2/1/2018 a Brief History of Gold Mining in the Black Hills

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bhss-Ra-Gelb-Shorthrn-Web

10 • BHSS Livestock & Event Guide A Publication of The Cattle Business Weekly 12 • BHSS Livestock & Event Guide A Publication of The Cattle Business Weekly FRIDAY, JANUARY 17 TUESDAY, JANUARY 28 9am Thar’s Team Sorting - Kjerstad Event Center, Fairgrounds 8am Winter Classic AQHA Horse Show, Halter, Cutting, Roping - Kjerstad Event Center, Fairgrounds SATURDAY, JANUARY 18 8am Best of the West Roping Futurity, Calf Roping and 9am Thar’s Team Sorting - Kjerstad Event Center, Fairgrounds Team Roping classes (to run concurrent with AQHA Classes) - Kjerstad Event Center, Fairgrounds SUNDAY, JANUARY 19 WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 29 9am Thar’s Team Sorting- Kjerstad Event Center, Fairgrounds 8am Winter Classic AQHA Horse Show, Reining & Working Cow Horse - Kjerstad Event Center, Fairgrounds MONDAY, JANUARY 20 8am Winter Spectacular NRCHA Show (run concurrently 8am Equi Brand/Truck Defender Black Hills Stock Show® with the AQHA Working Cow Horse Classes) AQHA Versatility Ranch Horse Competition - Kjerstad Event Center, Fairgrounds - Kjerstad Event Center, Fairgrounds THURSDAY, JANUARY 30 TUESDAY, JANUARY 21 8am Winter Classic AQHA Horse Show, 8am Equi Brand/Truck Defender Black Hills Stock Show® Halter & Roping Classes AQHA Versatility Ranch Horse Competition - Kjerstad Event Center, Fairgrounds - Kjerstad Event Center, Fairgrounds 11am-5pm: Hutchison Western Stallion Row Move-In - Kjerstad Event Center, Fairgrounds WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 22 11-5pm Truck Defender Horse Sale Check-In 9am South Dakota Cutting Horse Association Show - Kjerstad Event Center Warm-Up, -

According to Wikipedia 2011 with Some Addictions

American MilitMilitaryary Historians AAA-A---FFFF According to Wikipedia 2011 with some addictions Society for Military History From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Society for Military History is an United States -based international organization of scholars who research, write and teach military history of all time periods and places. It includes Naval history , air power history and studies of technology, ideas, and homefronts. It publishes the quarterly refereed journal titled The Journal of Military History . An annual meeting is held every year. Recent meetings have been held in Frederick, Maryland, from April 19-22, 2007; Ogden, Utah, from April 17- 19, 2008; Murfreesboro, Tennessee 2-5 April 2009 and Lexington, Virginia 20-23 May 2010. The society was established in 1933 as the American Military History Foundation, renamed in 1939 the American Military Institute, and renamed again in 1990 as the Society for Military History. It has over 2,300 members including many prominent scholars, soldiers, and citizens interested in military history. [citation needed ] Membership is open to anyone and includes a subscription to the journal. Officers Officers (2009-2010) are: • President Dr. Brian M. Linn • Vice President Dr. Joseph T. Glatthaar • Executive Director Dr. Robert H. Berlin • Treasurer Dr. Graham A. Cosmas • Journal Editor Dr. Bruce Vandervort • Journal Managing Editors James R. Arnold and Roberta Wiener • Recording Secretary & Photographer Thomas Morgan • Webmaster & Newsletter Editor Dr. Kurt Hackemer • Archivist Paul A. -

Charles Collins: the SIOUX City Promotion of the Black Hills

Copyright © 1971 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. Charles Collins: The SIOUX City Promotion of the Black Hills JANE CONARD The Black Hills mining frontier. located in southwestern South Dakota, was one of the last regions to experience the turbulence of a gold rush. Rapid development and exploitation of mineral wealth was typical of the gold discoveries in the mountainous West during the Civil War years and the following decade. Although rumors of gold in the Black Hills had persisted throughout these years, the area lay within the Great Sioux Reservation and few white men had had the opportunity of exploring the region to verity the rumors. By the early 1870s public opinion in the Northwest-as Iowa. Nebraska. Minnesota. and Dakota Territory was called-ran strongly in favor of some action by the federal government to open the Black Hills to settlement. The spirit of 'forty-nine lingered on and old miners, ever dreaming of bonanza strikes, sought new gold fields. One step removed from the real and the imaginery gold fields were the merchants and the newspapermen who hoped to outfit the miners, develop new town sites, supply the needs of new communities, and influence the course of men and events. Charles Collins, a newspaperman and promoter from Sioux City, Iowa, spearheaded a campaign to open the Black Hills gold fields to whites. A dynamic Irishman, he sought to put Sioux City on the map as the gateway to the mines, to bring prosperity to the Northwest, and to acquire fame and wealth for himself. -

Lakota Black Hills Treaty Rights

LAKOTA BLACK HILLS TREATY RIGHTS http://www.tribalwisdom.org/treaties.html 1787 - Northwest Ordinance of 1787 – Stated that “The utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their land and property shall never be taken from them without their consent…” 1825 - Removal Act – Created “Permanent Indian Country” in what was considered the “Great American Desert” – Areas west of the western borders of Louisiana, Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa and Minnesota – The year of “Trail of Tears” for Cherokee, Creek & Chickasaw as they are relocated to Oklahoma 1830 - Supreme Court Case (Worcester vs. Georgia) Determined that Indian Nations are “Distinct, independent political communities.” 1842 – First Wagon Trains cross Indian Country on the “Oregon Trail” 1849 – Gold discovered in California – 90,000 settlers moved west through Indian Country and split the Buffalo herd in half. 1851 – First Fort Laramie Treaty - Defined Tribal Areas, committed to a “lasting peace between all nations”, gave US Right to construct roads and military posts, agreed to compensate the tribes $50,000 per year for 50 years, indicated the Black Hills as Lakota land. Annuity could be in the form of farming supplies and cattle, to “save, if possible, some portion of these ill-fated tribes” according to BIA Supt. Mitchell. The US Senate reduced the annuity to 10 years without the Lakota’s knowledge 1857 – Grand Gathering of the Lakota – Held at the base of Bear Butte in the Black Hills. 7,500 Lakota gathered, including Red Cloud, Crazy Horse, and Sitting Bull who pledged to not allow further encroachment by whites. 1858 – Yankton Tribe sold 15 million acres to US, angering the other tribes, who questioned the Yankton’s authority to sell land without full Lakota consent. -

The Black Hills and Badlands of South Dakota

PRESENTS THE BLACK HILLS AND BADLANDS OF SOUTH DAKOTA FEATURING RAPID CITY, MOUNT RUSHMORE, CRAZY HORSE, FORT HAYS, AND DEADWOOD SEPTEMBER 20-26, 2021 AIR & LAND FROM $2,974 7 DAYS, 6 NIGHTS INCLUDING HOTELS, MEALS, DAY TRIPS, AND AIRFARE FROMEarl yINDIANAPOLIS,-Bird IN Special! $3,074, $2,974 if reserved by April 2, 2021. Hurry, at this price the trip will sell out quickly. Excitement and adventure, history and patriotic vibes, monumental sculptures and remnants of the Gold Rush – all of this and so much more awaits you on this thrilling South Dakota travel experience. Delve into Rapid City where you can take in local arts and culture, check out the amazing life-sized bronze statues of past presidents on the downtown’s street corners, explore the great outdoors on a hiking adventure, and indulge in a unique dining scene. Experience the iconic Mount Rushmore presidential sculptures that measure 60 feet in height each and see the world’s largest mountain carving – Crazy Horse Memorial. Join in an exhilarating Buffalo Jeep Safari in Custer State Park. Drive through Badlands National Park, quench your thirst with the famous “free ice water” at the Wall Drug Store, and visit Fort Hayes where Dances With Wolves was filmed. Tour Riddle’s Black Hills Gold and Diamond Factory and motor along the picturesque Needles Highway. Embark on rail journey through history and the great outdoors riding onboard an authentic 1880 narrow-gauge train dating back to the Black Hills Gold Rush era. Truly distinctive experiences and memories for a lifetime are yours to cherish and share from this inspired Black Hills and Badlands vacation. -

Kaitlyn Weldon HIST 4903 Dr. Logan 7 December 2017 The

Kaitlyn Weldon HIST 4903 Dr. Logan 7 December 2017 The Black Hills in Color “Here’s to the hills of yesterday, Here’s to the men they knew, Hunters, Miners, and Cattlemen And Braves of the wily Sioux. Men who rode the lonely trails And camped by the gold-washed streams, Forced the land to accept their brand And suffered the birth of a brave new land… Here’s to their valiant dreams.”1 The Black Hills began as a serene, sacred place to the Native Americans.2 The only color for miles was the dark green trees that gave the Black Hills their name.3 In time, the gold rush would move into the area, introducing many new colors to the region. The colors included red, yellow, black, and white. There were many culturally diverse cities within the Black Hills, and many famous, colorful characters came out of these hills, such as Wild Bill Hickock and Calamity Jane. The Dakota Gold Rush was a tumultuous time in American history, but it was only one of many 19th century, gold rushes that created many tales about the Wild West. The United States (US) government had some interest initially in these rushes because they occurred in territories 1 Martha Groves McKelvie, The Hills of Yesterday, (Philadelphia: Dorrance & Company, Inc., 1960), cover page. 2 McKelvie, The Hills of Yesterday, 18-19. 3 Frederick Whittaker, A Complete Life of General George A. Custer, Volume 2: From Appomattox to the Little Bighorn, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993), 511. Weldon 2 regulated by the federal government, territories such as California, Alaska, Colorado, and Dakota Territory. -

Volume 9 . July 1998 . Number 3

Volume9 . July 1998 . Number3 Mnternational Lost in the Xlondike? North Camllna Gold The organizersof the IV InrematioDal Looking for an arcestor who Jollowed In 1999,Nonh Ca.olinawill observerhe Minirg History Conferenceate putting the gold rushesro lhe Far Nonh? The bicentennialof the first gold ru6hin what the firishing toucheson ihar event to be AlaskaCold RushCenternial Task Force w,s lhen the United States. Cold was held in Guanajuato, Mexico between rerehdy published Hote to Fint your discoveredin Cabalus Counry, ihe filst Novemberl0th atrd 13rh, 1998. The GoM Rush Relalive: Sourcet on the of the Appalachiangold 6elds. Flom Congressis supportedby the Imtiluro Klondike and AlLtl@ GoA Ruthes,1896- September l7 !o 19, 1999, the Nacional de Arthropologia y Histoda J9J4, compiled by R. Bruc€ Parham. Univelsity of North Carolinaat Chado$e (INAH), theAsociacioo de Ingenieros de The reDpage guide is a good reference will serve as host for 'Gold irl Calolina Minas, the Mehlurgistitas y Geologosdo t9ol for aDy researcher; it includcs and America: A Bicenrennial Mexico, A. C., and o&er minillg information on arcbives, intemet Perspective,'a sympGium sponsoredin compsnier and academic institutions. sourc€s,CD-ROMS, newspaper indercs, pan by the Universiry, ReedCold Mine The Congresswill be sinilar to the III etc, For mor€ information contact the StateHistoric Site, surounding couniies, Intemaaionalheld in Golden,Cololado in Stare of Alaska Office of History aDd atrd the Nonh Carolina Division of 1994 wirh professional papers, Archeolos/,360i C Sr., Suite 1278, Archives ard History. Sessioaswill rcceptiorE,and tours, The agendais set Anchorage, AK 99503-5921 or phone examine the history of gold in Nonh and the program drated. -

Jewel Cave National Monument Historic Resource Study

PLACE OF PASSAGES: JEWEL CAVE NATIONAL MONUMENT HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY 2006 by Gail Evans-Hatch and Michael Evans-Hatch Evans-Hatch & Associates Published by Midwestern Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska _________________________________ i _________________________________ ii _________________________________ iii _________________________________ iv Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1: First Residents 7 Introduction Paleo-Indian Archaic Protohistoric Europeans Rock Art Lakota Lakota Spiritual Connection to the Black Hills Chapter 2: Exploration and Gold Discovery 33 Introduction The First Europeans United States Exploration The Lure of Gold Gold Attracts Euro-Americans to Sioux Land Creation of the Great Sioux Reservation Pressure Mounts for Euro-American Entry Economic Depression Heightens Clamor for Gold Custer’s 1874 Expedition Gordon Party & Gold-Seekers Arrive in Black Hills Chapter 3: Euro-Americans Come To Stay: Indians Dispossessed 59 Introduction Prospector Felix Michaud Arrives in the Black Hills Birth of Custer and Other Mining Camps Negotiating a New Treaty with the Sioux Gold Rush Bust Social and Cultural Landscape of Custer City and County Geographic Patterns of Early Mining Settlements Roads into the Black Hills Chapter 4: Establishing Roots: Harvesting Resources 93 Introduction Milling Lumber for Homes, Mines, and Farms Farming Railroads Arrive in the Black Hills Fluctuating Cycles in Agriculture Ranching Rancher Felix Michaud Harvesting Timber Fires in the Forest Landscapes of Diversifying Uses _________________________________ v Chapter 5: Jewel Cave: Discovery and Development 117 Introduction Conservation Policies Reach the Black Hills Jewel Cave Discovered Jewel Cave Development The Legal Environment Developing Jewel Cave to Attract Visitors The Wind Cave Example Michauds’ Continued Struggle Chapter 6: Jewel Cave Under the U.S. -

Dreams and Dust in the Black Hills: Race, Place, and National Identity in America's "Land of Promise" Elaine Marie Nelson

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-19-2011 Dreams and Dust in the Black Hills: Race, Place, and National Identity in America's "Land of Promise" Elaine Marie Nelson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Nelson, Elaine Marie. "Dreams and Dust in the Black Hills: Race, Place, and National Identity in America's "Land of Promise"." (2011). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i ii ©2011, Elaine Marie Nelson iii DEDICATION I wish to dedicate this to my parents—and their parents—for instilling in me a deep affection for family, tradition, history, and home. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I do not remember our first family vacation. My sisters and I were so used to packing up and hitting the road in the family station wagon (later a minivan), that our childhood trips blur together. Oftentimes we visited our paternal grandparents in Sidney, Nebraska, or our maternal grandparents in Lincoln, Nebraska. But on special occasions we would take lengthy road trips that ended with destinations in the Appalachian Mountains, the Gulf of Mexico, Yellowstone National Park, and Myrtle Beach. As an ―East River‖ South Dakotan, driving six hours west to visit the Black Hills was hardly as exciting as going to the beach. -

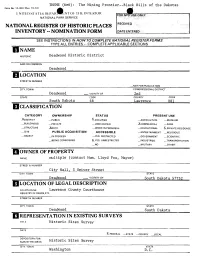

Iowner of Property

THEME (6e6): The Mining Frontier Black Hills of the Dakotas Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) ^^ UNITED STATES DHPARwIiNT OF THH INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Deadwood Historic District AND/OR COMMON Deadwood LOCATION STREET & NUMBER _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Deadwood _ VICINITY OF 2nd STATE CODE COUNTY CODE South Dakota 46 Lawrence 081 Q CLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT _PUBLIC ^-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED -X.COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE _XBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT ._IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED X_YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME multiple (contact Hon. Lloyd Fox, Mayor) STREEF& NUMBER City Hall, 5 Seiver Street CITY, TOWN STATE Deadwood VICINITY OF South Dakota 57732 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, Lawrence County Courthouse REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Deadwood South Dakota I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey DATE ^.FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORYSURVEY RECORDS FOR HistoricTT . Sites-, . Survey„ CITY, TOWN STATF. Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS XXALTERED MOVED DATF _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Deadwood was a boom town created in 1875 during the Black Hills gold rush. The district is situated in the central area of the town of Deadwood and lies in a steep and narrow valley. -

The Good, the Bad & the Ugly

reisreportage reisreportage THE GOOD, THE BAD & THE UGLY Wildwest in South Dakota Het échte Wilde Westen van Amerika ligt in South Dakota. Cowboys, indianen, gokkers en goudzoekers vochten elkaar hier ooit de tent uit. Hoewel het prairiestof al lang en breed is neergedaald, struikel je in het land van bizons en Badlands nog steeds over sporen uit het ruige verleden. Tekst: Ard Krikke Beeld: Chad Choppess & Ard Krikke 88 | SALT lente 2016 SALT lente 2016 | 89 reisreportage reisreportage “ ihaaaa!” Een langgerekte kreet ontsnapt uit mijn de cowboy niets teveel heeft gezegd. En dan is het plots voor- mond. Dik dertienhonderd op hol geslagen bizons bij. Gedwee geven de donkerbruine wildebrassen zich gewon- denderen over de golvende prairieheuvels op me nen. Met speels gemak manen de ruiters de uitgebluste troep af. De chauffeur van de pick-up waarop ik sta geeft richting de corral. “De Roundup verliep vrij soepeltjes”, be- Yvol gas om de opgefokte kolossen, zo groot als een Fiat 500, aamt game warden Ron Tietsoord na afloop. Met zijn pistool, te ontwijken. Zelf moet ik alle zeilen bijzetten om niet van zweep, gespoorde laarzen en grote cowboyhoed oogt hij als de hobbelende laadbak te vallen. Boven het oorverdovende een onvervalste sheriff. ”Door het uitzonderlijk warme weer geroffel van ontelbare hoeven klinken plotsklaps schoten. van de afgelopen weken zijn de dieren een stuk slomer dan Door een wolk van stof en gras zie ik dat de naast de kudde normaal. Ik heb ook wel eens meegemaakt dat een duizend galopperende cowboys niet hun pistolen, maar hun zweep kilo zwaar mannetje een auto omver kegelde. -

SBCC-Report Revised

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. The 730-acre property at Sitting Bull Crystal Caverns (SBCC) is of great significance to the geological history of the Black Hills, as well as the histories of South Dakota tourism and, most importantly, of the Oceti Sakowin (“Great Sioux Nation”). Located about ten miles south of downtown Rapid City on Highway 16, the property sits in the heart of the sacred Black Hills (Paha Sapa), which are the creation place of the Lakota people. The Sitting Bull Cave system—named after the famed Hunkpapa leader, who is said to have camped on the property in the late 1800s—is located in the “Pahasapa limestone,” a ring of sedimentary rock on the inner edges of the “Racetrack” described in Lakota oral traditions. There are three caves in the system. The deepest, “Sitting Bull Cave,” boasts some of the largest pyramid-shaped “dog tooth spar” calcite crystals anywhere in the world. The cave opened to tourists after significant excavation in 1934 and operated almost continuously until 2015. It was among the most successful early tourist attractions in the Black Hills, due to the cave’s stunning beauty and the property’s prime location on the highway that connects Rapid City to Mount Rushmore. 2. The Duhamel Sioux Indian Pageant was created by Oglala Holy Man Nicholas Black Elk and held on the SBCC grounds from 1934 to 1957. Black Elk was a well-known Oglala Lakota whose prolific life extended from his experience at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876 to the publication of Black Elk Speaks in 1932 and beyond.