Douglas Sirk 7/6/10 3:25 PM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Melodrama, Sickness, and Paranoia: Todd Haynes and the Womanâ•Žs

University of Texas Rio Grande Valley ScholarWorks @ UTRGV Literatures and Cultural Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations College of Liberal Arts Winter 2016 Melodrama, Sickness, and Paranoia: Todd Haynes and the Woman’s Film Linda Belau The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Ed Cameron The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utrgv.edu/lcs_fac Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons Recommended Citation Belau, L., & Cameron, E. (2016). Melodrama, Sickness, and Paranoia: Todd Haynes and the Woman’s Film. Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal 46(2), 35-45. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/643290. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts at ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. It has been accepted for inclusion in Literatures and Cultural Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UTRGV. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Film & History 46.2 (Winter 2016) MELODRAMA, SICKNESS, AND PARANOIA: has so much appeal precisely for its liberation from yesterday’s film culture? TODD HAYNES AND THE WOMAN’S FILM According to Mary Ann Doane, the classical woman’s film is beset culturally by Linda Belau the problem of a woman’s desire (a subject University of Texas – Pan American famously explored by writers like Simone de Beauvoir, Julia Kristeva, Helene Cixous, and Ed Cameron Laura Mulvey). What can a woman want? University of Texas – Pan American Doane explains that filmic conventions of the period, not least the Hays Code restrictions, prevented “such an exploration,” leaving repressed material to ilmmaker Todd Haynes has claimed emerge only indirectly, in “stress points” that his films do not create cultural and “perturbations” within the film’s mise artifacts so much as appropriate and F en scène (Doane 1987, 13). -

Copyrighted Material

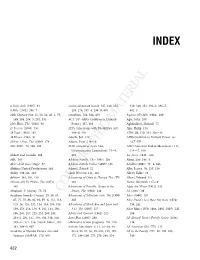

9781405170550_6_ind.qxd 16/10/2008 17:02 Page 432 INDEX 4 Little Girls (1997) 93 action-adventure movie 147, 149, 254, 339, 348, 352, 392–3, 396–7, 8 Mile (2002) 396–7 259, 276, 287–8, 298–9, 410 402–3 20th Century-Fox 21, 30, 34, 40–2, 73, actualities 106, 364, 410 Against All Odds (1984) 289 149, 184, 204–5, 281, 335 ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Agar, John 268 25th Hour, The (2002) 98 Power) 337, 410 Aghdashloo, Shohreh 75 27 Dresses (2008) 353 ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) Ahn, Philip 130 28 Days (2000) 293 398–9, 410 AIDS 99, 329, 334, 336–40 48 Hours (1982) 91 Adachi, Jeff 139 AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power see 100-to-1 Shot, The (1906) 174 Adams, Evan 118–19 ACT-UP 300 (2007) 74, 298, 300 ADC (American-Arab Anti- AIM (American Indian Movement) 111, Discrimination Committee) 73–4, 116–17, 410 Abbott and Costello 268 410 Air Force (1943) 268 ABC 340 Addams Family, The (1991) 156 Akins, Zoe 388–9 Abie’s Irish Rose (stage) 57 Addams Family Values (1993) 156 Aladdin (1992) 73–4, 246 Abilities United Productions 384 Adiarte, Patrick 72 Alba, Jessica 76, 155, 159 ability 359–84, 410 adult Western 111, 410 Albert, Eddie 72 ableism 361, 381, 410 Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet, The (TV) Albert, Edward 375 Abominable Dr Phibes, The (1971) 284 Alexie, Sherman 117–18 365 Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Algie, the Miner (1912) 312 Abraham, F. Murray 75, 76 COPYRIGHTEDDesert, The (1994) 348 MATERIALAli (2001) 96 Academy Awards (Oscars) 29, 58, 63, Adventures of Sebastian Cole, The (1998) Alice (1990) 130 67, 72, 75, 83, 92, 93, -

Pdf El Trascendentalismo En El Cine De Douglas Sirk / Emeterio Díez

EL TRASCENDENTALISMO EN EL CINE DE DOUGLAS SIRK Emeterio DÍEZ PUERTAS Universidad Camilo José Cela [email protected] Resumen: El artículo estudia la presencia del trascendentalismo en las pelí- culas que Douglas Sirk rueda para los estudios Universal Internacional Pic- tures entre 1950 y 1959. Dicha presencia se detecta en una serie de motivos temáticos y en una carga simbólica acorde con una corriente literaria y filo- sófica basada en la intuición, el sentimiento y el espíritu. Abstract: The article studies the presence of the transcendentalist in the movies that Douglas Sirk films between 1950 and 1959 for Universal Inter- national Pictures. This presence is detected in topics and symbols. Sirk uni- tes this way to a literary and philosophical movement based on the intuition, the feeling and the spirit. Palabras clave: Douglas Sirk. Trascendentalismo. Leitmotiv. Cine. Key words: Douglas Sirk. Trascendentalist. Leitmotiv. Cinema. © UNED. Revista Signa 16 (2007), págs. 345-363 345 EMETERIO DÍEZ PUERTAS Hacia 1830 surge en la costa Este de Estados Unidos un movimiento li- terario y filosófico conocido como trascendentalismo. Se trata de una co- rriente intelectual que rechaza tanto el racionalismo de la Ilustración como el puritanismo conservador y el unitarismo cristiano. Sus ideas nacen bajo el in- flujo del romanticismo inglés y alemán, en especial, de las lecturas de Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge y Thomas Carlyle. Los principales teóricos del movimiento se agrupan en torno a la ciudad de Concord, en Massachusetts, uno de los seis estados que forman Nueva Inglaterra. Con apenas cinco mil habitantes, esta pequeña localidad se convierte en el centro de toda una escuela de pensamiento. -

Bamcinématek Presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 Days of 40 Genre-Busting Films, Aug 5—24

BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, 18 days of 40 genre-busting films, Aug 5—24 “One of the undisputed masters of modern genre cinema.” —Tom Huddleston, Time Out London Dante to appear in person at select screenings Aug 5—Aug 7 The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Jul 18, 2016/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, August 5, through Wednesday, August 24, BAMcinématek presents Joe Dante at the Movies, a sprawling collection of Dante’s essential film and television work along with offbeat favorites hand-picked by the director. Additionally, Dante will appear in person at the August 5 screening of Gremlins (1984), August 6 screening of Matinee (1990), and the August 7 free screening of rarely seen The Movie Orgy (1968). Original and unapologetically entertaining, the films of Joe Dante both celebrate and skewer American culture. Dante got his start working for Roger Corman, and an appreciation for unpretentious, low-budget ingenuity runs throughout his films. The series kicks off with the essential box-office sensation Gremlins (1984—Aug 5, 8 & 20), with Zach Galligan and Phoebe Cates. Billy (Galligan) finds out the hard way what happens when you feed a Mogwai after midnight and mini terrors take over his all-American town. Continuing the necessary viewing is the “uninhibited and uproarious monster bash,” (Michael Sragow, New Yorker) Gremlins 2: The New Batch (1990—Aug 6 & 20). Dante’s sequel to his commercial hit plays like a spoof of the original, with occasional bursts of horror and celebrity cameos. In The Howling (1981), a news anchor finds herself the target of a shape-shifting serial killer in Dante’s take on the werewolf genre. -

ATINER's Conference Paper Series HUM2014-0814

ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: HUM2014-0814 Athens Institute for Education and Research ATINER ATINER's Conference Paper Series HUM2014-0814 Iconic Bodies/Exotic Pinups: The Mystique of Rita Hayworth and Zarah Leander Galina Bakhtiarova Associate Professor Western Connecticut State University USA 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: HUM2014-0814 Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece Tel: + 30 210 3634210 Fax: + 30 210 3634209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr URL Conference Papers Series: www.atiner.gr/papers.htm Printed in Athens, Greece by the Athens Institute for Education and Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction is allowed for non-commercial purposes if the source is fully acknowledged. ISSN 2241-2891 22/1/2014 2 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: HUM2014-0814 An Introduction to ATINER's Conference Paper Series ATINER started to publish this conference papers series in 2012. It includes only the papers submitted for publication after they were presented at one of the conferences organized by our Institute every year. The papers published in the series have not been refereed and are published as they were submitted by the author. The series serves two purposes. First, we want to disseminate the information as fast as possible. Second, by doing so, the authors can receive comments useful to revise their papers before they are considered for publication in one of ATINER's books, following our standard procedures of a blind review. Dr. Gregory T. Papanikos President Athens Institute for Education and Research 3 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: HUM2014-0814 This paper should be cited as follows: Bakhtiarova, G. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

University International

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Consulte As Fichas Detalhadas Do Programa

CINEMATECA PORTUGUESA–MUSEU DO CINEMA HISTÓRIAS DO CINEMA: LAURA MULVEY / DOUGLAS SIRK 4 a 8 de abril de 2016 SESSÕES-CONFERÊNCIA | APRESENTADAS E COMENTADAS POR LAURA MULVEY AS INTERVENÇÕES DE LAURA MULVEY SÃO FEITAS EM INGLÊS ALINHAMENTO DO PROGRAMA ENTRE 4 E 8 DE ABRIL: ZU NEUEN UFERN | A SCANDAL IN PARIS | ALL THAT HEAVEN ALLOWS | THE TARNISHED ANGELS | IMITATION OF LIFE segunda-feira, 4 de abril, 18h ZU NEUEN UFERN / (“Em Direcção a Novos Rumos” ou “Para Terras Distantes”) / 1937 Realização: Detlef Sierk (Douglas Sirk) / Argumento: Detlef Sierk e Kurt Heuser, com base no romance homónimo de Lovis H. Lorenz / Fotografia: Franz Weimayr / Montagem: Milo Harbich / Décors: Fritz Maurischat / Guarda-Roupa: Arno Richter / Música e Canções: Ralph Benatzky / Interpretação: Zarah Leander (Gloria Vane), Willy Birgel (Albert Finsbury), Viktor Staal (Henry), Erich Ziegel (Dr. Hoyer), Hilde von Stolz (Fanny Hoyer), Edwin Jürgensen (governador), Carola Höhn (Maria), Jakob Tiedtke (Wells), Robert Doesay (Bobby Wells), Iwa Wanja (Violet), Ernst legal (Stout), Siegfried Schürenberg (Gilbert), Lina Lossen (directora da prisão), Lissi Arna (Nelly), Herbert Hühner (patrão do “casino”), Mady Rahl, Lina castens, Curd Jürgens. Produção: Bruno Duday para a UFA / Cópia: 35mm, preto e branco, versão original em alemão com legendagem eletrónica em português, 102 minutos / Estreia Mundial: 31 de Agosto de 1937 / Inédito comercialmente em Portugal / Primeira exibição em Portugal: No Grande Auditório da Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, a 14 de Fevereiro de 1986, integrado no Ciclo de Cinema “O Musical” organizado pela Cinemateca Portuguesa e pela Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. terça-feira, 5 de abril, 18h A SCANDAL IN PARIS / (Escândalo em Paris) / 1946 Realização: Douglas Sirk / Argumento: Ellis St. -

The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA)

Recordings at Risk Sample Proposal (Fourth Call) Applicant: The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley – UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project: Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Portions of this successful proposal have been provided for the benefit of future Recordings at Risk applicants. Members of CLIR’s independent review panel were particularly impressed by these aspects of the proposal: • The broad scholarly and public appeal of the included filmmakers; • Well-articulated statements of significance and impact; • Strong letters of support from scholars; and, • A plan to interpret rights in a way to maximize access. Please direct any questions to program staff at [email protected] Application: 0000000148 Recordings at Risk Summary ID: 0000000148 Last submitted: Jun 28 2018 05:14 PM (EDT) Application Form Completed - Jun 28 2018 Form for "Application Form" Section 1: Project Summary Applicant Institution (Legal Name) The Regents of the University of California, Berkeley Applicant Institution (Colloquial Name) UC Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Project Title (max. 50 words) Saving Film Exhibition History: Digitizing Recordings of Guest Speakers at the Pacific Film Archive, 1976 to 1986 Project Summary (max. 150 words) In conjunction with its world-renowned film exhibition program established in 1971, the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) began regularly recording guest speakers in its film theater in 1976. The first ten years of these recordings (1976-86) document what has become a hallmark of BAMPFA’s programming: in-person presentations by acclaimed directors, including luminaries of global cinema, groundbreaking independent filmmakers, documentarians, avant-garde artists, and leaders in academic and popular film criticism. -

Douglas Sirk in Nazi Germany

'.seum of (VSodern Art 50'^ Anrnvprsarv NO. 40 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART FILM PROGRAM TO SHOW FOUR RARE FILMS DIRECTED BY DOUGLAS SIRK IN NAZI GERMANY Four rare films directed by Douglas Sirk during his career in Germany in the mid-1930s will be shown by The Museum of Modern Art Department of Film, August 15-18, 1980. All films will have English subtitles. Introduced by film historian Richard Traubner, the films are: TO NEW SHORES (1937, Zu neuen Ufern) and LA HABANERA (1937), both starring Zarah Leander; FINAL CHORD (1936, Schlussakkord), with Willy Birgel and Lil Dagover; and PILLARS OF SOCIETY (1935, Stutzen der Gesellschaft), with Heinrich George. Schedule as follows: TO NEW SHORES, Friday, August 15 at 6:00 (Introduced by Mr. Traubner) Sunday, August 17 at 8:30 LA HABANERA, Friday, August 15 at 8:30 Sunday, August 17 at 6:00 FINAL CHORD, Saturday, August 16 at 6:00 Monday, August 18 at 8:30 PILLARS OF SOCIETY, Saturday, August 16 at 8:30 Monday, August 18 at 6:00 Numerous Douglas Sirk films produced in Hollywood have been shown at MoMA but his career in Germany in the 30's is largely unknown. Sirk (then Detlef Sierck) had been a successful and versatile theater director before his move to the cinema (Ufa) in 1934. He carried over into film his strong sense of drama and skill with actors. Zarah Leander, the most famous of the Sirk stars, was the Nazi cinema's answer to Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich, a beautiful Swede with a deep 11 West 53 Street, New York, NY 10019. -

Program Notes by Joshua Ritter

PROGRAM NOTES BY JOSHUA RITTER In the late 1960s, political, “Jimmy” and the title song. Many other aspects of the stage social, and artistic change production similarly diverged from the film version. was sweeping across the nation. Virtually everything Universal Pictures released the film at a time when racism was in flux, including was more institutionalized, accepted, and apparent in popular interest in movie peoples’ daily lives. The film reflected this reality. There musicals. When the film was trepidation among the creative team about taking Thoroughly Modern Millie on a project that could offend modern audiences. In fact, was released in 1967, Mayer was not willing to commit to the project unless he director George Roy Hill, could portray the Asian characters in culturally appropriate producer Ross Hunter, and ways. Mayer’s solution was to make the Chinese henchmen screenwriter Richard Morris fully-realized characters that are central to the plot and were inspired by pastiche to have them speak Chinese. He later chose to embrace musicals (e.g., The Boy actress Harriet Harris’ extreme portrayal of an Asian Friend) that were gaining stereotype when she first played Mrs. Meers. The creative popularity in London at the team realized that the opportunity to juxtapose an over- time. In the waning days the-top Asian stereotype with authentic Asian characters of the Hollywood musical, would delegitimize the offensive characterization of Asian Millie spoofed silent films Americans. This daring theatrical choice worked and helped from the 1920s and embraced the farcical slapstick style of propel the show to greater acclaim. this bygone age.