Pascagoula Decoy Company Employees Operating the Duplicating Lathe Machines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page: 1 Great Oak Auctions & Decoys Unlimited Inc. Lot# Description 1 2

Great Oak Auctions & Decoys Unlimited Inc. Page: 1 Lot# Description 1 Pair of Black Ducks by Charles Moore Pair of Black Ducks by Charles Moore. One sleeper and one upright. One pictured. 200.00 - 400.00 2 Pair of Teal Decoys by Moore Pair of Teal Decoys by Moore in original paint and good condition. 200.00 - 300.00 3 Lot of 2 Racy Merganser Hen Decoys 2 Merganser Hen Decoys by John Mulak, with nicely carved crests and original paint. 1pictured. 100.00 - 200.00 4 Gadwal Drake by Lou Reineiri Gadwal Drake by noted folk artist Lou Reineiri. Original paint and condition. 100.00 - 200.00 5 No Lot 5a Swimming Merganser Drake Decoy by Nolan Swimming Merganser Drake Decoy by J.J. Nolan, dated 1985. 100.00 - 200.00 5b Perky Bufflehead Drake Decoy by Bob Berry Bufflehead Drake Decoy by Bob Berry Signed and dated 1985, in original paint with attached keel. 75.00 - 125.00 6 Wood Duck Drake Decoy by Herter Factory Wood Duck Drake By the Herter Factory, Waseca, MN in original condition. 100.00 - 200.00 Great Oak Auctions & Decoys Unlimited Inc. Page: 2 Lot# Description 6a Lot of 2. Sperry Black Duck and Mason Mallard Hen Lot of 2 decoys. Sperry Factory Black Duck, CT, and a Mason Factory Standard Grade Mallard Hen. 25.00 - 50.00 7 Carving of a Running Avocet Carving of an Avocet mounted on a wooden stand. Original paint and condition. 50.00 - 100.00 8 Lot of 2. A Golden Plover and Black Bellied Plover Carvings of a golden plover and a black bellied plover mounted on wooden stick bases. -

Local History Comes Alive at the February 17Th George Auction Service Event in Janesville, Wisconsin Forty-Six Years Later, Wisc

Online! Always On Time! Over One Million Hits www.auctionactionnews.com Help Recycle, Buy Antiques! March 31, 2015 Vol. 20 No. 35 News Periodical Mailed on March 25 Forty-Six Years Later, Wisconsin’s Original Decoy & Sporting Show Still Going Strong Article & photos by Brian Maloney It was way back in 1970 when a small group of decoy collectors got together and held the very first Wisconsin Decoy and Sporting Collectibles Show. And more than two generations later, the event is still going strong - the oldest event of its kind in the state. The show itself is a From Mike Trudel, a matched pair of one-day affair, but there are three days of spirited room-to-room trading Robert Swan goldeneye decoys, price preceding it, all open to the public. It’s the love of the hobby that brings tag $500. 920-293-4282 both the exhibitors and shoppers here to Oshkosh, Wisconsin, where you can find decoys both old and new, lots of other sporting-related collectibles, and an enthusiasm that’s just plain contagious! Continued on pages 6, 7 & 8 This Chuck Fitzgibbon original oil painting “Collins Marsh Memories” was a 2008 Ducks Unlimited contest winner, and was for sale here at the show for $3,000. 920-729-1968 Dan Coombe came with rare finds like From Wisconsin Sporting Collectibles, this rigmate pair of George Kessler a distinctive Frank Strey Wisconsin widgeons (circa-1930, $11,500) and canvasback drake decoy, asking price Robert Elliston blue-wing teal hen in fine $375. www.wisconsinsportingcollectibles.com original paint, $13,500. -

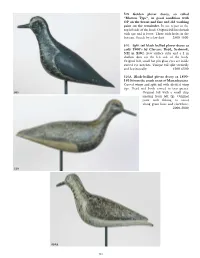

509. Golden Plover Decoy, So Called “Morton Type”, in Good Condition with OP on the Breast and Face and Old Working Paint on the Remainder

509. Golden plover decoy, so called “Morton Type”, in good condition with OP on the breast and face and old working paint on the remainder. In use repair to the top left side of the head. Original bill has shrunk with age and is loose. Three stick holes in the bottom. Struck by a few shot. 2500-4500 510. Split tail black-bellied plover decoy ca early 1900’s by Clarence Boyd, Seabrook, NH in XOC. Few surface rubs and a 1 in shallow dent on the left side of the body. Original bill, small hat pin glass eyes set inside carved eye notches. Unique tail split vertically and horizontally. 4500-6500 510A. Black-bellied plover decoy ca 1890- 1910 from the south coast of Massachusetts. Carved wings and split tail with divided wing tips. Head and body carved in two pieces. 509 Original bill with a small chip missing from left tip. Original paint with flaking to wood along grain lines and elsewhere. 2000-3000 510 510A 122 510B 510C 510D 510E 510B. Early, large, split tail willet ca 1900. Probably from 510D. Early two-piece solid bodied golden plover ca. 1880 Virginia or Cobb Island. Bill may be a replacement. Original from Nantucket, Mass. in vivid breeding plumage. Struck paint is very worn with the majority of the decoy worn to by either size 8 or 10 shot. In excellent original paint with in wood which has darkened with time. Chips from both ends of use wear usually found on 120 year old gunning shorebirds. the split tail. -

Center Facing

Online! Always On Time! Over One Million Hits www.auctionactionnews.com Help Recycle, Buy Antiques! August 28, 2018 Vol. 24 No. 07 News Periodical Mailed on August 22 Great Antiques and Collectibles at Younger Auction in Maryville, Missouri Article & photos by Younger Auction Co. On Saturday, May 5th, Younger Auction Co. held a sale for Ryan and Jennifer Pellersels at their gallery in Maryville, Missouri. For more than 50 years, Younger Auction Co. has been providing professional auction services in Northwest Missouri and beyond. This sale had some really neat items, covering a wide range of collectors. Continued on page 17 Arrowhead, 6 1/2 Inch Andrew County Missouri, it brought $325. Northwood Peacock & Urn Ice Cream Factory Sealed, Remington Umc. 12 Ga. Nitro Club, Bowl, Purple, sold for $230. Original Box, Full, 2 piece box brought $200. Sunday at Sandwich Antiques Show - Enjoy the Thrill of the Hunt Article & photos by Michelle Goltz On Sunday, July 8th one of many summer “Sunday at Sandwich Antiques Shows” was held at the fairgrounds located at 1401 Suydam Road in Sandwich, Illinois. Sunday at Sandwich is a place to see great treasures of the past. The drive was beautiful, so if you are interested in traveling to a great show, grab a friend or tell the hubby that he can golf at the Edgebrook Country Club while you shop! There are paths throughout the grounds full of vendors, as well as in some of the fair buildings. Dake Bakery Vendors came from all over Illinois and additional states also traveled to share their treasures! “ABC Soda Just remember that not all vendors have contacts so in order to Crackers” see their amazing inventory you must visit the shows. -

Art and Heritage of the Missouri Bootheel: a Resource Guide

of the Missouri Bootheel: AResource Guide Compiled and edited by C. Ray Brassieur and Deborah Bailey ~- ----------- .- of the Missouri Bootheel: AResource Guide Compiled and edited by C. Ray Brassieur and Deborah Bailey :".,1:":• • :~: •• : .: ..... : .. :••• :?: ... :" ~ .. .. .... .. .. ~ ...,; .......... " .. .. .. ~; ~ L.-- -.::w,~~.•'.::.• r-:-:-.....:......:..~--_-----J••.• : •• •••. :" •• :•• ...;, ~ ...... ........ .. :........: '... ::.. :.. I.: '.' I,'.. ... This design element is based on a variety of fish trap found in the Missouri Bootheel. Coverplwto by David Whitman. Abandoned sharecropper161uJ~1ZCQt" Wardell on New Madrid COUJ'lty Rd. 296on Marr:h 19, 1994. Copyright © 1995 The Curators of the University of Missouri Museum ofArt and Archaeology, Columbia, Missouri 65201 Printed and bound in the United States ofAmerica All rights reserved This publication, Art and Heritage ofthe Missouri Bootheel: A Resource Guide, and the coordinated exhibition, Art and Heritage ofthe Missouri Bootheel, have been organized by the Bootheel Underserved Arts Communities Project, which is cosponsored by the Museum ofArt and Archaeology and the State Historical Society of Missouri. The exhibition and its accompanying publication are made possible by generous grants from the Missouri Arts Council and the National Endowment of the Arts. The project is administered by the Missouri Folk Arts ProgramlMuseum ofArt and Archaeology in cooperation with the State Historical SocietylWestern Historical Manuscript Collection at the University of Missouri Columbia. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Art and heritage: a resource guide; edited by c. ray brassieur and deborah bailey includes bibliographic references ISBN 0-910501-30-0 -- 2-- Art and Heritage of the Missouri Bootheel: A Resource Guide Table of Contents Foreword Morteza Sajadian 4 How to Use This Guide 5 AIMS AND IDEAS: ENCOURAGING CREATIVITY IN THE BOOTHEEL The Bootheel Project: An Introduction C. -

Summer Decoy Auction Monday & Tuesday, July 13 - July 14, 2009 at the Cape Codder Resort and Hotel Hyannis, MA Telephone: (888) 297-2200

Decoys Unlimited, Inc. Theodore S. Harmon Ted and Judy Harmon of DECOYS UNLIMITED, INC. presents our SPECTACULAR Summer Decoy Auction Monday & Tuesday, July 13 - July 14, 2009 at the Cape Codder Resort and Hotel Hyannis, MA Telephone: (888) 297-2200 www.decoysunlimitedinc.net e-mail: [email protected] DECOY DEALER SHOW: Sunday, July 12, 12-9pm • Monday, July 13, 9-4pm PREVIEW: Sunday, July 12 , 6-9pm • Monday, July 13, 9-11am • Tuesday, July 13, 9-11am SALE: Monday, July 13, 11am • Tuesday, July 14, 11am Phone and Absentee Bidding Information See Directions in Back of Catalog For absentee or phone bidding please call Ted Harmon – (508) 362-2766 TERMINOLOGY: XOP - Excellent Original Paint XOC - Excellent Original Condition OP - Original Paint T/U - Touch Up For more information contact: Ted Harmon, P.O. Box 206, West Barnstable, MA 02668 • (508) 362-2766 See Conditions of Sale – Back of Catalog 1 Eric and Marie Lagerman Eric Lagerman grew up an enthusiastic student of all nature’s wonders on a farm near Rockford, Illinois. Although he had been a naturalist, hunter, fisherman and antiques collector all his life, his first decoys (a pair of Mason Detroit grade mallards, of course) were given to him by a friend when Eric was already in his fifties. He soon had over 500 of them. Eric and his wife, Marie, were regulars at the Drake, Oakbrook and Pheasant Run meetings of the Midwest Decoy Collectors Association, and all the Illinois old-timers will remember them. Mike became very interested in decoys in the late 1960’s and moved to upstate New York in 1970. -

Center Facing

Online! Always On Time! Over One Million Hits www.auctionactionnews.com Help Recycle, Buy Antiques! July 26, 2016 Vol. 22 No. 02 News Periodical Mailed on July 20 Fantastic Farm Toys Cross the Block at Matt Maring’s May 7th Auction Article & photos by Matt Maring On May 7th, 2016, Matt Maring Auction Co. held a large private col- lection auction out of Red Wing, Minnesota. The auction featured a lifetime 1991 Camaro RS Convertible, Auto, collection of vintage and newer farm pedal tractors, pedal cars, Ertl farm AM/FM Cassette, PW, PL, PM, 5.0L V8, toys, Franklin Mint, NASCAR, American muscle, Matchbox, vintage 17,725 Actual 1 Owner Miles, $12,000. dairy items, Collector as well as convertible cars. The auction took place at the Dodge Co. Fairgrounds in Kasson, MN. John Deere 10 Series 3 Hole Pedal Tractor w/Shifter, sold for $1,050. Dale Earnhardt JR 1/6sc Chevy Corvette, in original box (has been removed), it brought $900. John Deere Model A Pedal Case Pleasure King 30 Tractor, Metal Steering Continued on page 16 Pedal Tractor sold for $700. Wheel and Seat brought $800. The 51st Annual National Vintage Decoy & Sporting Collectibles Show – Granddaddy of Them All Article & photos by Brian Maloney It was way back in 1966 when a small group of decoy collec- tors got together and formed the Midwest Decoy Collectors Association - and held their first show in that same year. Now more than a half-century later, the Midwest Decoy Collectors Association has grown to be a truly international organization, with more than 1,000 members from all fifty states, Canada, and Mexico. -

DAY TWO - Tuesday, August 1, 2006

DAY TWO - Tuesday, August 1, 2006 425 425. Mason Factory Premier Grade blue winged teal 427. Mason Factory Detroit Grade Glass Eye mallard drake decoy in XOC. Few minor rubs to the bill tip. Seam hen decoy in XOC with two narrow bottom checks. No line visible. This is the Premier blue wing teal pictured on the weight. Original neck filler in good condition. Tiny dent second shelf down on the far right on page 483 in the Luckey under the bill, tiny mark on the left side of the face. See top of and Lewis book. The paint pattern features the desirable page 171, for a picture of this exact decoy in the Luckey and “double blue” paint. 4500-7500 Lewis book. 1000-1500 Pitt collection. Pitt collection. Provenance: Collecting Antique Bird Decoys and Duck Calls. Provenance: Collecting Antique Bird Decoys and Duck Calls. 426. Mason Factory Detroit Grade Glass Eye blue 428. Mason Factory Detroit Grade Glass Eye mallard winged teal hen decoy in XOC with a short narrow check drake decoy in XOC. Never rigged. Check along the bottom, and a knot on the right side of the back with a few flakes knot on the right side of the body with minor flaking. See of paint off the head. “Glantz” branded on the bottom. See second photo from the bottom page 171 of Luckey and Lewis this exact decoy on the top of page 164 in the Luckey and book for a photo of this exact decoy. 1000-1200 Lewis book. 2500-4500 Pitt collection. Pitt collection. -

MDCA Book List

MDCA Book List Following is a list of the many educational, informative, and beautiful books about decoys and related collectibles. Many are out of print but available through MDCA member dealers and online sources. All books are hard cover and in print unless otherwise noted O/P= out of print from publisher H/C = hard cover S/C = soft cover Aziz Decoys Celebration of Contemporary Decoys, 1994 Wildlife Art – World’s Champion Carvers, 1996 Bacyk Gun Powder Cans and Kegs, 1998 The Encyclopedia of Shotshell Boxes, 2000, H/C, S/C Bakke & Hamm The Last of the Market Hunters, 1996 Barber, Joel Wildfowl Decoys, 1934, 1937, also Deluxe edition of 55 copies, Derrydale Press, 1934. A reprint of the 1934 Deluxe Edit, O/P. I/P is 1954 S/C edition Barrett Lore and Legends of Long Point (Canada) 1977, 1979, 1990, O/P Baron Commercial Fish Decoys, 2001 Be’lisle & St. Onge Decoys from Montreal Region, 1998 Belinko Robert G. Litzenberg, Portrait of a Decoy Carver, 1990, O/P Berkey Chincoteague Carvers and Their Decoys, 1981, O/P Decoy & Wildlife Art Trivia,1989, + S/C , O/P Pioneer Decoy Carvers, Ward Bros., also Deluxe edit, signed by Lem Ward. 1977, O/P Boggess Classic Hunting Collectibles: Identification & Price Guide, 2005. Has posters, calendars, pinbacks, shotshell boxes, catalogs. Bosco Pascagoula Decoys, 2003 Bosworth & Hayes Whistling Wings, Whittled Ducks & Wetlands, 1996, S/C, O/P Bowman Arkansas Duck Hunters Almanac, 1998, S/C, H/C Bourne Auction Co. American Bird Decoys, William Mackey's auction catalogs, 1973, 1974, 5 vols, + S/C, O/P Decoys & Proven Methods for Using Them, 2000 The Rare Decoy Collection of George Ross Starr, Jr., MD, 1986, Auction Catalog, O/P Brisco Waterfowl Decoys & the Men Who Made Them, From SW Ontario, 1986, O/P Bublitz Artists in Wood. -

Day 1, Catalog

Decoys Unlimited, Inc. Theodore S. Harmon Ted and Judy Harmon of DECOYS UNLIMITED, INC. presents OUR ANNUAL SUMMER DECOY & AMERICANA SALE Monday & Tuesday, July 31-August 1, 2006 at the Cape Codder Resort and Hotel Hyannis, MA Telephone: -888-297-2200 www.decoysunlimitedinc.com e-mail: [email protected] SALE: Monday, July 31 • Americana sale starts at 12 PM. The decoy sale follows immediately at the conclusion of the Americana section. Tuesday, August 1 • 11 AM PREVIEW: Sunday, July 30 • 6-8 PM Monday, July 3 • 9 AM - 2 PM Tuesday, August • 8 AM - PM Phone and Absentee Bidding Information See Directions in Back of Catalog For absentee or phone bidding please call Ted Harmon – (508) 362-2766 TERMINOLOGY: XOP - Excellent Original Paint XOC - Excellent Original Condition OP - Original Paint T/U - Touch Up For more information contact: Ted Harmon, P.O. Box 206, West Barnstable, MA 02668 • (508) 362-2766 See Conditions of Sale – Back of Catalog A few words about Dr. Harvey Pitt as remembered by his friend and business partner in P&D Decoys, Mr. Ed Dunham. What to do with the decoy collection? As Pitt lay recovering in a Springfield, IL hospital bed, watching an electric heart monitor confirm he was still alive, the ageing duck hunter realized the rules of material possessions hadn’t changed since 1927. That was the year he was born, which meant he had lived a full life already. Even before that near fatal heart attack in November 2000, Pitt long understood how life and death work. Nobody slips into the afterlife with souvenirs collected on earth. -

Decoys and Decoy Carvers from the Illinois & Michigan Canal National Heritage Corridor

Decoys and Decoy Carvers from the Illinois & Michigan Canal National Heritage Corridor. A paper to accompany a Folk Art Exhibit, January 26 - February 26, 1986. Lewis University Library, Romeoville, Ill., 1986. 174 AN EXHIBIT OF DECOYS FROM THE ILLINOIS AND MICHIGAN CANAL NATIONAL HERITAGE CORRIDOR This is the second exhibit of Folk Art from the Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage Corridor sponsored by Lewis University and the Lewis University Canal Archives, and held in the Lewis University Library. The objective of these exhibits is to explore and record the folk art of the Corridor. This is a neglected area of study, but an important part of our cultural heritage. The University has committed itself to explore and also to pass on to posterity a knowledge of the objects made by skilled but untrained craftsmen, whose artistic vision has been mostly ignored. Decoy making is the most distinctively American of all the folk arts practiced in this country. It is an art not found elsewhere, however, in America examples have been found dating back about 2,000 years. Apparently the Indian reed decoys were not used widely but they were used. The era of wood decoy making began when the West was opened and settlers found what they assumed was an unlimited supply of game birds. This led to that period of animal slaughter by market hunters who supplied thousands of birds to the meat markets of our cities. This era fortunately ended at the turn of the century when prohibitive national legislation was enacted. Some of the old professional hunters, who had made decoys as needed in their hunting, now supplemented their income by making decoys.1 The wooden decoy, either handmade or machine made, flourished from the late 19th century until after World War II. -

Over One Million Hits Monthly Help Recycle, Buy Antiques!

Online! Always On Time! Over One Million Hits Monthly www.auctionactionnews.com Help Recycle, Buy Antiques! July 24, 2013 Vol. 19 No. 01 News Periodical Mailed on July 18 June 9th Show at LaPorte Hosts Many Veteran Dealers Article & photos by Jack Kelly For many antique dealers setting up at the June 9 show at the LaPorte County Fairgrounds in LaPorte, Indiana, it is a return trip that they started 16 years ago – and continues to 2013. Many shoppers over the years have taken home finely refinished furniture from 16-year veteran dealers Marvin and Connie Novak of “I love jewelry, it’s a work of art” said Jim nearby Michigan City, Indiana. Sigler of St. Joseph, Mich., pointing to a pair At the June event the couple showed off more 14-18k bracelets, circa 1883, priced at $7,000. high quality items including a 4-foot-long 54- (269) 429-4996. inch-tall double-door birch bookcase priced at $395. Shoppers also checked out a 62-inch-long 67-inch-tall pine kitchen cupboard tagged at $525. Shoppers stopped to look, Continued A pair of tear-drop-back and sit on, a 62” long pine on pages design 1960s chairs could grace You could gamble at home for boot box, with hinged top, priced at 15 & 16 your home for $200 shown by $900 with a Mills slot machine $325 by Marvin and Connie Novak of Thaddeus Cutler of LaPorte. from Tom and Carol Miller of Michigan City, Ind. (219) 879-6390. (219) 326-8626. Homer Glenn, Ill. (708) 301-5759.