Regents Roam V18 November 20092009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Age and Sex Characteristics of the Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus Melanops Cassidix in the Hand

Corella, 2000, 24(3): 30-35 AGE AND SEX CHARACTERISTICS OF THE HELMETED HONEVEATER Lichenostomus melanops cassidix IN THE HAND 1 2 1 4 DONALD C. FRANKLIN • , IAN J. SMALES3, BRUCE R. QUIN and PETER W. MENKHORST 1 Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Yellingbo Nature Conservation Reserve, Macclesfield Road, Yellingbo, Victoria 3139 2 Current address: P.O. Box 987, Nightcliff, Northern Territory 0814. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Zoological Parks and Gardens Board of Victoria, P.O. Box 248, Healesville, Victoria 3777 • Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Parks, Flora and Fauna Program, P.O. Box 500, East Melbourne, Victoria 3002 Received: 3 February, 2000 There has been a range of opinions about sexual dimorphism in the Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix despite little supporting data, yet these opinions have played an historic role in the definition of the taxon. We demonstrate that males are, on average, larger than females in a range of characters, but there is no absolute morphological distinction. We were unable to identify any consistent or marked differences in plumage between the sexes. There are also few differences between the plumage of young birds and adults, the only categoric difference being in the shape of the tip of the rectrices. However, juveniles have a yellow gape, bill and palate whereas those of adults are black. Gape colour is the more persistent of the three juvenile traits, but its persistence varies greatly between individuals. There are also differences between juveniles and adults in the colour of the legs and eyes. In its age and sex characteristics, the Helmeted Honeyeater closely resembles the inland race of the Yellow-tufted Honeyeater L. -

Referral of Proposed Action

Referral of proposed action What is a referral? The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (the EPBC Act) provides for the protection of the environment, especially matters of national environmental significance (NES). Under the EPBC Act, a person must not take an action that has, will have, or is likely to have a significant impact on any of the matters of NES without approval from the Commonwealth Environment Minister or the Minister’s delegate. (Further references to ‘the Minister’ in this form include references to the Commonwealth Environment Minister or the Minister’s delegate.) To obtain approval from the Minister, a proposed action must be referred. The purpose of a referral is to enable the Minister to decide whether your proposed action will need assessment and approval under the EPBC Act. Your referral will be the principal basis for the Minister’s decision as to whether approval is necessary and, if so, the type of assessment that will be undertaken. These decisions are made within 20 business days, provided sufficient information is provided in the referral. Who can make a referral? Referrals may be made by or on behalf of a person proposing to take an action, the Commonwealth or a Commonwealth agency, a state or territory government, or agency, provided that the relevant government or agency has administrative responsibilities relating to the action. When do I need to make a referral? A referral must be made by the person proposing to take an action if the person thinks that the action for actions -

Yellow Wattlebird 9 Giving Swift Parrots a Helping Hand 10 Conservation Landholders Tasmania: Next Event 12 Selling Property? 12

The RunningPostman Newsletter of the Private Land Conservation Program December 2016 • Issue 22 Building partnerships with landowners for the sustainable management Print ISSN 1835-6141 and conservation of natural values across the landscape. Online ISSN 2204-390X Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment 1 Manager’s message – December 2016 What a year! As 2016 comes to an Our floodplains and river systems This is a significant milestone for end, it is timely to take a moment are dynamic and erosion and the program and demonstrates to reflect on the amazing events deposition are timeless processes. the amazing contribution that that we have seen in Tasmania Small fragments of wood we private land managers can make recently. Our wilderness areas have found embedded in the bottom to landscape scale conservation. been visited by drought, fires and of a floodplain scour have been The act of conserving important then some of the heaviest rainfall dated at 2500 years old, this debris places on private land continues to recorded high in our northern may have been deposited on that be one of the most fundamentally flowing catchments. plain all those years ago in a big practical actions that can be taken flood, or at any time since. But by individuals to protect biodiversity. These amazing natural events the simple reality that wood and remind us of the inscrutable power earth has floated down these I wish all of the contributors to the of our physical environment, and systems for thousands of years protection of nature on private land the timelessness of our landscapes. -

The Foraging Ecology and Habitat Selection of the Yellow-Plumed Honeyeater (Lichenostomus Ornatus) at Dryandra Woodland, Western Australia

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 1997 The foraging ecology and habitat selection of the Yellow-Plumed Honeyeater (Lichenostomus Ornatus) at Dryandra Woodland, Western Australia Kellie Wilson Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Ornithology Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, K. (1997). The foraging ecology and habitat selection of the Yellow-Plumed Honeyeater (Lichenostomus Ornatus) at Dryandra Woodland, Western Australia. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/ 293 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/293 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

Yellow Throat Turns 100! Editor YELLOW THROAT This Issue Is the 100Th Since Yellow Throat First Appeared in March 2002

Yellow Throat turns 100! Editor YELLOW THROAT This issue is the 100th since Yellow Throat first appeared in March 2002. To mark the occasion, and to complement the ecological focus of the following article by Mike The newsletter of BirdLife Tasmania Newman, here is a historical perspective, which admittedly goes back a lot further than a branch of BirdLife Australia the newsletter, and the Number 100, July 2018 organisation! Originally described by French ornithologist General Meeting for July Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot in 1817, and Life Sciences Building, UTas, named Ptilotus Flavillus, specimens of Thursday, 12 July, 7.30 p.m. the Yellow-throated Matthew Fielding: Raven populations are enhanced by wildlife roadkill but do not Honeyeater were impact songbird assemblages. ‘collected’ by John Future land-use and climate change could supplement populations of opportunistic Gould during his visit predatory birds, such as corvids, resulting in amplified predation pressure and negative to Tasmania with his effects on populations of other avian species. Matt, a current UTas PhD candidate, will wife Elizabeth in 1838. provide an overview of his Honours study on the response of forest raven (Corvus This beautiful image tasmanicus) populations to modified landscapes and areas of high roadkill density in south- was part of the eastern Tasmania. exhibition ‘Bird Caitlan Geale: Feral cat activity at seabird colonies on Bruny Island. Woman: Elizabeth Using image analysis and modelling, Caitlin’s recent Honours project found that feral cats Gould and the birds of used the seabird colonies studied as a major food resource during the entire study period, and Australia’ at the native predators did not appear to have a large impact. -

CITES Helmeted Honeyeater Review

Original language: English AC28 Doc. 20.3.3 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ___________________ Twenty-eighth meeting of the Animals Committee Tel Aviv (Israel), 30 August-3 September 2015 Interpretation and implementation of the Convention Species trade and conservation Periodic review of species included in Appendices I and II [Resolution Conf 14.8 (Rev CoP16)] PERIODIC REVIEW OF LICHENOSTOMUS MELANOPS CASSIDIX 1. This document has been submitted by Australia.* 2. After the 25th meeting of the Animals Committee (Geneva, July 2011) and in response to Notification No. 2011/038, Australia committed to the evaluation of Lichenostomus melanops cassidix as part of the Periodic review of the species included in the CITES Appendices. 3. This taxon is endemic to Australia. 4. Following our review of the status of this species, Australia recommends that L. m. cassidix be transferred from Appendix I to Appendix II in accordance with Resolution 9.24 (Rev Cop16) Annex 4 A.1 and A.2(a)(i). * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. AC28 Doc. 20.3.3 – p. 1 AC28 Doc. 20.3.3 Annex CoP17 Prop. xx CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ DRAFT PROPOSAL TO AMEND THE APPENDICES (in accordance with Annex 4 to Resolution Conf. -

LINKING LANDSCAPE DATA with POPULATION VIABILITY ANALYSIS: MANAGEMENT OPTIONS for the HELMETED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus Melanops Cassidix

This is a preprint of an article published in Biological Conservation Volume 73 (1995) pages 169-176. © 1995 Elsevier Science Limited. All rights reserved. LINKING LANDSCAPE DATA WITH POPULATION VIABILITY ANALYSIS: MANAGEMENT OPTIONS FOR THE HELMETED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops cassidix H. Resit Akçakaya Applied Biomathematics, 100 North Country Road, Setauket, New York 11733, USA Michael A. McCarthy and Jennie L. Pearce Forestry Section, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia ABSTRACT Habitats used by most species are becoming increasingly fragmented, requiring a metapopulation modelling approach to population viability analysis. Recognizing habitat patchiness from an endangered species' point of view requires utilization of spatial information on habitat suitability. Both of these requirements may be met by linking metapopulation modelling with landscape data using GIS technology. We present a PVA model that links spatial data directly to a metapopulation model for extinction risk assessment, viability analysis, reserve design and wildlife management. The use of the model is demonstrated by an application to the spatial dynamics of the Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix, an endangered bird species endemic to Victoria, Australia. We use spatial data, organized by a GIS, on the habitat requirements of the helmeted honeyeater to define the patch structure. We then combine this patch structure with demographic data to build a metapopulation model, and use the model to analyze the effectiveness of translocations as a conservation strategy for the helmeted honeyeater. Key words: habitat suitability model; helmeted honeyeater; metapopulation model; population viability analysis; translocation. INTRODUCTION Rare and threatened species are adversely affected by changes in the landscape that cause habitat loss and habitat fragmentation. -

National Recovery Plan for Helmeted Honeyeater (Lichenostomus

National Recovery Plan for the Helmeted Honeyeater Lichenostomus melanops cassidix Peter Menkhorst in conjunction with the Helmeted Honeyeater Recovery Team Compiled by Peter Menkhorst (Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria) in conjunction with the national Helmeted Honeyeater Recovery Team. Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) Melbourne, 2008. © State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2006 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. ISBN 1 74152 351 6 This is a Recovery Plan prepared under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, with the assistance of funding provided by the Australian Government. This Recovery Plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. An electronic version of this document is available on the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts website www.environment.gov.au For more information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre 136 186 Citation: Menkhorst, P. -

THE Tasmanian Naturalist

THE Tasmanian Naturalist Number 116 1994 llBRAVX CTORIA museum Published by Tasmanian Field Naturalists Club Inc. NUMBER 116 1994 ISSN 0819-6826 IBRMVI Naturalist T.F.N.C. EDITOR: ROBERT J. TAYLOR CONTENTS Fauna of Mount Wellington. Robert J.Taylor and Peter B. McQuillan 2 The occurrence of the metallic skink Niveoscincus mettallicus in the intertidal zone in south-west Tasmania. M. Schulz and K. Kristensen 20 A brief history of Orielton Lagoon and its birds. Len E. Wall 23 First recording of the European shore crab Carcinus maenas in Tasmania. N.C. Gardner, S.Kzva and A. Paturusi 26 Pultenaea subumbellata and Pultenaea selaginoides - not quite the plants you think. A.J.J. Lynch 29 Distribution and habitat of the moss froglet, a new undescribed species from south west Tasmania. David Ziegler 31 Identity and distribution of large Roblinella land snails in Tasmania. Kevin Bonham 38 Aspley River South Esk Pine Reserve: a survey of its vascular plants and recommendations for management. David Ziegler and Stephen Harris 45 Evaluating Tasmania's rare and threatened species. Sally L. Bryant and Stephen Harris 52 A sugar glider on Mount Wellington. Len E. Wall 58 Book Review 59 Published annually by The Tasmanian Field Naturalists Club Inc., G.P.O. Box 68A, Hobart, Tasmania 7001 The Tasmanian Naturalist (1994) 116: 2-19 FAUNA OF MOUNT WELLINGTON Robert J. Taylor1 and Peter B. McQuillan2 139 Parliament Street, Sandy Bay, Hobart, Tasmania 7005 2 Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Tasmania, G.P.O. Box 252C, Hobart, Tasmania 7001 Abstract. This paper reviews information on the fauna of Mt. -

Helmeted Honeyeater Version Has Been Prepared for Web Publication

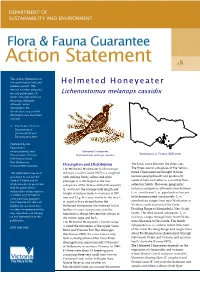

#8 This Action Statement was first published in 1992 and remains current. This Helmeted Honeyeater version has been prepared for web publication. It Lichenostomus melanops cassidix retains the original text of the action statement, although contact information, the distribution map and the illustration may have been updated. © The State of Victoria, Department of Sustainability and Environment, 2003 Published by the Department of Sustainability and Helmeted Honeyeater Environment, Victoria. (Lichenostomus melanops cassidix) Distribution in Victoria (DSE 2002) 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne, The birds move between the three sites. Victoria 3002 Australia Description and Distribution The Helmeted Honeyeater (Lichenostomus The three coastal subspecies of the Yellow- This publication may be of melanops cassidix Gould 1867) is a songbird tufted Honeyeater are thought to have assistance to you but the with striking black, yellow and olive become geographically and genetically State of Victoria and its plumage. It is the largest of the four isolated from each other as a result of their employees do not guarantee subspecies of the Yellow-tufted Honeyeater sedentary habits. However, geographic that the publication is (L. melanops): the average total length and isolation and genetic differentiation between without flaw of any kind or weight of mature males is in excess of 200 L. m. cassidix and L. m. gippslandicus has yet is wholly appropriate for to be demonstrated conclusively. L. m. your particular purposes mm and 32 g. It is very similar to the race L. gippslandicus ranges from near Warburton in and therefore disclaims all m. gippslandicus, except that in the liability for any error, loss Helmeted Honeyeater the forehead tuft of Victoria, south and east of the Great or other consequence which feathers is more conspicuous and the Dividing Range to Merrimbula, New South may arise from you relying transition is abrupt between the colours of Wales. -

Helmeted Honeyeater (Yellow-Tufted Honeyeater: West Gippsland)

RECOVERY OUTLINE Helmeted Honeyeater (Yellow-tufted Honeyeater: west Gippsland) 1 Family Meliphagidae 2 Scientific name Lichenostomus melanops cassidix (Gould, 1867) 3 Common name Helmeted Honeyeater 4 Conservation status Critically Endangered: B1+2c, D 5 Reasons for listing This species is found in a single area of about 5 km2 (Critically Endangered: B1) and the quality of habitat is still declining (B2c). The wild population also contains fewer than 50 mature individuals (D). Estimate Reliability Extent of occurrence 5 km2 high trend stable high Area of occupancy 5 km2 high trend stable high No. of breeding birds 48 high trend increasing high 9 Ecology No. of sub-populations 1 high The Helmeted Honeyeater inhabits streamside lowland Generation time 5 years medium swamp forest. It is rarely found far from water and all 6 Infraspecific taxa current birds live in closed riparian forest dominated L. m. melanops (south-eastern Australia, south or east of by Mountain Swamp Gum Eucalyptus camphora where the Great Dividing Ra.) and L. m. meltoni (south- they feed among the decorticating bark (Pearce et al., eastern Australia, inland slopes of the Great Dividing 1994). Some pairs feed on Swamp Gum E. ovata in Ra.). Both are phenotypically and genetically distinct winter and they will also use patchy thickets of Scented from the Helmeted Honeyeater (Blackney and Paperbark Melaleuca squarrosa, Woolly Tea-tree Menkhorst, 1993, Damiano, 1996). Leptospermum lanigerum, Prickly Tea-tree L. juniperinum and sedges (Backhouse, 1987, Blackney and 7 Past range and abundance Menkhorst, 1993, Moysey, 1997, Menkhorst et al., Endemic to Victoria. Scattered distribution through 1999).