David Lynch the Factory Photographs Petra Giloy-Hirtz Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eraserhead and Masculinity by Dylan Price

Eraserhead and Masculinity With a “nebbish” young man in the lead role, by Dylan Price David Lynch’s Eraserhead followed this insecurity, leading its viewers into the disturbingly relat- Dylan Price is a Psychology—Pre-Med major from able tale of Henry Spencer, his not-so-loving wife Lawton, Oklahoma who wrote this essay in the “Modern Mary X, and their grotesque progeny (Gross d12). Monsters” class taught by David Long. Supported by appearances from the Beautiful Girl Across the Hall, the Lady in the Radiator, the X The Sordid Seventies, the Scary Seventies, the Sur- family, and bookend cameos from the Man in the real Seventies—all such alliterative aliases could Planet, the flm portrays Henry and his family in be reasonably ascribed to the decade that former a surreal, Lynchian2 kitchen-sink reality, shining a President Jimmy Carter famously believed to have light of inevitability on the shadowy conceptualiza- inspired a “crisis of confdence” (Graebner 157). tion of gender roles in the 1970s and the perceived This was a time when the sexual revolution and the castration of the male persona. women’s liberation movement drew the ire of more Eraserhead is a unique flm, even among traditionally minded men nationwide, with the Lynch’s strange flmography. It is probably the male gaze giving the evil eye to the women who most perplexing flm of his career, and its grip decided that they had what it takes to do the jobs on reality is tenuous at best. Like most flms that men had already been doing. Men, traditionally Lynch directed, it has been pulled apart and dis- the sole source of income—the so-called bread- sected repeatedly, but it still maintains an air of winners—would potentially now have to compete mystery, often considered to be so disturbing that with their wives, their neighbors, their neighbors’ many would prefer to latch on to the frst inter- wives, and any other woman who had in her head pretation that they agree with and move on. -

The Interview Project Sur : Un Road Trip Halluciné Au Fond De L’Amérique, Avec Le Plus Grand Cinéaste Américain Comme Guide

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 14:20 24 images The Interview Project sur www.davidlynch.com Un road trip halluciné au fond de l’Amérique, avec le plus grand cinéaste américain comme guide Pierre Barrette États de la nature, états du cinéma Numéro 144, octobre–novembre 2009 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/25102ac Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (imprimé) 1923-5097 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Barrette, P. (2009). The Interview Project sur www.davidlynch.com : un road trip halluciné au fond de l’Amérique, avec le plus grand cinéaste américain comme guide. 24 images, (144), 4–5. Tous droits réservés © 24/30 I/S, 2009 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ ACTUALITES THE INTERVIEW PROJECT SUR WWW.DAVIDLYNCH.COM Un road trip halluciné au fond de l'Amérique, avec le plus grand cinéaste américain comme guide par Pierre Barrette La météo donnée par David Lynch sur www.davidlynch.com avid Lynch est probablement le et de diffusion qui correspond parfaitement contres de la petite équipe engagée dans un plus pro-Web des cinéastes : son à l'esprit de chercheur indépendant qui le road trip de plusieurs mois, de la Californie à D site, davidlynch.com, est un modèle caractérise. -

La Dernière Frontière Du Cinéma Damien Detcheberry

Document generated on 09/26/2021 10:26 p.m. 24 images La dernière frontière du cinéma Damien Detcheberry David Lynch – Au carrefour des mondes Number 184, October–November 2017 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/87067ac See table of contents Publisher(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (print) 1923-5097 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Detcheberry, D. (2017). La dernière frontière du cinéma. 24 images, (184), 6–10. Tous droits réservés © 24/30 I/S, 2017 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ David Lynch – Au carrefour des mondes LA DERNIÈRE FRONTIÈRE DU CINÉMA par Damien Detcheberry Peinture, Mountain With Eye lithographie sur papier japonais (2009) et ouverture de The Elephant Man (1980) « Il est difficile de dire si Lynch est effectivement arrivé à la fin de son œuvre cinématographique1. » Ce commen- taire, tiré de l’ouvrage accompagnant l’exposition que la Fondation Cartier (Paris) a consacrée à David Lynch en 2007, résume bien les interrogations légitimes des admirateurs du réalisateur face au hiatus cinématographique qui a suivi la sortie d’Inland Empire (2006), et à l’explosion soudaine de créations courtes, d’œuvres vidéo, documentaires, interactives, voire tout bonnement inclassables, qui ont été proposées au public depuis le début des années 2000. -

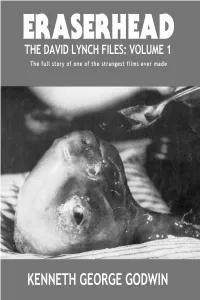

ERASERHEAD the David Lynch Files: Volume 1

ERASERHEAD The David Lynch Files: Volume 1 Kenneth George Godwin This book is for sale at http://leanpub.com/lynch This version was published on 2016-02-12 This is a Leanpub book. Leanpub empowers authors and publishers with the Lean Publishing process. Lean Publishing is the act of publishing an in-progress ebook using lightweight tools and many iterations to get reader feedback, pivot until you have the right book and build traction once you do. © 1981, 1982 and 2015 Kenneth George Godwin To David Lynch, whose first feature changed the course of my life. Contents Introduction .......................... 1 Eraserhead: An Appreciation ................ 5 Introduction Spike In the summer of 1980, David Lynch’s first feature, Eraserhead, showed up at what was at the time Winnipeg’s main repertory cinema, The Festival on Sargent Avenue. The theatre was run by Greg Klimkiw (later Guy Maddin’s original producer) whom I knew from our in-print rivalry as film reviewers for the two University student newspapers – Greg for the University of Manitoba’s Man- itoban, and me for the University of Winnipeg’s Uniter. Although we had occasionally tossed barbs at each other, there was no actual animosity and when Greg took over the Festival, he handed me a “free lifetime pass”. The initial booking for Eraserhead was just for a weekend. Having read something about it in the previous year or two, I was eager to see it and went with a friend to the first showing. I was hooked from the opening image, found myself sucked into a remarkably dense, sustained imaginary world every detail of which fascinated me. -

The Mysterious World of David Lynch's Photographs of Old Factories

“The mysterious world of David Lynch’s photographs of old factories,” Far Out Magazine. 9 June 2019. Web. The mysterious world of David Lynch’s photographs of old factories David Lynch has made no secret of his infatuation with the industrial revolution throughout his career, a theme that has followed him around in multiple different artistic creations. Take, for example, Eraserhead, Lynch’s breakout project which is filmed in black and white and tells the story of Henry Spencer who is left to care for his grossly deformed child in a desolate industrial landscape. While creating Twin Peaks, Lynch took on a side project with the Brooklyn Academy of Music after they approached him and composer Angelo Badalamenti to create a theatrical piece of work. The result saw Lynch coin the phrase “Industrial Symphonies” while completing his 1990 avant-garde musical play Industrial Symphony No. 1: The Dream of the Broken Hearted. The factories of his film The Elephant Man, the sawmill in Twin Peaks and the lawn mower in The Straight Story all relate back to the industrial revolution theme that Lynch has carried along with him throughout his creative journey. Making this topic more literal, Lynch made more of his interest in photography and travelled to northern England to take photos of the degrading industrial landscape. “Well…if you said to me, ‘Okay, we’re either going down to Disneyland or we’re going to see this abandoned factory,’ there would be no choice,” Lynch once in an interview. “I’d be down there at the factory. I don’t really know why. -

Lynched the Short Films of David Lynch by Megan Spencer

Lynched The short films of David Lynch by Megan Spencer Published in .Cent Magazine (London), August 2010, the 'Intoxication' issue, guest edited by Richard Milward ___________________________ He’s a self-confessed caffeine, nicotine and donut addict. He’s also addicted to directing films, Transcendental Meditation and making art. And over the years in his shorts, animations, features and TV series, American fimmaker David Lynch has presented us with an array Portrait by Yuko Nasu of characters wrestling with addictions of their own, be it coffee (Agent Cooper, Twin Peaks), violence (Frank, Blue Velvet), mystery (Betty/Diane, Mulholland Drive), anger, (Randy, Dumbland) and beyond. Lynch’s work seems to be born from if not addiction, then compulsion. Prolific in his output, when he’s not painting, writing books, taking photos, speaking at film festivals and conferences, meditating, animating, directing TV and features, or uploading his latest ‘weather report’ onto his website… Well there aren’t many hours left in the day. However addicted to words the filmmaker is not. Perhaps a ‘war with words’ is too harsh a depiction of the struggle David Lynch appears to go through when he speaks about his work. But if you have heard him talk you will know that speaking doesn’t come easily to the director; not his preferred mode of communication. Perhaps it might be fairer to say that words are Lynch’s ‘second language’, with images, pictures and sounds romping it in in first place. From Eraserhead (1976) through to Inland Empire (2006), neither are words tantamount in his features. Lynch doesn’t write a script like others. -

A Tortuous Q&A with David Lynch on the Inspiration For

"I’m Happier and Happier": A Tortuous Q&A With David Lynch on the Inspiration For His New Paintings by Ben Davis 27/03/12 10:27 AM EDT David Lynch (Photo Courtesy Père Ubu via Flickr) Who would have thought that an interview with David Lynch would be so unsettling? Lynch, who already has about as much cachet as any living American filmmaker could, seems lately to have expanded his preoccupations decisively beyond film, having branched out into pop music with his recent album "Crazy Clown Time," and even nightclub design with the opening of his Club Silencio in Paris last year. His efforts as a visual artist, however, stretch back decades, running in tandem with his more famous career as an auteur. It was as an art student at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts that he first discovered the moving image, making the short animated film "Six Men Getting Sick" (1966) to give life to one of his paintings. Not so long ago, he had a full-blown career retrospective of his painting and sculpture at the Fondation Cartier in Paris. His solo exhibition at the Upper East Side's Jack Tilton gallery, however, is his first gallery outing in New York in decades. The modestly sized show encompasses a series of newish paintings, some on cardboard panels and with bulky gold frames, some with Christmas tree lights poking through the background. The protagonists of these paintings are generally boys, often with bulbous or misshapen body parts, often frozen in the middle of some absurd moment of self-mutilation or savagery. -

Industrialism and the Futility of Man in Eraserhead Jessica White

Industrialism and the Futility of Man in Eraserhead Jessica White This paper was written for Dr. Brevik’s David Lynch course. In the 1977 cult classic Eraserhead, director David Lynch uses a series of stylistic techniques, characters, and plot to convey the futility of man in a world that has become mechanized and industrialized. J.D. Lafrance comments that “Eraserhead is an urban nightmare set in an industrial wasteland ‘reminiscent of the paintings of the Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger,’ whose works contain images of decaying biological matter and people trapped in machinery, becoming one with industry, much like Lynch’s film with its bleak landscapes of buildings and factories with no signs of nature present” (Lafrance). Early in the film we see the main character Henry Spencer walking through this dreary landscape crossing over a train track between what look like polluted factory buildings. Henry crosses over murky puddles of waste from the nearby factories and mounds of dirt. The train track itself could be a representation of the Industrial Revolution, a period in which the use of steam locomotives for the transport of textiles and other goods became extremely important for the development of the country. In the film, the sound of a train’s screeching wheels and constant clacking against tracks can be heard at various times; especially in the home of Henry’s wife Mary, who appears to live directly next to a train depot. The sounds resonate in the background along with other mechanical music such as the clanking of gears and grinds. Lynch may have chosen to shoot Eraserhead in black and white to emphasize the darkness and bleakness of this industrial town. -

Call for Submissions

David Lynch Art Show at The Loft Cinema CALL FOR SUBMISSIONS David Lynch famously described his debut feature film, the 1977 cult classic Eraserhead, as “a dream of dark and troubling things,” and there is no better phrase one could use to conjure up the mysterious, disturbing and oddly hilarious world of this one-of-a-kind cinematic artist. Embracing the absurd and the surreal with equal affection, Lynch’s endlessly re-watchable films are indeed “wild at heart and weird on top” - unpredictable road trips into the twisted Emerald City of the subconscious, populated by the doomed, the damned and the downright bizarre. From the Norman Rockwell on Acid kink of Blue Velvet to the Soap Opera from Hell shenanigans of Twin Peaks to the Mind- Blowing Tinseltown strangeness of Mulholland Drive, the cinema of David Lynch is like a “damn fine cup of coffee” – dark, addictive and guaranteed to keep you up at night. As part of The Loft Cinema’s September celebration of the films of David Lynch, we’re looking for YOUR personal take on everything Lynchian, and we’re now accepting submissions to our one-night-only, sure-to-be epic David Lynch Art Show. The Red Room awaits … Entry Deadline: September 14, 2015 Date of Exhibition: September 23, 2015 Reception: September 23, 2015, 6:00-7:00pm Reception followed by Mulholland Drive at 7:00pm Exhibition Venue: The Loft Cinema Back Lot* Submission and Media Guidelines: Work must feature David Lynch as subject or inspiration Images of work must be submitted in JPG format. -

Rogers, Holly. 2019. the Audiovisual Eerie: Transmediating Thresholds in the Work of David Lynch

Rogers, Holly. 2019. The Audiovisual Eerie: Transmediating Thresholds in the Work of David Lynch. In: Carol Vernallis; Holly Rogers and Lisa Perrott, eds. Transmedia Directors: Artistry, Industry and the New Audiovisual Aesthetics. New York: Bloomsbury, pp. 241-270. ISBN 9781501341007 [Book Section] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/26594/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] Transmedia Directors, ed. Holly Rogers, Carol Vernallis, Lisa Perrott (Bloomsbury, 2019). The Audiovisual Eerie: Transmediating Thresholds in the Work of David Lynch Holly Rogers David Lynch’s sonic resonances echo through projects and media. Pulsating room tone, eerie acousmêtre, electronic wash, static drones, thwarted resolutions and remediated retro textures frequently trouble the image, while imploding lip-syncs violently tear sound from sight and disembodied noises lead attention beyond the edge of the screen. Lynch’s soundscapes point beyond themselves. They are disruptive, bleeding between film, television, internet and music video work, resonating in the unseen spaces that surround each narrative centre before overflowing into ancillary worlds. These liminal spaces are occupied by sound alone and mark the threshold not only between projects, but also between music and image, inside and out, real and imagined. -

Eraserhead by David Sterritt “The B List: the National Society of Film Critics on the Low-Budget Beauties, Genre-Bending Mavericks, and Cult Classics We Love”

Eraserhead By David Sterritt “The B List: The National Society of Film Critics on the Low-Budget Beauties, Genre-Bending Mavericks, and Cult Classics We Love” Reprinted by permission of the author “Eraserhead” didn’t invent the midnight movie show. That honor goes to Alejandro Jodorowsky’s savage “El Topo” and George Romero’s chillers “Night of the Living Dead” and “Martin,” which pioneered the field in the early to middle 1970s. Nor did David Lynch’s genre- bending melodramedy skyrocket to suc- cess when it did make its witching-hour debut, courtesy of an enterprising Green- wich Village theater that took a chance with it in 1977. Lynch later recalled an opening-night crowd of twenty-five peo- Jack Nance stars as Henry in David Lynch’s idiosyncratic genre bender. ple, and reviews were lukewarm at best. Courtesy Library of Congress But momentum grew as word-of-mouth enthusiasm spread for the newborn in their apartment. And it’s quite a newborn — complete with rumors that the sound track emitted an — armless, legless, shrouded in bandage from the neck inaudible drone that tapped into the audience’s unconscious, down, and emitting plaintive cries from the gaping mouth in as if only subliminal trickery could account for the picture’s its turtle-like face. Stressed beyond endurance, Mary goes uncanny power. By the end of the ‘70s it had scored a mid- back to her parents, leaving Henry to tend the little once. night hit in San Francisco and started a Los Angeles run that When the infant pushes him over the edge as well, he resorts lasted into 1981; by 1983 it had played everywhere from to self-protective violence. -

ART of the RIDICULOUS SUBLIME on David Lynch’S Lost Highway Slavoj Zizek

THE ART OF THE RIDICULOUS SUBLIME On David Lynch’s Lost Highway Slavoj Zizek CONTENTS Introduction: The Ridiculous, Sublime Art of Slavoj Zizek BY MAREK WIECZOREK / viii THE ART OF THE RIDICULOUS SUBLIME: On David Lynch’s Lost Highway BY SLAVOJ Zizek I page 3 I The Inherent Transgression / page 4 2 The Feminine Act / page 8 3 Fantasy Decomposed / page 13 4 The Three Scenes / page 18 5 Canned Hatred / page 23 6 Fathers, Fathers Everywhere / page 28 7 The End of Psychology / page 32 8 Cyberspace Between Perversion and Trauma / page 36 9 The Future Antérieur in the History of Art / page 39 10 Constructing the Fundamental Fantasy / page 41 The Ridiculous, Sublime Art of Slavoj Zizek Marek Wieczorek Slavoj Zizek is one of the great minds of our time. Commentators have hailed the Slovenian thinker as “the most formidably brilliant exponent of psycho- analysis, indeed of cultural theory in general, to have emerged in Europe for some decades.”1 The originality of Zizek’s contribution to Western intellectual history lies in his extraordinary fusion of Lacanian psychoanalytic theory, continental phi- losophy (in particular his anti-essentialist readings of Hegel), and Marxist po- litical theory. He lucidly illustrates this sublime thought with examples drawn from literary and popular culture, including not only Shakespeare, Wagner, or Kafka, but also film noir, soap operas, cartoons, and dirty jokes, which of- ten border on the ridiculous. “I am convinced of my proper grasp of some Lacanian concept, ”Zizek writes, “only when I can translate it successfully into the inherent imbecility of popular culture.”2 The Art of the Ridiculous Sublime: On David Lynch’s Lost Highway characteristically offers a flamboyant parade of topics that reaches far beyond the scope of Lynch’s movie, delving into film theory, ethics, politics, and cyberspace.