From Pitch to Production in Hollywood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sean Callery

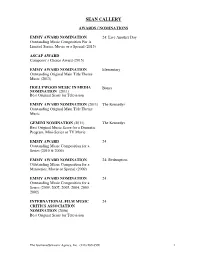

SEAN CALLERY AWARDS / NOMINATIONS EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24: Live Another Day Outstanding Music Composition For A Limited Series, Movie or a Special (2015) ASCAP AWARD Composer’s Choice Award (2015) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION Elementary Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music (2013) HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA Bones NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score for Television EMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2011) The Kennedys Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music GEMINI NOMINATION (2011) The Kennedys Best Original Music Score for a Dramatic Program, Mini-Series or TV Movie EMMY AWARD 24 Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (2010 & 2006) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24: Redemption Outstanding Music Composition for a Miniseries, Movie or Special (2009) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24 Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (2009, 2007, 2005, 2004, 2003, 2002) INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC 24 CRITICS ASSOCIATION NOMINATION (2006) Best Original Score for Television The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 SEAN CALLERY TELEVISION SERIES JESSICA JONES (series) Melissa Rosenberg, Jeph Loeb, exec. prods. ABC / Marvel Entertainment / Tall Girls Melissa Rosenberg, showrunner BONES (series) Barry Josephson, Hart Hanson, Stephen Nathan, Fox / 20 th Century Fox Steve Bees, exec. prods. HOMELAND (pilot & series) Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Avi Nir, Gideon Showtime / Fox 21 Raff, Ran Telem, exec. prods. ELEMENTARY (pilot & series) Carl Beverly, Robert Doherty, Sarah Timberman, CBS / Timberman / Beverly Studios Craig Sweeny, exec. prods. MINORITY REPORT (pilot & series) Kevin Falls, Max Borenstein, Darryl Frank, 20 th Century Fox Television / Fox Justin Falvey, exec. prods. Kevin Falls, showrunner MEDIUM (series) Glenn Gordon Caron, Rene Echevarria, Kelsey Paramount TV /CBS Grammer, Ronald Schwary, exec. prods. 24: LIVE ANOTHER DAY (event-series) Kiefer Sutherland, Howard Gordon, Brian 20 TH Century Fox Grazer, Jon Cassar, Evan Katz, Robert Cochran, David Fury, exec. -

DAN LEIGH Production Designer

(3/31/17) DAN LEIGH Production Designer FILM & TELEVISION DIRECTOR COMPANIES PRODUCERS “GYPSY” Sam Taylor-Johnson Netflix Rudd Simmons (TV Series) Scott Winant Universal Television Tim Bevan “THE FAMILY” Paul McGuigan ABC David Hoberman (Pilot / Series) Mandeville Todd Lieberman “FALLING WATER” Juan Carlos Fresnadillo USA Gale Anne Hurd (Pilot) Valhalla Entertainment Blake Masters “THE SLAP” Lisa Cholodenko NBC Rudd Simmons (TV Series) Michael Morris Universal Television Ken Olin “THE OUTCASTS” Peter Hutchings BCDF Pictures Brice Dal Farra Claude Dal Farra “JOHN WICK” David Leitch Thunder Road Pictures Basil Iwanyk Chad Stahelski “TRACERS” Daniel Benmayor Temple Hill Entertainment Wyck Godfrey FilmNation Entertainment D. Scott Lumpkin “THE AMERICANS” Gavin O'Connor DreamWorks Television Graham Yost (Pilot) Darryl Frank “VAMPS” Amy Heckerling Red Hour Adam Brightman Lucky Monkey Stuart Cornfeld Molly Hassell Lauren Versel “PERSON OF INTEREST” Various Bad Robot J.J. Abrams (TV Series) CBS Johanthan Nolan Bryan Burk Margot Lulick “WARRIOR” Gavin O’Connor Lionsgate Greg O’Connor Solaris “MARGARET” Kenneth Lonergan Mirage Enterprises Gary Gilbert Fox Searchlight Sydney Pollack Scott Rudin “BRIDE WARS” Gary Winick Firm Films Alan Riche New Regency Pictures Peter Riche Julie Yorn “THE BURNING PLAIN” Guillermo Arriaga 2929 Entertainment Laurie MacDonald Walter F. Parkes SANDRA MARSH & ASSOCIATES Tel: (310) 285-0303 Fax: (310) 285-0218 e-mail: [email protected] (3/31/17) DAN LEIGH Production Designer ---2-222---- FILM & TELEVISION COMPANIES -

The Rise of a Confident Hollywood: Risk and the Capitalization of Cinema’, Review of Capital As Power, Vol

THE RISE OF A CONFIDENT HOLLYWOOD Suggested citation: James McMahon (2013), ‘The Rise of a Confident Hollywood: Risk and the Capitalization of Cinema’, Review of Capital as Power, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 23-40. The Rise of a Confident Hollywood: Risk and the Capitalization of Cinema1 JAMES MCMAHON Nature ceased to be inscrutable, subject to demonic incursions from another world: the very essence of Nature, as freshly conceived by the new scientists, was that its sequences were orderly and therefore predictable: even the path of a comet could be charted through the sky. It was on the model of this external physical order that men began systematically to reorganize their minds and their practical activities: this carried further, and into every department, the precepts and practices empirically fostered by bourgeois finance. Like Emerson, men felt that the universe itself was fulfilled and justified, when ships came and went with the regularity of heavenly bodies. - Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization he Hollywood film business, like any other business enterprise, operates according to the logic of capitalization. Capitalization in an instrumental logic T that is forward-looking in its orientation. Capitalization expresses the present value of an expected stream of future earnings. And since the earnings of the Hollywood film business depend on cinema and mass culture in general, we can say that the current fortunes of the Hollywood film business hinge on the future of cinema and mass culture. The ways in which pleasure is sublimated through mass culture, and how these ways may evolve in the future, have a bearing on the valuation of Hollywood’s control of filmmaking. -

Representations and Discourse of Torture in Post 9/11 Television: an Ideological Critique of 24 and Battlestar Galactica

REPRESENTATIONS AND DISCOURSE OF TORTURE IN POST 9/11 TELEVISION: AN IDEOLOGICAL CRITIQUE OF 24 AND BATTLSTAR GALACTICA Michael J. Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2008 Committee: Jeffrey Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin ii ABSTRACT Jeffrey Brown Advisor Through their representations of torture, 24 and Battlestar Galactica build on a wider political discourse. Although 24 began production on its first season several months before the terrorist attacks, the show has become a contested space where opinions about the war on terror and related political and military adventures are played out. The producers of Battlestar Galactica similarly use the space of television to raise questions and problematize issues of war. Together, these two television shows reference a long history of discussion of what role torture should play not just in times of war but also in a liberal democracy. This project seeks to understand the multiple ways that ideological discourses have played themselves out through representations of torture in these television programs. This project begins with a critique of the popular discourse of torture as it portrayed in the popular news media. Using an ideological critique and theories of televisual realism, I argue that complex representations of torture work to both challenge and reify dominant and hegemonic ideas about what torture is and what it does. This project also leverages post-structural analysis and critical gender theory as a way of understanding exactly what ideological messages the programs’ producers are trying to articulate. -

International Casting Directors Network Index

International Casting Directors Network Index 01 Welcome 02 About the ICDN 04 Index of Profiles 06 Profiles of Casting Directors 76 About European Film Promotion 78 Imprint 79 ICDN Membership Application form Gut instinct and hours of research “A great film can feel a lot like a fantastic dinner party. Actors mingle and clash in the best possible lighting, and conversation is fraught with wit and emotion. The director usually gets the bulk of the credit. But before he or she can play the consummate host, someone must carefully select the right guests, send out the invites, and keep track of the RSVPs”. ‘OSCARS: The Role Of Casting Director’ by Monica Corcoran Harel, The Deadline Team, December 6, 2012 Playing one of the key roles in creating that successful “dinner” is the Casting Director, but someone who is often over-looked in the recognition department. Everyone sees the actor at work, but very few people see the hours of research, the intrinsic skills, the gut instinct that the Casting Director puts into finding just the right person for just the right role. It’s a mix of routine and inspiration which brings the characters we come to love, and sometimes to hate, to the big screen. The Casting Director’s delicate work as liaison between director, actors, their agent/manager and the studio/network figures prominently in decisions which can make or break a project. It’s a job that can't garner an Oscar, but its mighty importance is always felt behind the scenes. In July 2013, the Academy of Motion Pictures of Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) created a new branch for Casting Directors, and we are thrilled that a number of members of the International Casting Directors Network are amongst the first Casting Directors invited into the Academy. -

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006

First-Run Smoking Presentations in U.S. Movies 1999-2006 Jonathan R. Polansky Stanton Glantz, PhD CENTER FOR TOBAccO CONTROL RESEARCH AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94143 April 2007 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Smoking among American adults fell by half between 1950 and 2002, yet smoking on U.S. movie screens reached historic heights in 2002, topping levels observed a half century earlier.1 Tobacco’s comeback in movies has serious public health implications, because smoking on screen stimulates adolescents to start smoking,2,3 accounting for an estimated 52% of adolescent smoking initiation. Equally important, researchers have observed a dose-response relationship between teens’ exposure to on-screen smoking and smoking initiation: the greater teens’ exposure to smoking in movies, the more likely they are to start smoking. Conversely, if their exposure to smoking in movies were reduced, proportionately fewer teens would likely start smoking. To track smoking trends at the movies, previous analyses have studied the U.S. motion picture industry’s top-grossing films with the heaviest advertising support, deepest audience penetration, and highest box office earnings.4,5 This report is unique in examining the U.S. movie industry’s total output, and also in identifying smoking movies, tobacco incidents, and tobacco impressions with the companies that produced and/or distributed the films — and with their parent corporations, which claim responsibility for tobacco content choices. Examining Hollywood’s product line-up, before and after the public voted at the box office, sheds light on individual studios’ content decisions and industry-wide production patterns amenable to policy reform. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. Adam Ant=English musician who gained popularity as the Amy Adams=Actress, singer=134,576=68 AA lead singer of New Wave/post-punk group Adam and the Amy Acuff=Athletics (sport) competitor=34,965=270 Ants=70,455=40 Allison Adler=Television producer=151,413=58 Aljur Abrenica=Actor, singer, guitarist=65,045=46 Anouk Aimée=Actress=36,527=261 Atif Aslam=Pakistani pop singer and film actor=35,066=80 Azra Akin=Model and actress=67,136=143 Andre Agassi=American tennis player=26,880=103 Asa Akira=Pornographic act ress=66,356=144 Anthony Andrews=Actor=10,472=233 Aleisha Allen=American actress=55,110=171 Aaron Ashmore=Actor=10,483=232 Absolutely Amber=American, Model=32,149=287 Armand Assante=Actor=14,175=170 Alessandra Ambrosio=Brazilian model=447,340=15 Alan Autry=American, Actor=26,187=104 Alexis Amore=American pornographic actress=42,795=228 Andrea Anders=American, Actress=61,421=155 Alison Angel=American, Pornstar=642,060=6 COMPLETEandLEFT Aracely Arámbula=Mexican, Actress=73,760=136 Anne Archer=Film, television actress=50,785=182 AA,Abigail Adams AA,Adam Arkin Asia Argento=Actress, film director=85,193=110 AA,Alan Alda Alison Armitage=English, Swimming=31,118=299 AA,Alan Arkin Ariadne Artiles=Spanish, Model=31,652=291 AA,Alan Autry Anara Atanes=English, Model=55,112=170 AA,Alvin Ailey ……………. AA,Amedeo Avogadro ACTION ACTION AA,Amy Adams AA,Andre Agasi ALY & AJ AA,Andre Agassi ANDREW ALLEN AA,Anouk Aimée ANGELA AMMONS AA,Ansel Adams ASAF AVIDAN AA,Army Archerd ASKING ALEXANDRIA AA,Art Alexakis AA,Arthur Ashe ATTACK ATTACK! AA,Ashley -

HBO and the HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, the HISTORICAL FILM, and PUBLIC HISTORY at WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the Facul

HBO AND THE HOLOCAUST: CONSPIRACY, THE HISTORICAL FILM, AND PUBLIC HISTORY AT WANNSEE Nicholas K. Johnson Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University December 2016 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee __________________________________ Raymond J. Haberski, Ph.D., Chair __________________________________ Thorsten Carstensen, Ph.D. __________________________________ Kevin Cramer, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank the members of my committee for supporting this project and offering indispensable feedback and criticism. I would especially like to thank my chair, Ray Haberski, for being one of the most encouraging advisers I have ever had the pleasure of working with and for sharing his passion for film and history with me. Thorsten Carstensen provided his fantastic editorial skills and for all the times we met for lunch during my last year at IUPUI. I would like to thank Kevin Cramer for awakening my interest in German history and for all of his support throughout my academic career. Furthermore, I would like to thank Jason M. Kelly, Claudia Grossmann, Anita Morgan, Rebecca K. Shrum, Stephanie Rowe, Modupe Labode, Nancy Robertson, and Philip V. Scarpino for all the ways in which they helped me during my graduate career at IUPUI. I also thank the IUPUI Public History Program for admitting a Germanist into the Program and seeing what would happen. I think the experiment paid off. -

Writing Dialogue & Advice from the Pros

Writing Dialogue & Advice from the Pros Writing great dialogue is considered an art form. Listening to real-life conversations, watching award- winning films, and learning from the masters will help you craft dialogue that shines on the page. The following writing thoughts and advice are excerpts from Karl Iglesias’ book, The 101 Habits of Highly Successful Screenwriters. Enjoy! ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Writing Unrealistic and Boring Dialogue In real life, dialogue is mostly polite conversation. In film, polite conversation is considered bad dialogue, unless it’s witty, sarcastic, or has a unique voice. The reason is that polite chat lacks tension, and tension is the key to dramatic storytelling. As Alfred Hitchcock once said, “Drama is real life with all the boring parts cut out of it.” The key to good dialogue is to understand that it’s not conversation, it’s action. What characters say in a scene should be said to get what they want in the scene. And to determine whether or not your dialogue sounds realistic, read it out loud. Garrison Keillor once advised, “If you read your work out loud, it helps to know what’s bad.” Try it. It works. Dialogue always sounds better in your head. Better to be embarrassed in your room than on the set. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Read Your Dialogue Out Loud Writing authentic, well-crafted dialogue that sparkles, individualizes characters, and entertains the reader is the ultimate challenge for screenwriters, who otherwise may have solid script elements. It’s crucial to attracting talent, which can green-light your script. Writing great dialogue can also sell the writer, for those who excel in this area are highly sought after to the tune of six figures per week for dialogue rewrites. -

October 2019

FILMS RATED/CLASSIFIED From 01 Oct 2019 to 31 Oct 2019 Films and Trailers FILM TITLE DIRECTOR RUN TIME DATE APPROVED DESCRIPTION MEDIA NAME #AnneFrank. Parallel Stories Sabina Fedeli/Anna 2.07 22/10/2019 PG Trailer Migotto 1917 Sam Mendes 2.27 15/10/2019 M Trailer 3 From Hell Rob Zombie 115.49 18/10/2019 R18 Graphic violence, sexual violence, horror & offensive language Film - DCP Abominable Jill Culton, Todd 97 24/10/2019 G Film - DVD Wilderman Ad Astra James Gray 122.55 8/10/2019 M Violence, offensive language & content that may disturb Film - DVD Addams Family, The Greg Tiernan, 86.58 17/10/2019 PG Coarse language Film - DCP Conrad Vernon Aeronauts, The Tom Harper 100.23 8/10/2019 PG Film - DCP All at Sea Robert Young 88.2 10/10/2019 M Film - DCP Am Cu Ce Pride Hannah 19 25/10/2019 PG Offensive language Film - DCP Weissenborn André Rieu: 70 Years Young André Rieu and 1 15/10/2019 G Trailer Michael Wiseman Angel Has Fallen Ric Roman Waugh 121 7/10/2019 R16 Violence & offensive language Film - Harddrive Arctic Justice Aaron Woodley 92 24/10/2019 G Film - DCP Ardab Mutiyaran Manav Shah 139.3 15/10/2019 PG Violence & coarse language Film - DCP At Last Yiwei Liu 1.05 22/10/2019 M Trailer Badlands Terrence Malick 93.37 15/10/2019 M Violence Film - DCP Bala Amar Kaushik 2.47 22/10/2019 M Sexual references Trailer Barefoot Bandits, The: Behind the Voices Ryan Cooper, Alex 4.56 4/10/2019 G Film - DCP Leighton, Tim Evans Barefoot Bandits, The: Glow Your Own Way Comp Ryan Cooper, Alex 0.31 4/10/2019 G Film - DCP Leighton, Tim Evans For Further -

Gus Van Sant Retrospective Carte B

30.06 — 26.08.2018 English Exhibition An exhibition produced by Gus Van Sant 22.06 — 16.09.2018 Galleries A CONVERSATION LA TERRAZA D and E WITH GUS VAN SANT MAGNÉTICA CARTE BLANCHE PREVIEW OF For Gus Van Sant GUS VAN SANT’S LATEST FILM In the months of July and August, the Terrace of La Casa Encendida will once again transform into La Terraza Magnética. This year the programme will have an early start on Saturday, 30 June, with a double session to kick off the film cycle Carte Blanche for Gus Van Sant, a survey of the films that have most influenced the American director’s creative output, selected by Van Sant himself filmoteca espaÑola: for the exhibition. With this Carte Blanche, the director plunges us into his pecu- GUS VAN SANT liar world through his cinematographic and musical influences. The drowsy, sometimes melancholy, experimental and psychedelic atmospheres of his films will inspire an eclectic soundtrack RETROSPECTIVE that will fill with sound the sunsets at La Terraza Magnética. La Casa Encendida Opening hours facebook.com/lacasaencendida Ronda de Valencia, 2 Tuesday to Sunday twitter.com/lacasaencendida 28012 Madrid from 10 am to 10 pm. instagram.com/lacasaencendida T 902 430 322 The exhibition spaces youtube.com/lacasaencendida close at 9:45 pm vimeo.com/lacasaencendida blog.lacasaencendida.es lacasaencendida.es With the collaboration of Cervezas Alhambra “When I shoot my films, the tension between the story and abstraction is essential. Because I learned cinema through films made by painters. Through their way of reworking cinema and not sticking to the traditional rules that govern it. -

1 AUDIO BOOKS, MUSIC and MOVIES at Reinert-Alumni Library

AUDIO BOOKS, MUSIC and MOVIES at Reinert-Alumni Library 3rd Quarter 2012 AUDIO BOOKS Chopra, Deepak. Muhammad : a story of the last prophet / by Deepak Chopra. Born into the factious world of war-torn Arabia, Muhammad's life is a gripping and inspiring story of one man's tireless fight for unity and peace. In a world where greed and injustice ruled, Muhammad created change by affecting hearts and minds. Just as the story of Jesus embodies the message of Christianity, Muhammad's life reveals the core of Islam. Deepak Chopra shares the life of Muhammad as never before, putting his teachings in a new light. BP75 .C46 2010AB 8 / by Dustin Lance Black ; [produced for the stage by the American Foundation for Equal Rights and Broadway Impact]. Uses actual court transcripts and first-hand interviews to bring to life the landmark federal trial challenging Proposition 8, a constitutional amendment that eliminated the rights of same-sex couples to marry in the state of California. PN1997.3.B53 E54 2012AB Fletcher, Susan, 1979- The highland witch [Audio Book in MP3 format] / by Susan Fletcher. 1692. Corrag--an accused witch--is imprisoned for her supposed involvement in a massacre she had no part in. As she tells her story to an Irish propagandist, she transforms both their lives. PR6106.L48 2011EAB Pelecanos, George P. What it was / George Pelecanos. Washington, D.C., 1972. Derek Strange has left the police department and set up shop as a private investigator. His former partner, Frank "Hound Dog" Vaughn, is still on the force. When a young woman comes to Strange asking for his help recovering a cheap ring she claims has sentimental value, the case leads him onto Vaughn's turf, where a local drug addict's been murdered, shot point-blank in his apartment.