Behind the Scenes at the National Theatre by Sir Nicholas Hytner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

About Queenspark Books

About QueenSpark Books QueenSpark Books was founded in 1972 as part of a campaign to save the historic Royal Spa in Brighton's Queen's Park from being converted to a casino. The campaign was successful and it inspired participants to start collecting memories of people living in Brighton and Hove to preserve for future generations. QueenSpark Books is now the longest-running organisation of its kind in the UK. th More than one hundred books later, as part of our 45 anniversary celebrations, we are making the original texts of many of our out-of-print books available for the first time in many years. We thank you for choosing this book, and if you can make a donation to QueenSpark Books, please click on the “donate” button on the book page on our website. This book remains the copyright of QueenSpark Books, so if reproducing any part of it, please ensure you credit QueenSpark Books as publisher. Foreword – Pullman Attendant by Bert Hollick, 1991 In 1935, fifteen year old Bert Hollick signed on at Brighton Station for his first shift on a Pullman Train. Working on the midnight shift from Victoria to Brighton including the famous Brighton Belle, he learned to ladle soup from a tureen at seventy-five miles per hour and serve a three-course lunch in a speedy fifty-eight minutes. Bert’s life story is told in a style that conveys wonderfully the atmosphere of the Pullman Cars, as well as providing interesting factual details of railway life. Bert worked at a time when a twelve to fourteen hour day was commonplace, and wages were a meagre £2 a week, despite providing a luxury service to everyday travellers. -

Dance Theatre in Notes

THEATRICAL COLLOQUIA DOI Number: 10.1515/tco-2017-0026 Dance Theatre in Notes Alice-Maria SAFTA Abstract: The fusing of arts enriches a spectacular setting for all human feelings to thrive and express themselves. The theatre in the arts and the art in the theatre, a sublime melding of purity and mystery, speaks striking truths for those with ears to hear them. “The floors” of theatres today enjoy classical dramatic pieces, as well as the staging of experiments, which in my opinion are a real necessity for the entire development of the creative human spirit. The need for free speech and expression gives us motivation to explore the meaning of the term “classical”. The latest trends in the art of modern dance are represented by a return to expression and theatricality, the narrative genre, as well as the historical account of the development of the plot, the restoration interventions in spoken word, chanting and singing; the concepts of art are undergoing a full recovery. Key words: fusion arts, performance roots, modern art, music hall and Jazz, primitive and current dance The fusing of arts enriches a spectacular setting for all human feelings to thrive and express themselves. The theatre in arts and the art in the theatre are a sublime melding of purity and mystery, speaking striking truths for those with ears to hear them. “The floors” of theatres today enjoy classical dramatic pieces, as well as the staging of experiments, which in my opinion are a real necessity for the entire development of the creative human spirit. The need for free speech and expression gives motivation for us to explore the meaning of the term “classical”. -

One Man, Two Guvnors by Richard Bean Based on the Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldoni, with Songs by Grant Olding Background Pack

One Man, Two Guvnors by Richard Bean based on The Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldoni, with songs by Grant Olding Background pack The National's production 2 Carlo Goldoni 3 Commedia dell'arte 4 One Man, Two Guvnors – a background 5 Lazzi – comic set pieces 7 Characters 9 Rehearsal overview 10 In production: from the Lyttelton to the Adelphi 13 In production: Theatre Royal Haymarket 14 Richard Bean interview 15 Grant Olding Interview 17 Further production detailsls: This background pack is Director Learning Workpack writer www.onemantwoguvnors.com published by and copyright Nicholas Hytner National Theatre Adam Penford The Royal National Theatre South Bank Board London SE1 9PX Editor Reg. No. 1247285 T 020 7452 3388 Ben Clare Registered Charity No. F 020 7452 3380 224223 E discover@ Views expressed in this nationaltheatre.org.uk Rehearsal and production workpack are not necessarily photographs those of the National Theatre Johan Persson National Theatre Learning Background Pack 1 The National’s production The production of One Man, Two Guvnors opened in the National’s Lyttelton Theatre on 24 May 2011, transferring to the Adelphi from 8 November 2011; and to the Theatre Royal Haymarket with a new cast from 2 March 2012. The production toured the UK in autumn 2011 and will tour again in autumn 2012. The original cast opened a Broadway production in May 2012. Original Cast (National Theatre and Adelphi) Current Cast (Theatre Royal Haymarket) Dolly SuzIE TOASE Dolly JODIE PRENGER Lloyd Boateng TREvOR LAIRD Lloyd Boateng DEREk ELROy Charlie -

Ntlive OM2G Castlist UK A4 RE 13 09 19.Indd

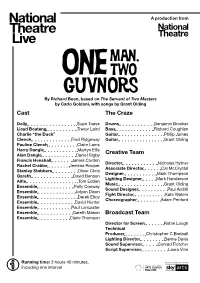

Did you know? A production from In 2018 we had 19,940 screenings around the world. By Richard Bean, based on The Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldoni, with songs by Grant Olding Cast The Craze Enjoy the show Dolly Suzie Toase Drums Benjamin Brooker Lloyd Boateng Trevor Laird Bass Richard Coughlan We hope you enjoy your National Theatre Please do let us know what you think Charlie “the Duck” Guitar Philip James Live screening. We make every attempt to through our channels listed below or Clench Fred Ridgeway Guitar Grant Olding replicate the theatre experience as closely approach the cinema manager to share Pauline Clench Claire Lams as possible for your enjoyment. your thoughts. Harry Dangle Martyn Ellis Creative Team Alan Dangle Daniel Rigby Francis Henshall James Corden Director Nicholas Hytner Rachel Crabbe Jemima Rooper Associate Director Cal McCrystal Stanley Stubbers Oliver Chris Connect with us Designer Mark Thompson Gareth David Benson Lighting Designer Mark Henderson A l fi e Tom Edden Music Grant Olding Explore Never miss out Ensemble Polly Conway Sound Designer Paul Arditti Go behind the scenes of One Man, Two Get the latest news from Ensemble Jolyon Dixon Fight Director Kate Waters Guvnors and learn more about how our National Theatre Live straight Ensemble Derek Elroy Choreographer Adam Penford broadcasts happen on our website. to your inbox. Ensemble David Hunter Ensemble Paul Lancaster Broadcast Team ntlive.com ntlive.com/signup Ensemble Gareth Mason Ensemble Claire Thomson Director for Screen Robin Lough Technical Join in Feedback Producer Christopher C.Bretnall Lighting Director Bernie Davis Use #OneManTwoGuvnors and be Share your thoughts by taking our Sound Supervisor Conrad Fletcher a part of the conversation online. -

Anna Nicole Composed by Mark-Anthony Turnage Libretto by Richard Thomas Directed by Richard Jones Conducted by Steven Sloane

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #AnnaNicole Brooklyn Academy of Music New York City Opera Alan H. Fishman, Charles R. Wall, Chairman of the Board Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, George Steel, Vice Chairman of the Board General Manager and Artistic Director Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Jayce Ogren Music Director Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Joseph V. Melillo, present Executive Producer Anna Nicole Composed by Mark-Anthony Turnage Libretto by Richard Thomas Directed by Richard Jones Conducted by Steven Sloane BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Sep 17, 19, 21, 24, 25, 27 & 28 at 7:30pm Approximate running time: two hours and 30 minutes including one intermission Anna Nicole was commissioned by the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London and premiered there in February 2011 Set design by Miriam Buether Costume design by Nicky Gillibrand Leadership support for opera at BAM provided by: Lighting design by Mimi Jordan Sherin & D.M. Wood The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Choreography by Aletta Collins The Peter Jay Sharp Foundation Stage director Richard Gerard Jones Stavros Niarchos Foundation Supertitles by Richard Thomas Major support provided by Chorus master Bruce Stasyna Aashish & Dinyar Devitre Musical preparation Myra Huang, Susanna Stranders, Lynn Baker, Saffron Chung Additional support for opera at BAM provided by The Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust Production stage manager Emma Turner Stage managers Samantha Greene, Jenny Lazar New York City Opera’s Leadership support for Assistant stage director Mike Phillips Anna Nicole provided by: Additional casting by Telsey + Company, Tiffany Little John H. and Penelope P. Biggs Canfield, CSA Areté Foundation, Edward E. -

One Man, Two Guvnors by Richard Bean Based on the Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldoni with Songs by Grant Olding Background Pack

One Man, Two Guvnors by Richard Bean based on The Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldoni with songs by Grant Olding Background pack The National's production 2 Carlo Goldoni 3 Commedia dell'arte 4 One Man, Two Guvnors - a background 5 Lazzi - comic set pieces 7 Characters 9 Rehearsal overview 10 Richard Bean interview 13 Photo (James Corden) by Phil Fisk Grant Olding Interview 15 Further production detailsls: This background pack is Director Discover Workpack writer nationaltheatre.org.uk published by and copyright Nicholas Hytner National Theatre Adam Penford The Royal National Theatre South Bank Board London SE1 9PX Editor Reg. No. 1247285 T 020 7452 3388 Ben Clare Registered Charity No. F 020 7452 3380 224223 E discover@ Views expressed in this nationaltheatre.org.uk Rehearsal and production workpack are not necessarily photographs those of the National Theatre Johan Persson discover: National Theatre Background Pack 1 This production of One Man, Two Guvnors opened The National’s production in the National’s Lyttelton Theatre on 24 May 2011 Dolly SUZIE TOASE Lloyd Boateng TREVOR LAIRD Charlie “the Duck” Clench FRED RIDGEWAY Pauline Clench CLAIRE LAMS Harry Dangle MARTYN ELLIS Alan Dangle DANIEL RIGBY Francis Henshall JAMES CORDEN Rachel Crabbe JEMIMA ROOPER Stanley Stubbers OLIVER CHRIS Gareth DAVID BENSON Alfie TOM EDDEN Ensemble POLLY CONWAY JOLYON DIXON DEREK ELROY PAUL LANCASTER FERGUS MARCH GARETH MASON CLARE THOMSON Director NICHOLAS HYTNER Associate Director CAL McCRYSTAL Designer MARK THOMPSON Lighting Designer MARK HENDERSON Music GRANT OLDING Sound Designer PAUL ARDITTI Fight Director KATE WATERS Choreographer & Staff Director ADAM PENFORD Company Voice Work KATE GODFREY discover: National Theatre Background Pack 2 Carlo Goldoni Carlo Goldoni was born in 1707 into a a series of plays, experimenting with form middle-class family in Venice. -

Download the Cast List

A production from By Richard Bean, based on The Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldoni, with songs by Grant Olding Cast The Craze Dolly Suzie Toase Drums Benjamin Brooker Lloyd Boateng Trevor Laird Bass Richard Coughlan Charlie “the Duck” Guitar Philip James Clench Fred Ridgeway Guitar Grant Olding Pauline Clench Claire Lams Harry Dangle Martyn Ellis Creative Team Alan Dangle Daniel Rigby Francis Henshall James Corden Director Nicholas Hytner Rachel Crabbe Jemima Rooper Associate Director Cal McCrystal Stanley Stubbers Oliver Chris Designer Mark Thompson Gareth David Benson Lighting Designer Mark Henderson Alfie Tom Edden Music Grant Olding Ensemble Polly Conway Sound Designer Paul Arditti Ensemble Jolyon Dixon Fight Director Kate Waters Ensemble Derek Elroy Choreographer Adam Penford Ensemble David Hunter Ensemble Paul Lancaster Ensemble Gareth Mason Broadcast Team Ensemble Claire Thomson Director for Screen Robin Lough Technical Producer Christopher C.Bretnall Lighting Director Bernie Davis Sound Supervisor Conrad Fletcher Script Supervisor Laura Vine Running time: 2 hours 40 minutes, including one interval Did you know? In 2019 we had 26,426 screenings around the world. Introducing National Theatre at Home We’re all about experiencing theatre Following One Man, Two Guvnors, each together. At a time when many theatre fans week a different production will be made around the world aren’t able to visit National available to watch for free via the National Theatre Live venues or local theatres, we’re Theatre’s YouTube channel on Thursdays excited to bring you One Man, Two Guvnors at 7pm UK-time and will then be via National Theatre at Home. -

THEATRE in ENGLAND 2012-13 UNIVERSITY of ROCHESTER Mara Ahmed

THEATRE IN ENGLAND 2012-13 UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER Mara Ahmed The Master and Margarita Barbican Theatre 12/28/12 Based on Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel, this adaptation by Simon McBurney is as inventive and surprising as the book’s storyline. Satan disguised as Professor Woland visits Stalinist Russia in the 1930s. He and his violent retinue use their black magic and death prophesies to dispose of people and take over their apartments; most villainy and betrayal in the play is in fact motivated by the acquisition of apartment space. Bulgakov is satirizing the restriction of private space in Stalin’s Russia but buildings are also a metaphor for the structure of society as a whole. Rooms are demarcated by light beams, in the constantly changing set design, in order to emphasize relative boundaries and limits. The second part of the play focuses on Margarita and her lover, a writer who has just finished a novel about the complex relationship between Pontius Pilate (the Roman procurator of Judaea) and Yeshua ha-Nostri (Jesus, a wandering philosopher). Margarita calls him the Master on account of his brilliant literary chef d’oeuvre. She is devoted to him. However, the Master’s novel is ridiculed by the Soviet literati and after being denounced by a neighbor, he is taken into custody and ends up at a lunatic asylum. The parallels between his persecution and that of his principal character, Jesus, are brought into relief by constant shifts in time and place, between Moscow and Jerusalem. Margarita makes a bargain with Satan on the night of his Spring Ball, which she agrees to host, and succeeds in saving the Master. -

“Fascinating Facts” August 2018

Daily Sparkle CD - A Review of Famous Songs of the Past “Fascinating Facts” August 2018 Track 1 On Top of Old Smokey On Top of Old Smoky is a traditional folk song and a well-known ballad of the United States. Old Smoky may be a high mountain somewhere in the Ozarks or the central Appalachians, as the tune bears the stylistic hallmarks of the Scottish and Irish people who settled the region. Mitchell "Mitch" Miller (July 4, 1911 – July 31, 2010) was prominent in the American music industry. Miller was involved in almost all aspects of the industry, working as a musician, singer, conductor, record producer and record company executive. Miller was one of the most influential people in American popular music during the 1950s and early 1960s, both as the head of A&R at Columbia Records and as a best-selling recording artist with an NBC television series, Sing Along with Mitch. Track 2 Island In The Sun A song comprised of traditional Jamaican music. Belafonte starred in a film of the same name in 1957. Harry Belafonte born Harold George "Harry" Belafonte, Jr. (born March 1, 1927) is an American singer, songwriter, actor and social activist. He was dubbed the "King of Calypso" for popularizing the Caribbean musical style with an international audience in the 1950s. Belafonte is perhaps best known for singing The Banana Boat Song, with its signature lyric "Day-O". Throughout his career he has been an advocate for civil rights and humanitarian causes and was a vocal critic of the policies of the George W. -

One Man, Two Guvnors by Richard Bean Based on the Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldoni, with Songs by Grant Olding Background Pack

One Man, Two Guvnors by Richard Bean based on The Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldoni, with songs by Grant Olding Background pack The National Theatre's production 2 Carlo Goldoni 3 Commedia dell'arte 4 One Man, Two Guvnors – a background 5 Lazzi – comic set pieces 7 Characters 9 Rehearsal overview 10 In production: from the Lyttelton to the Adelphi 13 In production: Theatre Royal Haymarket 14 Richard Bean interview 15 Grant Olding Interview 17 Further production detailsls: This background pack is Director Learning Workpack writer onemantwoguvnors.com published by and copyright Nicholas Hytner National Theatre Adam Penford The Royal National Theatre South Bank with contributions from Board London SE1 9PX Lisa Blair and Katie Lewis Reg. No. 1247285 T 020 7452 3388 Registered Charity No. F 020 7452 3380 Editor 224223 E learning Ben Clare Views expressed in this @nationaltheatre.org.uk workpack are not necessarily Rehearsal and production those of the National Theatre photographs Johan Persson Poster photographs Hugo Glendinning National Theatre Learning Background Pack 1 The National Theatre’s production The production of One Man, Two Guvnors opened in the National’s Lyttelton Theatre on 24 May 2011, transferring to the Adelphi from 8 November 2011; and to the Theatre Royal Haymarket with a new cast from 2 March 2012. The production toured the UK in autumn 2011, the UK and internationally in autumn 2012 and tours the UK and Ireland in spring 2014. The original cast opened a Broadway production in May 2012. Original Cast (National Theatre -

Curriculum Vitae

Ginny Schiller CDG 9 Clapton Terrace London E5 9BW Casting Director Tel: 020 8806 5383 Mob: 07970 517667 [email protected] curriculum vitae I am an experienced casting director with nearly 20 years in the industry. My casting career began at the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1997 and I went freelance in 2001. I have collaborated on hundreds of productions with dozens of directors, producers and venues, and although my main focus has always been theatre, I have also cast for television, film, radio and commercials. I have been an in-house casting director for Chichester Festival Theatre, Rose Theatre Kingston, English Touring Theatre and Soho Theatre and returned to the RSC in 2005/6 to lead the casting for the Complete Works Season. I currently work closely with Danny Moar on many of the shows for Theatre Royal Bath Productions and with Laurence Boswell at the Ustinov Studio Theatre. I have cast for independent commercial producers as well as the subsidised sector, for the touring circuit, regional, fringe and West End venues, including the Almeida, Arcola, ATG, Birmingham Rep, Bolton Octagon, Bristol Old Vic, City of London Sinfonia, Clwyd Theatr Cyrmu, Frantic Assembly, Greenwich Theatre, Hampstead Theatre, Headlong, Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse, Lyric Theatre Belfast, Marlowe Studio Canterbury, Menier Chocolate Factory, New Wolsey Ipswich, Norfolk & Norwich Festival, Northampton Royal & Derngate, Oxford Playhouse, Plymouth Theatre Royal and Drum, Regent's Park Open Air Theatre, Shared Experience, Sheffield Crucible, Sonia Friedman Productions, Theatre Royal Haymarket, Touring Consortium, Young Vic, West Yorkshire Playhouse, Yvonne Arnaud and Wilton’s Music Hall. I am currently on the committee of the Casting Directors’ Guild, and actively involved in discussions with Equity regarding the casting process and diversity issues across the media. -

One Man, Two Guvnors

ONE MAN, TWO GUVNORS BY RICHARD BEAN DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. ONE MAN, TWO GUVNORS Copyright © 2011, Richard Bean All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of ONE MAN, TWO GUVNORS is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for ONE MAN, TWO GUVNORS are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee.