Sa Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission Mr Kevin Scarce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Body Freezer

BODY IN THE FREEZER the Case of David Szach Acknowledgements I am indebted to editorial comments and suggestions from Jan McInerney, Pat Sheahan, Anthony Bishop, Dr Harry Harding, Michael Madigan, and Dr Bob Moles. Andrew Smart of Blackjacket Studios designed the cover. I especially appreciate the support of my wife, Liz. ISBN: 978-0-9944162-0-9 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Printed in Adelaide by Griffin Press Any enquiries to the author’s email: [email protected] BODY IN THE FREEZER the Case of David Szach TOM MANN Author’s note Following the publication of the Edward Splatt case in Flawed Forensics, David Szach approached me to examine and write up his case. I met with David Szach a number of times to record his version of events and his efforts to clear his name for the murder of lawyer Derrance Stevenson. After examining the trial transcripts, the grounds for appeal, and the reports by forensic scientists investigating the evidence presented by the forensic pathologist, I unravel the crime to reveal its hidden nature and consequences. CONTENTS Introduction … 1 1: Body in the freezer … 3 2: Prime suspect … 7 3: Derrance Stevenson and the Adelaide scene … 21 4: Before the trial … 26 5: Trial evidence … 32 6: Dr Colin Manock’s evidence … 47 7: David Szach’s statement … 60 8: Shaky underpinning for the Crown … 73 9: Blood and fingerprints -

Rear Admiral the Honourable Kevin Scarce AC CSC RAN (Rtd) Royal

Rear Admiral the Honourable Kevin Scarce AC CSC RAN (Rtd) Royal Commissioner Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission GPO Box 11043 Adelaide SA 5001 3 August 2015 Dear Sir, This is my consolidated submission to the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission addressing selected questions from all Issues Papers. Issues Paper One: Exploration, Extraction and Milling My response to Question 1.7 regarding the demand for uranium in the medium and long term is as follows. To begin, I quote the Commissioner from the article titled, “Jobs in nuclear industry are ‘decades away’”, published in The Advertiser on 25 July 2015: “If we decided – and we haven’t decided yet – to recommend parts of the nuclear fuel cycle, it would be a couple of decades before we started to see the major impact.” I submit that at this point in time there is no way to prove a sound basis exists for concluding there will be increased demand for uranium in the medium and long term. No doubt nuclear proponents will point to the world’s increasing energy needs, especially of the two developing giants, China and India. On the demand side, it is true the world will be looking for emissions-free energy on a massive scale to replace traditional fossil fuels. If uranium for producing nuclear energy was the only option to replace fossil fuels, I would not be writing this submission. The fact is, it is not the only option. Another, better option exists in renewable energy, and I submit that in a much shorter time than it would take to establish a nuclear industry in South Australia, the world will be turning to renewables in force while eschewing nuclear energy. -

Citizens' Jury

SUNDAY VERSION South Australia’s Citizens’ Jury on Nuclear Waste Final Report November 2016 “Under what circumstances, if any, could South Australia pursue the opportunity to store and dispose of nuclear waste from other countries?” Jury Summary Statement The Citizens Jury would like to Acknowledge that we have been meeting on Kaurna land and we pay our respects to the Traditional owners, past and present, across South Australia. The jury generally had a strong conviction in taking a position one way or another. Two thirds of the jury do not wish to pursue the opportunity under any circumstances and one third support a commitment to pursue under the circumstances outlined in this report. Introduction: Citizen’s Jury 2 (CJ2) was a group of 350 residents of South Australia who were brought together under the remit of discussing and reporting on the question: “Under what circumstances, if any, could South Australia pursue the opportunity to store and dispose of high level nuclear waste from other countries?”. To be clear, the jury considered only high-level nuclear waste. The people on Citizen’s Jury Two were selected to be broadly representative of the population of South Australia based on demographics (as best as was possible based on the responses to the initial invitation to take part). The 50 jurors from Citizen’s Jury One were also invited back to be part of the second jury process and approximately 30 of them decided to take part in the second jury. On the first day of the jury, we established some guiding principles for how we should approach the process. -

Zoos SA Annual Report 2011-12

zoossa.com.au zoossa.com.au Passion We inspire and influence through our valuable conservation efforts and recognise success. Effectiveness We focus on clearly defined shared goals and support people to achieve them. Innovation We seek creative ways to achieve goals and promote a culture of learning and improving. Integrity We are guided by our values and deliver on our promises. Respect We respect individual’s values and encourage a culture of collaboration, listening and trust. President’s Report .......................................2 CEO’s Report ............................................4 Board Members ...........................................6 List of Achievements ...................................7 The Animals ...........................................11 Conservation ............................................20 Education ................................................23 Sustainability ...........................................24 Visitation .................................................26 Communications & Development .................28 Our People ..............................................34 Assets & Infrastructure ..............................41 Life Members ...........................................42 Finance ...................................................54 AGM Minutes (2011) ................................59 SGM Minutes (2012) .................................62 Zoos South Australia Annual Report 2011/12 1 President’s Report Dusky Langur here is no question that the the overall direction of the business. -

Liquor Licensing Act 1997— Geographical Names Act 1991— (No

No. 81 5191 THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE www.governmentgazette.sa.gov.au PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ALL PUBLIC ACTS appearing in this GAZETTE are to be considered official, and obeyed as such ADELAIDE, THURSDAY, 19 NOVEMBER 2009 CONTENTS Page Page Acts Assented To..................................................................... 5192 Mining Act 1971—Notices ..................................................... 5203 Appointments, Resignations, Etc............................................. 5192 National Parks and Wildlife (National Parks) Regulations Controlled Substances Act 1984—Notice ............................... 5193 2001—Notice....................................................................... 5204 Corporations and District Councils—Notices.......................... 5226 Petroleum and Geothermal Energy Act 2000—Notices .......... 5204 Crown Lands Act 1929—Notice ............................................. 5193 Proclamations .......................................................................... 5214 Development Act 1993—Notice ............................................. 5194 Public Trustee Office—Administration of Estates .................. 5244 Electoral Act 1985—Notice .................................................... 5194 Environment Protection Act 1993—Notices ........................... 5196 REGULATIONS Gas Act 1997—Notice ............................................................ 5194 Liquor Licensing Act 1997— Geographical Names Act 1991— (No. 267 of 2009)............................................................ -

I Remember It As Early November, During a Trip to Sydney

from the publisher GREG T ROSS remember it as early November, during a trip to Sydney. Like surfing, tennis is an integral part of Australian summers. We But it had been going for some time before that. feature too, in this edition, tennis great Rod Laver’s latest book, Memories blur doing events like the recent bushfires but The Golden Era. it started in northern New South Wales and Queensland. We also look at famous Green Bans activist Jack Mundey and Then it seemed like there was a new fire every day in the book on Jack, by his friend and architect, James Colman. The Idifferent parts of the country. It became the greatest natural book, The House That Jack Built, underpins the knowledge that disaster in Australia’s history. preservation of Australia’s historic regions and buildings is just as It impacted The Last Post. I was in Adelaide putting the 21st important now as it was back then. edition together when I received photos of fires close to my house Writer and filmmaker Jemma Pigott writes for The Last Post with in Long Beach, NSW. I flew home and had to spent two nights her story of indigenous veterans, The Coloured Diggers and Wing in Sydney before the roads south opened long enough for me to Commander Mary Anne Whiting takes us to Point Cook in Victoria return home. I walked into an ordeal of some magnitude. Over for a story on the Rededication of the AFC and RAAF Memorial. the next week or so there were orders to leave, as the fires drew We have too, an update on the amazing work being done by closer. -

2015 Annual Report

The University of Adelaide 2015 Annual Report The University of Adelaide 2015 Annual Report To His Excellency, the Honourable Hieu Van Le, AO, Governor of South Australia In accordance with the requirement of Section 25 of the University of Adelaide Act 1971 (1 June 2007), it gives me great pleasure to submit the Report of the Council of the University of Adelaide for the period 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2015. The University Council approved this report at its meeting 30 March 2016. Rear Admiral the Honourable Kevin Scarce, AC, CSC, RAN (Rtd) Chancellor Contents Foreword from the Chancellor 2 From the Vice-Chancellor and President 4 Vision 6 2015 at a glance 6 New performance initiatives 8 Adelaide Enterprise 9 Supporting South Australia’s future prosperity 10 By the numbers 12 Awards and achievements 18 Governance 24 Learning and teaching 30 Research 40 External relations 50 Enablers and supporters 56 Financial statements 60 2015 Annual Report 1 Foreword from the Chancellor As 2015 drew to a close, it gave me the opportunity to reflect on the first year of my appointment as Chancellor of the University of Adelaide. The University has again moved up the Works are proceeding apace on the I would like to thank long-serving University prestigious Times Higher Education World University of Adelaide Health and Medical Council member Mr Charles Bagot, who University Rankings released in October. Sciences (AHMS) building in the City’s retired from Council at the end of 2015, The ranking of 149 follows the University’s West End. When completed in time for having served the University for 12 years. -

Pro Patria Commemorating Service

PRO PATRIA COMMEMORATING SERVICE Forward Representative Colonel Governor of South Australia His Excellency the Honorable Hieu Van Le, AO Colonel Commandant The Royal South Australia Regiment Brigadier Tim Hannah, AM Commanding Officer 10th/27th Battalion The Royal South Australia Regiment Lieutenant Colonel Graham Goodwin Chapter Title One Regimental lineage Two Colonial forces and new Federation Three The Great War and peace Four The Second World War Five Into a new era Six 6th/13th Light Battery Seven 3rd Field Squadron Eight The Band Nine For Valour Ten Regimental Identity Eleven Regimental Alliances Twelve Freedom of the City Thirteen Sites of significance Fourteen Figures of the Regiment Fifteen Scrapbook of a Regiment Sixteen Photos Seventeen Appointments Honorary Colonels Regimental Colonels Commanding Officers Regimental Sergeants Major Nineteen Commanding Officers Reflections 1987 – 2014 Representative Colonel His Excellency the Honorable Hieu Van Le AO Governor of South Australia His Excellency was born in Central Vietnam in 1954, where he attended school before studying Economics at the Dalat University in the Highlands. Following the end of the Vietnam War, His Excellency, and his wife, Lan, left Vietnam in a boat in 1977. Travelling via Malaysia, they were one of the early groups of Vietnamese refugees to arrive in Darwin Harbour. His Excellency and Mrs Le soon settled in Adelaide, starting with three months at the Pennington Migrant Hostel. As his Tertiary study in Vietnam was not recognised in Australia, the Governor returned to study at the University of Adelaide, where he earned a degree in Economics and Accounting within a short number of years. In 2001, His Excellency’s further study earned him a Master of Business Administration from the same university. -

Inquiry Into Nuclear Prohibition

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Environment and Planning Committee Inquiry into nuclear prohibition Parliament of Victoria Legislative Council Environment and Planning Committee Ordered to be published VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER November 2020 PP No 181, Session 2018–2020 ISBN 978 1 922425 12 6 (print version), 978 1 922425 13 3 (PDF version) Committee membership CHAIR DEPUTY CHAIR Cesar Melhem Clifford Hayes Western Metropolitan Southern Metropolitan Dr Matthew Bach Melina Bath Jeff Bourman David Limbrick Eastern Metropolitan Eastern Victoria Eastern Victoria South Eastern Metropolitan Andy Meddick Dr Samantha Ratnam Nina Taylor Sonja Terpstra Western Victoria Northern Metropolitan Southern Metropolitan Eastern Metropolitan Participating members Georgie Crozier, Southern Metropolitan Dr Catherine Cumming, Western Metropolitan Hon. David Davis, Southern Metropolitan Dr Tien Kieu, South Eastern Metropolitan Bev McArthur, Western Victoria Tim Quilty, Northern Victoria ii Legislative Council Environment and Planning Committee About the Committee Functions The Environment and Planning Committee (Legislation and References) is established under the Legislative Council Standing Orders Chapter 23—Council Committees and Sessional Orders. The Committee’s functions are to inquire into and report on any proposal, matter or thing concerned with the arts, environment and planning the use, development and protection of land. The Environment and Planning Committee (References) may inquire into, hold public hearings, consider and report on other matters that are relevant to its functions. The Environment and Planning Committee (Legislation) may inquire into, hold public hearings, consider and report on any Bills or draft Bills referred by the Legislative Council, annual reports, estimates of expenditure or other documents laid before the Legislative Council in accordance with an Act, provided these are relevant to its functions. -

Segments Is the Authorised Journal of the 1 SCIENTIFIC EXPEDITION GROUP INC

Volume 23 Number 3 ISSN 0816-6463 December 2007 SEG MENTS S G Journal of the Scientific Expedition Group E MINNAWARRA BIODIVERSITY PROJECT new and 5 recaptures, half of these being Spring Survey 11 th -14 th October 2007 at Site 4 (flat creekside). Written by Richard Willing Of Antechinus (A. flavipes) there were 9 new and 7 recaptures, the most prolific site being Several factors combined to make this a Site 9 (hill). As usual in spring all were difficult survey. The first was the need to females, several with 7-9 young in the pouch, postpone its start because much of the and a couple of others with pouches recently equipment was away on Expedition vacated. Scrubby Peak; this also reduced the number of volunteers available for setting Only 2 skinks were seen – Hemiergis sp and up the sites and helping during the survey. Shingleback (Tiliqua rugosa). Only 5 Brown As well, a cold snap at the beginning of the Froglets (Crinia signifera) were seen. 2 Grey period reduced all reptile activity resulting shrike-thrushes (Colluricincla harmonica) in reduced numbers of captures. were caught in cage traps at Sites 1 and 3, and there was significant fox disturbance of The good news is that SEG has just been traps at Site 1 on days 3 and 4. Results of awarded an Australia Post Community the bird survey will be available later as it has Development Grant to purchase another not yet been completed. Bats were not set of Elliott traps that will overcome some surveyed. of these problems in the future. -

PASA Journals Index 2017 07 Brian.Xlsx

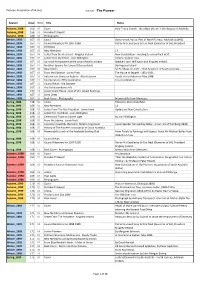

Pioneers Association of SA (Inc) Journal - "The Pioneer" Season Issue Item Title Notes Autumn_1998 166 00 Cover Holy Trinity Church - the oldest church in the diocese of Adelaide. Autumn_1998 166 01 President's Report Autumn_1998 166 02 Photographs Winter_1998 167 00 Cover Government House, Part of North Terrace, Adelaide (c1845). Winter_1998 167 01 Council Members for 1997-1998 Patron His Excellency Sir Eric Neal (Governor of SA), President Winter_1998 167 02 Portfolios Winter_1998 167 03 New Members 17 Winter_1998 167 04 Letter from the President - Kingsley Ireland New Constitution - meeting to review final draft. Winter_1998 167 05 Letter from the Editor - Joan Willington Communication lines. Winter_1998 167 06 Convivial Atmosphere at the Union Hotel Luncheon Speakers Joan Willington and Kingsley Ireland. Winter_1998 167 07 No Silver Spoons for Cavenett Descendants By Kingsley Ireland. Winter_1998 167 08 New Patron Sir Eric Neal, AC, CVO - 32nd Governor of South Australia. Winter_1998 167 09 From the Librarian - Lorna Pratt The House of Seppelt - 1851-1951. Winter_1998 167 10 Autumn sun shines on Auburn - Alan Paterson Coach trip to Auburn in May 1998. Winter_1998 167 11 Incorporation of The Association For consideration. Winter_1998 167 12 Council News - Dia Dowsett Winter_1998 167 13 The Correspondence File Winter_1998 167 14 Government House - One of SA's Oldest Buildings Winter_1998 167 15 Diary Dates Winter_1998 167 16 Back Cover - Photographs Memorabilia from Members. Spring_1998 168 00 Cover Edward Gibbon Wakefield. Spring_1998 168 01 New Members 14 Spring_1998 168 02 Letter From The Vice President - Jamie Irwin Update on New Constitution. Spring_1998 168 03 Letter fron the Editor - Joan Willington Spring_1998 168 04 Ceremonial Toast to Colonel Light By Joan Willington. -

Inquiry Into the Prerequisites for Nuclear Energy in Australia

From: Terry Krieg To: Committee, Environment (REPS) Date: Monday, 2 September 2019 5:31:19 PM Attachments: In the JanSACOME journal articl 2..docx In the 2009 Feb.docx 00.docx My opinion piece prepared for and printed in the Adelaide Review Sept 2009.docx Australia-Ockhams Razor number 4.docx AUSTRALIAmust include nuclear.docx SOUTH AUSTRALIANuclear our saviour..docx A submission from Terry Krieg,BA Dip Ed on the Inquiry into the prerequisites for nuclear energy in Australia. Some biographical details about the author. 1. Lives in Port Lincoln - born 26/06/1938 2.Retired secondary school Deputy Principal and teacher of mainly senior secondary geography and geology from 1959 - 1992. 3. Studied geology and climatology as part of a BA degree at University of Adelaide 1956-58.. Retired from teaching 1992. 4 Established an ecotourism business in 1993 which was closed in 2017. 5. Conducted over 150 tours for international and Australian groups mostly in the inland of South Australia especially the Flinders Ranges and Lake Eyre. 6. Experienced bush walker having walked around Lake Eyre in 1982, in the Simpson Desert, the Willouran Ranges and,the entire Flinders Ranges including the Gammon Ranges.Leader of many bush walking expeditions for both student and adult groups [1980 - 2014]. 7.Spent 1981 on teacher exchange in Toronto, Canada where he became familiar with the nuclear industry.Converted from anti to pro nuclear during that year. 8. Began speaking for and promoting nuclear power for Australia in 1998 when the establishment of a national low/medium level nuclear waste repository on Arcoona Station near Woomera was discussed.