Audience Reception Studies: Audience Theory and Audience Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Agenda Setting Hypothesis in the New Media Environment Las Hipótesis De La Agenda Setting En El Nuevo Entorno Mediático

The agenda setting hypothesis in the new media environment Las hipótesis de la agenda setting en el nuevo entorno mediático NATALIA ARUGUETE1 The aim of this paper is to review El objetivo de este trabajo es the literature that discusses the basic realizar una revisión de la literatura premises of theoretical and empirical que discute premisas básicas de studies on Agenda Setting theory, los estudios teóricos y empíricos and to propose a “new frontier” in realizados desde la teoría de la the relationship between traditional Agenda Setting y propone una elite media and new media. The “nueva frontera” en la relación objective is to explore the extent entre los medios tradicionales to which the dynamics of the flow de elite y los nuevos medios. Se of information created in new procura explorar en qué medida media –particularly in blogs and la dinámica de circulación de Twitter– is distorting the boundaries información generada en los nuevos of the traditional postulates of this medios –fundamentalmente en los theoretical perspective. blogs y Twitter– está sesgando los límites existentes en los postulados tradicionales de esta perspectiva teórica. KEY WORDS: Agenda setting, new PALABRAS CLAVE: Agenda setting, media, Twitter, weblog, media nuevos medios, Twitter, weblog, agenda. agenda mediática 1 CONICET y Universidad Nacional de Quilmes, Argentina. Correo electrónico: [email protected] Castro Barros 981, PB 2, C1217 ABI; Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina. ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1571-9224 Fecha de recepción: 17/08/2015. Aceptación: 20/07/2016. Núm. 28, enero-abril, 2017, pp. 35-58. ISSN 0188-252x 35 36 Natalia Aruguete INTRODUCTION The media ecosystem has experienced a 180-degree turn. -

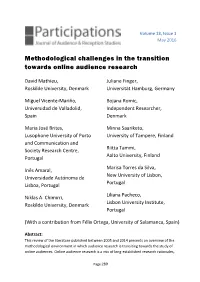

Methodological Challenges in the Transition Towards Online Audience Research

. Volume 13, Issue 1 May 2016 Methodological challenges in the transition towards online audience research David Mathieu, Juliane Finger, Roskilde University, Denmark Universität Hamburg, Germany Miguel Vicente-Mariño, Bojana Romic, Universidad de Valladolid, Independent Researcher, Spain Denmark Maria José Brites, Minna Saariketo, Lusophone University of Porto University of Tampere, Finland and Communication and Riitta Tammi, Society Research Centre, Aalto University, Finland Portugal Marisa Torres da Silva, Inês Amaral, New University of Lisbon, Universidade Autónoma de Portugal Lisboa, Portugal Liliana Pacheco, Niklas A. Chimirri, Lisbon University Institute, Roskilde University, Denmark Portugal (With a contribution from Félix Ortega, University of Salamanca, Spain) Abstract: This review of the literature published between 2005 and 2014 presents an overview of the methodological environment in which audience research is transiting towards the study of online audiences. Online audience research is a mix of long-established research rationales, Page 289 Volume 13, Issue 1 May 2016 methodical adaptations, new venues and convergent thinking. We discuss four interconnected, and sometimes contradictory, methodological trends that characterize this current environment: 1) the expansion of online ethnography and the continued importance of contextualization, 2) the influence of big data and an emphasis on uses, 3) the reliance on mixed methods and the convergence of different rationales of research, and 4) the ambiguous nature of online data and the ethical considerations for the conduct of research. In spite of a massive research activity, there remain gaps and underprivileged areas that call for a re-prioritization of research. In the conclusion of this paper, we offer recommendations to orient future research. Keywords: Online Audience, New Media, Research Method, Methodology, Literature Review, Big Data, Ethnography, Contextualization, Ethics, Mixed Method, Convergence. -

Two Concepts from Television Audience Research in Times Of

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Communication Department Faculty Publication Communication Series 2019 Two concepts from television audience research in times of datafication and disinformation: Looking back to look forward Jonathan Corpus Ong University of Massachusetts Amherst Ranjana Das University of Surrey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/communication_faculty_pubs Recommended Citation Ong, Jonathan Corpus and Das, Ranjana, "Two concepts from television audience research in times of datafication and disinformation: Looking back to look forward" (2019). Routledge Companion to Global Television. 75. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/communication_faculty_pubs/75 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Department Faculty Publication Series by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Two concepts from television audience research in times of datafication and disinformation: Looking back to look forward Jonathan Corpus Ong and Ranjana Das ABSTRACT Written by two communication scholars who came of age learning about the achievements of television audience studies and began their working lives at the birth of social media, this chapter offers reflection on their intellectual inheritance and heritage. Now engaged with various research addressing the social and -

Reconciliation of Mainstream and Critical Approaches of Media Effects Studies?

International Journal of Communication 2 (2008), 354-378 1932-8036/20080354 Mainstream Critique, Critical Mainstream and the New Media: Reconciliation of Mainstream and Critical Approaches of Media Effects Studies? MAGDALENA E. WOJCIESZAK Annenberg School for Communication University of Pennsylvania Are mainstream and critical research reconcilable? First, this paper juxtaposes two tendencies within the two approaches: homogenization and agenda setting. Doing this suggests that despite the bridges between these tendencies such as their conceptualization as powerful and longitudinal effects, there are also crucial differences to factor such as methodology, questions motivating the scholarship and interpretative framework. Secondly, this paper asks whether homogenization and agenda setting specifically, and powerful media effects generally, are still applicable in the new media environment. Although the Internet increases content amount and diversity, and might thwart the power of the media to homogenize the audience and dictate political issue salience, external factors uphold homogenization and agenda setting. This paper concludes by showing that media effects might be yet more powerful in the new media environment. Introduction Since the public reliance on the media presupposes some media impact, the question asked by communication researchers has not been “do media have an effect,” but rather “how large is the effect?” Studies designed to capture it have generally fallen within the taxonomy provided by Lazarsfeld (1948). Although Lazarsfeld (1948) advanced 16 categories of media effects, and although some scholars focus on long-term institutional changes caused by an economic structure (e.g., Bagdikian, 1985; McChesney, 2004) or technological characteristics of the media (e.g., Eisenstein, 1980; McLuhan, 1964), effects research primarily analyzes short-term media impact (see Katz, 2001 for alternative categorizations). -

The Audience Commodity in a Digital Age My Chapter

267 •T H E A U D I E N C E C O M M O D I T Y I N A D I G I T A L A GE • C H A P T E R F O U R T E E N Dallas Smythe Reloaded: Critical Media and Communication Studies Today Christian Fuchs University of Westminster he new capitalist crisis has resulted in a new interest in the works of Karl Marx. We take this as opportunity for discussing foundations of TM arxist Media and Communication Studies and which role Dallas Smythe’s works can play in this context. First, I discuss the relevance of Marx and Marxism today. Second, I give a short overview of the relevance of some elements of Dallas Smythe’s work for Marxist Media and Communication Studies. Dallas Smythe reminds us of the importance of engagement with Marx’s works for studying the media in capitalism critically. Third, I engage with the relationship of Critical Political Economy and Critical Theory in Media and Communication Studies. Both Critical Theory and Critical Political Economy of the Media and Communication have been criticized for being one-sided. Such interpretations are mainly based on selective readings. They ignore that in both approaches there has been with different weightings a focus on aspects of media commodification, audiences, ideology, and alternatives. Critical Theory and Critical Political Economy are complementary and should be combined in Critical Media and Communication studies today. Finally, I draw some conclusions. Introduction • “Marx makes a comeback” (Svenska Dagbladet. Oct 17, 2008) • “Crunch resurrects Marx” (The Independent. -

The Changing Nature of Audiences

LSE Research Online Book Section The changing nature of audiences : from the mass audience to the interactive media user Sonia Livingstone LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. Cite this version: Livingstone, S. (2003). The changing nature of audiences : from the mass audience to the interactive media user [online]. London: LSE Research Online. Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/archive/00000417 First published as: Valdivia, A. (Ed.), Companion to media studies. Oxford, UK : Blackwell Publishing, 2003, pp. 337-359 © 2003 Blackwell Publishing http://www.blackwellpublishing.com/ http://eprints.lse.ac.uk Contact LSE Research Online at: [email protected] The Changing Nature of Audiences: From the mass audience to the interactive media user Chapter to appear in Angharad Valdivia (Ed), Blackwell Companion to Media Studies Sonia Livingstone1 media@lse London School of Economics and Political Science http://www.lse.ac.uk/depts/media/people/slivingstone/index.html Changing media, changing audiences Modern media and communication technologies possess a hitherto unprecedented power to encode and circulate symbolic representations. -

What's in a “Like”? Influence of News Audience Engagement

ABSTRACT Title of Document: WHAT’S IN A “LIKE”? INFLUENCE OF NEWS AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT ON THE DELIBERATION OF PUBLIC OPINION IN THE DIGITAL PUBLIC SPHERE. Soo-Kwang Oh Doctor of Philosophy, 2014 Directed By: Linda Steiner, Ph.D. Professor Philip Merrill College of Journalism This dissertation is a mixed methods study of the influence of the “like” feature on how people discuss and understand online news. Habermas’s notion of the public sphere was that an inclusive, all-accessible and non-discriminating forum enables participants to deliberate on topics of concern. With increased interactivity and connectivity introduced by new media, commenting features have been heralded as a means to expand and accommodate discussions from audiences. In particular, by allowing people to provide feedback to each other’s ideas via “up-voting” and indicating popular “top” comments, the “like” button shows promise to be a quick and convenient way to increase participation and represent public opinion. This dissertation, however, questions whether this is true. It raises concerns about the new media landscape, asking whether the resulting digital culture helps in the proper functioning of the public sphere. To address these questions, this dissertation adopts a mixed methods approach consisting of the following: 1) Framing analysis of “top” comments and sub-comments that were posted in response to articles about recent presidential elections, examining how audiences’ framing of issues influences discussions and what strategies were used to increase “likable” -

Television, Audiences and Cultural Studies

Television, Audiences and Cultural Studies Television, Audiences and Cultural Studies presents a multifaceted exploration of audience research, in which David Morley draws on a rich body of empirical work to examine the emergence, development and future of television audience research. In addition to providing an introductory overview of the development of audience research from a cultural studies perspective, David Morley questions how class and cultural differences can affect how we interpret television, the significance of gender in the dynamics of domestic media consumption, how the media construct the ‘national family’, and how small-scale ethnographic studies can help us to understand the global-local dynamics of postmodern media systems. Morley’s work reconceptualizes the study of ideology within the broader context of domestic communications, illuminating the role of the media in articulating public and private spheres of experience and in the social organization of space, time and community. The collection contributes both to current methodological debates—for instance, the possible uses of ethnographic methods in media/cultural studies— and to new debates surrounding substantive issues. such as the functions of new (and old) media in the construction of cultural identities within a postmodern geography of the media. David Morley is Reader in Media Studies at Goldsmith’s College, University of London. He is the author of The ‘Nationwide’ Audience (1980) and Family Television (1986). 7 Television, Audiences and Cultural Studies David Morley LONDON AND NEW YORK First published 1992 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

Critical Perspectives Within Audience Research

mediaculture/03/p 12/13/01 4:09 PM Page 75 1 2 3 Chapter 4 5 3 6 7 8 9 Critical Perspectives within 0 11 Audience Research 12 13 Problems in Interpretation, Agency, 14 Structure and Ideology 15 16 17 18 19 20 The Emergence of Critical Audience Studies 21 22 asically two kinds of audience research are currently being undertaken. The 23 first and most widely circulated form of knowledge about the audience is 24 Bgathered by large-scale communication institutions. This form of investi- 25 gation is made necessary as television, radio, cinema and print production need to 26 attract viewers, listeners and readers. In order to capture an audience modern 27 institutions require knowledge about the ‘public’s’ habits, tastes and dispositions. 28 This enables media corporations to target certain audience segments with a 29 programme or textual strategy. The desire to know who is in the audience at any 30 one time provides useful knowledge that attracts advertisers, and gives broadcasters 31 certain impressions of who they are addressing. 32 Some critics have suggested that the new cable technology will be able to 33 calculate how many people in a particular area of the city watched last night’s 34 Hollywood blockbuster. This increasingly individualised knowledge base dispenses 35 with the problem of existing networks of communication where the majority of 36 advertisements might be watched by an underclass too poor to purchase the goods 37 on offer. Yet the belief that new technology will deliver a streamlined consumer- 38 hungry audience to advertisers sounds like an advanced form of capitalist wish 39 fulfilment. -

Part 1: Preliminaries

Mcquail_mass comm_7e_aw.indd 7 11/02/2020 12:10 00_MCQUAIL_7E_FM.indd 1 19/03/2020 10:19:18 AM CONTENTS Preface vii How to Use this Book xi PART 1 PRELIMINARIES 1 1 Introduction to the Book 3 2 The Rise, Decline and Return of Mass Media 29 PART 2 THEORIES 65 3 Concepts and Models for Mass Communication 67 4 Theories of Media and Society 103 5 Media, Mass Communication and Culture 143 6 New Media Theory 169 PART 3 STRUCTURES 199 7 Media Structure and Performance: Principles and Accountability 201 8 Media Economics and Governance 233 9 Global Mass Communication 269 PART 4 ORGANIZATIONS 301 10 The Media Organization: Structures and Influences 303 11 The Production of Media Culture 337 PART 5 CONTENT 369 12 Media Content: Issues, Concepts and Methods of Analysis 371 13 Media Genres, Formats and Texts 403 PART 6 AUDIENCES 431 14 Audience Theory and Research Traditions 433 15 Audience Formation and Experience 463 00_MCQUAIL_7E_FM.indd 5 19/03/2020 3:05:26 PM PART 7 EFFECTS 501 16 Processes and Models of Media Effects 503 17 A Canon of Media Effects 531 PART 8 EPILOGUE 571 18 The Future 573 Glossary 587 References 615 Author Index 657 Subject Index 663 vi CONTENTS 00_MCQUAIL_7E_FM.indd 6 19/03/2020 10:19:18 AM HOW TO USE THIS BOOK The text serves two purposes and can therefore be best used on two levels. First, it is a narrative – a ‘grand narrative’ even – of the field of media and mass communication theory and research: where it comes from, what traditions of thinking and studying have shaped it, how we come to observe and interpret media and the mass communication process today. -

Taking Audience Research Into the Age of New Media: Old Problems

Taking Audience Research into the Age of New Media: Old problems and new challenges 1 Introduction It is sometimes thought that audience research is dead, for all sorts of reasons. In the age of multiple screens, it is difficult to pinpoint when people become audiences. And, in the wake of postmodern theorizing about the fluidity of our identities, it is difficult to know how to frame questions about the interaction of media with people which can be investigated empirically. In the midst of all this confusion, we have begun a comparative ethnographic project on young people. Foremost in our minds is a consciousness of the continuities and breaks with our previous experience as television audience researchers. So, we are thinking about methodological approaches to audience study, and in particular, what methods are appropriate for audience researchers to use in the age of the internet? In the discussion which follows, we ask first why was active audience research so significant? Concomitantly, we ask why did media theory come to see empirical, qualitative audience research as important? This sets the scene for our current dilemma: must audience research start all over again with the internet, or can ideas, methods, and findings be carried forward, so we don’t reinvent the wheel? In short, we examine the parallels between researching audiences for television and for the internet, identifying the similarities and differences in the trajectories of the two bodies of research. Of course, the people are the same – the television audience has now transmogrified into the internet audience. There’s some overlap in research communities: although not all television researchers are making this move, many others are joining in the study of internet use. -

Syllabus MCTII Spr2012

19:232 Syllabus/Page 1 of 7 19:232/160:233 media communication theory ii spring 2012 professor: Meenakshi Gigi Durham E338 Adler Journalism Building 335-3355 [email protected] class meets: 12:30 - 3 p.m. Mondays in E254 AJB office hours: 9:30 -10:30 a.m. Mondays; 1 - 3 p.m. Wednesdays The School of Journalism and Mass Communication office is located in E305 AJB. The Director of the School is Prof. David Perlmutter, who may be contacted at (319) 335-3482. course overview and goals This course offers an introduction to the most significant theoretical turning points in media and cultural studies, and to the radical politics that underlies such scholarship. The course is organized in a rough chronology that traces the origins of contemporary critical/cultural studies of the media to Marxian concepts of ideology, but follows the development of these ideas through various schools of thought, illustrating how the field has grown more complex, diverse and energetic over time. Designed for the beginning graduate student, the course will provide a broad working knowledge of the main interventions in the field and of the scholars whose work fueled new trajectories. By the end of the course, students will have a familiarity with the key concepts, movements, and approaches to media and cultural studies. The primary goal of the class is for seminar participants to reach an understanding of the development and range of critical/cultural theories of the media through the process of debate, discussion, critical analysis, and synthesis. texts There is one required text for this course: Durham, Meenakshi G.