M. M. M. Hayes Lay of the Land

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July2010catalog-Web.Pdf

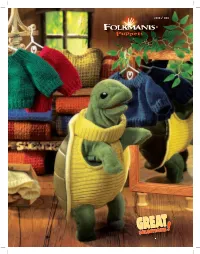

2010 / 2011 Award Winner Grizzly Brown Bear Moose Fawn 13" (33 cm) long Black Bear Cub Bear Cub 17" (43 cm) long 2841 22" (55 cm) long 2205 2573|| Does not stand up alone 14" (35 cm) tall 2831 17" (43 cm) long 2138 as shown. Does not stand alone as shown. mini Moose Award Winner 6" (15 cm) long 2719 mini Black Bear 6" (15 cm) long 2641 mini Award Winner Fawn Sequoia 6" (15 cm) long 2733 Tree Wildlife Play Set 17" (43 cm) tall 5006 Tree puppet includes six wildlife finger puppets. Baby Black Bear Front cover 9" (22 cm) tall 2232 Turtleneck Turtle 12" (30 cm) tall 2881 Does not stand alone as shown. 2 3 Small Red Fox Coyote 15" (38 cm) long 15" (38 cm) tall 2576 2226 Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing Stage Puppet Fox 16" (40 cm) tall 2859 Stage Puppet Removable sheepskin. 16" (40 cm) tall 2598 Timber Wolf 18" (45 cm) long Award Winner 2171 mini Fox 6" (15 cm) long 2644 Wolf 23" (58 cm) long 2101 Fox 20" (50 cm) long 2049 Red Fox 20" (51 cm) long 2876 Bobcat 15" (38 cm) tall 2199 4 4 5 mini Weasel 9" (20 cm) long 2720 Award Winner mini Skunk 8" (20 cm) long 2647 Raccoon Stage Puppet 15" (38 cm) tall 2596 Beaver Skunk 18" (45 cm) long 2245 15" (38 cm) long 2250 Award Winner Porcupine 13" (33 cm) long 2378 Award Winner Award Winner mini Beaver mini 7" (17 cm) long 2651 Raccoon 8" (20 cm) long 2646 Award Winner mini Porcupine Award Winner 5" (12 cm) long 2649 Raccoon in Garbage Can 10" (25 cm) tall 2321 River Otter Baby Raccoon Raccoon pulls into can. -

1 GENETICS and PATTERNS of INHERITANCE Simon Petersen

GENETICS AND PATTERNS OF INHERITANCE Simon Petersen-Jones DVetMed PhD DVOphthal MRCVS DECVO Department of Small Animal Clinical Science Michigan State University Veterinary Medical Center 736 Wilson Road, D-208 East Lansing. MI 48824 [email protected] INTRODUCTION The genome contains a complete set of instructions to make an organism and control its cellular structures and activities. This information, or genome, is contained within tightly coiled threads of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) found in the nucleus of every cell. The DNA is divided into chromosomes. The human genome consists of about 3 billion basepairs (Mb) (dog genome consists of 2.4Mb) and disease may result from an alteration of just one of those basepairs. It is estimated that the human genome contains in the region of 20, - 25,000 genes, whereas the dog is estimated to have only ~19,000 genes. Each gene carries the code for making a particular protein. Only a subset of the total number of genes will be functional in a particular cell type. Certain genes, known as house-keeping genes are expressed in all cell types and are needed for cell function. Other genes are tissue or cell-type specific. Although 20 –25,000 may seem a small number of genes to encode for and control the functions of a complex organism, further complexity if provided by a process of alternative spicing of genes. Alternative splicing between different tissues allows the same gene to produce differing proteins dependent on the tissue in which the gene is active. From http://www.exonhit.com/alternativesplicing/index.html - see this web page for more information on alternative splicing. -

DOE Human Genome Program Contractor-Grantee Workshop VI November 9-13, 1997 Santa Fe, New Mexico

CONF-971146 DOE uman ~ ~enome Contact for queries about this publication: Human Genome Program U.S. Department of Energy Office of Biological and Environmental Research ER-72GTN Washington, DC 20585 301/903-6488, Fax: 301/903-8521 E-mail: [email protected] A limited number of print copies are available. Contact: Betty K. Mansfield Oak Ridge National Laboratory 1060 Commerce Park, MS 6480 Oak Ridge, TN 37830 423/576-6669, Fax: 423/574-9888 E-mail: [email protected] An electronic version of this document will be available, after the November 1997 meeting, at the Human Genome Project Information Web site under Publications (http://www.ornl.gov/hgmis). This report has been reproduced directly from the best obtainable copy. Available to DOE and DOE contractors from the Office of Scientific and Technical Information; P.O. Box 62; Oak Ridge, TN 37831. Price information: 423/576-8401. Available to the public from the National Technical Information Service; U.S. Department of Commerce; 5285 Port Royal Road; Springfield, VA 22161. CONF-971146 DOE Human Genome Program Contractor-Grantee Workshop VI November 9-13, 1997 Santa Fe, New Mexico Date Published: October 1997 Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Research Office of Biological and Environmental Research Washington, D.C. 20585 under budget and reporting code KP 0404000 Prepared by Hwnan Genome Management Information System Oak Ridge National Laboratory Oak Ridge, 1N 37830-6480 Managed by LOCKHEED MARTIN ENERGY RESEARCH CORP. for the U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY UNDER CONTRACT DE-AC05-960R22464 Contents Introduction to Contractor-Grantee Workshop VI ............................. -

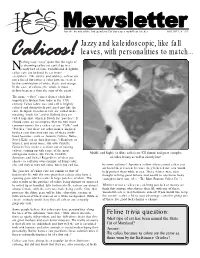

Jazzy and Kaleidoscopic, Like Fall Leaves, with Personalities to Match

For the friends of the Independent Cat Society, a no-kill cat shelter Fall 2011, # 134 Jazzy and kaleidoscopic, like fall leaves, with personalities to match... othing says “cozy” quite like the sight of a charming calico cat curled up in a Ncomfy ball of color. Colorful and delightful, calico cats are beloved by cat lovers everywhere. Like torties and tabbies, calicos are not a breed but rather a color pattern, created by the combination of white, black, and orange. In the case of calicos, the whole is most definitely greater than the sum of the parts! The name “calico” comes from a cloth first imported to Britain from India in the 17th century. Calico fabric was and still is brightly colored and distinctively patterned just like the cats. In Japan, tri-colored cats are called mi-ke, meaning “triple fur,” and in Holland they are called lapjeskat, which is Dutch for “patches.” It should come as no surprise that the two most common names for a calico cat are “Callie” and “Patches,” but there are other names inspired by their coat that may suit one of these multi- hued beauties, such as Autumn, Calista, Dottie, Jewel, Kalie (as in “kaleidoscope,”) Rainbow, or Sunset, and many more. Our own Paulette Gonzalez has made a science out of naming calicos, coming up with some of the most outrageous names, like Fiesta, Confetti, Maddie and Sophie (a dilute calico) are ICS alumni, and great examples Spumoni, and Salsa! Regardless of what you of calico beauty, as well as sisterly love! choose to call your own example of living color, she still may or may not come when you call her. -

THE PLIGHT of BLACK CATS and DOGS by Danielle Wallis

IN THIS ISSUE... KAR Friends May 2009 The Plight of Black Dear Reader, Cats and Dogs Special Event...Do- Did you know dark-colored dogs and cats have an even harder time of getting Dah Parade adopted? Our feature story talks about the plight of black animals and what you can do to help. Behind the Scenes with Tamsie Haskell This month’s Doggie Den tells the rescue and adoption story of Bear, a black Lab mix. Our Cat’s Corner provides useful information about why it is so important to keep your Doggie Den ~ cats indoors and how to keep them content. Loveable Bear Cat’s Corner ~ Reasons to Keep Cats Danielle Wallis Lynn Bolhuis Indoors and How to KAR Marketing Coordinator KAR Friends Editor Keep Them Content P.S. Keep watch in your mailbox for our special Spring Edition newsletter filled with OUR SPONSORS more great rescue and adoption stories. If you are not on KAR’s mailing list, feel free to send us an email with your name and address. THE PLIGHT OF BLACK CATS AND DOGS By Danielle Wallis Every pet adoption is a life saved, but in the case of black cats and dogs, you’re saving a life that’s at an even higher risk of being cut short. ~ Sarah It is an unfortunate and sad fact that color, black to be specific, contributes to hundreds of cats and dogs being euthanized each year. It is known among rescue groups as the Black Cat and Dog Syndrome, and these animals become the unfortunate victims of this tragic problem. -

2016 Fall Holiday 2016/17

CUDDLE TOYS 1956 ~ Celebrating 60 Years of Smiles ~ 2016 Fall Holiday 2016/17 [email protected] Princess Horses 763 RAINBOW PRINCESS HORSE 12” / 30 CM TALL BRUSH INCLUDED! 1 FANTASY CUDDLE TOYS 764 GOLDEN PRINCESS UNICORN 762 WARRIOR PRINCESS HORSE 12” / 30 CM TALL 12” / 30 CM TALL 760 FLOWER PRINCESS HORSE 761 TRIBAL PRINCESS HORSE 12” / 30 CM TALL 12” / 30 CM TALL BRUSH INCLUDED! [email protected] 2 Fantasy Horses & More 1139 MARINA AQUA SPARKLE 1147 GEM PINK SPARKLE 4068 SERAFINA UNICORN 1143 CRYSTAL PURPLE SPARKLE 7” / 18 CM TALL 7” / 18 CM TALL 7” / 18 CM TALL 7” / 18 CM TALL 4054 PAX UNICORN 738 BUTTERFLY PINK HORSE 4555 RAINBOW WHITE HORSE 8” / 20 CM TALL 8” / 20 CM TALL 8” / 20 CM TALL 340 FILOMENA WHITE HORSE 4000 STARRY NIGHT WHITE HORSE 27” / 69 CM LONG 12” / 30 CM TALL 3 FANTASY CUDDLE TOYS 1684 SUNBEAM UNICORN 327 GRACE WHITE HORSE 12” / 30 CM TALL 22” / 56 CM LONG 736 JEWEL PEGASUS 12” / 30 CM TALL 343 ABRACADABRA UNICORN 27” / 69 CM LONG 669 PETUNIA BALLERINA MOUSE 9” / 23 CM TALL 2161 FANTASY UNICORN PET SAK 2151 PURPLE TUTU MOUSE PET SAK 4283 PETUNIA BALLERINA MOUSE 7” / 18 CM WIDE 7” / 18 CM WIDE 20” / 51 CM TALL [email protected] 4 Sparkly Sea Friends 15384 PINK SEAHORSE 15385 AQUA SEAHORSE 1545 OLIVIA PINK MERMAID 1553 CALYPSO LIME MERMAID 10” / 25 CM TALL 10” / 25 CM TALL 12” / 30 CM TALL 12” / 30 CM TALL 3758 BENNY BLUE DOLPHIN 12.5” / 32 CM LONG 1565 ROSI PINK DOLPHIN 9” / 23 CM LONG 1564 SILVIE BLUE DOLPHIN 9” / 23 CM LONG 1571 SPIKE JR BLUE NARWHAL 12” / 30 CM LONG 4129 SPIKE BLUE NARWHAL 15” / 38 CM LONG 5 SEA CUDDLE -

The Animal Health Magazine

THE ANIMAL HEALTH MAGAZINE ( A BICENTENNIAL SALUTE TO HORSES AND RFDERS AT LEXINGTON & CONCORD UNDERSTANDING YOUR DOGS BEHMflOR PAR FIRST AID TIPS FOR YOUR FAVORITE PET 1VD 'VU3AIU OOld 09906 eiuJO|i|eo ZPZ ON imu3d 'BieAj y oojd aivdaovisod sn pjeA9|nog peawasou 8EC8 OdO lldOdd-NON uojiepunoj MlieaH lewmy fffffffffffffffffff Official Journal of the Animal Health Foundation on animal care and health. JAN/FEB 1976 Volume 7 Number 1 ARTICLES EDITOR'S NOTEBOOK How About a Career in Veterinary Medicine?, Raymond Schuessler ... 8 Coprophagy, Joyce O 'Kelley 9 A Cavalcade Bicentennial Salute to the Anti-Cruelty Society of Chicago . 10 This is the official beginning of the Canine Behavior- Part II, Michael W. Fox, M.R. C.V.S.,Ph.D 12 BICENTENNIAL year of 1976! Every Veterinary College Open House 14 where we go, everything you see Cavalcade Salutes America's 200th Year - A Special Bicentennial Account written has reminders of this memor on the Horses and Riders at Lexington & Concord, April 19, 1775 able year. Not many of us will see Everett B. Miller, V.M.D 16 another centennial, so let's celebrate it A Bicentennial Tribute to the Noble Mule, D. A. Woodliff 19 while we can and the best way we can. What Happened to Monkeynaut Baker? 21 We are privileged to have a How to Cut the High Cost of Cat Litter, Manuel Castlewitz 20 veterinary historian write an authentic Pet Care - The Dog 24 account of the struggles at Concord. Ruffian - What Really Happened?, Wayne O. Kester, D. V.M. 25 This will be presented in a series A Few Notes on First Aid, Thomas Dunn 26 during the next several issues of Psyching Out the Uncommon Cat, Stephen Nagy 30 Animal Cavalcade. -

REX the KING the Rex Cats, So New to the Fancy That Many Fanciers Who

REX THE KING By Helen Weiss The Rex cats, so new to the fancy that many Fanciers who show, and even some of the judges have never seen one, are of the most out standing breed. Most new breeds and colors are man made by hybridiz ing between two or more breeds and work ing with them until the desired character istics are obtained. This is not true with the Rex for it is a mutation from the Do mestic Shorthair and can be obtained only when both parents carry the rex gene or by the original mutation created by God. Many think that a Rex cat is just cat without guardhairs. This is not true for these cats, even in the first mutation, are as unlike their normal coated siblings as they can be. Almost without fail these cats show a definitely foreign type. The differ ence is best seen in the illustration of the Rex cat from Ohio and his litter brother. The Rex are outstanding in appear ance, their most distinguishing characteristic being' their short, dense and usually curly coat that is so soft. to the touch that one can never forget the feel of this luxurious fur. This fur is different from that of the normal cat, for it has no g'uard hairs, with the und~r coat or down hairs shorter and finer but more numerous than the hall' on any other breed. 1 Rex cats have a delicate appearance which belies their heavy weight and muscular body. Most Rex cats are fine boned and slim in appearance, but part of this is an illusion created by the very short coat, so that one is able to see the muscle forms that are covered by a longer coat in other cats. -

BURN 2011 Why Are Cloned Cats Not Identical, Implications for Pet Cloning and Public Perception by Emma Catherine Stubbs Supervisor Prof

BURN 2011 Why Are Cloned Cats Not Identical, Implications For Pet Cloning And Public Perception By Emma Catherine Stubbs Supervisor Prof. Keith Campbell Figure 1. showing (a) nuclear donor and (b) cloned kitten with surrogate, reprinted from Shin et al. (2002). Introduction Cloning is a breeding technique used to produce animals (especially cats) are unlikely to have the offspring via asexual reproduction. This means same markings . that only one parent is needed and the offspring; The first aim of the investigation was to look at the termed a clone, is very nearly genetically identical genetics of cat coat colour and explain the to the original, (Winter et al., 2002). The technique began to emerge in 1952, however since the mechanisms that cause the differences. The cloning of the first mammal (Dolly the Sheep) in second aim was to look at the public perception of 1996, there has been increasing interest in cloning cloning by conducting a survey. The aims of the pet animals, (Westhusin, 2000). survey were to identify whether the public had heard about cloning, to identify how many would be prepared to clone their pet and the main Genetically identical offspring are found reasons for their views. The final aim of the throughout the natural world. In non humans this occurs via asexual reproduction and in humans it investigation was to use the results of the survey occurs through the production of twins. However, to investigate whether pet cloning is likely to have in the laboratory a clone is produced via a a commercial future. technique called somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). -

CALICO ACHIEVEMENTS Work Your Way up the Achievements Chart to Become a Calico Quilt Master! Calico Achievement Points Can Be Earned and Tracked As You Play Calico

™ Rulebook ™ A competitive quilt-making, cat-collecting, tile-laying game by Kevin Russ, for 1-4 players, ages 14+ In Calico™, players compete to sew the coziest quilt as they draft and place patch tiles of different colors and patterns onto their quilt board. Each board will include 3 design goal tiles that will earn points if their requirements are met. Players are also trying to create pattern groups to attract the cuddliest cats and groups of colors on which to sew buttons. The player who gains the most points from their design goal tiles, cats, and buttons wins! COMPONENTS Your game of Calico™ should include the following. If it doesn’t, please email [email protected] 4 Dual-layer Quilt Boards 108 Patch Tiles (6 sets of 18) 2 24 Design Goal Tiles 6 Black + White 5 Double-sided (4 sets of 6 in 4 player colors Patch Tiles Cat Scoring Tiles shown on tile back) 80 Cat Tokens 1 Cloth Tile Bag 1 Score Pad 52 Button Tokens 1 Button Scoring Tile 1 Master Quilter Tile (8 of each color + 4 rainbow) 3 BEGINNER SETUP We recommend using the beginner setup until you are familiar with the game, before moving to the standard setup. A Place the Millie, Tibbit, and Coconut Cat Scoring E Give each player a Quilt Board and their matching set of 6 Tiles and their matching Cat Tokens in the Design Goal Tiles in their player color (your player color is center of the table. Return the other Cat Scoring the stitching color on your Quilt Board). -

Burlington Reports Newsletter, Spring/Summer 2021

Burlington Reports Paws and Claws Society, Inc., Thorofare, NJ Issue 28, Spring/Summer 2021 Partners in Prevention Not Destruction since 1993 What is a Hummingbird Moth? If you’ve seen a creature that resembles the tiniest hummingbird you’ve ever seen, but you aren’t really sure if it’s even a bird at all, you aren't alone. What you’ve seen just might be a hummingbird moth, also called a hawk moth, and it’s actually an insect! Yep, it’s a fascinating insect, and (believe it or - not), some types of hummingbird moths For Fur ther Information . actually begin their lives as those caterpillars You can find more information on our web site at pacsnj.org ! that eat tomato plants, causing grief to gardeners! • Find out What’s New by following links on our home page or clicking “News”. • Read other issues of Burlington Reports by clicking “Newsletter”, or join our email list to be notified when new issues are ready for viewing. Click the link for any issue of the newsletter to comment on that issue’s content. Start or join a discussion! Hover over “Newsletter” on our navigation menu to find “Links for Further Reading” for more information on topics mentioned in Burlington Reports , or click “Share with Squirt” to share a question or story in our Squirty’s Words column. • Hover over “Furry Angels” to learn about pets currently available for adoption, read about pets who have found their Forever Homes, read or submit to the Funny Pages, read “Letters From The Heart”, download forms, and more. -

Cats Are Not Peas Cats Are Not Peas a Calico History of Genetics

Cats Are Not Peas Cats Are Not Peas A Calico History of Genetics Laura Gould A K Peters, Ltd. Wellesley, Massachusetts Editorial, Sales, and Customer Service Office A K Peters, Ltd. 888 Worcester Street, Suite 230 Wellesley, MA 02482 www.akpeters.com Copyright © 2007 by A K Peters, Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. First edition published in 1996 by Copernicus (an imprint of Springer- Verlag New York, Inc.). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gould, Laura L. (Laura Lehmer) Cats are not peas : a calico history of genetics / Laura Gould. – 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-56881-320-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-56881-320-1 (alk. paper) 1. Calico cats. 2. Cats–Genetics. 3. Calico cats–Anecdotes. I. Title. SF449.C34G68 2007 636.8’22–dc22 2007015703 < Cover image: Acknowledgements or statement of location in book> Printed in the United States of America 11 10 09 08 07 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For George, of course (and Max, too) and in memory of my mother, Emma Trotskaya Lehmer, who died peacefully in her Berkeley home exactly halfway through her one hundred and first year, just as the final revisions to this book were being made. She didn’t like cats at all, but she did like Cats Are Not Peas, and was pleased to know that this very personal book would live on.