Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

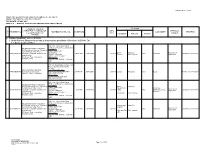

LIST of PROJECTS ISSUED CEASE and DESIST ORDER and CDO LIFTED( 2001-2019) As of May 2019 CDO

HOUSING AND LAND USE REGULATORY BOARD Regional Field Office - Central Visayas Region LIST OF PROJECTS ISSUED CEASE AND DESIST ORDER and CDO LIFTED( 2001-2019) As of May 2019 CDO PROJECT NAME OWNER/DEVELOPER LOCATION DATE REASON FOR CDO CDO LIFTED 1 Failure to comply of the SHC ATHECOR DEVELOPMENT 88 SUMMER BREEZE project under RA 7279 as CORP. Pit-os, Cebu City 21/12/2018 amended by RA 10884 2 . Failure to comply of the SHC 888 ACACIA PROJECT PRIMARY HOMES, INC. project under RA 7279 as Acacia St., Capitol Site, cebu City 21/12/2018 amended by RA 10884 3 A & B Phase III Sps. Glen & Divina Andales Cogon, Bogo, Cebu 3/12/2002 Incomplete development 4 . Failure to comply of the SHC DAMARU PROPERTY ADAMAH HOMES NORTH project under RA 7279 as VENTURES CORP. Jugan, Consolacion, cebu 21/12/2018 amended by RA 10884 5 Adolfo Homes Subdivision Adolfo Villegas San Isidro, Tanjay City, Negros O 7/5/2005 Incomplete development 7 Aduna Beach Villas Aduna Commerial Estate Guinsay, Danao City 6/22/2015 No 20% SHC Corp 8 Agripina Homes Subd. Napoleon De la Torre Guinobotan, Trinidad, Bohol 9/8/2010 Incomplete development 9 . AE INTERNATIONAL Failure to comply of the SHC ALBERLYN WEST BOX HILL CONSTRUCTION AND project under RA 7279 as RESIDENCES DEVELOPMENT amended by RA 10884 CORPORATION Mohon, Talisay City 21/12/2018 10 Almiya Subd Aboitizland, Inc Canduman, Mandaue City 2/10/2015 No CR/LS of SHC/No BL Approved plans 11 Anami Homes Subd (EH) Softouch Property Dev Basak, Lapu-Lapu City 04/05/19 Incomplete dev 12 Anami Homes Subd (SH) Softouch Property -

PESO-Region 7

REGION VII – PUBLIC EMPLOYMENT SERVICE OFFICES PROVINCE PESO Office Classification Address Contact number Fax number E-mail address PESO Manager Local Chief Executive Provincial Capitol , (032)2535710/2556 [email protected]/mathe Cebu Province Provincial Cebu 235 2548842 [email protected] Mathea M. Baguia Hon. Gwendolyn Garcia Municipal Hall, Alcantara, (032)4735587/4735 Alcantara Municipality Cebu 664 (032)4739199 Teresita Dinolan Hon. Prudencio Barino, Jr. Municipal Hall, (032)4839183/4839 Ferdinand Edward Alcoy Municipality Alcoy, Cebu 184 4839183 [email protected] Mercado Hon. Nicomedes A. de los Santos Municipal Alegria Municipality Hall, Alegria, Cebu (032)4768125 Rey E. Peque Hon. Emelita Guisadio Municipal Hall, Aloquinsan, (032)4699034 Aloquinsan Municipality Cebu loc.18 (032)4699034 loc.18 Nacianzino A.Manigos Hon. Augustus CeasarMoreno Municipal (032)3677111/3677 (032)3677430 / Argao Municipality Hall, Argao, Cebu 430 4858011 [email protected] Geymar N. Pamat Hon. Edsel L. Galeos Municipal Hall, (032)4649042/4649 Asturias Municipality Asturias, Cebu 172 loc 104 [email protected] Mustiola B. Aventuna Hon. Allan L. Adlawan Municipal (032)4759118/4755 [email protected] Badian Municipality Hall, Badian, Cebu 533 4759118 m Anecita A. Bruce Hon. Robburt Librando Municipal Hall, Balamban, (032)4650315/9278 Balamban Municipality Cebu 127782 (032)3332190 / Merlita P. Milan Hon. Ace Stefan V.Binghay Municipal Hall, Bantayan, melitanegapatan@yahoo. Bantayan Municipality Cebu (032)3525247 3525190 / 4609028 com Melita Negapatan Hon. Ian Escario Municipal (032)4709007/ Barili Municipality Hall, Barili, Cebu 4709008 loc. 130 4709006 [email protected] Wilijado Carreon Hon. Teresito P. Mariñas (032)2512016/2512 City Hall, Bogo, 001/ Bogo City City Cebu 906464033 [email protected] Elvira Cueva Hon. -

Item Indicators Amlan Ayungon Bacong Bais (City) Basay Bayawan (City) Bindoy Dauin Dumaguete (City)Guihulngan (City) Jimalalud L

Item Indicators Amlan Ayungon Bacong Bais (city) Basay Bayawan (city) Bindoy Dauin Dumaguete (city)Guihulngan (city) Jimalalud Libertad Manjuyod San Jose Santa Catalina Siaton Sibulan Tanjay (city) Tayasan Vallenermoso Zamboanguita 1.1 M/C Fisheries Ordinance Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes 1.2 Ordinance on MCS Yes Yes Yes No No Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No No Yes Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes 1.3a Allow Entry of CFV No N/A No No Yes No Yes No No No No No No Yes No Yes No No No No Yes 1.3b Existence of Ordinance No No No No No No Yes No No N/A No No Yes No No No No No No Yes 1.4a CRM Plan Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes 1.4b ICM Plan Yes No No No No No No No No No Yes No Yes No Yes No N/A Yes No No 1.4c CWUP No No No No No No No No No No Yes No Yes No Yes No N/A Yes No No 1.5 Water Delineation Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes Yes No No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes No Yes 1.6a Registration of fisherfolk Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.6b List of org/coop/NGOs Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.7a Registration of Boats Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 1.7b Licensing of Boats Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes Yes No No N/A Yes No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes Yes 1.7c Fees for Use of Boats Yes Yes No No No Yes No Yes No No No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes 1.8a Licensing of Gears Yes No No No No Yes Yes Yes No -

A. MINING TENEMENT APPLICATIONS 1. Under Process (Returned Pursuant to the Pertinent Provisions of Section 4 of EO No

ANNEX B Page 1 of 105 MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU REGIONAL OFFICE NO. VII MINING TENEMENTS STATISTICS REPORT FOR MONTH OF MAY, 2017 ANNEX B - MINERAL PRODUCTION SHARING AGREEMENT (MPSA) TENEMENT HOLDER/ LOCATION line PRESIDENT/ CHAIRMAN OF AREA PREVIOUS TENEMENT NO. ADDRESS/FAX/TEL. NO. DATE FILED COMMODITY REMARKS no. THE BOARD/CONTACT (has.) Barangay/s Mun./City Province HOLDER PERSON A. MINING TENEMENT APPLICATIONS 1. Under Process (Returned pursuant to the pertinent provisions of Section 4 of EO No. 79) 1.1. By the Regional Office 25th Floor, Petron Mega Plaza 358 Sen. Gil Puyat Ave., Makati City Apo Land and Quarry Corporation Cebu Office: Mr. Paul Vincent Arcenas - President Tinaan, Naga, Cebu Contact Person: Atty. Elvira C. Contact Nos.: Bairan Naga City Apo Cement 1 APSA000011VII Oquendo - Corporate Secretary and 06/03/1991 10/02/2009 240.0116 Cebu Limestone Returned on 03/31/2016 (032)273-3300 to 09 Tananas San Fernando Corporation Legal Director FAX No. - (032)273-9372 Mr. Gery L. Rota - Operations Manila Office: Manager (Cebu) (632)849-3754; FAX No. - (632)849- 3580 6th Floor, Quad Alpha Centrum, 125 Pioneer St., Mandaluyong City Tel. Nos. Atlas Consolidated Mining & Cebu Office (Mine Site): 2 APSA000013VII Development Corporation (032) 325-2215/(032) 467-1408 06/14/1991 01/11/2008 287.6172 Camp-8 Minglanilla Cebu Basalt Returned on 03/31/2016 Alfredo C. Ramos - President FAX - (032) 467-1288 Manila Office: (02)635-2387/(02)635-4495 FAX - (02) 635-4495 25th Floor, Petron Mega Plaza 358 Sen. Gil Puyat Ave., Makati City Apo Land and Quarry Corporation Cebu Office: Mr. -

Foreclosurephilippines.Com6 the Bid Offer Shall Not Be Lower Than the Minimum Bid Set by the Fund

LOANS MANAGEMENT AND RECOVERY DEPARTMENT Cebu Housing Hub Pag-IBIG FUND / WT Corporate Tower Cebu Business Park, Cebu City INVITATION TO BID April 24, 2018 The Pag-IBIG Fund Committee on Disposition of Acquired Assets shall conduct a sealed public auction for the sale of acquired asset properties on: DATE VENUE AREAS NO. OF UNITS AMLAN AND BAIS CITY 16 Mcdonald's Main-Dumaguete City, Function Area 1, Priscilla M. Tan BACONG, DUMAGUETE AND SIBULAN 21 April 24, 2018 Bldg., Cor. Gov. Perdices & Bishop Epifanio B. Surban St., Dumaguete City (Fronting Quezon Park and Unitop). CANLAON AND GUIHULNGAN 13 PAMPLONA 1 TOTAL 51 GENERAL GUIDELINES 1 Interested parties are required to secure copies of: (a) INSTRUCTION TO BIDDERS (HQP-AAF-104) and (b) OFFER TO BID (HQP-AAF-103) from the office of the Loans Management and Recovery Department – Acquired Asset Management at 3rd floor, Pag-IBIG FUND – WT Corporate Tower, Mindanao Avenue, Cebu Business Park, Cebu City or Pag-IBIG Fund Dumaguete MSB Office, Manuel L. Teves St., Taclobo, Dumaguete City or may download the forms at www.pagibigfund.gov.ph (link Disposition of Acquired Assets for Public Auction). 2 Properties shall be sold on an “AS IS, WHERE IS” basis. 3 All interested buyers are encouraged to inspect the property/ies before tendering their offer/s. The list of the properties may be viewed at www.pagibigfund.gov.ph/aa/aa.aspx (Other properties for sale – Disposition of Acquired Assets for Public Auction). 4 Bidders are also encouraged to visit our website, www.pagibigfund.gov.ph/aa/aa.aspx five (5) days prior the actual auction date, to check whether there are any erratum posted on the list of properties posted under the sealed public auction. -

Regional Health Research and Development Priorities in Central Visayas

REGIONAL HEALTH RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT PRIORITIES IN CENTRAL VISAYAS CRISOL J. TABAREJO, M.D., MSEpi(PH) Regional Research Coordinator Center for Health Development VII 1 Table of Contents I. Regional Profile 3 A. Composition 3 B. Geography 3 C. Population 3 D. Health Status 4 E. Health Manpower 8 F. Health Facilities 8 II. Regional Status 9 III. Methodology 11 IV. Research Priority Areas 12 V. Annexes 26 2 REGIONAL PROFILE 2004 Composition Region VII is commonly known as Central Visayas. It is composed of four (4) provinces, namely: Bohol, Cebu, Negros Oriental and Siquijor. Strategically scattered over these provinces are the cities of Cebu, Danao, Lapu-lapu, Mandaue, Talisay and Toledo in Cebu Province; Bais, Bayawan, Canlaon, Tanjay and Dumaguete in Negros Oriental, and Tagbilaran in Bohol. Central Visayas consists of one hundred twenty (120) municipalities and two thousand, nine hundred sixty-four (2,964) barangays distributed as follows: a. CEBU - forty-seven (47) municipalities and one thousand one hundred seventy-two (1,172) barangays; b. BOHOL - forty-seven (47) municipalities and one thousand one hundred three (1,103) barangays; c. NEGROS ORIENTAL - twenty (20) municipalities and five hundred fifty-five (555) barangays; and d. SIQUIJOR - six (6) municipalities and one hundred thirty-four (134) barangays. Geography Region VII is located in the central part of the Philippine archipelago. Its geographic boundaries are the Visayan Sea in the north and Mindanao Sea in the south. The island of Leyte defines its eastern borders and Negros Occidental marks its western limits. The whole region occupies a total land area of 1,492,310 hectares which is approximately 6% of the total land area of the entire Philippines. -

Today in the History of Cebu

Today in the History of Cebu Today in the History of Cebu is a record of events that happened in Cebu A research done by Dr. Resil Mojares the founding director of the Cebuano Studies Center JANUARY 1 1571 Miguel Lopez de Legazpi establishing in Cebu the first Spanish City in the Philippines. He appoints the officials of the city and names it Ciudad del Santisimo Nombre de Jesus. 1835 Establishment of the parish of Catmon, Cebu with Recollect Bernardo Ybañez as its first parish priest. 1894 Birth in Cebu of Manuel C. Briones, publisher, judge, Congressman, and Philippine Senator 1902 By virtue of Public Act No. 322, civil government is re established in Cebu by the American authorities. Apperance of the first issue of Ang Camatuoran, an early Cebu newspaper published by the Catholic Church. 1956 Sergio Osmeña, Jr., assumes the Cebu City mayorship, succeeding Pedro B. Clavano. He remains in this post until Sept.12,1957 1960 Carlos J. Cuizon becomes Acting Mayor of Cebu, succeeding Ramon Duterte. Cuizon remains mayor until Sept.18, 1963 . JANUARY 2 1917 Madridejos is separated from the town of Bantayan and becomes a separate municipality. Vicente Bacolod is its first municipal president. 1968 Eulogio E. Borres assumes the Cebu City mayorship, succeeding Carlos J. Cuizon. JANUARY 3 1942 The “Japanese Military Administration” is established in the Philippines for the purpose of supervising the political, economic, and cultural affairs of the country. The Visayas (with Cebu) was constituted as a separate district under the JMA. JANUARY 4 1641 Volcanoes in Visayas and Mindanao erupt simultaneously causing much damage in the region. -

Natural Resources 51

50 CHAPTER 4 NATURAL RESOURCES 51 Chapter 4 NATURAL RESOURCES his chapter provides background information on the status of the mineral resources, forest resources, and coastal resources in the profile area, which t help determine the best resource use and approach to resource management. MINERAL RESOURCES The province of Negros Oriental has a variety of mineral resources of important economic value with copper topping the list. In the profile area, minor deposits of copper are found in the Manjuyod, Sibulan, Bacong, and Dauin area (OPA 1990). Iron and its related compounds of magnetite, pyrite, and marcasite are also found in Sibulan. Solar salt is made in Tanjay, Bais City, and Manjuyod. Other deposits include limestone, dolomite, diatomite, manganese, galena, gypsum, phosphate, and china clay (OPA 1990). Commercial deposits of red burning clay are mostly found in the southeastern portion of Negros Oriental; however, some deposits are spread throughout the profile area. Sand and gravel is also extracted from municipalities in the province and in the profile area. A total of 103,000 m3 of sand and gravel has been extracted in recent years (PPDO 1999). UPLAND FOREST RESOURCES Total good forestland in the province of Negros Oriental is believed to be only 5 percent (27,011 ha) of the total land area of the province (540,230 ha). This low forest cover is due to illegal logging activities that are difficult to stop despite government efforts to formulate laws and enforce prohibition. According to PPDO (1992), forestland is 281,386 ha and is broken down into 5 categories. The categories and the respective areas are summarized in Table 4.1. -

Science Performance Predictors of the First Batch of the K-12 Curriculum in Valencia District, Negros Oriental, Philippines Craig N

Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences Volume 15, Issue 4, (2020) 777-819 www.cjes.eu Science performance predictors of the first batch of the K-12 curriculum in Valencia District, Negros Oriental, Philippines Craig N. Refugio*, Negros Oriental State University, College of Education, Graduate School, Math Department & College of Engineering & Architecture, Negros, Dumaguete City 6200, Philippines. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1374-6103 Joel T. Genel, Negros Oriental State University, Negros Oriental Schools Division, Dumaguete City, 6200, Philippines Liza J. Caballero, Negros Oriental State University, College of Education & Graduate School, Bayawan-Sta Catalina Campus, Bayawan City 6221, Philippines Dundee G. Colina, Negros Oriental State University, College of Arts & Sciences, Foundation University, Dumaguete City 6200, Philippines. Kristine N. Busmion, Silliman University, Basic Education Department, Dumaguete City 6200, Philippines. Roger S. Malahay, Negros Oriental state University, College of Arts & Sciences, Guihulngan Campus, Guihulngan, 6214 Philippines Suggested Citation: Refugio, C.N., Genel, J.T., Caballero, L. J., Colina, D.G., Busmion, K.N., Malahay, R.S., (2020). Science performance predictors of the first batch of the K-12 curriculum in Valencia District, Negros Oriental, Philippines. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences. 15(3), 777-819. DOI: 10.18844/cjes.v%vi%i.4590 Received from October 13, 2019; revised from February 15, 2020; accepted from June 24, 2020. Selection and peer review under responsibility of Prof. Dr. Huseyin Uzunboylu, Higher Education Planning, Supervision, Accreditation and Coordination Board, Cyprus. ©2020 Birlesik Dunya Yenilik Arastirma ve Yayincilik Merkezi. All rights reserved.. Abstract The authors designed and conducted this study using the predictive analytics to determine the different science performance predictors of the first batch of K to 12 curriculum in Valencia District, Valencia, Negros Oriental. -

3 2Aef: Lr: I :L

Republic of the Philippines Department of Education Region Vll, Central Visayas " REOTON V + SCHOOLS DIVISION OF DUMAGUETE CITY Dumaguete City (;dNTRor= 1 fi, t '-- uary 13, 2020 r,'.1F.' Jllaf "" JAN I 3 2AeF: lr: I :l DIVISION MEMORAN N', o2r , s. ZDzo MEDIA AND INFORMATION TITERACY TRAINING.WORKSHOP To: Asst. Schools Division Superintendent Chief, Curriculum lmplementation Division Education Program Supervisors School Heads of Public Senior High Schools All Others Concerned 1. Attached is a letter from MADEUNE B. QUIAMCO, ph.D., Dean of the College of Mass communication of silliman University, inviting senior High schools to send their Media and Information Literacy teachers to the two-day training-workshop on January 30-31, 2020 at Silliman University. 2. Each Senior High School is directed to send two (2) participants, the Media and lnformation Literacy teacher and the lcr teacher. please advise the participants to accomplish the attached Confirmation Form on or before January 20, ZOZO 3 For more details, please refer to the attached enclosures. 4 Wide dissemination of this Memorandum is desired. GREGORIO CYRUS R, ORDE, Ed. D., CESO V Schools Divisi Superintendent ( COLLECE OF MASS COMMUNICATION 6*--). i F{'"1r,1i SILLIMAN UN IVERS ITY \T*;i,#: Euildins CoitPct cncc, Ch ardctcr tJ Foith i January 8, 2019 i r.- if!. SrDq 1 Jry' Dr. Gregorio Cyrus R. Elejorde, CESO V Schools Division Superintendent, Dumaguete City Taclobo, Dumaguete City, Negros Oriental du maguete.city@ dePed.gov. Ph Dear Dr. Elejorde, (AUC) Silliman University and the Asian lnstitute of Journalism and Communication are and conducting a train ing-workshop for a select group of senior High school teachers in Media lnformation Literacy (MlL) on 30-31 January 2020. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BOHOL 1,255,128 ALBURQUERQUE 9,921 Bahi 787 Basacdacu 759 Cantiguib 5

2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BOHOL 1,255,128 ALBURQUERQUE 9,921 Bahi 787 Basacdacu 759 Cantiguib 555 Dangay 798 East Poblacion 1,829 Ponong 1,121 San Agustin 526 Santa Filomena 911 Tagbuane 888 Toril 706 West Poblacion 1,041 ALICIA 22,285 Cabatang 675 Cagongcagong 423 Cambaol 1,087 Cayacay 1,713 Del Monte 806 Katipunan 2,230 La Hacienda 3,710 Mahayag 687 Napo 1,255 Pagahat 586 Poblacion (Calingganay) 4,064 Progreso 1,019 Putlongcam 1,578 Sudlon (Omhor) 648 Untaga 1,804 ANDA 16,909 Almaria 392 Bacong 2,289 Badiang 1,277 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Buenasuerte 398 Candabong 2,297 Casica 406 Katipunan 503 Linawan 987 Lundag 1,029 Poblacion 1,295 Santa Cruz 1,123 Suba 1,125 Talisay 1,048 Tanod 487 Tawid 825 Virgen 1,428 ANTEQUERA 14,481 Angilan 1,012 Bantolinao 1,226 Bicahan 783 Bitaugan 591 Bungahan 744 Canlaas 736 Cansibuan 512 Can-omay 721 Celing 671 Danao 453 Danicop 576 Mag-aso 434 Poblacion 1,332 Quinapon-an 278 Santo Rosario 475 Tabuan 584 Tagubaas 386 Tupas 935 Ubojan 529 Viga 614 Villa Aurora (Canoc-oc) 889 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and -

Fisheries Profile of Negros Oriental Province

Fisheries Profile of Negros Oriental Province Negros Oriental occupies the south-eastern half of the island of Negros, with Negros Occidental comprising the north-western half. It has a total land area of 5,385.53 square kilometres (2,079.36 sq mi). [11] A chain of rugged mountains separates Negros Oriental from Negros Occidental. Negros Oriental faces Cebu to the east across the Tañon Strait and Siquijor to the southeast. The Sulu Sea borders it to the south to southwest. The population of Negros Oriental in the 2015 census was 1,354,995 people,[2] with a density of 250 inhabitants per square kilometre or 650 inhabitants per square mile. Its registered voting population are 606,634.[19] 34.5% of the population are concentrated in the six most populous component LGUs of Dumaguete City, Bayawan City, Guihulngan City, Tanjay City, Bais City and Canlaon City. Population growth per year is about 0.99% over the period 2010-2015, lower than the national average of 1.72%.[2] Residents of Negros are called "Negrenses" (and less often "Negrosanons") and many are of either pure/mixedAustronesian heritage, with foreign ancestry as minorities. Negros Oriental is predominantly a Cebuano-speaking province by 77%, due to its close proximity to Cebu. Hiligaynon/Ilonggo is spoken by the remaining 23% and is common in areas close to the border with Negros Occidental. Filipino and English, though seldom used, are generally understood and used for official, literary and educational purposes. Population census of Negros Oriental Year Pop. ±% p.a. 1990 925,272 — 1995 1,025,247 +1.94% 2000 1,130,088 +2.11% 2007 1,231,904 +1.20% 2010 1,286,666 +1.60% 2015 1,354,995 +0.99% Source: Philippine Statistics Authority [2][16][16] Negros Oriental comprises 19 municipalities and 6 cities, further subdivided into 557 barangays.