene, 42; Sanders, 45; Bostelman, 23; Albrecht, 17; Dorn, 30; Linehan, 39; Friesen, 34; Aguilar, 35; Gragert, 40; Kolterman, 24; Williams, 36; Brandt, 32. A BILL FOR AN ACT relating to law; to amend sections 28-1202 and 69-2436, Reissue Revised Statutes of Nebraska, and sections 28-401 and 28-405, Revised Statutes Cumulative Supplement, 2020; to redefine terms, change drug schedules, and adopt federal drug provisions under the Uniform Controlled Substances Act; to provide an exception to the offense of carrying a concealed weapon as prescribed; to define a term; to change provisions relating to renewal of a permit to carry a concealed handgun; to provide a duty for the Nebraska State Patrol; to eliminate an obsolete provision; to harmonize provisions; and to repeal the original sections. Be it enacted by the people of the State of Nebraska, Section 1. Section 28-401, Revised Statutes Cumulative Supplement, 2020, is amended to read: 28-401 As used in the Uniform Controlled Substances Act, unless the context otherwise requires: (1) Administer means to directly apply a controlled substance by injection, inhalation, ingestion, or any other means to the body of a patient or research subject; (2) Agent means an authorized person who acts on behalf of or at the direction of another person but does not include a common or contract carrier, public warehouse keeper, or employee of a carrier or warehouse keeper; (3) Administration means the Drug Enforcement Administration of the United States Department of Justice; (4) Controlled substance means a drug, biological, substance, or immediate precursor in Schedules I through V of section 28-405. -

Belviq, Belviq XR) Reference Number: CP.PCH.03 Effective Date: 05.01.17 Last Review Date: 08.20 Line of Business: Commercial, HIM* Revision Log

Clinical Policy: Lorcaserin (Belviq, Belviq XR) Reference Number: CP.PCH.03 Effective Date: 05.01.17 Last Review Date: 08.20 Line of Business: Commercial, HIM* Revision Log See Important Reminder at the end of this policy for important regulatory and legal information. Description Lorcaserin (Belviq®, Belviq XR®) is a serotonin 2C receptor agonist. FDA Approved Indication(s)* Belviq and Belviq XR are indicated as an adjunct to a reduced-calorie diet and increased physical activity for chronic weight management in adult patients with an initial body mass index (BMI) of: • 30 kg/m2 or greater (obese), or • 27 kg/m2 or greater (overweight) in the presence of at least one weight-related comorbidity such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, or dyslipidemia. Limitation(s) of use: • The safety and efficacy of coadministration of Belviq/Belviq XR with other products intended for weight loss including prescription drugs (e.g., phentermine), over-the-counter drugs, and herbal preparations have not been established. • The effect of Belviq/Belviq XR on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality has not been established. ____________ *Eisai Co., Ltd, manufacturer of Belviq, was asked by the FDA to voluntarily withdraw Belviq after a post- market safety trial found an increase occurrence of cancer reported in people who used the product (see Appendix E). Policy/Criteria Provider must submit documentation (such as office chart notes, lab results or other clinical information) supporting that member has met all approval criteria. It is the policy of health plans affiliated with Centene Corporation® that Belviq and Belviq XR are medically necessary when the following criteria are met: I. -

Lorcaserin for the Treatment of Obesity? a Closer Look at Its Side Effects

Editorial Open Heart: first published as 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000173 on 19 October 2014. Downloaded from Lorcaserin for the treatment of obesity? A closer look at its side effects James J DiNicolantonio,1 Subhankar Chatterjee,2 James H O’Keefe,1 Pascal Meier3,4 To cite: DiNicolantonio JJ, fi Obesity is developing into a pandemic in higher af nity for 5-HT2C than for 5-HT2A ’ – Chatterjee S, O Keefe JH, countries like the USA, the UK and India.1 3 receptors and 100 times higher selectivity for et al. Lorcaserin for the 13–15 treatment of obesity? A The WHO projects that by 2015, about 700 5-HT2C than for the 5-HT2B receptors. 4 closer look at its side effects. million adults will be clinically obese. It has achieved a clinically meaningful weight Open Heart 2014;1:e000173. Obesity is a major public health problem, loss as per Food and Drug Administration’s doi:10.1136/openhrt-2014- beyond the disability directly related to exces- (FDA’s) guidance criteria (2007), that is, 000173 sive adiposity, and it also increases the risk of a mean efficacy criterion (a medication- several chronic diseases such as hyperten- associated (ie, greater than placebo) weight sion, sleep apnoea, diabetes, coronary artery reduction of 5%) and a categorical efficacy fi Accepted 1 October 2014 disease and cancer. Clearly, obesity is a criterion (a signi cantly greater proportion serious threat, imposing a vast economic (at least 35%) of those individuals receiving burden on the healthcare system.5 the medication compared with placebo con- Obesity is the second most -

Serotonin Receptors and Drugs Affecting Serotonergic Neurotransmission R ICHARD A

Chapter 11 Serotonin Receptors and Drugs Affecting Serotonergic Neurotransmission R ICHARD A. GLENNON AND MAŁGORZATA DUKAT Drugs Covered in This Chapter* Antiemetic drugs (5-HT3 receptor • Rizatriptan • Imipramine antagonists) • Sumatriptan • Olanzapine • Alosetron • Zolmitriptan • Propranolol • Dolasetron Drug for the treatment of • Quetiapine • Granisetron irritable bowel syndrome (5-HT4 • Risperidone • Ondansetron agonists) • Tranylcypromine • Palonosetron • Tegaserod • Trazodone • Tropisetron Drugs for the treatment of • Ziprasidone Drugs for the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders • Zotepine migraine (5-HT1D/1F receptor agonists) • Buspirone Hallucinogenic agents • Almotriptan • Citalopram • Lysergic acid diethylamide • Eletriptan • Clozapine • 2,5-dimethyl-4-bromoamphetamine • Frovatriptan • Desipramine • 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine • Naratriptan • Fluoxetine Abbreviations cAMP, cyclic adenosine IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with nM, nanomoles/L monophosphate constipation MT, melatonin CNS, central nervous system IBS-D, irritable bowel syndrome with MTR, melatonin receptor 5-CT, 5-carboxamidotryptamine diarrhea NET, norepinephrine reuptake transporter DOB, 2,5-dimethyl-4-bromoamphetamine LCAP, long-chain arylpiperazine 8-OH DPAT, 8-hydroxy-2-(di-n- DOI, 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine L-DOPA, L-dihydroxyphenylalanine propylamino)tetralin EMDT, 2-ethyl-5-methoxy-N,N- LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide PMDT, 2-phenyl-5-methoxy-N,N- dimethyltryptamine MAO, monomaine oxidase dimethyltryptamine GABA, g-aminobutyric acid MAOI,