Waitperson/Customer Interaction As an Example of Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cover Letter for a Job As a Waiter/Waitress

Cover letter for a job as a waiter/waitress I. Elements to take into account when writing this cover letter Working as a waiter or waitress can initially appear to be what is classed as an unskilled job. However, the waiting staff and especially the role of sommelier and Maitre D, can be very highly skilled and well paid career paths. When applying for a position as a waiter or waitress, there are some qualities and skills that are essential to included in your application that will set your cover letter apart and show that you are the right person for the job. As part of the “front of house” team, you will be the face of the restaurant. Therefore, people skills, a welcoming nature and excellent presentation are essential qualities. Furthermore, when working in high end and Michelin Starred establishments, the service is taken into account when attributing awards, therefore these skills become even more important to mention. Team working, time keeping and being able to stay calm under pressure are also essential qualities not to be forgotten when highlighting skills in the cover letter of your application Tina Burn Joan Poole World Service 18 Jubilee Way Gainsborough Woodthorpe G4 3IO Nottingham NG7 8AN 24/5/2015 Dear Ms Burn, I am writing to you to apply for the position of Waitress at World Service, as advertised in Cuisine Weekly, 23/5/2015. I have spent the last 4 years living in France, completing a degree in Hospitality at Lyon University. During this time I gained valuable experience working in restaurants, varying from Burger bars to Michelin Starred restaurants. -

Someone's in the Kitchen Where's Dinah? Gendered Dimensions of the Professional Culinary World"

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Education Theses and Dissertations College of Education Spring 6-14-2013 SOMEONE’S IN THE KITCHEN, WHERE’S DINAH? GENDERED DIMENSIONS OF THE PROFESSIONAL CULINARY WORLD Stephanie Konkol DePaul University Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/soe_etd Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Konkol, Stephanie, "SOMEONE’S IN THE KITCHEN, WHERE’S DINAH? GENDERED DIMENSIONS OF THE PROFESSIONAL CULINARY WORLD" (2013). College of Education Theses and Dissertations. 68. https://via.library.depaul.edu/soe_etd/68 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Education at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Education Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DePaul University College of Education SOMEONE’S IN THE KITCHEN, WHERE’S DINAH? GENDERED DIMENSIONS OF THE PROFESSIONAL CULINARY WORLD A Dissertation in Education With a Concentration in Curriculum Studies by Stephanie M. Konkol Copyright 2013 Stephanie M. Konkol Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Education June 14, 2013 iii ABSTRACT Traditionally cooking is considered to be women’s work, yet the vast majority of professional chefs, particularly in the upper echelons of restaurant work, are men. These curious gendered patterns stimulated interest in delving more deeply into the gendered nature of restaurant work. Existing research on this topic has concentrated on the front of the house (dining room) but has not addressed the gendered nature of the male-dominated back of the house (kitchen). -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the SOUTHERN DISTRICT of NEW YORK GRACIELA ROMAN, on Behalf of Herself and All Others Si

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK GRACIELA ROMAN, on behalf of herself and all others similarly situated, Plaintiff, Civil Action No.: 12 CIV6156 (AKH) -against- COURT-AUTHORIZED NOTICE THE DINEX GROUP, LLC and DANIEL BOULUD, Defendants. If you have been employed as a captain, assistant captain, sommelier, server, busser, runner, bartender, barista, host, and/or other tipped employee at BAR BOULUD, DANIEL, BOULUD SUD, and/or DBGB KITCHEN AND BAR between November 1, 2009 and the present, please read this notice. Graciela Roman (“Plaintiff”) is a former Dinex employee who worked as a busser at Bar Boulud. Ms. Roman, on behalf of herself and all others similarly situated, filed a lawsuit on August 10, 2012. The lawsuit claims that The Dinex Group, LLC and Daniel Boulud (collectively, “Defendants”) failed to pay captains, assistant captains, sommeliers, servers, bussers, runners, bartenders, baristas, and hosts, the proper minimum wage and overtime pay, as well as other wages required by law. The lawsuit seeks to recover money owed in back wages and additional damages known as “liquidated damages,” along with interest, attorneys’ fees, and costs. Dinex and Mr. Boulud deny any violation of the Fair Labor Standards Act or any other law. Dinex maintains that its tip pools have always been lawful, and that tipped employees were properly paid the tip credit minimum wage. Dinex maintains that it paid tipped employees appropriately for all hours they worked. The Court has authorized the parties to send out this notice of the lawsuit. The Court has not decided who is right and who is wrong. -

Download Full Book

Vegas at Odds Kraft, James P. Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Kraft, James P. Vegas at Odds: Labor Conflict in a Leisure Economy, 1960–1985. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.3451. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/3451 [ Access provided at 25 Sep 2021 14:41 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Vegas at Odds studies in industry and society Philip B. Scranton, Series Editor Published with the assistance of the Hagley Museum and Library Vegas at Odds Labor Confl ict in a Leisure Economy, 1960– 1985 JAMES P. KRAFT The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2010 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2010 Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Mary land 21218- 4363 www .press .jhu .edu Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Kraft, James P. Vegas at odds : labor confl ict in a leisure economy, 1960– 1985 / James P. Kraft. p. cm.—(Studies in industry and society) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN- 13: 978- 0- 8018- 9357- 5 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN- 10: 0- 8018- 9357- 7 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Labor movement— Nevada—Las Vegas— History—20th century. 2. Labor— Nevada—Las Vegas— History—20th century. 3. Las Vegas (Nev.)— Economic conditions— 20th century. I. Title. HD8085.L373K73 2009 331.7'6179509793135—dc22 2009007043 A cata log record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Chef Talk: Jaryd Hearn of Polo Grill &

Chef Talk: Jaryd Hearn of Polo Grill & Bar By Abby Weingarten, Correspondent Posted Aug 2, 2017 at 10:02 AM Updated Aug 2, 2017 at 10:02 AM Interview plus recipe Jaryd Hearn returned to the Polo Grill & Bar in March to become the executive chef after working for two years at Alinea, a world- renowned, three-star Michelin restaurant in Chicago. Since coming back to Lakewood Ranch, Hearn has collaborated with chef/proprietor Tommy Klauber to bring a rustic, modern, locally-focused, seasonal approach to the menu. Q: What have been some of the highlights of your career? A: I began my restaurant career in 2008 at the age of 15. My first job was at the Grove House Grill as a busser and food runner before moving to a line cook position. During my time there, I met a chef who offered me an opportunity to work in New York. At 18, I moved to Bolton Landing. I spent a season at Lakeside Restaurant, working as a junior sous chef. This experience showed me how to handle a high- volume, fine-dining restaurant while working over 90 hours a week. After my time in New York, I returned to Bradenton to attend Keiser University for a degree in culinary arts while working at Polo Grill. In 2015, I joined the Alinea team as a chef de partie before becoming a sous chef. While with Alinea, I traveled to Dallas, Madrid, Miami and New York before relaunching Alinea -- and maintaining its three-star Michelin rating and No. 6 world ranking. -

The Role of Authenticity in the Concepts Offered by Non-Themed Domestic Restaurants in Switzerlan

sustainability Article The Importance of Being Local: The Role of Authenticity in the Concepts Offered by Non-Themed Domestic Restaurants in Switzerland Robert Home 1,* , Bernadette Oehen 1, Anneli Käsmayr 2, Joerg Wiesel 2 and Nicolaj Van der Meulen 2 1 Department of Socioeconomics, Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL), 5070 Frick, Switzerland; bernadette.oehen@fibl.org 2 Hochschule für Gestaltung und Kunst, Fachhochschule Nordwestschweiz (FHNW), Münchenstein b., 4142 Basel, Switzerland; [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (J.W.); [email protected] (N.V.d.M.) * Correspondence: robert.home@fibl.org Received: 18 March 2020; Accepted: 8 May 2020; Published: 11 May 2020 Abstract: In the highly-competitive restaurant environment, restaurateurs continually optimize the quality of their offer so that customers leave the restaurant with the intention to return and to tell others about their experience. Authenticity is among the attributes that restaurateurs seek to provide; and a wealth of study has been conducted to understand authenticity in a variety of contexts including ethnic-themed restaurants. However; insufficient attention has been given to non-themed domestic restaurants; which make up a significant proportion of available dining options. This study aimed to explore the role of authenticity as part of the concepts offered by domestic restaurants in Switzerland. Interviews with managers of 30 domestic restaurants were analyzed according to their content and interpreted according to authenticity dimensions identified by Karrebaek and Maegaard (2017) and Coupland and Coupland (2014). The approach of using a framework with four dimensions—“tradition”, “place”, “performance”, and “material”—was a useful epistemological lens to view the construct of authenticity. -

Banquet Menus

Banquet Menus Breakfast Menus CONTINENTAL BREAKFAST I Assorted Fresh Baked Pastries Seasonal Fruit Salad & Fresh Berries Assorted Cereal, Granola & Yogurt Regular & Decaffeinated Coffee, Assorted Tea Freshly Squeezed Orange & Grapefruit Juice $15.00 Per Person based on 1 hour of continuous service CONTINENTAL BREAKFAST II Assorted Fresh Baked Pastries Sliced Seasonal Fruit & Fresh Berries Assorted Cereal, Granola & Yogurt Steel Cut Oatmeal, Brown Sugar & Golden Raisins Regular & Decaffeinated Coffee, Assorted Tea Freshly Squeezed Orange & Grapefruit Juice $18.00 Per Person based on 1 hour of continuous service BOARDWALK BREAKFAST Assorted Fresh Baked Pastries Scrambled Eggs, Rosemary Breakfast Potatoes Applewood Smoked Bacon Or Homemade Pancakes, Pecan Butter, Maple Syrup Scrambled Eggs Applewood Smoked Bacon Regular & Decaffeinated Coffee, Assorted Tea Freshly Squeezed Orange & Grapefruit Juice $25.00 Per Person based on 1 hour of continuous service All Prices Subject To A 23% Service Charge And Appropriate Georgia Sales Tax Lunch Menus BOARDROOM DELI BUFFET Mixed Greens, Cucumbers, Tomatoes, White Balsamic Vinaigrette Chicken Salad & Seasonal Pasta Salad Smoked Turkey Breast, Sopresatta, Roast Beef, Honey Baked Ham Assorted Breads & Rolls, Cheese Deli Pickles, Lettuce, Tomato, Red Onion Aioli, Grainy Dijon Pesto Spread Assorted Chips Cookies & Brownies Coca Cola, Diet Coke, Sprite & Georgia Peach Iced Tea $33.00 Per Person Based on 1 hour of continuous service SANDWICH BUFFET Mixed Greens, Cucumbers, Tomatoes, White Balsamic Vinaigrette -

The Restaurant

FLASH on English for CATERING and COOKING is specifically designed for students who are studying for a career in the catering industry. It introduces the vocabulary and the language functions specific to this language sector, and includes practice exercises in all four skills. Audio files in MP3 format are available online. ISBN 978-88-536-1447-6 ISBN 978-88-536-1446-9 ISBN 978-88-536-1449-0 ISBN 978-88-536-1448-3 ISBN 978-88-536-1451-3 ISBN 978-88-536-1450-6 Contents Unit Topic Vocabulary Skills An Introduction Categories of catering Reading: about the catering industry and different types of to the Catering Venues restaurants Industry Services Speaking and listening: ordering and serving in different 1 types of catering outlets Types of catering outlets Writing: completing a catering survey and an entry for an online guide pp. 4-7 The Restaurant: Kitchen staff Reading: about roles and responsibilities of kitchen and Meet the Staff Front-of-house staff front-of-house staff Speaking and listening: exchanging information at a 2 restaurant Writing: job profiles pp. 8-11 Clothes and Clothes Reading: about kitchen staff uniforms and identifying items Personal Hygiene Hygiene of clothing; doing a kitchen hygiene quiz Speaking and listening: asking and responding to 3 information about uniforms Writing: kitchen rules; designing a personal hygiene poster pp. 12-15 In the Kitchen Kitchen areas Reading: about kitchen design and equipment Kitchen machinery and Speaking and listening: discussing kitchen organisation 4 equipment and listening for technical data Materials Writing: comparing different cooking appliances and technical data of cookware products pp. -

Signature Drinks Bar Set-Up & Bartender Package Host

BAR PACKAGES Draft Beer, Wine and Liquor Includes 2 wine glasses, 2 beer glasses and 1.5 rocks glasses per person $3/person Bottled Beer, Wine and Liquor Includes 2 wine glasses, 2 beer glasses and 1.5 rocks glasses per person $2/person Bottled Beer, Wine, Signature Drink & Liquor Includes 2 wine glasses, 2 beer glassses, 1 mixing bubble glass and 1.5 rocks glasses BAR SET-UP & BARTENDER $2.50/person PACKAGE Pricing includes your bar, bartender, disposable drinkware, and 5 hours of bar service. Additional bartenders and bars may be required. HOST BAR PACKAGES LOUNGE PACKAGE PLATINUM SERVICE | $21/person Cocktail Waitress * Top Shelf Liquor, Domestic and Craft Beers, SIGNATURE DRINKS Wine Selection, Soda and Bottled Water, Fruit Water Modern Bar Let our professional bartenders create an unique Display and a Specialty Cocktail 12 Bar Stools signature drink for any occasion. This is included in GOLD SERVICE | $16/person Lounge Furniture our Platinum Service or available to be purchased * Call Liquors, Domestic and Craft Beers, Wine Selection 8 LED Lights by the gallon. and Soda 8 Cocktail Lights Celebrate with a champagne toast. Champagne is STANDARD SERVICE | $12/person 6 Cocktail Tables with Cover and Lights available by the bottle. We offer a wide selection of * Domestic and Craft Beers, Wine Selection and Soda champagne from sweet to dry. Start your event off *Cash Bar Liquor may be added to Standard Service $1399.00 right and let the corks fly! pricing for no extra charge. Specialty alcohols are (delivered in Spfld.) Ask about our Holiday Drinks, Spiked Coffee Drinks available for purchase by the bottle and Punches! Please ask for keg pricing and details.. -

ND Career Outlook

NORTH DAKOTA CAREER CAREER RESOURCE NETWORK OUTLOOK 39TH EDITION 2021-2022 FROM THE DIRECTOR ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Career Outlook is a publication of the North Dakota Department Dear Students: of Career and Technical Education’s Career Resource Network (CRN). Career exploration and planning is an important step in planning for the future. Career Resource Network Whether you are preparing for a transition North Dakota Department of to college, researching an apprenticeship, Career and Technical Education State Capitol, 15th Floor considering military service, or entering 600 E Boulevard Ave, Dept. 270 the workforce, it is an exciting time in your Bismarck, ND 58505-0610 life. The Career Outlook magazine contains valuable information about www.cte.nd.gov the many opportunities available to you in North Dakota. Education and Telephone: 701-328-9733 training requirements, the earning potential within a career field, and the E-Mail: [email protected] number of available jobs can all be found in this issue. Use this magazine CRN Supervisor: as a resource when making informed decisions about your future. Julie Hersch CRN Administrative Assistant: As part of your plan in preparing for your future I encourage you to take Laura Glasser Career and Technical Education (CTE) courses during high school. CTE courses provide a wide range of academic and work-based learning ND STATE BOARD FOR CAREER experiences in Agriculture, Business, Family and Consumer Sciences, AND TECHNICAL EDUCATION Information Technology, Marketing, Technology Education, and Trades, Kirsten Baesler, Bismarck Industry, Technical and Health Science. These opportunities are the Jeff Fastnacht, Mandan foundation for your chosen career field. Dr. -

Catering Knowledge Organiser

AC 1.1 3. Standards and ratings The structure of the hospitality and catering industry Food hygiene standards The Food standards agency runs a scheme with local authorities where 1. Types of Provider they score businesses on a scale from zero to five to help customers make an informed choice about Residential Residential where to eat. The rating is usually non- commercial displayed as a sticker in the window commercial establishments of the premises. The scores mean: establishments Non- Non residential Hospitality at non-catering venues residential non- Contract Caterers Restaurant standards commercial commercial provide: The three main restaurant rating systems establishments establishment Range of used in the UK are Michelin stars, AA Rosette establishments food for functions such as weddings, banquets and parties in private houses. Awards and The Good Food Guide reviews: prepare and cook food and deliver it to the Michelin stars are a rating system used to venue, or cook it on site. grade restaurants for their quality: One star is a very good restaurant They may also provide staff to serve the food, if Two star is excellent cooking required. Three stars is exceptional cuisine Complete catering solutions for works canteens etc AA Rosette Awards score restaurants from one (a god restaurant that stands out from the local competition) to five (cooking that compares with the best in the world) The Good Food Guide gives restaurants a score from one (capable cooking but some inconsistencies) to ten ( perfection) 3. Standards and ratings Environmental standards 2. Suppliers Hotel and Guest house The Sustainable Restaurant standards Association awards restaurants a one-two-three Hotels and guest houses star rating in environmental Specialist are often given a star standards. -

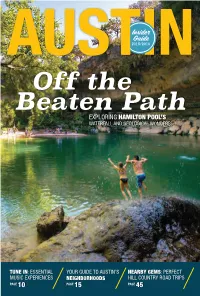

Off the Beaten Path EXPLORING HAMILTON POOL’S WATERFALL and GEOLOGICAL WONDERS

Iid Guide AUSTIN2015/2016 Off the Beaten Path EXPLORING HAMILTON POOL’S WATERFALL AND GEOLOGICAL WONDERS TUNE IN: ESSENTIAL YOUR GUIDE TO AUSTIN’S NEARBY GEMS: PERFECT MUSIC EXPERIENCES NEIGHBORHOODS HILL COUNTRY ROAD TRIPS PAGE 10 PAGE 15 PAGE 45 WE DITCHED THE LANDSCAPES FOR MORE SOUNDSCAPES. If you’re going to spend some time in Austin, shouldn’t you stay in a suite that feels like it’s actually in Austin? EXPLORE OUR REINVENTION at Radisson.com/AustinTX AUSTIN CONVENTION & VISITORS BUREAU 111 Congress Ave., Suite 700, Austin, TX 78701 800-926-2282, Fax: 512-583-7282, www.austintexas.org President & CEO Robert M. Lander Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Julie Chase Director of Marketing Communications Jennifer Walker Director of Digital Marketing Katie Cook Director of Content & Publishing Susan Richardson Director of Austin Film Commission Brian Gannon Senior Communications Manager Shilpa Bakre Tourism & PR Manager Lourdes Gomez Film, Music & Marketing Coordinator Kristen Maurel Marketing & Tourism Coordinator Rebekah Grmela AUSTIN VISITOR CENTER 602 E. Fourth St., Austin, TX 78701 866-GO-AUSTIN, 512-478-0098 Hours: Mon. – Sat. 9 a.m. – 5 p.m., Sun. 10 a.m.– 5 p.m. Director of Retail and Visitor Services Cheri Winterrowd Visitor Center Staff Erin Bevins, Harrison Eppright, Tracy Flynn, Patsy Stephenson, Spencer Streetman, Cynthia Trenckmann PUBLISHED BY MILES www.milespartnership.com Sales Office: P.O. Box 42253, Austin, TX 78704 512-432-5470, Fax: 512-857-0137 National Sales: 303-867-8236 Corporate Office: 800-303-9328 PUBLICATION TEAM Account Director Rachael Root Publication Editor Lisa Blake Art Director Kelly Ruhland Ad & Data Manager Hanna Berglund Account Executives Daja Gegen, Susan Richardson Contributing Writers Amy Gabriel, Laura Mier, Kelly Stocker SUPPORT AND LEADERSHIP Chief Executive Officer/President Roger Miles Chief Financial Officer Dianne Gates Chief Operating Officer David Burgess For advertising inquiries, please contact Daja Gegen at [email protected].