P'. RS Moorey, MA, Dphil, FBA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benjamin FM Final.Indd

PREVIEW: INTRODUCTION • The Task of Introductions • Types of Introductions: Organized around • Archaeological Calendar • The Canon of the Bible • Daily Life • Archaeological Sites • Travel • History of Archaeology • Popular Interest • Organization of This Introduction • Popular Archaeology • Cultural History • Annales Archaeology • Processual Archaeology • Post-Processual Archaeology Introduction THE TASK OF INTRODUCTIONS TO the world of the Bible—and about the Bible itself. ARCHAEOLOGY AND THE BIBLE Together archaeology and the Bible unlock the most profound responses to the challenges that Th e three Rs of archaeology are to recover, to confront humans who want not only to make a read, and to reconstruct the cultural property living but also to make a diff erence in the world of now-extinct cultures (Magness 2002, 4–13; that is their home. Darvill 2002). Archaeologists listen to the sto- ries that stones—like architecture, art, pottery, Archaeology is the recovery, jewelry, weapons, and tools—have to tell. Stones interpretation, and reconstruction of and Stories: An Introduction to Archaeology and the cultural property of now-extinct the Bible describes how archaeologists listen, what cultures. they are hearing, and what a diff erence it makes for understanding the Bible. Archaeology is not the plunder of the trea- Archaeology in the world of the Bible does sures of ancient cultures, nor proving that the not prove the Bible wrong, any more than biblical Bible’s descriptions of people and events are his- archaeology proves the Bible right. Archaeology torically accurate, nor a legal remedy for deter- off ers new ways of defi ning the Bible in relation mining which people today have a legal right to to its own world, and of using it more eff ectively the land. -

Oriental Institute Staff Newsletter January 2005

OI NEWSLETTER - SECOND MONDAY - JANUARY 2005 FROM THE EDITOR THE DIRECTOR'S OFFICE UNITS COMPUTER LAB / John Sanders DEVELOMENT / Monica Witczak MUSEUM / Geoff Emberling MUSEUM EDUCATION / Wendy Ennes PUBLICATIONS (Department Head Report) / Thomas A. Holland RESEARCH ARCHIVES / Chuck Jones WEBSITE / Chuck Jones - John Sanders PROJECTS EPIGRAPHIC SURVEY / Ray Johnson INDIVIDUALS GENE GRAGG WALTER KAEGI IN THE NEWS +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+ FROM THE EDITOR +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+ The OI Newsletter appears by way of the automated mailing list: https://listhost.uchicago.edu/mailman/listinfo/oi-newsletter The archive of all issues of the newsletter dating back to early 1998 is accessible only to members of the list. If you wish to have access to the archive, please request your password from: [email protected] Please send any other inquiries about the newsletter to the same address. +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+ THE DIRECTOR'S OFFICE +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+ Hoping Everyone had a Happy Holiday The month of December was a short work period for many at the OI. We hope you all had a wonderful holiday break and were able to spend time with family and friends. We know that any time off in December will be repaid in full in January as activities and events pick up. Special thanks to all of you who worked over the holidays, especially students who filled in. Also, special thanks to staff in security functions, education programs and the Suq which all remain open for much of the holidays so visitors can enjoy the museum. Thanks to everyone involved and we hope that you were able to free up alternative time to recharge. Faculty Award Congratulations to Tony Brinkman who has received the Mellon Emeritus Fellowship. -

The HIGHLIGHTS of the ANNUAL REPORT 2002-03

Ashmolean AR cover update 8/3/04 5:12 pm Page 2 AshmoleanThe HIGHLIGHTS OF THE ANNUAL REPORT 2002-03 AshmoleanThe OXFORD OX1 2PH For information phone: 01865-278000 Ashmolean Annual Report 2003c 10/3/04 12:04 pm Page 2 The Museum is open from Tuesday to Saturday throughout the year from 10am to 5pm, on Sundays from 2pm to 5pm and until 7.30pm on Thursdays during the summer months. A fuller version of the Ashmolean’s Annual Report, including the Director’s Report and complete Departmental and Staff records is available by post from The Publications Department, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford OX1 2PH. To order, telephone 01865 278010 Or it can be viewed on the Museum’s web site: http://www.ashmol.ox.ac.uk/annualreport It may be necessary to install Acrobat Reader to access the Annual Report. There is a link on the web site to facilitate the down-loading of this program. Ashmolean Annual Report 2003c 10/3/04 12:05 pm Page 1 University of Oxford AshmoleanThe Museum HIGHLIGHTS OF THE Annual Report 2002-2003 Ashmolean Annual Report 2003c 10/3/04 12:05 pm Page 2 VISITORS OF THE ASHMOLEAN MUSEUM as at 31 July 2003 Nicholas Barber (Chairman) The Vice-Chancellor (Sir Colin Lucas) The Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Academic Services and University Collections) (Prof. Paul Slack) The Junior Proctor (Dr Ian Archer) Professor Alan K Bowman The Rt Hon The Lord Butler of Brockwell Professor Barry W Cunliffe James Fenton The Lady Heseltine Professor Martin J Kemp Professor Paul Langford The Rt Hon The Lord Rothschild, GBE The Rt Hon The Lord Sainsbury of Preston Candover, KG The Rt Hon Sir Timothy Sainsbury Cover Illustration: Pair of six-fold screens: Tigers (detail) by Kishi Ganku (1749-1828) Editor: Sarah Brown Designed and set by Baseline Arts Ltd, Oxford. -

Arabia and the Arabs

ARABIA AND THE ARABS Long before Muhammad preached the religion of Islam, the inhabitants of his native Arabia had played an important role in world history as both merchants and warriors. Arabia and the Arabs provides the only up-to-date, one-volume survey of the region and its peoples from prehistory to the coming of Islam. Using a wide range of sources – inscriptions, poetry, histories and archaeological evidence – Robert Hoyland explores the main cultural areas of Arabia, from ancient Sheba in the south to the deserts and oases of the north. He then examines the major themes of: •the economy • society •religion •art, architecture and artefacts •language and literature •Arabhood and Arabisation. The volume is illustrated with more than fifty photographs, drawings and maps. Robert G. Hoyland has been a research fellow of St John’s College, Oxford since 1994. He is the author of Seeing Islam As Others Saw It and several articles on the history of the Middle East. He regularly conducts fieldwork in the region. ARABIA AND THE ARABS From the Bronze Age to the coming of Islam Robert G. Hoyland London and New York First published 2001 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. © 2001 Robert G. Hoyland All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Puabi's Adornment for the Afterlife: Materials And

PUABI’S ADORNMENT FOR THE AFTERLIFE: MATERIALS AND TECHNOLOGIES OF JEWELRY AT UR IN MESOPOTAMIA KIM BENZEL Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 ©2013 Kim Benzel All rights reserved ABSTRACT PUABI’S ADORNMENT FOR THE AFTERLIFE: MATERIALS AND TECHNOLOGIES OF JEWELRY AT UR IN MESOPOTAMIA KIM BENZEL This dissertation investigates one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the 20th century – the jewelry belonging to a female named Pu-abi buried in the so-called Royal Cemetery at the site of Ur in southern Mesopotamia, modern Iraq. The mid-third millennium B.C. assemblage represents one of the earliest and richest extant collections of gold and precious stones from antiquity and figures as one of the most renowned and often illustrated aspects of Sumerian culture. With a few notable exceptions most scholars have interpreted these jewels primarily as a reflection in burial of a significant level of power and prestige among the ruling kings and queens of Ur at the time. While the jewelry certainly could, and undoubtedly did, reflect the identity and status of the deceased, I believe that it might have acted as much more than a mere marker and that the identity and status thus signaled might have had a considerably more nuanced meaning, or even a different one, than that of royalty or royalty alone. Based on a thorough examination of the materials and methods used to manufacture these ornaments, I will argue that the jewelry was not simply a rich but passive collection of prestige goods, rather that jewelry that can be read in terms of active ritual, and perhaps cultic, production and display. -

Peter Roger Stuart Moorey 1937–2004

PETER ROGER STUART MOOREY Peter Roger Stuart Moorey 1937–2004 ROGER MOOREY WAS ONE OF THOSE RARE SCHOLARS who was equally at home in the archaeology of Mesopotamia, Iran or the Levant, and he had more than a passing interest in Egypt. He was truly a scholar of the whole of the Ancient Near East, and attempts to circumscribe him more nar- rowly, and suggest that he was more interested in one region than in another, are misguided. For the whole of his professional life he worked in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, and it was as a museum curator that he really made his mark and established a new benchmark for the profession. Early life (Peter) Roger (Stuart) Moorey was born on 30 May 1937 at 64 Hazelwood Road, Bush Hill Park, Enfield, Middlesex. His father, Stuart Moorey (known as Sam), was born in Ripon, Yorkshire, in 1906. He was educated at Ripon Grammar School and Selwyn College, Cambridge, where he was captain of the college rugby XV. He became Senior Master of Tottenham Grammar School, where he taught history and rugby. Roger’s mother, Freda Delanoy Harris, was born in Newark, Nottinghamshire, in 1909. Roger had one younger sister, Janet, who was born in 1939. Sadly, Roger’s mother passed away in 1947, when he was just nine years old. His father married again, and had a daughter with his second wife, but tragically he died shortly thereafter, in 1951, aged forty-four, whilst refereeing a Tottenham Grammar School rugby match. At this time the family was living at 46 Grovelands Road, Palmers Green, London. -

NEWSLETTER NO. 15 May 2005

BRITISH SCHOOL OF ARCHAEOLOGY IN IRAQ NEWSLETTER NO. 15 May 2005 BRITISH SCHOOL OF ARCHAEOLOGY IN IRAQ (GERTRUDE BELL MEMORIAL) REGISTERED CHARITY NO. 219948 BRITISH SCHOOL OF ARCHAEOLOGY IN IRAQ 10, CARLTON HOUSE TERRACE LONDON SW1Y 5AH E-mail: [email protected] Web-site http://www.britac.ac.uk/institutes/iraq/ The next BSAI Newsletter will be published in November 2005 and brief contributions are welcomed on recent research, publications and events. All contributions should be sent to the British School of Archaeology in Iraq, 10 Carlton House Terrace, London SW1Y 5AH, United Kingdom or via e-mail to: [email protected] or fax 44+(0)20 7969 5401 to arrive by October 15, 2005. Joan Porter MacIver edits the BSAI Newsletter. BSAI RESEARCH GRANTS The School considers applications for individual research and travel grants twice a year, in spring and autumn, and all applications must be received by 15th April or 15th October in any given year. Grants are available to support research into the archaeology, history or languages of Iraq and neighbouring countries, and the Gulf, from the earliest times. Awards will normally fall within a limit of £1,000, though more substantial awards may be made in exceptional cases. Grantees will be required to provide a written report of their work, and abstracts from grantee’s reports will be published in future issues of the BSAI Newsletter (published May & November). Grantees must provide a statement of accounts with supporting documents/receipts, as soon as possible and in any case within six months of the work for which the grant was awarded being completed. -

Ashmolean Museum Annual Report 2000—2001

1 UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD ASHMOLEAN MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2000—2001 DEPARTMENTAL AND STAFF RECORDS Accessions, loans, exhibitions, conversation, documentation, Education, publications and other related activities 2 CONTENTS Department of Antiquities ................................................................................... 3 Department of Western Art ................................................................................. 9 The Hope Collection ......................................................................................... 21 Department of Eastern Art ................................................................................ 22 Heberden Coin Room ........................................................................................ 27 The Cast Gallery ................................................................................................. 31 The Beazley Archive ........................................................................................... 34 Conservation Department.................................................................................. 36 Friends of the Ashmolean Museum .................................................................. 43 Publications ......................................................................................................... 44 Education Service ............................................................................................... 46 Administration Department.............................................................................. -

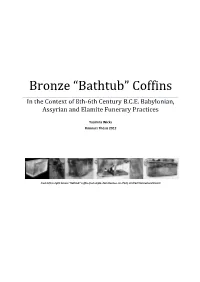

“Bathtub” Coffins in the Context of 8Th-6Th Century B.C.E

Bronze “Bathtub” Coffins In the Context of 8th-6th Century B.C.E. Babylonian, Assyrian and Elamite Funerary Practices Yasmina Wicks Honours Thesis 2012 From left to right: bronze “bathtub” coffins from Arjān, Rām Hormuz, Ur (PG1), Ur (PG2) Nimrud and Zincirli Abstract Central to this thesis are a small number of unique bronze “bathtub” coffins found in 8th–6th century B.C.E. Babylonian, Assyrian and Elamite burial contexts. These fascinating burial containers have not previously been subject to an in-depth analysis, but rather have been treated by archaeologists as little more than convenient receptacles for a body and numerous precious objects deemed more worthy of scholarly interest. This thesis takes the opportunity to narrow this gap in scholarship, by firstly drawing together the available evidence for the excavated coffins, investigating the method and place of their manufacture, and establishing a possible date range for their production and use. Then, to progress towards an understanding of the bronze “bathtub” coffin burials within the broader context of regional funerary practices, they are incorporated into an analysis of Neo-Babylonian, Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Elamite mortuary evidence, with a particular focus on burial typology, grave goods and burial location. The use of the bronze “bathtubs” as burial receptacles also demands that they be viewed in light of Mesopotamian and Elamite beliefs about what happens to people upon their death, and what the funerary ritual should involve. This thesis therefore explores the coffins in the context of these beliefs and then, building upon this analysis, considers possible ideological aspects of the coffins with emphasis on motifs, form and material, and why these may have been appropriate in a burial context. -

Ashmolean Museum Annual Report 2001—2002

ii / 1 UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD ASHMOLEAN MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT 2001—2002 DEPARTMENTAL AND STAFF RECORDS Accessions, loans, exhibitions, conservation, documentation, education, publications and other related activities ii / 2 CONTENTS Department of Antiquities ................................................................................... 3 Department of Western Art ............................................................................... 11 The Hope Collection ......................................................................................... 22 Department of Eastern Art ................................................................................ 23 Heberden Coin Room ........................................................................................ 28 The Cast Gallery ................................................................................................. 32 The Beazley Archive ........................................................................................... 35 Conservation Department.................................................................................. 37 Friends of the Ashmolean Museum .................................................................. 41 Publications ......................................................................................................... 42 Education Service ............................................................................................... 45 Administration Department.............................................................................. -

Asia and the Middle East

World Archaeology at the Pitt Rivers Museum: A Characterization edited by Dan Hicks and Alice Stevenson, Archaeopress 2013, page 455-470 21 Asia and the Middle East Dan Hicks 21.1 Introduction The Pitt Rivers Museum (PRM) holds c. 14,624 objects from Asia that are currently defined as ‘archaeological’ Table( 1.6). The largest collections within this Asian material are represented by the c. 5,449 artefacts from India, the c. 3,524 artefacts from Israel, the c. 1,602 artefacts from Sri Lanka, the c. 1,099 artefacts from Jordan, the c. 510 artefacts from Japan, and the c. 363 artefacts from the Occupied Palestinian Territories. These collections are explored over the next five chapters (Chapters 22– 26), and are introduced in this chapter. The material from the Middle East is considered first (21.2 below). A brief overview of the c. 3,524 objects from the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Israel and Jordan is provided in section 21.2.1, before a full account of them is set out in Chapter 22. The subsequent sections outline the c. 323 objects from Iraq (21.2.2), the c. 227 objects from Saudi Arabia (21.2.3), the c. 132 objects from Syria (21.2.4), the c. 92 objects from Lebanon (21.2.5), the c. 19 objects from Iran (21.2.6), and the 5 objects from Yemen (21.2.7).The material from the South Asia is considered next (21.3): a brief overview of the c. 7,029 ‘archaeological’ objects from India and Sri Lanka (21.3.1) is provided, before a full account of them is set out in Chapter 23.