Is the Helmeted Honeyeater Doomed? by ROY P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Age and Sex Characteristics of the Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus Melanops Cassidix in the Hand

Corella, 2000, 24(3): 30-35 AGE AND SEX CHARACTERISTICS OF THE HELMETED HONEVEATER Lichenostomus melanops cassidix IN THE HAND 1 2 1 4 DONALD C. FRANKLIN • , IAN J. SMALES3, BRUCE R. QUIN and PETER W. MENKHORST 1 Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Yellingbo Nature Conservation Reserve, Macclesfield Road, Yellingbo, Victoria 3139 2 Current address: P.O. Box 987, Nightcliff, Northern Territory 0814. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Zoological Parks and Gardens Board of Victoria, P.O. Box 248, Healesville, Victoria 3777 • Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Parks, Flora and Fauna Program, P.O. Box 500, East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Received: 3 February, 2000 There has been a range of opinions about sexual dimorphism in the Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix despite little supporting data, yet these opinions have played an historic role in the definition of the taxon. We demonstrate that males are, on average, larger than females in a range of characters, but there is no absolute morphological distinction. We were unable to identify any consistent or marked differences in plumage between the sexes. There are also few differences between the plumage of young birds and adults, the only categoric difference being in the shape of the tip of the rectrices. However, juveniles have a yellow gape, bill and palate whereas those of adults are black. Gape colour is the more persistent of the three juvenile traits, but its persistence varies greatly between individuals. There are also differences between juveniles and adults in the colour of the legs and eyes. In its age and sex characteristics, the Helmeted Honeyeater closely resembles the inland race of the Yellow-tufted Honeyeater L. -

Referral of Proposed Action

Referral of proposed action What is a referral? The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (the EPBC Act) provides for the protection of the environment, especially matters of national environmental significance (NES). Under the EPBC Act, a person must not take an action that has, will have, or is likely to have a significant impact on any of the matters of NES without approval from the Commonwealth Environment Minister or the Minister’s delegate. (Further references to ‘the Minister’ in this form include references to the Commonwealth Environment Minister or the Minister’s delegate.) To obtain approval from the Minister, a proposed action must be referred. The purpose of a referral is to enable the Minister to decide whether your proposed action will need assessment and approval under the EPBC Act. Your referral will be the principal basis for the Minister’s decision as to whether approval is necessary and, if so, the type of assessment that will be undertaken. These decisions are made within 20 business days, provided sufficient information is provided in the referral. Who can make a referral? Referrals may be made by or on behalf of a person proposing to take an action, the Commonwealth or a Commonwealth agency, a state or territory government, or agency, provided that the relevant government or agency has administrative responsibilities relating to the action. When do I need to make a referral? A referral must be made by the person proposing to take an action if the person thinks that the action for actions -

The Foraging Ecology and Habitat Selection of the Yellow-Plumed Honeyeater (Lichenostomus Ornatus) at Dryandra Woodland, Western Australia

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 1997 The foraging ecology and habitat selection of the Yellow-Plumed Honeyeater (Lichenostomus Ornatus) at Dryandra Woodland, Western Australia Kellie Wilson Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, K. (1997). The foraging ecology and habitat selection of the Yellow-Plumed Honeyeater (Lichenostomus Ornatus) at Dryandra Woodland, Western Australia. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/ 293 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/293 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

CITES Helmeted Honeyeater Review

Original language: English AC28 Doc. 20.3.3 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ___________________ Twenty-eighth meeting of the Animals Committee Tel Aviv (Israel), 30 August-3 September 2015 Interpretation and implementation of the Convention Species trade and conservation Periodic review of species included in Appendices I and II [Resolution Conf 14.8 (Rev CoP16)] PERIODIC REVIEW OF LICHENOSTOMUS MELANOPS CASSIDIX 1. This document has been submitted by Australia.* 2. After the 25th meeting of the Animals Committee (Geneva, July 2011) and in response to Notification No. 2011/038, Australia committed to the evaluation of Lichenostomus melanops cassidix as part of the Periodic review of the species included in the CITES Appendices. 3. This taxon is endemic to Australia. 4. Following our review of the status of this species, Australia recommends that L. m. cassidix be transferred from Appendix I to Appendix II in accordance with Resolution 9.24 (Rev Cop16) Annex 4 A.1 and A.2(a)(i). * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. AC28 Doc. 20.3.3 – p. 1 AC28 Doc. 20.3.3 Annex CoP17 Prop. xx CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ DRAFT PROPOSAL TO AMEND THE APPENDICES (in accordance with Annex 4 to Resolution Conf. -

LINKING LANDSCAPE DATA with POPULATION VIABILITY ANALYSIS: MANAGEMENT OPTIONS for the HELMETED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus Melanops Cassidix

This is a preprint of an article published in Biological Conservation Volume 73 (1995) pages 169-176. © 1995 Elsevier Science Limited. All rights reserved. LINKING LANDSCAPE DATA WITH POPULATION VIABILITY ANALYSIS: MANAGEMENT OPTIONS FOR THE HELMETED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops cassidix H. Resit Akçakaya Applied Biomathematics, 100 North Country Road, Setauket, New York 11733, USA Michael A. McCarthy and Jennie L. Pearce Forestry Section, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia ABSTRACT Habitats used by most species are becoming increasingly fragmented, requiring a metapopulation modelling approach to population viability analysis. Recognizing habitat patchiness from an endangered species' point of view requires utilization of spatial information on habitat suitability. Both of these requirements may be met by linking metapopulation modelling with landscape data using GIS technology. We present a PVA model that links spatial data directly to a metapopulation model for extinction risk assessment, viability analysis, reserve design and wildlife management. The use of the model is demonstrated by an application to the spatial dynamics of the Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix, an endangered bird species endemic to Victoria, Australia. We use spatial data, organized by a GIS, on the habitat requirements of the helmeted honeyeater to define the patch structure. We then combine this patch structure with demographic data to build a metapopulation model, and use the model to analyze the effectiveness of translocations as a conservation strategy for the helmeted honeyeater. Key words: habitat suitability model; helmeted honeyeater; metapopulation model; population viability analysis; translocation. INTRODUCTION Rare and threatened species are adversely affected by changes in the landscape that cause habitat loss and habitat fragmentation. -

National Recovery Plan for Helmeted Honeyeater (Lichenostomus

National Recovery Plan for the Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix Peter Menkhorst in conjunction with the Helmeted Honeyeater Recovery Team Compiled by Peter Menkhorst (Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria) in conjunction with the national Helmeted Honeyeater Recovery Team. Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) Melbourne, 2008. © State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2006 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. ISBN 1 74152 351 6 This is a Recovery Plan prepared under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, with the assistance of funding provided by the Australian Government. This Recovery Plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. An electronic version of this document is available on the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts website www.environment.gov.au For more information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre 136 186 Citation: Menkhorst, P. -

Helmeted Honeyeater Version Has Been Prepared for Web Publication

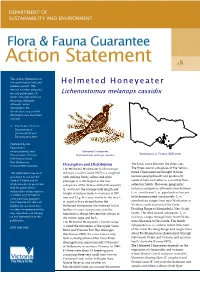

#8 This Action Statement was first published in 1992 and remains current. This Helmeted Honeyeater version has been prepared for web publication. It Lichenostomus melanops cassidix retains the original text of the action statement, although contact information, the distribution map and the illustration may have been updated. © The State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment, 2003 Published by the Department of Sustainability and Helmeted Honeyeater Environment, Victoria. (Lichenostomus melanops cassidix) Distribution in Victoria (DSE 2002) 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne, The birds move between the three sites. Victoria 3002 Australia Description and Distribution The Helmeted Honeyeater (Lichenostomus The three coastal subspecies of the Yellow- This publication may be of melanops cassidix Gould 1867) is a songbird tufted Honeyeater are thought to have assistance to you but the with striking black, yellow and olive become geographically and genetically State of Victoria and its plumage. It is the largest of the four isolated from each other as a result of their employees do not guarantee subspecies of the Yellow-tufted Honeyeater sedentary habits. However, geographic that the publication is (L. melanops): the average total length and isolation and genetic differentiation between without flaw of any kind or weight of mature males is in excess of 200 L. m. cassidix and L. m. gippslandicus has yet is wholly appropriate for to be demonstrated conclusively. L. m. your particular purposes mm and 32 g. It is very similar to the race L. gippslandicus ranges from near Warburton in and therefore disclaims all m. gippslandicus, except that in the liability for any error, loss Helmeted Honeyeater the forehead tuft of Victoria, south and east of the Great or other consequence which feathers is more conspicuous and the Dividing Range to Merrimbula, New South may arise from you relying transition is abrupt between the colours of Wales. -

Helmeted Honeyeater (Yellow-Tufted Honeyeater: West Gippsland)

RECOVERY OUTLINE Helmeted Honeyeater (Yellow-tufted Honeyeater: west Gippsland) 1 Family Meliphagidae 2 Scientific name Lichenostomus melanops cassidix (Gould, 1867) 3 Common name Helmeted Honeyeater 4 Conservation status Critically Endangered: B1+2c, D 5 Reasons for listing This species is found in a single area of about 5 km2 (Critically Endangered: B1) and the quality of habitat is still declining (B2c). The wild population also contains fewer than 50 mature individuals (D). Estimate Reliability Extent of occurrence 5 km2 high trend stable high Area of occupancy 5 km2 high trend stable high No. of breeding birds 48 high trend increasing high 9 Ecology No. of sub-populations 1 high The Helmeted Honeyeater inhabits streamside lowland Generation time 5 years medium swamp forest. It is rarely found far from water and all 6 Infraspecific taxa current birds live in closed riparian forest dominated L. m. melanops (south-eastern Australia, south or east of by Mountain Swamp Gum Eucalyptus camphora where the Great Dividing Ra.) and L. m. meltoni (south- they feed among the decorticating bark (Pearce et al., eastern Australia, inland slopes of the Great Dividing 1994). Some pairs feed on Swamp Gum E. ovata in Ra.). Both are phenotypically and genetically distinct winter and they will also use patchy thickets of Scented from the Helmeted Honeyeater (Blackney and Paperbark Melaleuca squarrosa, Woolly Tea-tree Menkhorst, 1993, Damiano, 1996). Leptospermum lanigerum, Prickly Tea-tree L. juniperinum and sedges (Backhouse, 1987, Blackney and 7 Past range and abundance Menkhorst, 1993, Moysey, 1997, Menkhorst et al., Endemic to Victoria. Scattered distribution through 1999). -

Regents Roam V18 November 20092009

WHERE THE REGENTS ROAM V18 NOVEMBER 20092009 WelcomeWelcome to thethe next eeditiondition ooff WWherehere TThehe Regents Roam, thethe newsletternewsletter forfor thethe recoveryrecovery program offh the Regent R HHoneyeater. CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT Have you ever wondered what it’s like to run a captive breeding program for an endangered species? If so, read on for a fi rst hand account of the program to breed Regent Honeyeaters at Taronga Zoo from the perspective of Michael Shiels, Supervisor of Taronga’s Bird Unit and member of the Regent Honeyeater Recovery Team: Captive breeding an management of Regent Honeyeaters is one of many steps being implemented by the recovery team to address the declines of this charismatic bird. The objectives of the captive management component are to maintain the captive population of Regent Honeyeaters at a size which will provide adequate stock to: provide insurance against the demise of the wild population; continuously improve captive-breeding and husbandry techniques; and provide adequate stock for trials of release strategies. This is all conducted while maintaining 90% of the wild heterozygosity (genetic diversity) in the captive population. During 1995 a team of community bird groups, observers and Taronga Staff, coordinated by the National Recovery Team Coordinator collaborated to collect wild Regent Honeyeater nestlings and their nests from Chiltern State Park (now Chiltern-Mt Pilot National Park) in Victoria. The age at which the nestlings were collected (4-6 days) ensured that the nestlings had a few days of being reared by their parents before being acclimatised to an artifi cial diet. This strategy was used to minimise the risk associated with collection, and to give the chicks a chance to be exposed to natural gut fl ora from their parents. -

Principal's Report

NEWSLETTER N0 38 28TH NOVEMBER 2019 LAST DAY FOR TERM 4 - FRIDAY 20TH DECEMBER AT 2.30PM FIRST DAY FOR TERM 1 - THURSDAY 30TH JANUARY 2020 CANTEEN IS OPEN MONDAY, WEDNESDAY & FRIDAY PRINCIPAL’S REPORT GRADE PLACEMENT LISTS We will be publishing class lists on Friday 6 December on the Parent Portal on Sentral at 3.00pm. We will not be placing class lists on windows and doors located around the school this year – for privacy and security reasons. Please contact our office staff if you experience any problems with accessing the Parent Portal. HETTIE & HARRY’S FOREST ADVENTURE AR CAPABLE BOOK I am really pleased to announce that our Augmented Reality (AR) capable children’s book is now in production and will be available for purchase from next week at the school. This project, which aims to better engage children in their reading and learning, is quite unique in that there are precious few AR capable children’s story books available anywhere. That we have developed the book, as a school, is something of which we can all be very proud. The book has a strong environmental focus, with Harry, as the helmeted honeyear, being our school’s emblem, and Hettie bing the forest keeper. In developing this project, we have formed a partnership with Deakin University with a view to having AR researched as a mechanism by which student engagement can be enhanced. When purchasing the book from our school, it should be noted that all proceeds from the sale of the book remain with Berwick Lodge P.S. -

Vulnerable Victorians

Vulnerable Victorians DSE’s threatened species recovery projects February 2006 Helmeted Honeyeater The Helmeted Honeyeater is Victoria’s bird emblem and sadly, is in danger of extinction. Helmeted Honeyeaters live in narrow bands of swamp or creek vegetation within the Yellingbo Nature Conservation Reserve, 50 km east of Melbourne. The removal of native vegetation and drainage of swamps have destroyed large areas of their habitat causing the decline of the species. Another threat is a native bird, the Bell Miner, which aggressively excludes Helmeted Honeyeaters from areas of habitat. The campaign to save the Helmeted Honeyeater from the threat of extinction began back in the 1960s, leading to the creation of the Yellingbo Nature Conservation Reserve, and it remains a symbol of how people can come together to recognise environmental threats and take action to prevent them. Among the groups which have joined DSE and played a huge part are the Friends of the Helmeted Honeyeater, Birds Australia, Trust for Nature and the Bird Observers Club of Australia, as well as hundreds of other volunteers. Then there are organisations like Parks Victoria and Zoos Victoria, Melbourne Water and more, sharing their knowledge and expertise. In 2005 they celebrated the 10th anniversary of the hatching of the first Helmeted Honeyeater born in the wild from captive parents. Back in 1995 a pair of Helmeted Honeyeaters were taken from Healesville Sanctuary to an aviary along Woori Yallock Creek in Yellingbo Nature Conservation Reserve. The pair built a nest in the aviary and a chick was hatched. A week later the chick's parents were released into the wild, as so many have been over the past decade, in an effort to rescue the species from extinction. -

HELMETED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus Melanops Cassidix Critically Endangered

Zoos Victoria’s priority species HELMETED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops cassidix Critically Endangered Zoos Victoria is committed to saving the The release of captive-bred birds has Helmeted Honeyeater. With a highly restricted played an important role in boosting the size distribution, this beautiful bird is at risk of of the wild Helmeted Honeyeater population. extinction due to the loss of its streamside forest We are also currently working hard with habitat. Zoos Victoria’s Healesville Sanctuary partners to increase the condition and has led the Helmeted Honeyeater captive- extent of habitat available for the honeyeater breeding program for more than 20 years. and to identify new release localities. Zoos Victoria is committed to Fighting Extinction We are focused on working with partners to secure the survival of our priority species before it is too late. Zoos Victoria has been involved in the Helmeted Honeyeater recovery program since 1989. We supplement wild populations through an annual release of captive-bred birds, and provide opportunities for visitors to connect with this iconic bird when they visit Healesville Sanctuary and Melbourne Zoo. KEY PROGRAM OBJECTIVES Helmeted Honeyeaters rely on dense shrubs • Achieve a stable population of at least for nesting and food, and are threatened by How can I help? 500 Helmeted Honeyeaters spread across vegetation dieback in sections of their habitat five localities. and a lack of natural regeneration. We are working hard to boost • Improve the condition and extent of habitat Strong foundations are in place for the future the production of captive- available for Helmeted Honeyeaters along recovery of Helmeted Honeyeater populations.