Knowledge, Innovation, Social Inclusion and Their Elusive Articulation: When Isolated Policies Are Not Enough

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nationalism in the French Revolution of 1789

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Nationalism in the French Revolution of 1789 Kiley Bickford University of Maine - Main Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation Bickford, Kiley, "Nationalism in the French Revolution of 1789" (2014). Honors College. 147. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/147 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIONALISM IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION OF 1789 by Kiley Bickford A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for a Degree with Honors (History) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: Richard Blanke, Professor of History Alexander Grab, Adelaide & Alan Bird Professor of History Angela Haas, Visiting Assistant Professor of History Raymond Pelletier, Associate Professor of French, Emeritus Chris Mares, Director of the Intensive English Institute, Honors College Copyright 2014 by Kiley Bickford All rights reserved. Abstract The French Revolution of 1789 was instrumental in the emergence and growth of modern nationalism, the idea that a state should represent, and serve the interests of, a people, or "nation," that shares a common culture and history and feels as one. But national ideas, often with their source in the otherwise cosmopolitan world of the Enlightenment, were also an important cause of the Revolution itself. The rhetoric and documents of the Revolution demonstrate the importance of national ideas. -

Download Story of Easter 0.Pdf

Easter is the most important holiday of the year for Christians. To appreciate this holiday it is necessary to really grasp the drama and significance of Jesus’death and resurrection. This story is one of the most dramatic in the whole Bible. However, the Bible is an old book and not written like a modern novel. Therefore it is easy to miss the drama and significance of this story when reading it for the first time. I have written this short version of the story to help you understand this story and the significance of this holiday for us who follow Jesus. -Len Andyshak The Easter Story Matthew 26-28, Mark 14-15, Luke 22-24, John 18-21 It is noon and something has changed. The morning has been sunny and the sky blue. But now it is noon and the sky is dark. Heavy clouds hang low in the sky blocking the sun. It is noon, but it seems as if night is coming. Everything is quiet. Birds are still and people speak in whispers. Something is very wrong. Blood is slowly oozing from the nail which has been driven through Jesus’hand. He is weak and struggling to breathe as he hangs on a wooden cross by three nails which have been driven through his hands and feet. In the dim light he can hear his own heart beating, but he knows that he will die on this cross - under these dark and eerie clouds. For three years Jesus had been one of the most well known people in Israel. -

The Cover Brothers

The cover brothers Set List 60’s & older I Love Rock ‘N Roll I Believe in a thing Called Love I Am The One And Only I Gotta Feeling Brown Eyed Girl Kiss Lady Build Me Up Buttercup Like A Virgin Last Night Drive My Car Livin' On A Prayer Mr Brightside Good Vibrations Never Too Much Music Sounds Better With You Heard It On The Grapevine Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Now OMG Hound Dog Power Of Love Please Don't Stop The Music I'm A Believer Simply The Best Rock Ya Body Jail House Rock Summer Of 69 SeX On Fire Mustang Sally Sweet Child Of Mine Take Me Out - Franz Ferdinand Stand By Me Tainted Love Take Your Mama Suspicious Minds The Way You Make Me Feel Teenage Dirtbag Twist & Shout Wake Me Up Before You Go Go The Best Of You Wonderful World You Spin Me Round Use Somebody Valerie 70’s 90’s You Got The Love Alright Now Common People 2010 onwards Best Of My Love Dancing In The Moonlight Crazy Little Thing Called Love Disco 2000 Beautiful People Don’t Stop Me Now Faith Blurred Line Fly Away Don't Stop 'Til You Get Enough Counting Stars Easy Kiss From A Rose Don’t You Worry Child Hot Stuff Love Foolosophy Isn’t She Lovely Oasis Get Lucky Lovely Day Place Your Hands Happy Play That Funky Music Sing It Back Just the Way You Are Song 2 Signed Sealed Delivered Locked Out of Heaven Staying Alive What’s Up Mirrors Stuck In The Middle Superstition 2000’s Moves Like Jagger Sweet Home Alabama Set Fire to The Rain That’s The Way I Like It Beggin’ She Said We Are The Champion Black and Gold Teenage Dream Can't Get You Out OF My Head Thinkin’ Bout you Come on Girl 80’s Crazy Too Close Gotta Get Through This Wake Me Up Billie Jean Hey Ya We Found Love Dont Stop Believing Wild Ones WWW.ELM.AGENCY [email protected] 020 8123 3917 . -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1970S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1970s Page 130 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1970 25 Or 6 To 4 Everything Is Beautiful Lady D’Arbanville Chicago Ray Stevens Cat Stevens Abraham, Martin And John Farewell Is A Lonely Sound Leavin’ On A Jet Plane Marvin Gaye Jimmy Ruffin Peter Paul & Mary Ain’t No Mountain Gimme Dat Ding Let It Be High Enough The Pipkins The Beatles Diana Ross Give Me Just A Let’s Work Together All I Have To Do Is Dream Little More Time Canned Heat Bobbie Gentry Chairmen Of The Board Lola & Glen Campbell Goodbye Sam Hello The Kinks All Kinds Of Everything Samantha Love Grows (Where Dana Cliff Richard My Rosemary Grows) All Right Now Groovin’ With Mr Bloe Edison Lighthouse Free Mr Bloe Love Is Life Back Home Honey Come Back Hot Chocolate England World Cup Squad Glen Campbell Love Like A Man Ball Of Confusion House Of The Rising Sun Ten Years After (That’s What The Frijid Pink Love Of The World Is Today) I Don’t Believe In If Anymore Common People The Temptations Roger Whittaker Nicky Thomas Band Of Gold I Hear You Knocking Make It With You Freda Payne Dave Edmunds Bread Big Yellow Taxi I Want You Back Mama Told Me Joni Mitchell The Jackson Five (Not To Come) Black Night Three Dog Night I’ll Say Forever My Love Deep Purple Jimmy Ruffin Me And My Life Bridge Over Troubled Water The Tremeloes In The Summertime Simon & Garfunkel Mungo Jerry Melting Pot Can’t Help Falling In Love Blue Mink Indian Reservation Andy Williams Don Fardon Montego Bay Close To You Bobby Bloom Instant Karma The Carpenters John Lennon & Yoko Ono With My -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Glasgow School of Art: RADAR 'I Spy': Mike Leigh in the Age of Britpop (A Critical Memoir) David Sweeney During the Britpop era of the 1990s, the name of Mike Leigh was invoked regularly both by musicians and the journalists who wrote about them. To compare a band or a record to Mike Leigh was to use a form of cultural shorthand that established a shared aesthetic between musician and filmmaker. Often this aesthetic similarity went undiscussed beyond a vague acknowledgement that both parties were interested in 'real life' rather than the escapist fantasies usually associated with popular entertainment. This focus on 'real life' involved exposing the ugly truth of British existence concealed behind drawing room curtains and beneath prim good manners, its 'secrets and lies' as Leigh would later title one of his films. I know this because I was there. Here's how I remember it all: Jarvis Cocker and Abigail's Party To achieve this exposure, both Leigh and the Britpop bands he influenced used a form of 'real world' observation that some critics found intrusive to the extent of voyeurism, particularly when their gaze was directed, as it so often was, at the working class. Jarvis Cocker, lead singer and lyricist of the band Pulp -exemplars, along with Suede and Blur, of Leigh-esque Britpop - described the band's biggest hit, and one of the definitive Britpop songs, 'Common People', as dealing with "a certain voyeurism on the part of the middle classes, a certain romanticism of working class culture and a desire to slum it a bit". -

The Uses and Misuses of Popular Music Lyrics in Legal Writing, 64 Wash

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 64 | Issue 2 Article 4 Spring 3-1-2007 [Insert Song Lyrics Here]: The sesU and Misuses of Popular Music Lyrics in Legal Writing Alex B. Long Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Legal Writing and Research Commons Recommended Citation Alex B. Long, [Insert Song Lyrics Here]: The Uses and Misuses of Popular Music Lyrics in Legal Writing, 64 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 531 (2007), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol64/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [Insert Song Lyrics Here]: The Uses and Misuses of Popular Music Lyrics in Legal Writing Alex B. Long* Table of Contents I. For Those About To Rock (I Salute You) .................................... 532 II. I'm Looking Through You ........................................................... 537 A. I Count the Songs That Make the Legal Profession Sing, I Count the Songs in Most Everything, I Count the Songs That Make the Young Lawyers Cry, I Count the Songs, I Count the Songs ................................................. 537 B . A dd It U p ............................................................................... 539 C. I'm Looking Through You .................................................... 541 1. It Takes a Profession of Thousands To Hold Us Back .... 541 2. Baby Boomers Selling You Rumors of Their History ..... 544 3. -

Our Common Purpose: Reinventing American Democracy for the 21St Century (Cambridge, Mass.: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2020)

OUR COMMON REINVENTING AMERICAN PURPOSEDEMOCRACY FOR THE 21ST CENTURY COMMISSION ON THE PRACTICE OF DEMOCRATIC CITIZENSHIP Thus I consent, Sir, to this Constitution because I expect no better, and because I am not sure that it is not the best. The opinions I have had of its errors, I sacrifice to the public good. I have never whispered a syllable of them abroad. Within these walls they were born, and here they shall die. If every one of us in returning to our Constituents were to report the objections he has had to it, and endeavor to gain partizans in support of them, we might prevent its being generally received, and thereby lose all the salutary effects and great advantages resulting naturally in our favor among foreign Nations as well as among ourselves, from our real or apparent unanimity. —BENJAMIN FRANKLIN FINAL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE COMMISSION ON THE PRACTICE OF DEMOCRATIC CITIZENSHIP OUR COMMON REINVENTING AMERICAN PURPOSEDEMOCRACY FOR THE 21ST CENTURY american academy of arts & sciences Cambridge, Massachusetts © 2020 by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences All rights reserved. ISBN: 0-87724-133-3 This publication is available online at www.amacad.org/ourcommonpurpose. Suggested citation: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Our Common Purpose: Reinventing American Democracy for the 21st Century (Cambridge, Mass.: American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2020). PHOTO CREDITS iStock.com/ad_krikorian: cover; iStock.com/carterdayne: page 1; Martha Stewart Photography: pages 13, 19, 21, 24, 28, 34, 36, 42, 45, 52, -

Retrospective Analysis of Plagiaristic Practices Within a Cinematic Industry in India – a Tip in the Ocean of Icebergs

Retrospective analysis of plagiaristic practices within a cinematic industry in india – a tip in the ocean of icebergs Item Type Article Authors Sivasubramaniam, Shiva D; Paneerselvam, Umamaheswaran; Ramachandran, Sharavan Citation Umamaheswaran, P., Ramachandran, S. and Sivasubramaniam, S.D., (2020). 'Retrospective Analysis of Plagiaristic Practices within a Cinematic Industry in India–a Tip in the Ocean of Icebergs'. Journal of Academic Ethics, pp.1-11. DOI: 10.1007/ s10805-020-09360-7 DOI 10.1007/s10805-020-09360-7 Publisher Springer Journal Journal of Academic Ethics Download date 27/09/2021 02:43:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10545/624527 Journal of Academic Ethics https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-020-09360-7 Retrospective Analysis of Plagiaristic Practices within a Cinematic Industry in India – aTip in the Ocean of Icebergs Paneerselvam Umamaheswaran1 & Sharavan Ramachandran2 & Shivadas D. Sivasubramaniam3 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract Music plagiarism is defined as using tune, or melody that would closely imitate with another author’s music without proper attributions. It may occur either by stealing a musical idea (a melody or motif) or sampling (a portion of one sound, or tune is copied into a different song). Unlike the traditional music, the Indian cinematic music is extremely popular amongst the public. Since the expectations of the public for songs that are enjoyable are high, many music directors are seeking elsewhere to “borrow” tunes. Whilst a vast majority of Indian cinemagoers may not have noticed these plagiarised tunes, some journalists and vigilant music lovers have noticed these activities. This study has taken the initiative to investigate the extent of plagiaristic activities within one Indian cinematic music industry. -

Different Class Pulp Island; 1 995 Originally Published January 22, 2013 on Probably Just Hungry

Different Class Pulp Island; 1 995 originally published January 22, 2013 on Probably Just Hungry Despite a love for fish and chips and a nostalgic fondness for my punk and goth phases, I don’t claim to know much more than a little about the way class systems work in the United Kingdom. What I do understand is that it’s something that pervades the culture there, maybe a bit like race does in the U.S. — a topic with a long and complex history, further complicated by the tumult of the post-Industrial age. I mean, that would make sense looking back at the way counter culture movements seemed to flourish there. Punk, as an example, is an original concoction of the grimy underbelly of New York City, but it never really took off until it hit British shores, where it went global and remains, to this day, a defining characteristic of that generation. Of course, in 1 995, when Pulp’s Different Class was released, I knew nothing of the above, much less who Pulp was. In fact, I wouldn’t even discover the band/album until almost 1 0 years later. Even then, well into high school, I wasn’t aware of any of the topical undercurrents on the album. (Well, aside from the smarmy swagger of Jarvis Cocker, which reach near-predatory levels here.) But now, much later, it clicks. With a name like Different Class, a track titled ”Common People” and lyrics like, ”Mis-shapes, mistakes, misfits / raised on a diet of broken biscuits / We don’t look the same as you / We don’t do the things you do / but we live around here too,” there’s no question that this is an album about class. -

Gender Role Construction in the Beatles' Lyrics

“SHE LOVES YOU, YEAH, YEAH, YEAH!”: GENDER ROLE CONSTRUCTION IN THE BEATLES’ LYRICS Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magister der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von Mario Kienzl am Institut für: Anglistik Begutachter: Ao.Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr.phil. Hugo Keiper Graz, April 2009 Danke Mama. Danke Papa. Danke Connie. Danke Werner. Danke Jenna. Danke Hugo. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 4 2. The Beatles: 1962 – 1970...................................................................................................... 6 3. The Beatles’ Rock and Roll Roots .................................................................................... 18 4. Love Me Do: A Roller Coaster of Adolescence and Love............................................... 26 5. Please Please Me: The Beatles Get the Girl ..................................................................... 31 6. The Beatles enter the Domestic Sphere............................................................................ 39 7. The Beatles Step Out.......................................................................................................... 52 8. Beatles on the Rocks........................................................................................................... 57 9. Do not Touch the Beatles.................................................................................................. -

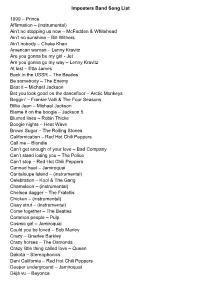

Imposters Band Song List 1999

Imposters Band Song List 1999 – Prince Affirmation – (instrumental) Ain’t no stopping us now – McFadden & Whitehead Ain’t no sunshine – Bill Withers Ain’t nobody – Chaka Khan American woman – Lenny Kravitz Are you gonna be my girl - Jet Are you gonna go my way – Lenny Kravitz At last – Etta James Back in the USSR – The Beatles Be somebody – The Enemy Beat it – Michael Jackson Bet you look good on the dancefloor – Arctic Monkeys Beggin’ – Frankie Valli & The Four Seasons Billie Jean – Michael Jackson Blame it on the boogie – Jackson 5 Blurred lines – Robin Thicke Boogie nights – Heat Wave Brown Sugar – The Rolling Stones Californication – Red Hot Chili Peppers Call me – Blondie Can’t get enough of your love – Bad Company Can’t stand losing you – The Police Can’t stop – Red Hot Chili Peppers Canned heat – Jamiroquai Cantaloupe Island – (instrumental) Celebration – Kool & The Gang Chameleon – (instrumental) Chelsea dagger – The Fratellis Chicken – (instrumental) Cissy strut – (instrumental) Come together – The Beatles Common people – Pulp Cosmic girl – Jamiroquai Could you be loved – Bob Marley Crazy – Gnarles Barkley Crazy horses – The Osmonds Crazy little thing called love – Queen Dakota – Stereophonics Dani California – Red Hot Chili Peppers Deeper underground – Jamiroquai Déjà vu – Beyonce Diggin’ on James Brown – Tower of Power Dirty Diana – Michael Jackson Disco 2000 – Pulp Disco inferno – The Trammps Don’t look back into the sun – The Libertines Don’t stop ‘til you get enough – Michael Jackson Don’t tell me – Madonna Don’t you worry