When Terry Met Miranda: Two Constitutional Doctrines Collide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court of Louisiana

SUPREME COURT OF LOUISIANA No. 97-KK-2551 STATE OF LOUISIANA Versus TIMMIE HILL JOHNSON, J., Dissenting We must strike a balance in this case between the competing interests of a government with the responsibility to maintain safe streets, and the right of persons in America to walk the streets without fear of police action. With this decision, the court has pushed the Terry stop to new levels. Reasonable suspicion that a person may have committed a crime or is about to commit a crime is no longer a requirement for an investigatory stop in Louisiana. See, Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1, 88 S. Ct. 1868 (1968) (holding a police officer may make an investigatory stop when there is reasonable, articulable suspicion to believe that the person has been, is, or is about to be engaged in criminal activity). The majority has concluded that persons in “high crime areas”, which generally means those sections of the community with complaints of narcotics trafficking, can be stopped at will, engaged in conversation, frisked, and have their identity verified. This is an egregious violation of the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution which guarantees that no person shall be subject to an unreasonable search or seizure of their person or property. The majority relies on the multi-factor test set out in Brown v. Illinois, 422 U.S. 590, 603 (1975) to determine whether illegally seized evidence should be suppressed. The majority concedes that the initial Terry stop and frisk, which unearthed no evidence, was illegal. However, they assert that the two outstanding arrest warrants, discovered during the defendant’s unlawful detention, provide an intervening circumstance. -

Probable Cause for Arrest in Indiana: a Prosecutor Hoist with His Own Kinnaird

Indiana Law Journal Volume 45 Issue 1 Article 3 Fall 1969 Probable Cause for Arrest in Indiana: A Prosecutor Hoist With His Own Kinnaird F. Thomas Schornhorst Indiana University Maurer School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Evidence Commons Recommended Citation Schornhorst, F. Thomas (1969) "Probable Cause for Arrest in Indiana: A Prosecutor Hoist With His Own Kinnaird," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 45 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol45/iss1/3 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS PROBABLE CAUSE FOR ARREST IN INDIANA: A PROSECUTOR HOIST WITH HIS OWN KINNAIRD F. THOMAS SCHORNHORSTt For'tis the sport to have the enginer Hoist with his own petar.... HAmtLET, ACT III, SCENE IV A judicial decision that an arrest warrant must be supported by an affidavit alleging facts and circumstances sufficient to justify a magist- rate's finding of probable cause in order to make lawful an arrest and incidental search based on that warrant would not seem worthy of law journal commentary in 1969. One would think that this issue had been settled in the stormy period following Mapp v. Ohio" in Ker v. Cali- fornia,' Beck v. Ohio,' Wong Sun v. United States4 and Aguilar v. -

03-5554 -- Hiibel V. Sixth Judicial Dist. Court of Nev., Humboldt Cty

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2003 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus HIIBEL v. SIXTH JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT OF NEVADA, HUMBOLDT COUNTY, ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF NEVADA No. 03–5554. Argued March 22, 2004—Decided June 21, 2004 Petitioner Hiibel was arrested and convicted in a Nevada court for re- fusing to identify himself to a police officer during an investigative stop involving a reported assault. Nevada’s “stop and identify” stat- ute requires a person detained by an officer under suspicious circum- stances to identify himself. The state intermediate appellate court affirmed, rejecting Hiibel’s argument that the state law’s application to his case violated the Fourth and Fifth Amendments. The Nevada Supreme Court affirmed. Held: Petitioner’s conviction does not violate his Fourth Amendment rights or the Fifth Amendment’s prohibition on self-incrimination. Pp. 3–13. (a) State stop and identify statutes often combine elements of tra- ditional vagrancy laws with provisions intended to regulate police behavior in the course of investigatory stops. They vary from State to State, but all permit an officer to ask or require a suspect to disclose his identity. -

Fourth Amendment--Requiring Probable Cause for Searches and Seizures Under the Plain View Doctrine Elsie Romero

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 78 Article 3 Issue 4 Winter Winter 1988 Fourth Amendment--Requiring Probable Cause for Searches and Seizures under the Plain View Doctrine Elsie Romero Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Elsie Romero, Fourth Amendment--Requiring Probable Cause for Searches and Seizures under the Plain View Doctrine, 78 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 763 (1987-1988) This Supreme Court Review is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/88/7804-763 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAw & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 78, No. 4 Copyright @ 1988 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in U.S.A. FOURTH AMENDMENT-REQUIRING PROBABLE CAUSE FOR SEARCHES AND SEIZURES UNDER THE PLAIN VIEW DOCTRINE Arizona v. Hicks, 107 S. Ct. 1149 (1987). I. INTRODUCTION The fourth amendment to the United States Constitution pro- tects individuals against arbitrary and unreasonable searches and seizures. 1 Fourth amendment protection has repeatedly been found to include a general requirement of a warrant based on probable cause for any search or seizure by a law enforcement agent.2 How- ever, there exist a limited number of "specifically established and -

Fourth Amendment Litigation

Still the American Frontier: Fourth Amendment Litigation Deja Vishny September 2012 United States Constitution: The Fourth Amendment 1 Wisconsin State Constitution Article 1 Sec. 11 The Exclusionary Rule The Fruit of the Poisonous Tree Doctrine Attenuation Inevitable Discovery Independent Source Other exceptions to the Fruit of the Poisonous Tree Doctrine Applicability of the Fourth Amendment: The Expectation of Privacy Cars Sample list of areas the court has found to private and non-private. Deemed Non-Private: Standing & Overnight Guests Searches by Private Parties Requirement of Search Warrant Determination of probable cause Definition of the Home: Curtilage Permissible scope of search warrants Plain View Good Faith Knock and Announce Challenging Search Warrants Permissible warrantless entries and searches in homes and businesses Exception: Search Incident to Arrest Exception: Protective Sweep Exception: Plain View Exception: Exigent Circumstances : The Emergency Doctrine Exception: Exigent Circumstances: Hot Pursuit Exception: Imminent Destruction of Evidence Warrantless searches without entry Consent Searches Who may consent to entry and searches of the home Scope of consent Seizures of Persons: The Terry Doctrine Defining a Seizure Permissible Length of Temporary Seizures Permissible reasons for a Seizure: 2 Seizures bases on anonymous tips Seizures on Public Transportation Requests for Identification Roadblocks: Reasonable Suspicion: Frisk of Suspects Scope of Terry Frisk Seizures of Property Arrest Probable Cause for Arrest Warrantless -

Drawing a Line Between Terry and Miranda: the Degree and Duration of Restraint Katherine M

Drawing a Line between Terry and Miranda: The Degree and Duration of Restraint Katherine M. Swifit INTRODUCTION A felon answered the door in his underwear. Three police officers and three parole officers were there to search his apartment for a gun on the basis of a tip from his mother.! The police handcuffed him in the hallway outside his apartment, but told him he was not under ar- rest; the handcuffs were for his safety and the safety of the officers. Then they took him inside and asked about the gun, which he told them was in a shoebox on the table. The police never read the suspect his Miranda warnings. Was he "in custody"? Or was this merely a tem- porary detention? Mirandav Arizona' held that police may not interrogate a suspect who has been taken into custody without first issuing the familiar warnings Investigative stops, valid under Terry v Ohio,' are not sub- ject to Miranda's notice requirements.! Courts have not settled on a workable rule for determining custody in Terry stop cases. Part of the problem is that custody cases involve so many factors.! But more im- portant, coercive police behavior that would have required Miranda warnings in 1966 often is deemed reasonable under Terry today. This has led to a circuit split over whether coercive Terry stops constitute Miranda custody. The First, Fourth, and Eighth circuits hold t B.A., BJ. 1998, University of Missouri-Columbia; J.D. 2006, The University of Chicago. I The facts used in this example are drawn from United States v Newton, 369 F3d 659, 663 (2d Cir 2004). -

New Haven Department of Police Service General

GENERAL ORDER 5.01 Page 1 of 9 NEW HAVEN DEPARTMENT OF POLICE SERVICE GENERAL ORDERS GENERAL ORDER 5.01 EFFECTIVE DATE: June 6, 2016 5.01.01 PURPOSE The purpose of this General Order is to provide officers of the New Haven Department of Police Service with basic guidelines for conducting arrests. 5.01.02 POLICY It is the policy of the New Haven Department of Police Service that all arrests made by departmental personnel shall be conducted professionally and in accordance with established legal principles. In furtherance of this policy, all officers of this department are expected to be aware of, understand, and follow the laws governing arrest. This policy sets forth the fundamentals of the arrest procedure. 5.01.03 DEFINITIONS ARREST: Actual or constructive seizure or detention of a person, performed with the intention to effect an arrest and so understood by the person detained. ARREST WARRANT: A written order issued by a judge or other proper authority that commands a law enforcement officer to place a person under arrest. GENERAL ORDER &O1 Page 2 of 9 PROBABLE CAUSE FOR ARREST: The existence of circumstances that would lead a reasonably prudent person to believe that a crime was committed and the individual to be arrested has committed the crime. REASONABLE SUSPICION: The existence of circumstances that would lead a reasonable police officer to believe that an individual is engaging in criminal activity. INVESTIGATIVE DETENTION (“TERRY STOP”): Temporary detention for investigative purposes of a person based upon reasonable suspicion that the person has committed, is committing, or is about to commit a crime, under circumstances that do not amount to probable cause for arrest. -

Informer January 2017

Department of Homeland Security Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers Office of Chief Counsel Legal Training Division January 2017 THE FEDERAL LAW ENFORCEMENT -INFORMER- A MONTHLY LEGAL RESOURCE AND COMMENTARY FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS AND AGENTS Welcome to this installment of The Federal Law Enforcement Informer (The Informer). The Legal Training Division of the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers’ Office of Chief Counsel is dedicated to providing law enforcement officers with quality, useful and timely United States Supreme Court and federal Circuit Courts of Appeals reviews, interesting developments in the law, and legal articles written to clarify or highlight various issues. The views expressed in these articles are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers. The Informer is researched and written by members of the Legal Division. All comments, suggestions, or questions regarding The Informer can be directed to the Editor at (912) 267-3429 or [email protected]. You can join The Informer Mailing List, have The Informer delivered directly to you via e-mail, and view copies of the current and past editions and articles in The Quarterly Review and The Informer by visiting https://www.fletc.gov/legal-resources. This edition of The Informer may be cited as 1 INFORMER 17. Join THE INFORMER E-mail Subscription List It’s easy! Click HERE to subscribe, change your e-mail address, or unsubscribe. THIS IS A SECURE SERVICE. No one but the FLETC Legal Division will have access to your address, and you will receive mailings from no one except the FLETC Legal Division. -

Reasonable Suspicion and Mere Hunches

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 59 Issue 2 Article 3 3-2006 Reasonable Suspicion and Mere Hunches Craig S. Lerner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Craig S. Lerner, Reasonable Suspicion and Mere Hunches, 59 Vanderbilt Law Review 407 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol59/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reasonable Suspicion and Mere Hunches Craig S. Lerner 59 Vand. L. Rev. 407 (2006) In Terry v. Ohio, Earl Warren held that police officers could temporarily detain a suspect, provided that they relied upon "specific, reasonable inferences," and not simply upon an "inchoate and unparticularized suspicion or 'hunch."' Since Terry, courts have strained to distinguish "reasonablesuspicion," which is said to arise from the cool analysis of objective and particularized facts, from "mere hunches," which are said to be subjective, generalized, unreasoned and therefore unreliable. Yet this dichotomy between facts and intuitions is built on sand. Emotions and intuitions are not obstacles to reason, but indispensable heuristic devices that allow people to process diffuse, complex information about their environment and make sense of the world. The legal rules governing police conduct are thus premised on a mistaken assumption about human cognition. This Article argues that the legal system can defer, to some extent, to police officers' intuitions without undermining meaningful protections against law enforcement overreaching. -

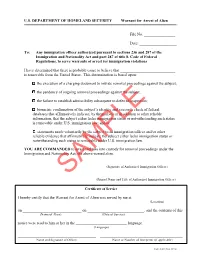

Warrant for Arrest of Alien

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY Warrant for Arrest of Alien File No. ________________ Date: ___________________ To: Any immigration officer authorized pursuant to sections 236 and 287 of the Immigration and Nationality Act and part 287 of title 8, Code of Federal Regulations, to serve warrants of arrest for immigration violations I have determined that there is probable cause to believe that ____________________________ is removable from the United States. This determination is based upon: the execution of a charging document to initiate removal proceedings against the subject; the pendency of ongoing removal proceedings against the subject; the failure to establish admissibility subsequent to deferred inspection; biometric confirmation of the subject’s identity and a records check of federal databases that affirmatively indicate, by themselves or in addition to other reliable information, that the subject either lacks immigration status or notwithstanding such status is removable under U.S. immigration law; and/or statements made voluntarily by the subject to an immigration officer and/or other reliable evidence that affirmatively indicate the subject either lacks immigration status or notwithstanding such status is removable under U.S. immigration law. YOU ARE COMMANDED to arrest and take into custody for removal proceedings under the Immigration and Nationality Act, the above-named alien. __________________________________________ (Signature of Authorized Immigration Officer) __________________________________________ SAMPLE (Printed Name and Title of Authorized Immigration Officer) Certificate of Service I hereby certify that the Warrant for Arrest of Alien was served by me at __________________________ (Location) on ______________________________ on _____________________________, and the contents of this (Name of Alien) (Date of Service) notice were read to him or her in the __________________________ language. -

United States Court of Appeals for the EIGHTH CIRCUIT ______

United States Court of Appeals FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT ___________ No. 05-4275 ___________ United States of America, * * Appellee, * * Appeal from the v. * United States District Court * for the District of Minnesota. Edwin Martinez, Jr., also known as * Edwin Martinez Franco, Jr., * * Appellant. * * ___________ Submitted: June 14, 2006 Filed: September 11, 2006 ___________ Before LOKEN, Chief Judge, BEAM, and ARNOLD, Circuit Judges. ___________ BEAM, Circuit Judge. Edwin Martinez, Jr. appeals his conviction, following a jury verdict, and sentence for bank robbery in violation of 18 U.S.C. sections 2113 (a) and (d). We affirm. Appellate Case: 05-4275 Page: 1 Date Filed: 09/11/2006 Entry ID: 2087747 I. BACKGROUND The Liberty Savings Bank in St. Cloud, Minnesota was robbed on July 23, 2004, at approximately 9:20 a.m. The robber entered the bank, approached a teller, placed a gun on the counter in front of her, and told her this was a robbery. The teller gave the man all the money she had in her drawer. The man pulled his sleeves down over his hands, wiped down the counter with the sleeves, folded the bills in half, and put the wad of bills in one of his pockets. He then slowly backed away, told the teller not to say anything, and left through the front door. The bank contacted the police, and the teller described the robber to them as a black male in his early to mid-twenties, between 5'7" and 5'9" tall, wearing a gray hooded sweatshirt and blue jeans. St. Cloud police officers Michael Lewandowski, Jeff Atkinson, and David Missell responded. -

Fleeting Data: Using Artificial Intelligence to Make Sense of the Border Exception

FLEETING DATA: USING ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE TO MAKE SENSE OF THE BORDER EXCEPTION BRENDAN SULLIVAN* INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 61 I. THE PURPOSE OF THE BORDER EXCEPTION IN A DIGITAL WORLD65 A. How Have Fourth Amendment Rights at the Border Developed? ............................................................................. 67 B. Border Policy .......................................................................... 69 C. Balancing Governmental Interests .......................................... 71 D. What’s Reasonable When it Comes to Technology These Days? ................................................................................................ 72 II. IS A DEVICE SEARCH AS INTRUSIVE AS A STRIP SEARCH? ........... 73 A. Routine and Non-Routine Border Searches ............................ 75 B. Does Technology Make the Search More Intrusive or Less Intrusive? ................................................................................ 76 1. Forensically Intrusive ........................................................ 77 2. Manually Intrusive ............................................................ 77 3. Temporally Intrusive ......................................................... 78 C. When is a Border Search Not a Search Incident to Arrest? .... 79 D. Application to Vessel Searches ............................................... 80 III. HOW CAN CONGRESS PREVENT THREATS WITHOUT BORDER OFFICIALS INTRUDING ON PRIVACY? ..........................................