Women's Rights Violations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mon-Khmer Studies Volume 41

Mon-Khmer Studies VOLUME 42 The journal of Austroasiatic languages and cultures Established 1964 Copyright for these papers vested in the authors Released under Creative Commons Attribution License Volume 42 Editors: Paul Sidwell Brian Migliazza ISSN: 0147-5207 Website: http://mksjournal.org Published in 2013 by: Mahidol University (Thailand) SIL International (USA) Contents Papers (Peer reviewed) K. S. NAGARAJA, Paul SIDWELL, Simon GREENHILL A Lexicostatistical Study of the Khasian Languages: Khasi, Pnar, Lyngngam, and War 1-11 Michelle MILLER A Description of Kmhmu’ Lao Script-Based Orthography 12-25 Elizabeth HALL A phonological description of Muak Sa-aak 26-39 YANIN Sawanakunanon Segment timing in certain Austroasiatic languages: implications for typological classification 40-53 Narinthorn Sombatnan BEHR A comparison between the vowel systems and the acoustic characteristics of vowels in Thai Mon and BurmeseMon: a tendency towards different language types 54-80 P. K. CHOUDHARY Tense, Aspect and Modals in Ho 81-88 NGUYỄN Anh-Thư T. and John C. L. INGRAM Perception of prominence patterns in Vietnamese disyllabic words 89-101 Peter NORQUEST A revised inventory of Proto Austronesian consonants: Kra-Dai and Austroasiatic Evidence 102-126 Charles Thomas TEBOW II and Sigrid LEW A phonological description of Western Bru, Sakon Nakhorn variety, Thailand 127-139 Notes, Reviews, Data-Papers Jonathan SCHMUTZ The Ta’oi Language and People i-xiii Darren C. GORDON A selective Palaungic linguistic bibliography xiv-xxxiii Nathaniel CHEESEMAN, Jennifer -

GLOBAL SUSTAINABLE PALM OIL MILESTONES January 2017 – December 2017 Data, 2018 Grievances & Actions

GLOBAL SUSTAINABLE PALM OIL MILESTONES January 2017 – December 2017 Data, 2018 Grievances & Actions Table of Contents Kellogg’s Global Sustainable Palm Oil Approach Sustainable Palm Oil Approach………….……….1 Sourcing and Engagement……………….…………2 This report builds on the first half 2017 report issued in June 2018, and captures CPO and PKO Percent Certified……………..……2 2018 grievances and actions through September. Traceability………………………………………………...2 Supply Chain Highlights………………………………3 Palm oil continues to be an ingredient of particular focus for Kellogg Company in our 2017 Metrics Highlights…………………….……....3 responsible sourcing efforts. Although Kellogg uses a very small amount of palm oil Top 5 Supplier Overview…………………….……...4 globally, we have been working since 2009 to improve the sustainability of our palm Supply Chain Details………………………….……....5 oil supply chains and we continue to support responsible sourcing of palm oil Policy Compliance and Grievances…..……..… 5 through our Global 2020 Sustainability Commitments. All of the palm oil we use Supplier Engagement on Grievances………....6 globally is sourced through a combination of the Roundtable of Sustainable Palm Oil Investigative Process……………………….……..….6 (RSPO) Certified Segregated supply chain, RSPO Mass Balance mixed-source supply Updated Grievance Tracker Detail…..…….……7 chain and the purchase of RSPO Credits. Ongoing Grievances……………..…………...…..…10 Kellogg Action…………….……………………………..11 Throughout 2017 and 2018, Kellogg has continued to engage with suppliers, stakeholders, peers, and industry groups to support efforts to reform and improve identified issues within the palm oil industry. As we move forward, Kellogg is committed to the evolution and continued improvement of policies and methods of execution of our palm oil strategy. Kellogg supports increasing transparency of palm oil supply chains at all levels to better enable targeted action and measurable change. -

AAK AB Communications of Progress 2017

RSPO Annual AAK AB Communications of Progress 2017 Particulars About Your Organisation 1.1 Name of your organization AAK AB 1.2 What is/are the primary activity(ies) or product(s) of your organization? Oil Palm Growers Palm Oil Processors and/or Traders Consumer Goods Manufacturers Retailers Banks and Investors Social or Development Organisations (Non Governmental Organisations) Environmental or Nature Conservation Organisations (Non Governmental Organisations) Affiliate Members Supply Chain Associate 1.3 Membership number 2-0001-04-000-00 1.4 Membership category Ordinary 1.5 Membership sector Palm Oil Processors and/or Traders Particulars Form RSPO Annual AAK AB Communications of Progress 2017 Palm Oil Processors and Traders Operational Profile 1.1 Please state your main activity(ies) within the supply chain Refiner of CPO and CPKO Post-refinery processor Trader with physical posession Trader without physical posession Kernel Crusher Food and non-food ingredients producer Power, energy and bio-fuel Animal feed producer Producer of oleochemicals Distributor and wholesaler Other Palm Oil and Certified Sustainable Palm Oil Use 2.1 Please include details of all operations using palm oil majority owned and/or managed by the member and/or related entities 2.1.1 In which markets do you sell goods containing palm oil and oil palm products? ● Applies Globally 2.2 Volumes of palm oil and oil palm products 2.2.1 Total volume of crude and refined Palm Oil handled/traded/processed in the year 1,015,000.00 Tonnes 2.2.2 Total volume of crude and refined -

AAK Annual Report 2017

AAK Annual Report 2017 The Co-Development Company AAK in 60 seconds At AAK, we have developed value-adding vegetable oil With our headquarters in Malmö, Sweden, 20 production solutions for more than 140 years. Today, we work within facilities and customization plants, and sales offices in more industries such as chocolate and confectionery, bakery, dairy, than 25 countries, our more than 3,300 employees are infant nutrition, medical nutrition, senior nutrition, foodservice, dedicated to providing innovative value-adding solutions to and cosmetics. our customers. To make sure we always get the right result we use many So, no matter where you are in the world, we are ready to different raw materials and processing methods. We believe help you achieve long-lasting results. in a collaborative approach where we bring together our customers’ skills and know-how with our own capabilities and mindset. We find this to be the best way to achieve long- We are AAK – The Co-Development Company. lasting results. Three business areas Food Ingredients Our largest business area primarily offers solutions to the bakery, dairy, foodservice and special nutrition industries. The latter includes solutions within infant, senior and medical nutrition. Chocolate & Confectionery Fats Our second largest business area offers functional cocoa butter alternatives for chocolate, compounds for coating and molding, and speciality fats for confectionery fillings. Technical Products & Feed Our Technical Products & Feed business area offers fatty acids and glycerine for -

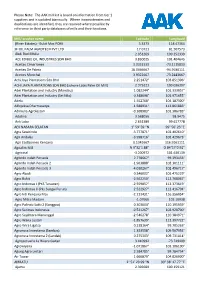

The AAK Mill List Is Based on Information from Tier 1 Suppliers and Is Updated Biannually

Please Note: The AAK mill list is based on information from tier 1 suppliers and is updated biannually. Where inconsistencies and duplications are identified, they are resolved where possible by reference to third party databases of mills and their locations. Mill/ crusher name Latitude Longitude (River Estates) - Bukit Mas POM 5.3373 118.47364 3F OIL PALM AGROTECH PVT LTD 17.0721 81.507573 Abdi Budi Mulia 2.051269 100.252339 ACE EDIBLE OIL INDUSTRIES SDN BHD 3.830025 101.404645 Aceites Cimarrones 3.0352333 -73.1115833 Aceites De Palma 18.0466667 -94.9186111 Aceites Morichal 3.9322667 -73.2443667 Achi Jaya Plantations Sdn Bhd 2.251472° 103.051306° ACHI JAYA PLANTATIONS SDN BHD (Johore Labis Palm Oil Mill) 2.375221 103.036397 Adei Plantation and Industry (Mandau) 1.082244° 101.333057° Adei Plantation and Industry (Sei Nilo) 0.348098° 101.971655° Adela 1.552768° 104.187300° Adhyaksa Dharmasatya -1.588931° 112.861883° Adimulia Agrolestari -0.108983° 101.386783° Adolina 3.568056 98.9475 Aek Loba 2.651389 99.617778 AEK NABARA SELATAN 1° 59' 59 "N 99° 56' 23 "E Agra Sawitindo -3.777871° 102.402610° Agri Andalas -3.998716° 102.429673° Agri Eastborneo Kencana 0.1341667 116.9161111 Agrialim Mill N 9°32´1.88" O 84°17´0.92" Agricinal -3.200972 101.630139 Agrindo Indah Persada 2.778667° 99.393433° Agrindo Indah Persada 2 -1.963888° 102.301111° Agrindo Indah Persada 3 -4.010267° 102.496717° Agro Abadi 0.346002° 101.475229° Agro Bukit -2.562250° 112.768067° Agro Indomas I (PKS Terawan) -2.559857° 112.373619° Agro Indomas II (Pks Sungai Purun) -2.522927° -

Palm Oil: Report 30

Palm Oil Report Report 30 August 2020 1 Table of Contents Cases identified using Sentinel imagery Malaysian Companies New Cases LKPP Corporation Sdn Bhd: PKPP Plantation Sdn Bhd 3 Instant Star Holdings Sdn Bhd: Aspirasi Kristal (M) Sdn Bhd (area A) 5 Instant Star Holdings Sdn Bhd: Aspirasi Kristal (M) Sdn Bhd (area B) 9 Amanah Saham Pahang: Mentiga Corporation Bhd (area A) 11 Amanah Saham Pahang: Mentiga Corporation Bhd (area B) 13 Amanah Saham Pahang: Amanah Saham Pahang (ASPA) - Berabong Estate 15 Yayasan Pahang: YP Plantation Sdn Bhd 17 Supply Chain Information: Amanah Saham Pahang and YP Plantation 19 Unresolved Cases Samling: Samling LPF 0008 Merudi and Batu Belah 22 Supply chain information: Supply chain information included in Rapid Response reports is based on the latest public versions of mill disclosures, recent export data and grievance logs. Mighty Earth encourages companies to send updated versions of mill disclosures as soon as they become available and to share any decision to suspend relations with a given group/company listed in those mill disclosures; please send to [email protected]. Mighty Earth is now including biofuel companies in the supply chain tables of Rapid Response reports, as these companies have both direct and indirect trading relationships with groups highlighted in these reports and should be filing grievances on these cases. These biofuel companies are listed in the “Traders and Biofuel Companies” tables. 2 New Case Group: LKPP Corporation Sdn Bhd PKPP Plantation Sdn Bhd Concession location: (3.860507, 103.085155) Deforestation and/or peat development Peat Peat forest Clearance Deforestation Report development development prep/Stacking Time period (ha) (ha) (ha) lines (ha) February 11, 2019 – Report 30 101 - - - May 20, 2020 Satellite imagery (see below) shows that between February 11, 2019 and May 20, 2020 a total of 101 hectares of forest was cleared in the PKPP Plantation Sdn Bhd concession. -

Responsible Growth

Responsible growth AAK Sustainability Report 2014/2015 The first choice for valueadding vegetable oil solutions Responsible growth Scope At AAK, sustainable development is fundamental to our This report covers AAK’s entire organization, including business. Hand in hand with financial growth, social and production plants, administrative offices, sales offices and environmental responsibility is key to our continued devel sourcing operations. The environmental data is restricted opment and future success. This is what we mean by to the production plants. During the first half of 2014 AAK “responsible growth”. acquired Belgian oils and fats business CSM Benelux NV in We believe that building sustainability into our everyday Merksem and Fabrica Nacional de Grasas S.A. (FANAGRA), activities helps us achieve our vision of being the first choice a Colombian company that specializes in vegetable oils and in valueadding vegetable oil solutions. fats for the bakery segment. Data from these acquisitions is AAK’s model for responsible growth covers the five focus not included in this report. Data from our Brazilian factory in areas Marketplace, Supply chain, Environment, Workplace Jundiaí, São Paulo, whose production started in April 2015, is and Community. not included either. Throughout the report, AAK colleagues share stories about some of our many CSR initiatives. Top managers also share Global team effort their thoughts and insights in relation to their specific areas of responsibility. This report aims at providing a clear picture The annual production and release of our GRI Report is a of how we at AAK work with sustainability – our drive towards global team effort involving staff from various functions at all responsible growth. -

Co-Developing for a Sustainable Future

Co-developing for a sustainable future Sustainability Report 2018 Contents Introduction to AAK .................................................................................................... 2–5 Statement by CEO Johan Westman .......................................................................... 6–7 Sustainable growth at AAK ........................................................................................ 8–9 UN Global Compact commitments ............................................................................ 10–11 Contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals ............................................... 12–13 Global sustainability achievements 2018 .................................................................. 14–15 Our Customers .......................................................................................................... 16–23 Our Suppliers............................................................................................................. 24–39 Our Planet ................................................................................................................. 40–51 Our People ................................................................................................................ 52–57 Our Neighbours ......................................................................................................... 58–62 Our Suppliers, p. 24 Our Planet, p. 40 Sustainability approach ............................................................................................ -

Palm Oil: Report 34

Palm Oil Report Report 34 June 2021 1 Table of Contents Cases identified using Landsat and Planet imagery Indonesian Companies New Cases PT Tandan Sawita Papua: Eagle High Plantations Tbk (Rajawali group) 3 PT Gawi Makmur Kalimantan: Wings Agro 5 PT Brahma Binabakti : Triputra Agro Persada 7 Unresolved Cases PT Agincourt Resources Tbk: Astra International Tbk 9 Malaysian Companies New Cases LPF 0026: Rimbunan Hijau 11 Supply chain information: Supply chain information included in Rapid Response reports is based on the latest public versions of mill disclosures, recent export data, and company grievance logs. Mighty Earth encourages companies to send updated versions of mill disclosures as soon as they become available and to share any decision to suspend relations with a given group/company listed in those mill disclosures with [email protected]. Mighty Earth is now including biofuel companies and other manufacturers in the supply chain tables of Rapid Response reports, as these companies have both direct and indirect trading relationships with groups highlighted in these reports and should be filing grievances on these cases. These companies are listed in the “Supply Chain Information” tables. 2 New Case Group: Rajawali Group / Eagle High Plantations Tbk PT Tandan Sawita Papua Concession location: -2.955573, 140.862110 Deforestation and/or peat development Peat Peat forest Clearance Deforestation Report development development prep/Stacking Time period (ha) (ha) (ha) lines (ha) November 2020 - Report 34 58 - - - May 2021 Satellite imagery shows that between November 2020 and May 2021, a total of 58 hectares of forest were cleared in the PT Tandan Sawita Papua concession. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Carrie Livingston Email: [email protected] Phone: 815-519-8302

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Carrie Livingston Email: [email protected] Phone: 815-519-8302 AAK USA OPENS CUSTOMER INNOVATION CENTER IN RICHMOND CALIFORNIA (November 12, 2019) Edison, NJ – AAK USA Inc., one of the world’s leading manufacturers of value- adding specialty vegetable fats and oils, announced the opening of its newest Customer Innovation Center. The facility, located in Richmond, California supports co-development work with multiple industry segment-focused labs and houses AAK’s U.S. Center of Excellence for Plant-Based Foods. “AAK has over fifteen Customer Innovation Centers worldwide and has opened multiple locations across the U.S. over the last several years,” said Octavio Diaz de Leon, President of AAK USA and AAK North Latin America. “Our Richmond Customer Innovation Center investment offers an additional 2,000 square feet of co-development space and delivers on our commitment to providing our customer-partners coast- to-coast service and support. We accelerate innovation using AAK’s Co-Development approach, and our expansive team of fats and oils, bakery, dairy, plant-based foods and personal care experts, all coming together to create real-world formulation solutions.” “The addition of our Richmond Innovation Center allows AAK to bring specialty vegetable oil solutions to our West Coast customers in a very collaborative way,” said James S. Jones, Ph.D., Vice President Customer Innovation, Plant-Based Foods, AAK USA. “We test AAK solutions and prove them in our customer’s products, ensuring functionality before plant trials and production. Our experts evaluate the customer critical attributes of flavor, texture, appearance—and even sound—that impact the consumer’s organoleptic and emotional eating experience. -

AAK AB (Formerly Known As: Aarhuskarlshamn AB)

AAK AB (Formerly known as: AarhusKarlshamn AB) Particulars Organisation Name AAK AB (Formerly known as: AarhusKarlshamn AB) Corporate Website Address www.aak.com Primary Activity or Product Processor and/or Trader Related Company(ies) Company Primary RSPO Activity Member AarhusKarlshamn Sweden Processor and/or Yes AB Trader AarhusKarlshamn Processor and/or Yes Denmark A/S Trader AarhusKarlshamn USA Processor and/or Yes Inc. Trader Oasis Foods Company Manufacturer Yes AarhusKarlshamn UK Ltd Processor and/or Yes Trader AarhusKarlshamn Mexico Processor and/or Yes SA de CV Trader AarhusKarlshamn Processor and/or Yes Netherlands NV Trader AAK Turkey Yes AAK Belgium Manufacturer Yes AarhusKarlshamn China Processor and/or Yes Ltd Trader AarhusKarlshamn do Processor and/or Yes Brazil DdN Ltd Trader AarhusKarlshamn Processor and/or Yes Asia-Pacific Sdn. Bhd. Trader AarhusKarlshamn Latin Processor and/or Yes America S.A. Trader Country Operations Belgium, Brazil, China, Colombia, Denmark, Mexico, Netherlands, Sweden, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States, Uruguay Membership Number 2-0001-04-000-00 Membership Type Ordinary Members Membership Category Palm Oil Processors and Traders Particulars ACOP 2013/2014 - AAK AB (Formerly known as: AarhusKarlshamn AB) Palm Oil Processors and Traders Operational Profile 1.1 Please state your main activity(ies) within the supply chain ■ Refiner of CPO and CPKO ■ Post-refinery processor ■ Trader ■ Ingredient manufacturer ■ Animal feed supplier Other: -- 1.2 Operation and Certification Progress -- 1.2.1 Do you have -

AAK Magazine

Insight AAK Magazine The Co-Development Company #3, November 2016 Responsible growth at AAK, pages 3–9 AAK USA goes west, pages 10–11 In the land of the rising sun, pages 12–13 Dear readers, A very warm welcome to AAK’s customer magazine Insight. The Co-Development Company In this issue we will pay some extra attention to the impor- Furthermore, we give you a couple of concrete examples tance of corporate social responsibility. of what it means to be the Co-Development Company. To act responsibly is both a shared and an individual We have asked colleagues from different parts of the obligation, and as a global company AAK works hard to organization to share some of their recent co-development do its parts to the highest possible standards. Responsible stories, and to explain how our customer value propositions growth is furthermore a key objective of our strategy and for health and reduced costs have helped our customers essentialtobeingourcustomers’firstchoiceforvalue- improve and grow their businesses. adding vegetable oil solutions. If you have any comments or questions about the content TodriveprogresswithinCSRwefocusoureffortsinfive of the magazine or if you have suggestions for future articles areas – Marketplace, Supply chain, Environment, Workplace of Insight, please don’t hesitate to talk to your AAK represen- and Community – which are explained in more detail in this tative or contact us via [email protected]. magazine. We also present a few of our sustainability initia- tives within these areas.