Locational Behavior of Firms in a Borderless Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Politics of Foreshore Reclamation in Tagbilaran City: the Emerging Prospects and Challenges

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS AND FINANCE STUDIES Vol 9, No 1, 2017 ISSN: 1309-8055 (Online) CURRENT POLITICS OF FORESHORE RECLAMATION IN TAGBILARAN CITY: THE EMERGING PROSPECTS AND CHALLENGES Prof. Erika Barbarona Holy Name University [email protected] Dr. Frederico B. Ticong Holy Name University [email protected] Maeveen Marie R. Durban Holy Name University [email protected] Minette Almedilla Holy Name University Elne Galon Holy Name University -Abstract- The study aimed to assess the current status of foreshore reclamation in the City of Tagbilaran. The City of Tagbilaran sets the demands of the increasing urbanization, facing the challenge of economic expansion in foreshore areas. Using the quantitative and qualitative method, the researchers were able to assess the current politics of foreshore reclamation based on the analysis of its emerging challenges and prospects. The data revealed that the respondents have seen the challenge of having an increase of transportation and population explosion that would result to high level of noise and disturbance of the ecosystem and nature. The possibility of a highly competitive and more urbanized city, expanding infrastructure, more workers creating economic stability and new attractions does not compensate the challenges. The researchers found out that businessmen who are in the government are holding back the people in deciding about the existence of foreshore reclamation. In fact, there are still more public land areas available to 48 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS AND FINANCE STUDIES Vol 9, No 1, 2017 ISSN: 1309-8055 (Online) utilize and develop that would not lead them to resort for foreshore reclamation. Hence, people in Tagbilaran City were not yet ready to become a highly urbanized city. -

Cebu 1(Mun to City)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Cebu Province i Map of Cebu City ii - iii Map of Mactan Island iv Map of Cebu v A. Overview I. Brief History................................................................... 1 - 2 II. Geography...................................................................... 3 III. Topography..................................................................... 3 IV. Climate........................................................................... 3 V. Population....................................................................... 3 VI. Dialect............................................................................. 4 VII. Political Subdivision: Cebu Province........................................................... 4 - 8 Cebu City ................................................................. 8 - 9 Bogo City.................................................................. 9 - 10 Carcar City............................................................... 10 - 11 Danao City................................................................ 11 - 12 Lapu-lapu City........................................................... 13 - 14 Mandaue City............................................................ 14 - 15 City of Naga............................................................. 15 Talisay City............................................................... 16 Toledo City................................................................. 16 - 17 B. Tourist Attractions I. Historical........................................................................ -

Protection of the Groundwater Resources of Metropolis Cebu (Philippines) in Consideration of Saltwater Intrusion Into the Coastal Aquifer

17th Salt Water Intrusion Meeting, Delft, The Netherlands, 6-10 May 2002 489 PROTECTION OF THE GROUNDWATER RESOURCES OF METROPOLIS CEBU (PHILIPPINES) IN CONSIDERATION OF SALTWATER INTRUSION INTO THE COASTAL AQUIFER Olaf SCHOLZE (a), Gero HILLMER (b) and Wilfried SCHNEIDER (a) (a) Technical University of Hamburg-Harburg, Department of Water Management and Water Supply, Schwarzenbergstr. 95, 21073 Hamburg, GERMANY, [email protected] (b) University of Hamburg-Harburg, Department of Geology and Paleontology, Bundesstr. 55, 20146 Hamburg, GERMANY INTRODUCTION The world, particularly the developing countries, is experiencing shortages of potable and clean waters. For the effective management of water resources it is necessary to understand the natural systems affecting the groundwater. Saltwater intrusion is common in coastal areas where aquifers are in hydraulic contact with the sea. A zone of contact (salt-freshwater interface) is formed between the lighter freshwater flowing to the sea and the heavier, underlying, seawater (specific weight γs > γf). Even under natural conditions without any anthropogenic activity the freshwater from the aquifer flows into the sea (outflow face), while in greater depth saline water penetrates into the pore space of the aquifer. The saltwater wedge at the bottom of an aquifer may move long distances against the natural gradient of the freshwater table. Additional pumping of groundwater induces upconing and further movement of seawater inland towards the groundwater extraction (Figure 1). The mixing of seawater with groundwater affects the quality and the normal usefulness of groundwater. Natural replenishment Zone of pumping Water table Sea Initial water table Outflow Freshwater face f Interface Saltwater Initial interface S able Imperme Figure 1 Cross-section in a coastal aquifer with saltwater upconing. -

The Case of Tagbilaran City, Bohol

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics del Prado, Fatima; Acejo, Iris L.; Remolino, Darlyne Working Paper Tourism Fuels an Emerging City: The Case of Tagbilaran City, Bohol PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2004-53 Provided in Cooperation with: Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Philippines Suggested Citation: del Prado, Fatima; Acejo, Iris L.; Remolino, Darlyne (2004) : Tourism Fuels an Emerging City: The Case of Tagbilaran City, Bohol, PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2004-53, Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Makati City This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/127878 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas Tourism Fuels an Emerging City: The Case of Tagbilaran City, Bohol Iris Acejo, Fatima del Prado and Darlyne Remolino DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. -

The Metro Cebu Environmental Improvement Project

THE METRO CEBU ENVIRONMENTAL IMPROVEMENT PROJECT By: Jun Erasmo E.Villafañe Officer-in-Charge, Environmental Technical Services Division Environmental Management Bureau – Region 7 Republic of the Philippines (Paper presented during the First Meeting of the Kitakyushu Initiative Network for a Clean Environment, Kitakyushu City, 20-21 November 2001) I. METRO CEBU PERSPECTIVES General Information The island Province of Cebu is located in Central Philippines, about 600 km south of Manila, the country’s capital. Metropolitan Cebu, where economic activity is concentrated, is a coastal urban sprawl comprising four (4) cities of Cebu, Mandaue, Lapu-lapu and Talisay; and six (6) municipalities of Compostela, Lilo-an, Consolacion, Cordova, Minglanilla and Naga. It has an approximate total land area of 74,209 hectares (Metro Cebu Ecological Profile, Filteknik Inc.). Metro Cebu’s population was estimated at 1.3 million in 1990 and projected to reach 2.3 million by year 2010 (PCEEM Project Report, June 1998). It hosts at least 70% of the approximately 1000 industries in Region 7. Records from the Land Transportation Office-Region 7 showed that in 1994 there was a total of 124,561 registered motor vehicles. During the 5-year period from 1990-1994, an average annual increase of 11.5 % was also noted. Motor vehicles have been identified as a major source of air pollution in the country. As of 1998 Metro Cebu’s water demand is estimated at 234,000 cum. per day, rapidly increasing to 375,000 cum. per day by year 2010. Main source of water supply for domestic and industrial use is groundwater, deriving mainly from the coastal limestone aquifer and alluvial water-bearing formation in the river deltas of five rivers, namely: Kotkot River, Cansaga River, Butuanon River, Mananga River and Pangdan River. -

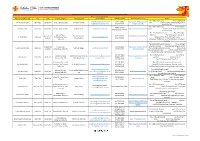

List-Of-Transiting-Hotels.Pdf

TRANSITING HOTELS FOR RETURNING OVERSEAS FILIPINOS (ROFs) and BALIKBAYANS (As 21 of September 2021) Name of Establishment City Type Complete Address Contact Person Email Address Mobile Number Online Booking Portal Rates Php 1,888, Single room Php 2,688, Double [email protected]/ 09054772382/ http://www.facebook.com/F Felicity Island Hotel Lapu-Lapu Quarantine Basak, Lapu-Lapu City Honeylou Amores room with full boardt, additional Php 800 for [email protected] 09323640737 elicityIslandHotel airport transfers Php 1,800, single room, Php 2,500 twin 09178217154/ Dulcinea Hotel Lapu-Lapu Quarantine Pusok, Lapu-Lapu City Rowela Aguro [email protected] http://www.dulcineahotel.ph room, all rates include fullboard meals and 09064722628/ 495.2741 airport transfers Php 1500/night (superior) Php 1750 /night Queens Road, (deluxe) Php 1950/night (Deluxe plus) Quarantine/ Gieselle Abinales/ 09177107863/ https://www.stmarkhotel.ph St. Mark Hotel Cebu City Redemptorist Plaza, [email protected] Additional Php 750 for full board meals; Isolation Eunice Cadavis 09177294132 / Cebu City additional Php 800 (car) and Php 1500 (van) for airport transfers Php 2,100/night (Single), Standard Php 2,700/night (double), Standard Php 2,400/night (Single), Deluxe Quarantine/ N. Escario St. 032.520.2222/ http://www.facebook.com/e Escario Central Hotel Cebu City Merry An Alegre [email protected] Php 3,000/ngiht (double), Deluxe Rates include Isolation Kamputhaw, Cebu City 09177169981 scariocentralhotel full-board packed meals Airport Transfer (one-way): Php 900 (car), Php 1200 (Innova), Php 1500 (van) 032.402.5999/ Php 3,100.00 (single) Php 4,000.00 Archbishop Reyes Kristal Manalang-Catarroja/ cebuallreservation@questhotelsa https://questhotelsandresort Quest Hotel Cebu City Multi-Use 09989615734/ (double) Full board meals Avenue, Cebu City Mariel Daug-daug ndresorts.com s.com/cebu/ 09174017844 Php 750.00/way airport transfers #6 Junquera Ext cor R.R. -

Contribution of Infrastructure to Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction

Contribution of Infrastructure to Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction Japan Bank for International Cooperation Republic of the Philippines Comprehensive Impact Study for Metro Cebu Development Final Report March 2004 Global Group 21 Japan, Incorporated Introduction This report was prepared by Global Group 21 Japan, Inc. to investigate the Comprehensive Impact Study for the Metro Cebu Development Project on commission from the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (hereinafter referred to as “JBIC”) in the year 2004. The subject of this study, “Metro Cebu”, is the second largest city in the Philippines to which JBIC had provided assistance surpassing well beyond 100 billion yen in total. In the light of its accountability to the Japanese public and the importance of feeding back lessons for its future projects, JBIC conducts evaluation of its projects every year. At the same time, JBIC recognizes the importance of evaluation not only from an individual but also from a comprehensive viewpoint. Therefore, JBIC initiated this comprehensive impact study for a number of different yen-loan projects in Metro Cebu since the 1970s. In this study, the development planning process for Metro Cebu has been divided into three development cycles for purposes of analyses and organization, namely: (1) the first cycle (1978-1986) which covered the period of the physical development planning of regional growth centers; (2) the second cycle (1987-2003) during which regional urban development for sustainable growth was promoted; and (3) the third cycle (2004 and beyond) which envisions the dispersion of growth away from Metro Cebu. This study evaluated the impact of a number of different yen-loan projects in the Metro Cebu area using the “Urban Development Model” concept. -

©2011 Charles Donald Mcglynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2011 Charles Donald McGlynn ALL RIGHTS RESERVED AN ISLAND ENVIRONMENT: SALTWATER INTRUSION, GROUNDWATER MANAGEMENT AND WATER PRIVATIZATION IN CEBU By CHARLES D. MCGLYNN A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Geography Written under the direction of Dr. Robert Hordon And approved by _________________________________ _________________________________ _________________________________ _________________________________ _________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2011 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION An Island Environment: Saltwater Intrusion, Groundwater Management and Privatization in Cebu By CHARLES DONALD MCGLYNN Dissertation Director: Dr. Robert M. Hordon “A nation that fails to plan intelligently for the development and protection of its precious waters will be condemned to wither because of its short sightedness” (Johnson 1968) In the midst of this “Decade of Water”, the Philippines is faced with one of its major cities plagued by water problems for the same shortsightedness that President Lyndon Johnson described in 1968. The fact that this city is in a humid climate rather than a parched one makes the neglect that much more compelling. As Matthew Gandy (2003) states in Concrete and Clay, “the history of cities can be read as a history of water”. As this research indicates, Cebu City is no exception. Cebu is the second largest city in the Philippine archipelago and is an ideal place to study these issues for several reasons. It is continuing to experience strong population growth. Also, by all accounts the groundwater in this metropolitan area of over two million people is rapidly deteriorating due to saltwater intrusion. -

Metro Cebu JICA: Traffic Congestion Now Costs P3.5 Billion a Day in Metro Manila

Metro Cebu JICA: Traffic Congestion now costs P3.5 Billion a day in Metro Manila Source: Traffic still a nightmare in Metro Cebu Source: By Victor Anthony V. Silva – Reporter / @VicSilvaCDN Philippine Daily Inquirer / 07:28 AM July 05, 2017y 05, Sept 2016 at Pope John Paul II Ave Nov 2017 N. Bacalso Ave December 2017 Tabok, Mandaue City July 2017 Osmeña Bridge, Lapulapu City Education Engineering Enforcement +2 Enactment of Laws Environment 1. Urbanized cities intensified its respective traffic education to all road users 2. Synchronization of traffic codes; drafting of new traffic management codes; amending present traffic codes 3. Capacitating traffic enforcers through traffic enforcement trainings; sharing of best practices; formulating common short- term goals for traffic management 4. Standardization of traffic control devices following MUTCD 5. Installation of additional traffic control devices and intelligent traffic management systems to further strengthen road safety and traffic enforcement 6. Enhanced the coordination and cooperation among the LGUs in Metro Cebu in case inter- LGU traffic-related problems will occur 7. Strict and consistent implementation of the traffic code provisions and other traffic-related ordinances 8. Creation of the Mega Cebu Traffic Enforcers Academy (MCTEA) to professionalize the traffic enforcement personnel 9. Establishment of the Metro Cebu Truck Corridor Submission of Traffic Code MEGA CEBU LGUs Contact Person (as of February 2018) Cebu City Submitted Atty. Ismael Garaygay III Danao City Amendments for approval by the Council Alfredo C. Tapia (Ret.) Mandaue City Submitted Mr. Glenn Antigua Lapulapu City No Traffic Code Mr. Mario M. Napule Consolacion Submitted Feliculo J. Leciones (Ret.) Compostela Submitted SPO1 Arthur Ariate Minglanilla Amendments for approval by the Council Mr. -

Applying Hazard Maps to Urban Planning

Applying Hazard Maps to Urban Planning September 10th, 2014 SAKAI Yuko Disaster Management Expert JICA Study Team for the Metro Cebu Roadmap Study on the Sustainable Urban Development 1 Contents 1. Outline of Metro Cebu Roadmap Study 2. Development of GIS Database 3. Methodology of Development Suitability Analysis 4. Preparation of Thematic Maps 5. Overlay Analysis 6. Necessary Actions 2 1.1 Roadmap Toward The Vision Vision Roadmap 1. Metropolitan Development Framework 2. Roadmap Development Plans 3. Short-term Priority Projects 3 1.2 Objectives of the Study 1. To draw up a roadmap and detailed action plans based on “Mega Cebu Vision 2050” with time- framework of: Short-term (2016), Med-term (2020), and Long term (up to 2030 up to 2050) 2. To formulate priority projects in association with institutional and organizational options for the materialization 4 1.3 Study Area The study area covers Metro Cebu consisting of 13 LGUs : • 7 cities (Cebu, Danao, Mandaue, Lapu-Lapu, Talisay, Naga and Carcar) and • 6 municipalities (Compostela, Metro Cebu Liloan, Consolacion, Cordova, Minglanilla and San Fernando). 72 km Danao, San Fernando and Carcar are new comers to the old Metro Cebu boundary 5 1.4 DEMOGRAPHIC FRAME Land Area Population Growth Population Rate (%/year) LGUs 2 (km ) 2000 2007 2010 ’00-‘07 ’07-‘10 Cebu 315 718,821 798,809 866,171 1.5 2.7 Lapu-Lapu 58 217,019 292,530 350,467 4.4 6.2 Mandaue 25 259,728 318,575 331,320 3.0 1.3 Talisay 40 148,110 179,359 200,772 2.8 3.8 Cities Danao 107 98,781 109,354 119,252 1.5 2.9 Carcar 117 89,199 100,632 107,323 1.7 2.2 Naga 102 80,189 96,163 101,571 2.5 2.2 Compostela 54 31,446 39,167 42,574 3.2 2.8 Consolacion 147 62,296 87,544 106,649 5.0 6.8 Cordova 17 34,032 45,066 50,353 4.1 3.8 Liloan 46 64,970 92,181 100,500 5.1 2.9 Minglanilla 66 77,268 101,585 113,178 4.0 3.7 Municipalities San Fernando 69 48,235 54,932 60,970 1.9 3.5 Metro Cebu 1,163 1,930,096 2,314,897 2,551,100 2.6 3.3 Philippines 343,448 76,506,928 88,566,732 92,337,852 2.1 1.4 Source: PS 6 2. -

Metro Cebu Market Update 2H 2018

RESEARCH METRO CEBU MARKET UPDATE 2H 2018 METRO CEBU REAL ESTATE SECTOR REVIEW CEBU REGAINS ATTRACTIVENESS AS A GO-TO SPOT FOR BUSINESS AND LEISURE ACTIVITIES COVER | Investments and Tourism further drive Metro Cebu’s growth in the second half of 2018 Heavy business and construction investments is noted in the fringes Exciting investment prospects activities in Metro Cebu are and surrounding cities. A great deal abound Metro Cebu, backed by the primarily observed in three of the of business and investments continuously growing local and area’s major cities, Cebu City, activities have been detected in regional economy, newly opened Mandaue City and Lapu-Lapu City. Mandaue City in particular. The Mactan-Cebu International Airport Cebu City has consistently been property sectors in Mandaue were (MCIA) and other proposed one of the preferred outsourcing perceived to be growing at a government infrastructure destinations in the world. Coming remarkable rate, following the low developments. Bridges designed to from the 12th spot in 2017, Cebu vacancies and almost full saturation connect Cebu to the other nearby City rose a level up to the 11th spot of Cebu City. islands, such as Bohol and Negros, of the latest Top 100 Super Cities are expected to further enhance the list released by Tholons, a Aside from boasting of a good ease of doing business between renowned international strategic business environment, Cebu Metro Cebu and adjacent areas. In advisory firm. The competitive talent continues to attract local and addition, road networks in the pool and cheap labor cost remain foreign tourists with the various pipeline will facilitate a smoother as major considerations in choosing leisure activities that could be done travel experience from Danao City in Cebu City over other locations. -

Information Dissemination and Communication in Stakeholder Participation: the Bohol-Cebu Water Supply Project

Asia Pacific Viewpoint, Vol. 40, No. 3, December 1999 ISSN: 1360-7456, pp251–269 Information dissemination and communication in stakeholder participation: the Bohol-Cebu water supply project Karen T. Fisher and Peter B. Urich Abstract: Development theories in the 1990s embrace a much more people-centred perspective than in previous decades. At the same time, foreign direct investment is increasingly being touted as a new form of development assistance, and transnational corporations as new aid agents. However, the ideology of the free market is incongruous with the people-centredness of contemporary development theory. The result is a polarisation between participatory development and market driven paradigms. This study introduced the models of instrumental and transformative participation and the way they influence information flow and communication. These models are used to examine a project proponent’s and stakeholder’s actions in a privatised development setting, using a Philippine case study. The case study is the Bohol- Cebu water supply project, a project of water capture, treatment, and transmission, linking the islands of Bohol and Cebu. Communication and information dissemination between the project proponent and stakeholders is viewed under the requirements of Philippine legislation for participation in development. The findings from this research suggest that the proponent tended to exclude or only partially include affected stakeholders in the development process. Sources of information were often nongovernmental organisations, the Church, and, in many instances, the media. The proponent’s method of disseminating information was primarily to target the municipal or provincial government level, thus disenfranchising the `grass roots'. Keywords: Philippines, development, stakeholder participation, information dissemination, communication.