Freezing Guide for Fresh Vegetables

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhubarb Asheville

RHUBARB TAKE-AWAY MENU SNACKS Asparagus, English Peas 7 Comeback Sauce 5 Blue Cheese, BBQ Salt 7.5 House-Made Saltines, Bread & Butter Pickles 7 Chapata Toast, Red Onion Jam, Strawberry-Green Peppercorn Compote, Crispy Shallots 12 E Y V Benton’s Bacon 6.5 Mimosa Egg, Sauce Gribiche, Ramp Breadcrumbs, Pickled Red Onion 10 LG Feta, Pecans, Shaved Vegetables, Strawberry-Banyuls Vinaigrette 12 Flageolet Beans, Local Mushrooms, Tuscan Kale, Fennel Tops, Breadcrumbs 17 SANDWICHES Seared Double Beef & Bacon Patty, B&B Pickles, French Fries 11.5 - Add House Pimiento Cheese, Ashe County Cheddar or Ashe County Gouda 2 Gouda, Spiced Green Tomatoes, Radicchio, Sweet Potato Brioche, French Fries 11.5 Pepper-Vinegar BBQ Sauce, Chow-Chow, Brioche Bun, French Fries 13.5 ENTREES Dandelion Greens, Fennel Confit, Hoppin’ John, Fennel Pesto, Pickled Fennel 24 Pea and Carrot Potage, Asparagus, Herb Salad 23 20 Spring Risotto, Asparagus, Peas, Ramps, Parsley Root, Sorrel Pistou 23 Farm & Sparrow Grits, Garlic Confit, Hearty Greens, Breadcrumbs 18 Roasted Red Bliss Potatoes, Green Garlic, Spinach, Wild Ramps, GG Parsley Chermoula 23 Roasted Rutabaga, Rapini, House Steak Sauce, Pickled Radish 24 Dessert CHILDREN’s MENU Whipped Cream 6 5 Streusel Topping 6 5 5 NON-ALCOHOLIC (1L) 6 3 2 Beer WINE Jean-Luc Joillot, Crémant De Bourgogne Brut, Burgundy, France NV 20 375ml Clara Vie, Brut, Crémant de Limoux, Languedoc-Roussillon, France NV 22 Miner, Simpson Vineyard, Viognier, Napa Valley, California 2017 16 375ml Mayu, Huanta Vineyard, Pedro Ximenez, Valle De Elqui, -

Rutabagas Michigan-Grown Rutabagas Are Available Late September Through November

Extension Bulletin HNI52 • October 2012 msue.anr.msu.edu/program/info/mi_fresh Using, Storing and Preserving Rutabagas Michigan-grown rutabagas are available late September through November. Written by: Katherine E. Hale MSU Extension educator Recommended • Use rutabagas in soups or stew, or bake, boil or steam and slice or varieties mash as a side dish. Lightly stir- American Purple Top, Thomson fry or eat raw in salads. Rutabaga Laurentian and Joan is traditional in Michigan pasties, along with potatoes, carrots and Interesting facts beef. • Harvest when they reach the size • Rutabaga belongs to the of a softball. You may harvest Cruciferae or mustard family and rutabagas as they reach edible size the genus Brassica, classified as and throughout the season since Brassica napobrassica. they will keep in the ground. • Developed during the Middle Ages, rutabagas are thought to be a cross between Storage and food safety the turnip and the cabbage. • Wash hands before and after handling fresh fruits and • The rutabaga is an excellent source of vitamin C and vegetables. potassium, and a good source for fiber, thiamin, vitamin B6, calcium, magnesium, vitamin A and manganese. • Rutabagas will keep for months in a cool storage place. They store well in plastic bags in a refrigerator or cold cellar. • Similar to the turnip but sweeter, rutabagas are inexpensive and low in calories. • Keep rutabagas away from raw meat and meat juices to prevent cross contamination. Tips for buying, preparing • Before peeling, wash rutabagas using cool or slightly warm and harvesting water and a vegetable brush. • Look for smooth, firm vegetables with a round shape. -

Preventive Controls for Animal Food Safety

Vol. 80 Thursday, No. 180 September 17, 2015 Part III Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration 21 CFR Parts 11, 16, 117, et al. Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Food for Animals; Final Rule VerDate Sep<11>2014 19:06 Sep 16, 2015 Jkt 235001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\17SER3.SGM 17SER3 mstockstill on DSK4VPTVN1PROD with RULES3 56170 Federal Register / Vol. 80, No. 180 / Thursday, September 17, 2015 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND Administration, 7519 Standish Pl., IX. Subpart A: Comments on Qualifications HUMAN SERVICES Rockville, MD 20855, 240–402–6246, of Individuals Who Manufacture, email: [email protected]. Process, Pack, or Hold Animal Food Food and Drug Administration A. Applicability and Qualifications of All SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Individuals Engaged in Manufacturing, Table of Contents Processing, Packing, or Holding Animal 21 CFR Parts 11, 16, 117, 500, 507, and Food (Final § 507.4(a), (b), and (d)) 579 Executive Summary B. Additional Requirements Applicable to Purpose and Coverage of the Rule Supervisory Personnel (Final § 507.4(c)) [Docket No. FDA–2011–N–0922] Summary of the Major Provisions of the Rule X. Subpart A: Comments on Proposed RIN 0910–AG10 Costs and Benefits § 507.5—Exemptions I. Background A. General Comments on the Proposed Current Good Manufacturing Practice, A. FDA Food Safety Modernization Act Exemptions Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based B. Stages in the Rulemaking for the Animal B. Proposed § 507.5(a)—Exemption for Food Preventive Controls Rule Facilities Not Required To Register Preventive Controls for Food for C. -

Rutabaga Volume 1 • Number 12

Rutabaga Volume 1 • Number 12 What’s Inside l What’s So Great about Rutabaga? l Selecting and Storing Rutabaga l Varieties of Rutabaga l Fitting Rutabaga into MyPyramid l Recipe Collection l Grow Your Own Rutabaga l Activity Alley What’s So Great about Rutabaga? ; Rutabagas are an excellent source of vitamin C, and a good source of potassium, fiber and vitamin A. ; Rutabagas are low in calories and are fat free. ; Rutabaga’s sweet, mildly peppery flesh makes great side dishes. ; Rutabagas are tasty in salads, soups, and stews. Rutabagas are inexpensive. Selecting and Storing Rutabaga Rutabagas are available all year. But these root vegetables are Why is Potassium best in the fall. Rutabagas are often trimmed of taproots and tops. Important? When found in the grocery store, they are coated with clear wax to prevent moisture loss. Eating a diet rich in potassium and lower in sodium is Look for good for your health. Potassium is an electrolyte that Firm, smooth vegetables with a round, oval shape. Rutabagas helps keep body functions normal. It may also help pro- should feel heavy for their size. tect against high blood pressure. Potassium is found in fruits and vegetables. Avoid Avoid rutabagas with punctures, deep cuts, cracks, or decay. Root vegetables like rutabagas are good sources of potassium. Most adults get adequate amounts of potas- Storage sium in their diet. To be sure you are eating enough, go Rutabagas keep well. Refrigerate in a to www.MyPyramid.gov to see how many fruits and plastic bag for two weeks or more. -

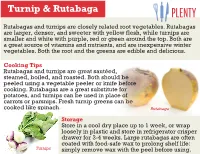

Turnip & Rutabaga

Turnip & Rutabaga Rutabagas and turnips are closely related root vegetables. Rutabagas are larger, denser, and sweeter with yellow flesh, while turnips are smaller and white with purple, red or green around the top. Both are a great source of vitamins and nutrients, and are inexpensive winter vegetables. Both the root and the greens are edible and delicious. Cooking Tips Rutabagas and turnips are great sautéed, steamed, boiled, and roasted. Both should be peeled using a vegetable peeler or knife before cooking. Rutabagas are a great substitute for potatoes, and turnips can be used in place of carrots or parsnips. Fresh turnip greens can be cooked like spinach. Rutabaga Storage Store in a cool dry place up to 1 week, or wrap loosely in plastic and store in refrigerator crisper drawer for 3-4 weeks. Large rutabagas are often coated with food-safe wax to prolong shelf life: Turnips simply remove wax with the peel before using. Quick Shepherd’s Pie Ingredients: • 1 lb rutabaga or turnip (or both) • ¼ cup low-fat milk • 2 tbsp butter • ½ tsp salt • ½ tsp pepper • 1 tbsp oil (olive or vegetable) • 1 lb ground lamb or beef • 1 medium onion, finely chopped • 3-4 carrots, chopped (about 2 cups) • 3 tbsp oregano • 3 tbsp flour • 14 oz chicken broth (reduced sodium is best) • 1 cup corn (fresh, canned, or frozen) Directions: 1. Chop the rutabaga/turnip into one inch cubes. 2. Steam or boil for 8-10 minutes, or until tender. 3. Mash with butter, milk, and salt and pepper. Cover and set aside. 4. Meanwhile, heat oil in a skillet over medium-high heat. -

Improving the Root Vegetables

IMPROVING THE ROOT VEGETABLES C. F. PooLE, Cytologist, Division of Fruit and Vegetable Crops and Diseases, Bureau of Plant industry LJlD the ancient civilizations arise in the regions where our common cultivated food plants originated and were naturally abundant? Or did man take food plants with him, so that the early centers of civili- zation only seem to be the centers of origin of the plants? This must remain an interesting subject of speculation, but few students doubt that civilization was dependent on the natural locations of the plants. At any rate, the regions that are now believed to be the natural centers of origin of the root vegetables (40, 4^)/ which were used as food long before recorded history, include practically all of the centers of the oldest civilizations. The present belief is that in the Old World there were six of these, with five of which we are here concerned, and in the New World two major and two minor centers, all of which produced valuable root vegetables: (1) Central and western China—radish, turnip, taro (dasheen). (2) India (except northwestern India)—taro. (3) Middle Asia (Punjab and Kashmir)—turnip, rutabaga, radish, carrot. (4) Near Asia—turnip (secondary center), beet, carrot. (5) The Mediterranean—turnip, rutabaga, beet, parsnip, salsify. (6) Ethiopia—no root vegetables. (7) Mexico—swectpotato. (8) South America (major)—taro, potato. (8a) Chile—potato. (8b) Brazil-Paraguay—cassava. The theory is that the place where a plant exhibits the greatest diversity of subspecies and varieties in its natural state must have been a center of origin of that plant. -

Download a PDF of Freezing Summer's Bounty of Vegetables

NUTRITION Freezing Summer’s Bounty of Vegetables ► By following a few simple steps, you can successfully freeze and store almost any vegetable for up to a year. When properly selected, prepared, frozen, and stored, vegetables hold their fresh qualities—the flavor, color, texture, and nutritive value does not change. Using a few important techniques to freeze vegetables can help to ensure a quality product. Select Suitable Vegetables Select the fresh vegetables that your family enjoys eating, focusing on those that are especially suitable for freezing (table 1). Do not put too much importance on varieties; other factors are equally important. Pick Vegetables at the Right Time Vegetables that are tender and just mature are best. better if picked in the early morning when the dew is just The fresher the vegetable when put in the freezer, the off the vines. The shorter the time between harvesting more satisfactory the product. Vegetables are generally and freezing, the better the resulting product. Table 1. Vegetable Varieties for Freezing Vegetable Time in Vigorously Boiling Water Beans (bush, snap) Contender, Black Valentine, Harvester, Top Crop Beans (pole, snap) Kentucky Wonder 191, Blue Lake 231, McCaslan, Blue Lake (colored) Beans (pole, lima) Carolina Sieva, Florida Speckled Beets Detroit Dark Red Carrots Red Cored Chantenay, Danvers 126 Cauliflower Snowball Corn Silver Queen (white) Eggplant Black Beauty, Florida Highbursh Mustard Southern Giant Curled, Florida Broadleaf Okra Clemson Spineless, Emerald Peas (garden) Little Marvel Peas (field) White Acre, Pinkeye Purple Hull, Mississippi Silver Pepper (sweet) Keystone Resistant, Yolo Wonder L Spinach Bloomsdale Savoy Squash (summer) Yellow Crookneck, Dixie, Early Prolific Turnip greens Shogoin (mild), Purple Top White Globe HE-0016-A Prepare Vegetables for Freezing Prepare vegetables for freezing in much the same manner as for cooking. -

Recipe List by Page Number

1 Recipes by Page Number Arugula and Herb Pesto, 3 Lemon-Pepper Arugula Pizza with White Bean Basil Sauce, 4 Shangri-La Soup, 5 Summer Arugula Salad with Lemon Tahini Dressing, 6 Bok Choy Ginger Dizzle, 7 Sesame Bok Choy Shiitake Stir Fry, 7 Bok Choy, Green Garlic and Greens with Sweet Ginger Sauce, 8 Yam Boats with Chickpeas, Bok Choy and Cashew Dill Sauce, 9 Baked Broccoli Burgers, 10 Creamy Dreamy Broccoli Soup, 11 Fennel with Broccoli, Zucchini and Peppers, 12 Romanesco Broccoli Sauce, 13 Stir-Fry Toppings, 14 Thai-Inspired Broccoli Slaw, 15 Zesty Broccoli Rabe with Chickpeas and Pasta, 16 Cream of Brussels Sprouts Soup with Vegan Cream Sauce, 17 Brussels Sprouts — The Vegetable We Love to Say We Hate, 18 Roasted Turmeric Brussels Sprouts with Hemp Seeds on Arugula, 19 Braised Green Cabbage, 20 Cabbage and Red Apple Slaw, 21 Cabbage Lime Salad with Dijon-Lime Dressing, 22 Really Reubenesque Revisited Pizza, 23 Simple Sauerkraut, 26 Chipotle Cauliflower Mashers, 27 Raw Cauliflower Tabbouleh, 28 Roasted Cauliflower and Chickpea Curry, 29 Roasted Cauliflower with Arugula Pesto, 31 Collard Green and Quinoa Taco or Burrito Filling, 32 Collard Greens Wrapped Rolls with Spiced Quinoa Filling, 33 Mediterranean Greens, 34 Smoky Collard Greens, 35 Horseradish and Cannellini Bean Dip, 36 Kale-Apple Slaw with Goji Berry Dressing, 37 Hail to the Kale Salad, 38 Kid’s Kale, 39 The Veggie Queen’s Husband’s Daily Green Smoothie, 40 The Veggie Queen’s Raw Kale Salad, 41 Crunchy Kohlrabi Quinoa Salad, 42 Balsamic Glazed Herb Roasted Roots with Kohlrabi, -

Black Leg, Light Leaf Spot and White Leaf Spot in Crucifers

A CLINIC CLOSE-UP Black Leg, Light Leaf Spot, and White Leaf Spot in Western Oregon Oregon State University Extension Service January 2016 A number of foliar fungal diseases can affect crucifer crops. Three fungal pathogens have emerged recently in western Oregon where epidemics of black leg, light leaf spot, and white leaf spot have been occurring since 2014. Black leg has been detected sporadically in Oregon since the 1970’s but historically black leg has caused significant problems wherever crucifers were grown. Crucifer seed rules have been in place within Oregon, Washington, and other markets to protect crucifer crops from black leg. Light leaf spot is new to North America, but has been reported in other regions of the world where it is known to cause significant seed yield losses of winter oilseed rape. Light leaf spot and black leg can both result in reduced yields or quality, depending on disease incidence and severity in vegetable and seed fields. White leaf spot has been previously reported in the US, but management has not normally been needed except in the southeastern US. White leaf spot may be less of an economic threat to crucifer production in the Pacific Northwest, compared to the risks from black leg and light leaf spot. The complete host range for these three diseases is not known at this time but it is likely that all Brassica and Raphanus crops grown in the Pacific Northwest are susceptible to some degree. These three diseases may be found on volunteer Brassica, Raphanus, and Sinapis species as well as crucifer weed species including little bittercress (Cardamine oligosperma), western yellowcress (Rorippa curvisiliqua), field pennycress (Thlaspi arvense), wild radish (Raphanus sativus), shepherd’s purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris), hedge mustard (Sisymbrium officinale), and field mustard or birdsrape mustard (Brassica rapa var. -

MISE EN PLACE 09 PH Labensky 861442 5/20/02 12:53 PM Page 164

09_PH_Labensky_861442 5/20/02 12:53 PM Page 162 WHEN YOU BECOME A GOOD COOK, YOU BECOME A GOOD CRAFTSMAN, FIRST. YOU REPEAT AND REPEAT AND REPEAT UNTIL YOUR HANDS KNOW HOW TO MOVE WITHOUT THINKING ABOUT IT. —Jacques Pepin, French chef and teacher (1935–) 09_PH_Labensky_861442 5/20/02 12:53 PM Page 163 9 MISE EN PLACE 09_PH_Labensky_861442 5/20/02 12:53 PM Page 164 AFTER STUDYING THIS CHAPTER, YOU WILL BE The French term mise en place (meez ahn plahs) literally means “to ABLE TO: put in place” or “everything in its place.” But in the culinary context, it means much more. Escoffier defined the phrase as “those elementary ᭤ organize and plan your work more efficiently preparations that are constantly resorted to during the various steps of ᭤ understand basic flavoring most culinary preparations.” He meant, essentially, gathering and prep- techniques ping the ingredients to be cooked as well as assembling the tools and ᭤ prepare items needed prior to equipment necessary to cook them. actual cooking In this chapter, we discuss many of the basics that must be in place ᭤ set up and use the standard breading procedure before cooking begins: for example, creating bouquets garni, clarifying butter, making bread crumbs, toasting nuts and battering foods. Chop- ping, dicing, cutting and slicing—important techniques used to prepare foods as well—are discussed in Chapter 6, Knife Skills, while specific preparations, such as roasting peppers and trimming pineapples, are discussed elsewhere. The concept of mise en place is simple: A chef should have at hand every- thing he or she needs to prepare and serve food in an organized and efficient manner. -

Brassica Napus Var

Genome Genetics and molecular mapping of resistance to Plasmodiophora brassicae pathotypes 2, 3, 5, 6 and 8 in rutabaga (Brassica napus var. napobrassica) Journal: Genome Manuscript ID gen-2016-0034.R1 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the Author: 04-May-2016 Complete List of Authors: Hasan, Muhammad Jakir; University of Alberta, Department of Agricultural, Food and NutritionalDraft Science Rahman, M. H.; Univ Alberta, Department of Agricultural, Food and Nutritional Science Keyword: Brassica napus, Rutabaga, Canola, Clubroot resistance, Mapping https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/genome-pubs Page 1 of 36 Genome Genetics and molecular mapping of resistance to Plasmodiophora brassicae pathotypes 2, 3, 5, 6 and 8 in rutabaga ( Brassica napus var. napobrassica ) Muhammad Jakir Hasan and Habibur Rahman M. J. Hasan, and H. Rahman. Department of Agricultural, Food and Nutritional Science, University of Alberta, 4-10 Agriculture/Forestry Centre, Edmonton, AB, T6G 2P5, Canada Corresponding author : Habibur Rahman (e-mail: [email protected]) Draft 1 https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/genome-pubs Genome Page 2 of 36 Abstract: Clubroot disease, caused by Plasmodiophora brassicae , is a threat to the production of Brassica crops including oilseed B. napus . In Canada, several pathotypes of this pathogen, such as pathotype 2, 3, 5, 6 and 8, were identified, and resistance to these pathotypes was found in a rutabaga ( B. napus var. napobrassica ) genotype. In this paper, we report the genetic basis and molecular mapping of this resistance by use of F 2, backcross (BC1) and doubled haploid (DH) populations generated from crossing of this rutabaga line to a susceptible spring B. napus canola line. -

Drying Foods Guide E-322 Revised by Nancy C

Drying Foods Guide E-322 Revised by Nancy C. Flores and Cindy Schlenker Davies1 Objectives • To provide general directions for pre- paring foods for drying. • To provide general directions for dry- ing foods and making safe jerky. • To provide specific directions for the preparation and drying of fruits and vegetables. Introduction Drying or dehydration—the oldest meth- od of food preservation—is particularly successful in the hot, dry climates found in much of New Mexico. Quite simply, drying removes moisture from food, and moisture is necessary for the bacterial growth that eventually causes spoilage. (© Sebastian Czapnik | Dreamstime.com) Successful dehydration depends upon a slow, steady heat supply to ensure that food is dried from the inside to the outside. Most fruits Blanching and vegetables must be prepared by blanching—and in Blanching stops detrimental enzyme action within the some cases by adding preservatives—to enhance color plant tissue and also removes any remaining surface bac- and microbial shelf-life of the dried food. However some teria and debris. Blanching breaks down plant tissue so fruits, such as berries, are not blanched before drying. it dries faster and rehydrates more quickly after drying. Drying is an inexact science. Size of food pieces, relative Although steam blanching and water blanching are both moisture content of the food, and the method selected all discussed in this guide, water blanching is preferred to affect the time required to dehydrate a food adequately. steam blanching. Fully immersing the food in boiling water will ensure a complete heat treatment. Blanch for the required time (Tables 1 and 2), then chill food General Directions for Preparing quickly in an ice bath to stop any further cooking.