Atomic Age and the Rise of Mutually Assured Destruction. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tom Fleischman CAS

Career Achievement Award Recipient Tom Fleischman CAS CAS Award Nominees Production Equipment FOMO How the CAS Started Remembering Jim Alexander WINTER 2020 CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARDS NOMINEE OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENT IN SOUND MIXING MPSE GOLDEN REEL AWARDS NOMINEE FEATURE - ADR/DIALOGUE PHILIP STOCKTON, MPSE, EUGENE GEARTY, MARISSA LITTLEFIELD “EXQUISITELY MADE, EVERY DETAIL CAREFULLY CONSIDERED. IT FEELS UTTERLY TRANSPORTING.” NETFLIXGUILDS.COM CAS QUARTERLY, COVER 2 NETFLIX: THE IRISHMAN PUB DATE 12/30/19 BLEED: 8.625” X 11.125” TRIM: 8.375” X 10.875” CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARDS NOMINEE OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENT IN SOUND MIXING MPSE GOLDEN REEL AWARDS NOMINEE FEATURES FEATURE - ADR/DIALOGUE Production Sound Equipment Purchases . 20 PHILIP STOCKTON, MPSE, EUGENE GEARTY, MARISSA LITTLEFIELD Ever have a “Fear of Missing Out”? 147th AES Convention . 26 Career Achievement Recipient . 34 Re-recording mixer Tom Fleischman CAS CAS Filmmaker Award . 44 34 Director, producer, and writer James Mangold CAS Award Nominations . 46 Outstanding Product Nominees . 50 Student Recognition Award Finalists . 52 The Start of the CAS . 54 Bob Hoyt had a vision A Case Study in Multilanguage Production Sound . 60 Possession 54 The “Sound” of Genre Storytelling . 64 Mixing approaches infl uenced by genre Remembering a Legend . 68 Production sound mixer Jim Alexander “EXQUISITELY MADE, DEPARTMENTS EVERY DETAIL The President’s Letter . 4 From the Editor . 6 CAREFULLY CONSIDERED. 60 Collaborators . 9 Meet the people behind the words IT FEELS UTTERLY Technically Speaking -

Air Force Enlisted Personnel Policy 1907-1956

FOUNDATION of the FORCE Air Force Enlisted Personnel Policy 1907-1956 Mark R. Grandstaff DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A Approved for Public Release Distribution Unlimited AIR PROGRAM 1997 20050429 034 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Grandstaff, Mark R. Foundation of the Force: Air Force enlisted personnel policy, 1907-1956 / Mark R. Grandstaff. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. United States. Air Force-Non-commissioned officers-History. 2. United States. Air Force-Personnel management-History. I. Title. UG823.G75 1996 96-33468 358.4'1338'0973-DC20 CIP For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-9328 ISBN 0-16-049041-3 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGEFomApve OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information Is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of Information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. -

WV Graded Music List 2011

2011 WV Graded Music List, p. 1 2011 West Virginia Graded Music List Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3 Grade 4 Grade 5 Grade 6 Grade Artist Arranger Title Publisher 1 - Higgins, John Suo Gan HL 1 - McGinty Japanese Folk Trilogy QU 1 - McGinty, Anne Elizabethan Songbook, An KJ 1 - Navarre, Randy Ngiele, Ngiele NMP 1 - Ployhar Along the Western Trail BE 1 - Ployhar Minka BE 1 - Ployhar Volga Boat Song BE 1 - Smith, R.W. Appalachian Overture BE Variant on an Old English 1 - Smith, R.W. BE Carol 1 - Story A Jubilant Carol BE 1 - Story Classic Bits and Pieces BE 1 - Story Patriotic Bits and Pieces BE 1 - Swearingen Three Chorales for Band BE 1 - Sweeney Shenandoah HL 1 Adams Valse Petite SP 1 Akers Berkshire Hills BO 1 Akers Little Classic Suite CF 1 Aleicheim Schaffer Israeli Folk Songs PO 1 Anderson Ford Forgotten Dreams BE 1 Anderson Ford Sandpaper Ballet BE 1 Arcadelt Whiting Ave Maria EM 1 Arensky Powell The Cuckoo PO 1 Bach Gardner Little Bach Suite ST Grand Finale from Cantata 1 Bach Gordon BO #207 1 Bach Walters Celebrated Air RU 1 Bain, James L. M Wagner Brother James' Air BE 1 Balent Bold Adventure WB Drummin' With Reuben And 1 Balent BE Rachel 1 Balent Lonesome Tune WB 1 Balmages Gettysburg FJ 2011 WV Graded Music List, p. 2 1 Balmages Majestica FJ 1 Barnes Ivory Towers of Xanadu SP 1 Bartok Castle Hungarian Folk Suite AL 1 Beethoven Clark Theme From Fifth Symphony HL 1 Beethoven Foulkes Creation's Hymn PO 1 Beethoven Henderson Hymn to Joy PO 1 Beethoven Mitchell Ode To Joy CF 1 Beethoven Sebesky Three Beethoven Miniatures Al 1 Beethoven Tolmage -

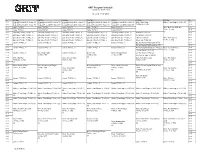

GRIT Program Schedule Listings in Eastern Time

GRIT Program Schedule Listings in Eastern Time Week Of 11-07-2016 Grit 11/7 Mon 11/8 Tue 11/9 Wed 11/10 Thu 11/11 Fri 11/12 Sat 11/13 Sun Grit 06:00A Sergeant Preston Of The Yukon: TV- Sergeant Preston Of The Yukon: TV- Sergeant Preston Of The Yukon: TV- Sergeant Preston Of The Yukon: TV- Sergeant Preston Of The Yukon: TV- Movie: Adios Amigo Walker, Texas Ranger: TV-14 V; CC 06:00A 06:30A SergeantPG V; CC Preston Of The Yukon: TV- SergeantPG V; CC Preston Of The Yukon: TV- SergeantPG V; CC Preston Of The Yukon: TV- SergeantPG V; CC Preston Of The Yukon: TV- SergeantPG V; CC Preston Of The Yukon: TV- TV-PG L, S, V; 1976 06:30A 07:00A Lassie:PG V; CC TV-PG V; Lassie:PG V; CC TV-PG V; Lassie:PG V; CC TV-PG V; Lassie:PG V; CC TV-PG V; Lassie:PG V; CC TV-PG V; Movie: Messenger Of Death 07:00A 07:30A Lassie: TV-PG V; Lassie: TV-PG V; Lassie: TV-PG V; Lassie: TV-PG V; Lassie: TV-PG V; TV-14 L, V; 1988 07:30A CC 08:00A Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; MuscleCar: TV-PG; CC 08:00A 08:30A Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Horsepower: TV-PG; CC 08:30A 09:00A Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Trucks!: TV-PG; CC Movie: Passenger 57 09:00A 09:30A Zane Grey Theatre: TV-PG L, V; Zane Grey Theatre: -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

The Daily Egyptian, May 21, 1965

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC May 1965 Daily Egyptian 1965 5-21-1965 The aiD ly Egyptian, May 21, 1965 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_May1965 Volume 46, Issue 150 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, May 21, 1965." (May 1965). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1965 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in May 1965 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~~~,~; ~·~~!)n.:D1ES 15 Chosen for Sphinx Meimber;h'tp . J)~ , - ':.",5 Fifteen students were of SIU; the Outstanding Male ~ R ,8¥erz, Laurie J. Brown, tapped for membership in the and Female Freshmen and. Jo·iI#l~ F. Wilhelm, Kathy ~!. Sphinx Club at the Honors Day Sophomores were named; and' w~Htk; and the· late F: arl 1I.like Convocation Thursday in the the University Student Council C arson (accepted by·. i\lrs. Arena. award was presented. Jananne Carson). Neariy 400 students and New members of the Sphinx Sphinx Club members from faculty members were cited Club, special interest acth'i- the Edwardsville campus in for hOlPrs for activities on ties honorary were: Richard clude Lawrence F. Ashley, EGYPTIAN campus at the convocation. L. Cox, Warren steinborn, R. Helen F. Black, Charles A. Fifteen coeds were tapped Daniel Crumbaugh, William Buchana, Roger B. Burch, SfUlltlteJUl, 9t 1Ut4i4 'Z(fIiq.,,,~ into Cap and Tassel; one facul- Murphy, Joseph K. Beer, Cheryl R. Cobbel, Daniel L. ty member was awarded the Charolette K. -

Documenting the Director: Delbert Mann, His Life, His Work, and His Papers

http://spider.georgetowncollege.edu/htallant/border/bs10/fr-harw.htm Border States: Journal of the Kentucky-Tennessee American Studies Association, No. 10 (1995) DOCUMENTING THE DIRECTOR: DELBERT MANN, HIS LIFE, HIS WORK, AND HIS PAPERS Sarah Harwell Vanderbilt University Library The Papers of Delbert Mann at the Special Collections Library of Vanderbilt University provide not only a rich chronicle of the award-winning television and motion picture director's life and work, but also document the history of aspects of American popular culture and motion picture art in the latter half of the twentieth century. Delbert Mann was born in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1920. He moved to Nashville, which he considers his home town, as a young boy when his father came to teach at Scarritt College. He graduated from Hume-Fogg High School and Vanderbilt University, where Dinah Shore and Mann's future wife, Ann Caroline Gillespie, were among his classmates. Also in Nashville he developed a lifelong friendship with Fred Coe through their mutual involvement in the Nashville Community Playhouse. Coe would play a very important role in Mann's life. A few months after his graduation from Vanderbilt in 1941, Mann joined the Eighth Air Force, for which he completed thirty-five missions as a pilot of a B-24 bomber. After the end of the Second World War he attended the Yale Drama School, followed by two years as director of the Town Theatre of Columbia, South Carolina. In 1949, Fred Coe, already a producer at NBC television network, invited Delbert Mann to come to New York to direct live television drama on the "Philco Television Playhouse." Then in its infancy, television offered many fine original plays to its relatively small viewing audience. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Tyler Beck HIS 485 Oral History: the Pilots of Plattsburgh Air Force Base

Oral History: The Pilots of Plattsburgh Air Force Base Item Type Other Authors Beck, Tyler Download date 28/09/2021 23:12:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12648/1306 Tyler Beck HIS 485 Oral History: The Pilots of Plattsburgh Air Force Base 2 Interview #1 Frank Baehre Pilot U .S. Air Force Interviewer: (Tyler Beck) Narrator (Frank Baehre Finding Aid Interview with Frank Baehre. February. 20 2014 at the Battle of Plattsburgh Museum, Plattsburgh, NY. Recorded with a smart phone. Biographical Information o Baehre was born in Buffalo, New York on September 22, 1948. He was an only child in the suburbs outside of Buffalo. His father died at a young age and his mother was left to raise him alone. He when to Cleveland Hill High School in Cheektowaga NY, where he graduated in 1966. Baehre attended SUNY Buffalo and enrolled in Air Force ROTC his freshman year. Baehre graduated from Air Force Pilot Training in Lubbock, Texas where he left to serve in Vietnam and Thailand in 1972. After his one-year tour, Baehre returned to the U.S. and joined SAC (Strategic Air Command) and was a member of the Air Force until his retirement until 1993. He is married to Sandy Baehre (1970) and he has two children. Baehre has flown a number a planes during his career including: the T-41, T-47, T-38, the AC-119K, B-52Hs, and the FB-111s. Interview Finding Aid 3 Summary of contents of interview, arranged alphabetically Air Force, U.S. Airplanes Air Force, U.S. -

The Missouri Miner, November 05, 1965

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine The Missouri Miner Newspaper Special Collections 05 Nov 1965 The Missouri Miner, November 05, 1965 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/missouri_miner These newspapers reflect the attitudes, perspectives, and beliefs of different times. Neither the library nor the university endorses the views expressed in these collections, some of which contain images and language which may be offensive to some readers. Recommended Citation "The Missouri Miner, November 05, 1965" (1965). The Missouri Miner Newspaper. 1814. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/missouri_miner/1814 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Missouri Miner Newspaper by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WELCOME FUTURE OF MISSOURI AT ROLLA ENGINEERS VoLUME 52 FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 1965, ROLLA, MISSOURI NUMBER 8 Max1uhnan Faculty Proposes Scholastic Changes IheJi/ B Ie.) ag, ays!", SfuJenf.1 Yrlj£J fo Opinionj Open House to Be Held tED TilING Reprejenfafivej this column in For Future Engineers In a series of recent IJresenta be recorded unless ex tenuating is registered, his schedule must be :en minutes. In tions before the UMR' Student circumstances are stated by the reduced to not more than 15 An invitation to visit the MSM vising and counseling for prospec gone by except Co ullcil, Professor Charles Rem department. hours. campus Nov. -

Script – Cuban Crisis Briefing Title Slide If You Were a Missile Or

Script – Cuban Crisis Briefing Title Slide If you were a missile or bomber crew member 50 years ago today, you would have been on continuous alert for the last two weeks. I say continuous because about half the crew force is on alert - the other half is resting and waiting to take their place. If you were in maintenance, munitions, security, comm or almost any other base specialty, you would be working continuous shift work. Every office, shop and work center has been manned for 24 hours each day for over two weeks - you are either working or resting. Nobody is on leave, on pass, TDY or doing nonessential tasks. We are at the brink on Nuclear War - we are in the Cuban Missile Crisis. Slide October 1962 first line The Cuban Crisis didn't happen overnight - several events over the months before led to it. In early 1961, the US CIA put together a poorly planned invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. The invasion failed, and most of the Cuban Exiles who took part were captured or killed. But the attempt really bothered Fidel Castro. He was convinced that the US would invade again soon, this time with the full might of the US military. Castro asked his friend in the Soviet Union, Nikita Krushchev, for help. Krushchev had his own concerns - he knew that the Soviet Union was ringed with US bomber bases in Europe, the Pacific and Canada, allowing US bombers to strike deep into the heartland of his country. And he knew his own bombers couldn't penetrate as deep, since they were all based within the Soviet Union. -

12 O'clock High and the Image of American Air Power, 1946-1967 Sam Edwards, Manchester Metropolitan University the Image Was P

12 O’Clock High and the Image of American Air Power, 1946-1967 Sam Edwards, Manchester Metropolitan University The image was powerful and infamous: Slim Pickens, rodeo performer and star of numerous film and television Westerns, straddles a giant H-Bomb and, with Stetson in hand, rides it to earth and to doomsday. Here was the essence of Stanley Kubrick’s film Dr. Strangelove (1964), a dark satire on the insanity of a world that could produce a doctrine of Armageddon and, without irony, reduce it to the acronym “MAD” (Mutually Assured Destruction). While provocative, Kubrick’s film was merely the “most notorious chapter in this period’s assault on the image of air power.”1 With origins in the era of interwar isolationism, and expressed via print media as well as early cinema, this image asserted that American air power provided protection, deterred potential aggressors and, if necessary, would deliver victory when war came. In the eyes of many strategists, this image was affirmed by the events and experiences of World War II, a conflict that saw American air force commanders loudly proclaim faith in the bomber’s ability to secure victory through the precise delivery of destruction. These were the ideas celebrated in wartime propaganda and, with some subtle revisions and refinements, post-war cinema, from Air Force (1943) to A Gathering of Eagles (1963). By the early 1960s, however, as Cold War tensions increased, this image came under increasing criticism—hence Dr. Strangelove. Hence, too, Joseph Heller’s novel Catch-22 (1961), adapted as a film in 1970, and John Hersey’s The War Lover (1959), released in cinemas in 1962.