Different0403.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Back Numbers 9

In This Issue: Columns: Revealed At Last (Editorial Comments) ............................................2 Pulp Sources.....................................................................................2 Reviews Secret Agent X-9 on radio................................................................3 EFanzine Reviews............................................................................4 Slight of Hand #2 ............................................................................5 ROCURED Pulpgen Download Reviews......................................................... 6-7 The Men Who Made The Argosy P Captain A. E. Dingle.........................................................................8 Articles Recent Acquisitions.................................................................... 9-14 95404 CA, Santa Rosa, 1130 Fourth Street, #116 1130 Fourth Street, ASILY Corrections: E Corrections to Back Numbers, Issue Eight E Michelle Nolan’s name was misspelled in a photo caption last issue. I apologize for the error. B Warren HarrisWarren AN C UMBERS N ACK B Now with 50% less content: less withNow 50% Prepared for P.E.A.P.S. mailing #63 for P.E.A.P.S. Prepared October 2003 (707) 577-0522 Issue 9 [email protected] email: Back Numbers Our Second Anniversary Issue to recent political events not to run. This is going It’s hard for me to believe but with this issue we to be my only comment on the matter, however, start our third year of publication. I never thought I don’t want to ruin my zine by turning it into a I’d last more than six months doing this before I ran lengthy political rant. out of things to write about. Of course, the deadline is little more than a week Americans are considered crazy anywhere in the world. away, and I have only one page fi nished so this might They will usually concede a basis for the accusation but be a pretty thin issue. point to California as the focus of the infection. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

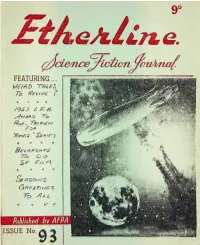

Etherline93.Pdf

9D Et/ieklin g. ETHEKLINE 3 v'//lili ALL GOOD UJISHES Fkk CHRiSimflS from the members of AMATEUR FANTASY PUBLICATIONS OP AUSTRALIA from the members of MELBOURNE SCIENCE FICTION CLUB Note: — The Melbourne Science Fiction Club will close after the meeting of Thursday December 19th., and re-open on Tuesday, January 7th. The next issue of ETHEPLINE will bear a publishing date of: January 23rd. THE LEADING, SCIENCE FICTION JOURNAL 4 IS SPACE OUR DESTINY ? ETHERLINE /S Space OwDest/ny ? Back in 1939, a young New Zealander, fresh from school, spent 5/- for two old ship's portholes and ground then into lenses for a giant telescope. While most of his ex-schoolmates were apply ing themselves to far less serious forms of relaxation, young Har vey Blanks was already an enthusiatic secretary of the Auckland As tronomical Society, and an avid reader of anything and everything vaguely connected with satellites, rockets or space. Night after night he was either building his telescope or 'on duty' at the society's observatory to which the curious Aucklanders went in their scores to peer up at the heavens. By the time he was 17, Harvey Blanks was something of an authority on space travel and the rest - and there ou have the background to his success as a writer of science fiction for radio. Last year, his serial CAPTAIN MIRACLE ran 208 instalments in three States, and now he has scored again with a first-rate script for adults, titled SPACE - OUR DESTINY. Behind this serial,is quite a story. Into it, Blanks has poured 18 years of acc umulated experience and more than a year of intensive research, in which time he haunted the- Public Library, read extensively and so sought information wherever it was to be found. -

Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Guides to Manuscript Collections Search Our Collections 2006 0749: Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006 Marshall University Special Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/sc_finding_aids Part of the Fiction Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Playwriting Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Nelson Slade Bond Collection, 1920-2006, Accession No. 2006/04.0749, Special Collections Department, Marshall University, Huntington, WV. This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Search Our Collections at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Guides to Manuscript Collections by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 0 REGISTER OF THE NELSON SLADE BOND COLLECTION Accession Number: 2006/04.749 Special Collections Department James E. Morrow Library Marshall University Huntington, West Virginia 2007 1 Special Collections Department James E. Morrow Library Marshall University Huntington, WV 25755-2060 Finding Aid for the Nelson Slade Bond Collection, ca.1920-2006 Accession Number: 2006/04.749 Processor: Gabe McKee Date Completed: February 2008 Location: Special Collections Department, Morrow Library, Room 217 and Nelson Bond Room Corporate Name: N/A Date: ca.1920-2006, bulk of content: 1935-1965 Extent: 54 linear ft. System of Arrangement: File arrangement is the original order imposed by Nelson Bond with small variations noted in the finding aid. The collection was a gift from Nelson S. Bond and his family in April of 2006 with other materials forwarded in May, September, and November of 2007. -

In the Beginning – a Very Abbreviated History of the Earliest Days of Science Fiction Fandom

In the Beginning – A Very Abbreviated History of the Earliest Days of Science Fiction Fandom by Rich Lynch The history of science fiction fandom in certain ways is not unlike the geological history of the Earth. Back in the earliest geological era, most of Earth’s land mass was combined into one super- continent, Pangaea. The earliest days of science fiction fandom were comparable, in that once there was a solitary fan group, the Science Fiction League (or SFL), that attempted to bring most of the science fiction fans together into a single organization. The SFL was created by publisher Hugo Gernsback in the May 1934 issue of Wonder Stories. Science fiction fandom was already in existence by then, but it mostly consisted of isolated individuals publishing fan magazines with one or two fan clubs existing in large population centers. This would soon change. That issue of Wonder sported the colorful emblem of the SFL on its cover: a wide-bodied multi-rocketed spaceship passing in front of the Earth. Inside, Gernsback’s four-page editorial summed up the SFL as an organization “for the furtherance and betterment of the art of science fiction” and implored fans to join the new organization and “spread the gospel of science fiction.” The response was almost immediate. Fans from various parts of the United States wrote enthusiastic letters, many of which were published by Gernsback in Wonder’s letters column. Some of the respondents started chapters of the SFL in various cities, and most of the science fiction clubs that already existed became affiliates of the SFL. -

American Comics Group

Ro yThomas’ Amer ican Comics Fanzine $6.95 In the USA No. 61 . s r e d August l o SPECIAL ISSUE! H 2006 t h g i r FABULOUS y MICHAEL VANCE’S p o C FULL-LENGTH HISTORY OF THE e v i t c e p s e R 6 0 AMERICAN 0 2 © & M T COMICS GROUP– s r e t c a r a h C STANDARD NEDO R STANDARD //NEDO R ; o n a d r o i G COOMMIICCSS – k c i D 6 & THE SANGOR ART SHOP! 0 0 2 © t -FEATURING YOUR FAVORITES- r A MESKIN • ROBINSON • SCHAFFENBERGER WILLIAMSON • FRAZETTA • MOLDOFF BUSCEMA • BRADBURY • STONE • BALD HARTLEY • COSTANZA • WHITNEY RICHARD HUGHES • & MORE!! 08 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 61 / August 2006 ™ Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editors Emeritus Jerry Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Production Assistant Eric Nolen-Weathington Cover Artist Dick Giordano Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko And Special Thanks to: Writer /Editorial: Truth, Justice, &The American (Comics Group) Way . 2 Heidi Amash Heritage Comics Dick Ayers Henry R. Kujawa Forbidden Adventures: The History Of The American Comics Group . 3 Dave Bennett Bill Leach Michael Vance’s acclaimed tome about ACG, Standard/Nedor, and the Sangor Shop! Jon Berk Don Mangus Daniel Best Scotty Moore “The Lord Gave Me The Opportunity To Do What I Wanted” . 75 Bill Black Matt Moring ACG/Timely/Archie artist talks to Jim Amash about his star-studded career. -

Science and Edgar Allan Poe's Pathway to Cosmic Truth

SCIENCE AND EDGAR ALLAN POE’S PATHWAY TO COSMIC TRUTH by Mo Li A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University May 2017 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Philip Edward Phillips, Chair Dr. Maria K. Bachman Dr. Harry Lee Poe I dedicate this study to my mother and grandmother. They taught me persistence and bravery. !ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I must express my immense gratitude to Dr. Philip Edward Phillips for opening up Edgar Allan Poe’s starry worlds to me. Without Dr. Phillips’s generous guidance and inestimable patience, I could not have completed this study. I would also like to thank Dr. Maria K. Bachman and Dr. Harry Lee Poe. Their invaluable insights and suggestions led me to new discoveries in Poe. !iii ABSTRACT Poe’s early grievance in “Sonnet—To Science” (1829) against science’s epistemological authority transitioned into a lifelong journey of increasingly fruitful maneuvering. Poe’s engagement with science reached its apogee in Eureka: A Prose Poem (1848), his cosmological and aesthetic treatise published near the end of his life. While exalting intuition and poetic imagination as the pathway to Truth, Eureka builds upon, questions, and revises a wealth of scientific authorities and astronomical works. Many classic and recent studies, however, appreciate the poetic value but overlook or reject the scientific significance of the treatise. In contrast, some scholars assess Eureka by its response and contribution to specific theories and methods of nineteenth-century or contemporary science. Although some scholars have defended Eureka’s scientific achievements, they rarely investigate the role of science in Poe’s other works, especially his early or enigmatic ones. -

Dealer Newsletter for the 44Th Great Summer Pulp Convention!

Dealer Newsletter for the 44th Great Summer Pulp Convention! PulpFest 2015, the popular summer convention for fans and We’ll have presentations on Wheeler-Nicholson and Standard’s collectors of vintage popular culture material, returns to the detective, western, sports, and pulp and comic book heroes. spectacular Hyatt Regency in Columbus, Ohio for its 44 th PulpFest is also delighted to feature a presentation by Philip M. edition. It will begin Thursday evening, August13 th, at 6 PM Sherman, the nephew of managing editor Leo Margulies, as and run through Sunday, August 16 th , at 2 PM. well as a discussion of the publisher’s editorial policies, featuring pulp historians Ed Hulse, editor and publisher of FarmerCon will be joining us for the fifth straight year for their Blood ‘n’ Thunder , and Will Murray, author of the acclaimed annual celebration of the life and works of Grand Master of series, The All-New Wild Adventures of Doc Savage . Science Fiction Philip José Farmer. To learn more about FarmerCon X , please visit the convention’s website at Additionally, the comic book line of leading pulp magazine http://pjfarmer.com/upcome.htm . publisher Street & Smith turns seventy-five years old in 2015. PulpFest will honor this occasion with a panel and slide-show Since 2009, PulpFest has annually drawn hundreds of fans and presentation on the subject offered by comic book scholars collectors of vintage popular fiction and related materials to Murray, former DC Comics colorist and Sanctum Books Columbus, Ohio where it is currently based. Although publisher Anthony Tollin, and Tony Isabella, a popular writer centered around pulp fiction and pulp magazines, PulpFest was and editor for both DC and Marvel Comics, as well as a founded on the premise that the pulps had a profound effect longtime columnist for the Comics Buyer's Guide . -

The Placement of Lucian's Novel True History in the Genre of Science Fiction

INTERLITT ERA RIA 2016, 21/1: 158–171 The Placement of Lucian’s Novel True History in the Genre of Science Fiction KATELIS VIGLAS Abstract. Among the works of the ancient Greek satirist Lucian of Samosata, well-known for his scathing and obscene irony, there is the novel True History. In this work Lucian, being in an intense satirical mood, intended to undermine the values of the classical world. Through a continuous parade of wonderful events, beings and situations as a substitute for the realistic approach to reality, he parodies the scientific knowledge, creating a literary model for the subsequent writers. Without doubt, nowadays, Lucian’s large influence on the history of literature has been highlighted. What is missing is pointing out the specific characteristics that would lead to the placement of True History at the starting point of Science Fiction. We are going to highlight two of these features: first, the operation of “cognitive estrangement”, which aims at providing the reader with the perception of the difference between the convention and the truth, and second, the use of strange innovations (“novum”) that verify the value of Lucian’s work by connecting it to historicity. Keywords: Lucian of Samosata; True History; satire; estrangement; “novum”; Science Fiction Introduction Initially, we are going to present a biography of Lucian in relation to the spirit of his era and some judgments on his work. Furthermore, we will proceed to a brief reference to the influences exerted by his novel True History on the history of literature, especially on the genre of Science Fiction. -

By Robert 'Bloch

NUMBER ONE, published April 15, 1959 for SAPS is edited by Earl Kemp and published with more than the normal amount of as sistance on the part of Jim O’Meara and Nancy Kemp, This first issue will be duplicated cn the JOE-JIM mimeograph, courtesy of Joe Sarno and the above ■, mentioned Jim O'Meara who is doing the bulk of the crank turning, SaFari is NOT for sale. Outside SAPS it will have to serve as a letter-sub stitute to the several people to whom I owe letters that will most probably never -hear from me otherwise, A very flattering picture of yours truly in a "beat" mood adorns the cover of this issued In the first place, I don't have that much hair any more. In the second place, I've shaved off the beard. I kept the mustache, and at least of this writing have started on the second attempt at a beard. The one you see ■'m the cover was three weeks old, and a real beaut, but I thought I'd look a little more normal without it, and as I had to impress the finance company as to what a respectable type person I was, in order to get a car, I shaved it Off. Much to my.sorrow. The picture was drawn by Shirley Porzio, my bongo instructor, P.Si, I also gave up the bongos. Beards are funny things, I'd just reached the point where everyone at work was resigned to the point of fact that I was going to wear it regardless of what they thought, when I shaved it off, and I've got that whole bit to play over again. -

THEN: Science Fiction Fandom in the UK 1930-1980

THEN Science Fiction Fandom in the UK: 1930-1980 This PDF sampler of THEN consists of the first 48 pages of the 454-page book – comprising the title and copyright pages, both introductions and the entire section devoted to the 1930s – plus the first two pages from the Source Notes, with all the 1930s notes. To read more about the whole book (available in hardback, trade paperback and ebook) please visit http://ae.ansible.uk/?t=then . Other Works by Rob Hansen The Story So Far ...: A Brief History of British Fandom (1987) THEN 1: The 1930s and 1940s (1988) THEN 2: The 1950s (1989) THEN 3: The 1960s (1991) THEN 4: The 1970s (1993) On the TAFF Trail (1994) THEN Science Fiction Fandom in the UK: 1930-1980 ROB HANSEN Ansible Editions • 2016 THEN Science Fiction Fandom in the UK: 1930-1980 FIRST BOOK PUBLICATION Published by Ansible Editions 94 London Road, Reading, England, RG1 5AU http://ae.ansible.uk Copyright © 2016 by Rob Hansen. Original appearances Copyright © 1987-1993 by Rob Hansen as described in “Acknowledgements” on page 427, which constitutes an extension of this copyright page. This Ansible Editions book published 2016. Printed and distributed by Lulu.com. The right of Rob Hansen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the Author in accordance with the British Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means, mechanical, electronic or otherwise, without first obtaining the permission of the copyright holder. Cover photograph: Convention hall and stage backdrop at BULLCON , the 1963 UK Eastercon held at the Bull Hotel in Peterborough. -

Member Newsletter for the 44Th Great Summer Pulp

Member Newsletter for the 44 th Great Summer Pulp Convention! PulpFest 2015, the popular summer convention for fans and the Black Bat and wrote many Phantom Detective, Candid collectors of vintage popular culture material, returns to the Camera Kid, and Masked Detective stories, and Thrilling spectacular Hyatt Regency in Columbus, Ohio for its 44 th publisher Ned Pines are 110; and Mort Weisinger, editor of edition. It will begin Thursday evening, August 13 th, at 6 PM Captain Future and other Thrilling magazines, as well as editor and run through Sunday, August 16 th , at 2 PM. of the Superman books for DC Comics, and Leigh Brackett and Henry Kuttner, both noted writers for Standard’s line of FarmerCon will be joining us for the fifth straight year for their science-fiction pulps, are 100 years old. That makes eight annual celebration of the life and works of Grand Master of reasons to salute Standard Magazines in 2015! Science Fiction Philip José Farmer. To learn more about FarmerCon X , please visit the convention’s website at We’ll have presentations on Wheeler-Nicholson and Standard’s http://pjfarmer.com/upcome.htm . detective, western, sports, and pulp and comic book heroes. PulpFest is also delighted to feature a presentation by Philip M. Since 2009, PulpFest has annually drawn hundreds of fans and Sherman, the nephew of managing editor Leo Margulies, as collectors of vintage popular fiction and related materials to well as a discussion of the publisher’s editorial policies, Columbus, Ohio where it is currently based. Although featuring pulp historians Ed Hulse, editor and publisher of centered around pulp fiction and pulp magazines, PulpFest was Blood ‘n’ Thunder , and Will Murray, writer of countless books founded on the premise that the pulps had a profound effect and articles on popular culture, as well as the author of the on American popular culture, reverberating through a wide acclaimed series, The All-New Wild Adventures of Doc Savage , variety of media—comic books, movies, paperbacks and genre published by Altus Press.