The Nineteenth-Century Italian Translators of Lord Byron's Marino

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frederic Ozanam, a Life in Letters

OTHER BOOKS BY JOSEPH I. DIRVIN, C.M. St. Catherine Laboure of the Miraculous Medal Farrar, Straus & Cudahy, New York, 1958; reissue Tan Books and Publishers, Rockland, Illinois 1984. Woman Clothed With the Sun (Collaboration), Hanover House, New York, 1960. Mrs. Seton, Foundress of the American Sisters of Charity Farrar, Straus & Cudahy, New York, 1962, 1975. Louise de Marillac Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York, Spring, 1970. Frederic Ozanam A LIFE IN LETTERS ' " , ~~ , ,-·~-- . ,, ~~~ Frederic Ozanam 1813-1853 ~ Frederic Ozanam A LIFE IN LETTERS Translated and edited by JOSEPH I. DIRVIN, C.M. SOCIETY OF ST. VINCENT DE PAUL COUNCIL OF THE UNITED STATES © 1986 by Society of St. Vincent de Paul, Council of the United States, 4140 Lindell, St. Louis, Missouri 63108 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ozanam, A.-F. (Antoine Frederic), 1813-1853. Frederic Ozanam, a life in letters. Includes index. 1. Ozanam, A.-F. (Antoine Frederic), 1813-1853- Correspondence. 2. Catholics-France-Correspondence. 3. Society of St. Vincent de Paul. I. Dirvin, Joseph I. II. Title. BX4705.08A4 1986 282'.092'4 [B] 86-26127 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 FOREWORD The Council of the United States has taken on the responsibility of publishing an annotated English translation of selected correspondence of our Frederic Ozanam. This praiseworthy effort is made possible by the unselfish labor of Father Joseph I. Dir, vin, C.M., who has translated the letters from the original French. -

ENG3U Free Choice Reading

ENG3U Free-Choice Reading • Name: ______________ Individual Free-Choice Reading Assignment 1 Free Choice Important Literary Authors by Period & Culture Beginning to 1st 2nd-15th 16th Century 17th Century 18th Century 19th Century 20th Century Century A.D. Century (1500s) (1600s) (1700s) (1800s) (1900s) Indian Manu, Valmiki Chandidas, The Ghazal Khan Kushal Mirza Ghalib Mahatma Subcontinental Kabir Gandhi, Premchand Chinese I Ching, Tao Yangming Hong Shen Yuan Mei, Mao Zedong, Confucius Yuanming, Xie Wang, Wu Cao Xueqin Lin Yutang Lingyun Cheng’en Japanese Manyoshu Zeami Kojiro Kanze Matsuo Basho Hakuin Ekaku Natsume Mishima Motokiyo Soseki Yukio Middle Eastern Gilgamesh, Book Talmud, Jami, Thousand and Evliya Çelebi Jacob Talmon, of the Dead, The Rumi One Nights David Shar, Bible Amos Oz Greek Homer, Aesop, Anna Dionysios Constantine Sophocles, Comnena, Solomos Cavafy, Euripides Ptolemy, Giorgos Galen, Seferis, Porphyry Odysseas Elytis Latin Virgil, Ovid, St. Anselm of Desiderius Johannes Carolus Pope Pius X, Cicero Aosta, St. Erasmus, Kepler, Linnaeus XI, XII Thomas Thomas Baruch Aquinas, St. Moore, John Spinoza Augustine Calvin Germanic Neibelungenli Martin Luther Johann Immanuel Johann Rainer Maria ed, Van Grimmelshau Kant, Wolfgang von Rilke, Bertolt Eschenbach, sen Friedrich von Goethe, Brecht, Albert Von Schiller Brothers Schweitzer Strassburg Grimm, Karl Marx, Henrik Ibsen French Le Chanson Robert René Voltaire, Jean- Honoré de Marcel Proust, de Roland, Garnier, Descartes, Jacques Balzac Victor Jean-Paul Jean Froissart, Marguerite -

La Prison Romantique: Silvio Pellico, Stendhal

La prison romantique: Silvio Pellico, Stendhal Pendant que certains auteurs du XIXe siècle, comme Tolstoï, Dickens et Dostoïevski, font de la prison un lieu permettant d’accéder à la connaissance et d’articuler une attitude critique vis-à-vis de la société de l’époque, d’autres utilisent l’enfermement comme un miroir de leur âme blessée par un monde malveillant et cruel. Déçus, trahis par la société, las d’un rationalisme qui brime leurs sentiments, ils voient dans la prison le seul refuge pouvant les protéger des malheurs de la vie sur terre. Loin de représenter une punition, la privation de la liberté devient le moyen pour fuir une réalité hostile, pour retourner en quelque sorte dans le ventre de la mère1 et se soustraire ainsi aux contraintes que la vie quotidienne impose aux sentiments et à l’imagination. Là-dessus viennent se greffer tous les sujets chers au romantisme : l’amour, la solitude, le plaisir de la souffrance, la rêverie.2 Déjà présents dans le « Roi Lear »3 de Shakespeare et dans « Le prisonnier de Chillon » de Byron, ces thèmes seront repris au XIXe siècle par Baudelaire, Gérard de Nerval, Stendhal et, en Italie, par Silvio Pellico. Au-delà des différences qui caractérisent ces auteurs, ceux-ci partagent le même désir pour un lieu en dehors du temps et de l’espace, pourvoyeur d’une paix de l’esprit que le monde réel n’est pas à même d’offrir. La thèse de la « prisonisation », selon ces auteurs, doit être lue à l’envers : ce n’est pas la prison qui crée une dépendance, mais bien le besoin de solitude et de sérénité intérieure inhérent à tout être 1 Cf. -

Shakespeare in Italy Author(S): Agostino Lombardo Source: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol

Shakespeare in Italy Author(s): Agostino Lombardo Source: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 141, No. 4 (Dec., 1997), pp. 454-462 Published by: American Philosophical Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/987221 Accessed: 01-04-2020 11:03 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms American Philosophical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society This content downloaded from 94.161.168.118 on Wed, 01 Apr 2020 11:03:37 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Shakespeare in Italy AGOSTINO LOMBARDO Dipartimento di Anglistica, Universita di Roma, "La Sapienza" it hacius, Spenns, Drayton, Shakespier ... ": in this list of confused and mangled names we find the first mention of Shakespeare in Italian writing. The author was probably that brilliant and versatile essayist, Lorenzo Magalotti, who wrote in 1667 the account of a journey to England. The account, indeed, gives such an interesting description of life in Restoration London as to make us regret the complete absence of any allusions to the Shakespearean performances Magalotti must have attended, as he did others of a more frivolous nature ("Wrestling, bull and bear baiting. -

MACBETH Music by Giuseppe Verdi Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave

MACBETH Music by Giuseppe Verdi Libretto by Francesco Maria Piave & Andrea Maffei Based on the play by William Shakespeare First performed on March 14, 1847 in Florence Characters Macbeth (baritone), Thane of Cawdor Lady Macbeth (soprano) Banquo (bass), A General Macduff (tenor), A Nobleman Malcolm (tenor), son of King Duncan Lady-In-Waiting to Lady Macbeth (soprano) A Physician (bass) A Murderer (baritone) Three Apparitions: A warrior (baritone) A bloody child (soprano) A crowned child (soprano) A manservant (Bass) King Duncan, Fleance (son of Banquo), Attendants, Messengers, Soldiers, Assassins, Witches, Lords and Ladies, Refugees Act 1 Macbeth and Banquo, both generals under King Duncan, come upon a group of witches who foretell their futures: Macbeth will become the Thane of Cawdor, and then King; Banquo will become father of kings. Soldiers bring the news that Macbeth has been named Thane of Cawdor. Amazed by the truth of the prophecies, Macbeth begins to imagine himself as the King (“Due vaticini..”). At Dunsinane, Macbeth’s estate, Lady Macbeth reads a letter she received from her husband recounting his meeting with the witches and the outcome of their predictions. Exulting in this news, she waits impatiently for his arrival and makes plans to pressure Macbeth to act, rather than wait for events to take their course (“Vieni! t’affretta!” -- Come, then! Hasten!). A messenger brings news that King Duncan will be their guest that evening. When Macbeth arrives, she urges him to kill the king that night. In his extended arioso “Mi si affaccia un pugnal?!” (Is this a dagger that appears to me?), Macbeth sees a vision of a bloody dagger and gathers his courage to perform the deed. -

From Coppet to Milan: Romantic Circles at La Scala

From Coppet to Milan: Romantic Circles at La Scala Carmen Casaliggi Cardiff Metropolitan University When Percy Shelley left England and settled with Mary Godwin and Claire Clairmont at Maison Chapuis close to Villa Diodati in May 1816, his thoughts naturally turned to the people who were part of the coterie of European writers and artists visiting Switzerland during that Summer. As he wrote in a letter to Thomas Jefferson Hogg dated July 18, 1816: “Lord Byron, whom I have seen at this place, is about to publish a new canto of Childe Harold [...] Mad. de Stael [sic] is here & a number of literary people whom I have not seen, & indeed have no great curiosity to see” (493). Despite their strident disagreement over the merits of Byron’s entourage, Shelley’s words are suggestive of the significance of Switzerland as a centre of creativity and inspiration; it also becomes an important site to test authentic forms of sociability. John William Polidori’s diary entry for May 25, 1816 – written only few days after he arrived in Switzerland as Byron’s personal physician - retraces the footsteps of writers and philosophers interested in Swiss destinations: “It is a classic ground we go over. Buonaparte, Joseph, Bonnet, Necker, Staël, Voltaire, Rousseau, all have their villas (except Rousseau). Genthoud, Ferney, Coppet are close to the road” (96). This distinctive association of the biographical, the historical, and the geographical indicates the extent to which the Swiss experience can be seen as one of the first Romantic examples of influence and collaboration between British and European Romantic writers. -

![Unless by the Lawful Judgment of Their Peers [.Lat., Nisi Per Legale Judicum Parum Suorum] ,Unattributed Author - Magna Charta--Privilege of Barons of Parliament](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4577/unless-by-the-lawful-judgment-of-their-peers-lat-nisi-per-legale-judicum-parum-suorum-unattributed-author-magna-charta-privilege-of-barons-of-parliament-1144577.webp)

Unless by the Lawful Judgment of Their Peers [.Lat., Nisi Per Legale Judicum Parum Suorum] ,Unattributed Author - Magna Charta--Privilege of Barons of Parliament

.Unless by the lawful judgment of their peers [.Lat., Nisi per legale judicum parum suorum] ,Unattributed Author - Magna Charta--Privilege of Barons of Parliament Law is merely the expression of the will of the strongest for the time being, and .therefore laws have no fixity, but shift from generation to generation Henry Brooks Adams - .The laws of a state change with the changing times Aeschylus - .Where there are laws, he who has not broken them need not tremble ,It., Ove son leggi] [.Tremar non dee chi leggi non infranse (Vittorio Alfieri, Virginia (II, 1 - .Law is king of all Henry Alford, School of the Heart - (lesson 6) .Laws are the silent assessors of God William R. Alger - Written laws are like spiders' webs, and will like them only entangle and hold the .poor and weak, while the rich and powerful will easily break through them Anacharsis, to Solon when writing his laws - Law; an ordinance of reason for the common good, made by him who has care of the .community Saint Thomas Aquinas - .Law is a bottomless pit ,John Arbuthnot - (title of a pamphlet (about 1700 .Ancient laws remain in force long after the people have the power to change them Aristotle - At his best man is the noblest of all animals; separated from law and justice he is the .worst Aristotle - .The law is reason free from passion Aristotle - .Whereas the law is passionless, passion must ever sway the heart of man Aristotle - .Decided cases are the anchors of the law, as laws are of the state Francis Bacon - One of the Seven was wont to say: "That laws were like cobwebs; where the small ".flies were caught, and the great brake through (Francis Bacon, Apothegms (no. -

In PDF Format

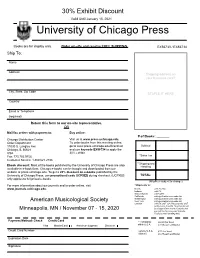

30% Exhibit Discount Valid Until January 15, 2021 University of Chicago Press Books are for display only. Order on-site and receive FREE SHIPPING. EX56733 / EX56734 Ship To: Name Address Shipping address on your business card? City, State, Zip Code STAPLE IT HERE Country Email or Telephone (required) Return this form to our on-site representative. OR Mail/fax orders with payment to: Buy online: # of Books: _______ Chicago Distribution Center Visit us at www.press.uchicago.edu. Order Department To order books from this meeting online, 11030 S. Langley Ave go to www.press.uchicago.edu/directmail Subtotal Chicago, IL 60628 and use keycode EX56734 to apply the USA 30% exhibit Fax: 773.702.9756 *Sales Tax Customer Service: 1.800.621.2736 **Shipping and Ebook discount: Most of the books published by the University of Chicago Press are also Handling available in e-book form. Chicago e-books can be bought and downloaded from our website at press.uchicago.edu. To get a 20% discount on e-books published by the University of Chicago Press, use promotional code UCPXEB during checkout. (UCPXEB TOTAL: only applies to full-priced e-books (All prices subject to change) For more information about our journals and to order online, visit *Shipments to: www.journals.uchicago.edu. Illinois add 10.25% Indiana add 7% Massachusets add 6.25% California add applicable local sales tax Washington add applicable local sales tax American Musicological Society New York add applicable local sales tax Canada add 5% GST (UC Press remits GST to Revenue Canada. Your books will Minneapolis, MN / November 07 - 15, 2020 be shipped from inside Canada and you will not be assessed Canada Post's border handling fee.) Payment Method: Check Credit Card ** If shipping: $6.50 first book Visa MasterCard American Express Discover within U.S.A. -

EJ Full Draft**

Reading at the Opera: Music and Literary Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Italy By Edward Lee Jacobson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfacation of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mary Ann Smart, Chair Professor James Q. Davies Professor Ian Duncan Professor Nicholas Mathew Summer 2020 Abstract Reading at the Opera: Music and Literary Culture in Early Nineteenth-Century Italy by Edward Lee Jacobson Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Mary Ann Smart, Chair This dissertation emerged out of an archival study of Italian opera libretti published between 1800 and 1835. Many of these libretti, in contrast to their eighteenth- century counterparts, contain lengthy historical introductions, extended scenic descriptions, anthropological footnotes, and even bibliographies, all of which suggest that many operas depended on the absorption of a printed text to inflect or supplement the spectacle onstage. This dissertation thus explores how literature— and, specifically, the act of reading—shaped the composition and early reception of works by Gioachino Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti, and their contemporaries. Rather than offering a straightforward comparative study between literary and musical texts, the various chapters track the often elusive ways that literature and music commingle in the consumption of opera by exploring a series of modes through which Italians engaged with their national past. In doing so, the dissertation follows recent, anthropologically inspired studies that have focused on spectatorship, embodiment, and attention. But while these chapters attempt to reconstruct the perceptive filters that educated classes would have brought to the opera, they also reject the historicist fantasy that spectator experience can ever be recovered, arguing instead that great rewards can be found in a sympathetic hearing of music as it appears to us today. -

Biography of Sismondi

1 BIOGRAPHY OF SISMONDI HELMUT O. PAPPE I. Jean Charles Léonard Simonde was born on the 9th May 1773 into a Genevan family. In later life he changed his family to de Sismondi after an old Pisan aristocratic family from which he believed the Simondis to be descended. Charles’s parents were the pasteur Gèdèon François Simonde and his wife Henriette Ester Gabriele Girodz; a sister, Sara, called Serina by the family and her friends, saw the light of day two years later. The families of both parents were du haut the Simondes being on the borderline between nobility and upper bourgeoisie, the Girodz being members of the well-to-do upper bourgeoisie. Both the Simondes and the Girodz had come to Geneva as members of the second éimgration after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, that is, both families were Protestant fugitives from religious persecution in France. The Girodz had come to Geneva from Chàlons-sur-Saône in 1689. Henriette’s father, Pierre Girodz, became a successful and highly respected businessman engaged in various commercial enterprises connected with the watchmaking trade. He owned a substantial town house close to the cathedral in the Bourg-de-Four and an imposing country seat ‘Tourant’ at Chênes, both to be the residences of Sismondi after his return from exile in Italy. On the occasion of the marriage of his daughter on the 12th January 1770 Pierre Girodz was able to give her a dowry his town house worth 30,000 Livres as well as 10,000 Livres in cash and 2,000 Livres worth of jewellery. -

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Summer Quarter 2017 (July - September) A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

CHAN 3086 BOOK.Qxd 21/5/07 5:36 Pm Page 2

CHAN 3086 Book Cover.qxd 21/5/07 5:33 pm Page 1 CHAN 3086(2) CHANDOS O PERA IN ENGLISH CHAN 3086 BOOK.qxd 21/5/07 5:36 pm Page 2 Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924) Turandot Lyric drama in three acts Libretto by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni, after Gozzi’s dramatic fairy-tale Lebrecht Music Collection Music Lebrecht Princess Turandot............................................................................................Jane Eaglen soprano The Emperor Altoum, her father....................................................................Nicolai Gedda tenor Timur, the dispossessed King of Tartary...............................................................Clive Bayley bass Calaf, his son.................................................................................................Dennis O’Neill tenor Liù, a slave-girl ................................................................................................Mary Plazas soprano Ping, Grand Chancellor ............................................................................Peter Sidhom baritone Pang, General Purveyor Ministers ..............................................................Mark Le Brocq tenor Pong, Chief Cook } ...................................................................................Peter Wedd tenor A Mandarin .................................................................................................Simon Bailey baritone Prince of Persia ..............................................................................................Mark Le Brocq tenor