From Commonwealth to Constitutional Limitations: Thomas Cooley's Michigan, 1805-1886

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

This Constitution: a Bicentennial Chronicle, Nos. 14-18

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 300 290 SO 019 380 AUTHOR Mann, Shelia, Ed. TITLE This Constitution: A Bicentennial Chronicle, Nos. 14-18. INSTITUTION American Historical Association, Washington, D.C.; American Political Science Association, Washington, D.C.; Project '87, Washington, DC. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 87 NOTE 321p.; For related document, see ED 282 814. Some photographs may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROMProject '87, 1527 New Hampshire Ave., N.W., Washington, DC 20036 nos. 13-17 $4.00 each, no. 18 $6.00). PUB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) -- Historical Materials (060) -- Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) JOURNAL CIT This Constitution; n14-17 Spr Sum Win Fall 1987 n18 Spr-Sum 1988 EDRS PRICE MFO1 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *Constitutional History; *Constitutional Law; History Instruction; Instructioral Materials; Lesson Plans; Primary Sources; Resource Materials; Secondary Education; Social Studies; United States Government (Course); *United States History IDENTIFIERS *Bicentennial; *United States Constitution ABSTRACT Each issue in this bicentennial series features articles on selected U.S. Constitution topics, along with a section on primary documents and lesson plans or class activities. Issue 14 features: (1) "The Political Economy of tne Constitution" (K. Dolbeare; L. Medcalf); (2) "ANew Historical Whooper': Creating the Art of the Constitutional Sesquicentennial" (K. Marling); (3) "The Founding Fathers and the Right to Bear Arms: To Keep the People Duly Armed" (R. Shalhope); and (4)"The Founding Fathers and the Right to Bear Arms: A Well-Regulated Militia" (L. Cress). Selected articles from issue 15 include: (1) "The Origins of the Constitution" (G. -

X001132127.Pdf

' ' ., ,�- NONIMPORTATION AND THE SEARCH FOR ECONOMIC INDEPENDENCE IN VIRGINIA, 1765-1775 BRUCE ALLAN RAGSDALE Charlottesville, Virginia B.A., University of Virginia, 1974 M.A., University of Virginia, 1980 A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Corcoran Department of History University of Virginia May 1985 © Copyright by Bruce Allan Ragsdale All Rights Reserved May 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: 1 Chapter 1: Trade and Economic Development in Virginia, 1730-1775 13 Chapter 2: The Dilemma of the Great Planters 55 Chapter 3: An Imperial Crisis and the Origins of Commercial Resistance in Virginia 84 Chapter 4: The Nonimportation Association of 1769 and 1770 117 Chapter 5: The Slave Trade and Economic Reform 180 Chapter 6: Commercial Development and the Credit Crisis of 1772 218 Chapter 7: The Revival Of Commercial Resistance 275 Chapter 8: The Continental Association in Virginia 340 Bibliography: 397 Key to Abbreviations used in Endnotes WMQ William and Mary Quarterly VMHB Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Hening William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large; Being� Collection of all the Laws Qf Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature in the year 1619, 13 vols. Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia Rev. Va. Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, 7 vols. LC Library of Congress PRO Public Record Office, London co Colonial Office UVA Manuscripts Department, Alderman Library, University of Virginia VHS Virginia Historical Society VSL Virginia State Library Introduction Three times in the decade before the Revolution. Vir ginians organized nonimportation associations as a protest against specific legislation from the British Parliament. -

Constitution of Michigan of 1835

Constitution of Michigan of 1835 In convention, begun at the city of Detroit, on the second Monday of May, in the year one thousand eight hundred and thirty five: Preamble. We, the PEOPLE of the territory of Michigan, as established by the Act of Congress of the Eleventh day of January, in the year one thousand eight hundred and five, in conformity to the fifth article of the ordinance providing for the government of the territory of the United States, North West of the River Ohio, believing that the time has arrived when our present political condition ought to cease, and the right of self-government be asserted; and availing ourselves of that provision of the aforesaid ordinance of the congress of the United States of the thirteenth day of July, one thousand seven hundred and eighty-seven, and the acts of congress passed in accordance therewith, which entitle us to admission into the Union, upon a condition which has been fulfilled, do, by our delegates in convention assembled, mutually agree to form ourselves into a free and independent state, by the style and title of "The State of Michigan," and do ordain and establish the following constitution for the government of the same. ARTICLE I BILL OF RIGHTS Political power. First. All political power is inherent in the people. Right of the people. 2. Government is instituted for the protection, security, and benefit of the people; and they have the right at all times to alter or reform the same, and to abolish one form of government and establish another, whenever the public good requires it. -

Symbolism of Commander Isaac Hull's

Presentation Pieces in the Collection of the USS Constitution Museum Silver Urn Presented to Captain Isaac Hull, 1813 Prepared by Caitlin Anderson, 2010 © USS Constitution Museum 2010 What is it? [Silver urn presented to Capt. Isaac Hull. Thomas Fletcher & Sidney Gardiner. Philadelphia, 1813. Private Collection.](1787–1827) Silver; h. 29 1/2 When is it from? © USS Constitution Museum 2010 1813 Physical Characteristics: The urn (known as a vase when it was made)1 is 29.5 inches high, 22 inches wide, and 12 inches deep. It is made entirely of sterling silver. The workmanship exhibits a variety of techniques, including cast, applied, incised, chased, repoussé (hammered from behind), embossed, and engraved decorations.2 Its overall form is that of a Greek ceremonial urn, and it is decorated with various classical motifs, an engraved scene of the battle between the USS Constitution and the HMS Guerriere, and an inscription reading: The Citizens of Philadelphia, at a meeting convened on the 5th of Septr. 1812, voted/ this Urn, to be presented in their name to CAPTAIN ISAAC HULL, Commander of the/ United States Frigate Constitution, as a testimonial of their sense of his distinguished/ gallantry and conduct, in bringing to action, and subduing the British Frigate Guerriere,/ on the 19th day of August 1812, and of the eminent service he has rendered to his/ Country, by achieving, in the first naval conflict of the war, a most signal and decisive/ victory, over a foe that had till then challenged an unrivalled superiority on the/ ocean, and thus establishing the claim of our Navy to the affection and confidence/ of the Nation/ Engraved by W. -

Michigan Legal Studies Unreported Opinions of The

MICHIGAN LEGAL STUDIES UNREPORTED OPINIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT OF MICHIGAN 1836- 1843 PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN LAW SCHOOL WHICH, HOWEVER, ASSUMES NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE VIEWS EXPRESSED( WITH THE AID OF FUNDS DERIVED FROM GIFTS THE UNIVERSITY TO OF MICHIGAN) BY WILLIAM W. COOK. MICHIGAN LEGAL STUDIES Hessel E. Yntema, Editor DISCOVERY BEFORE TRIAL George Ragland, Jr. ToRTS IN THE CoNFLICT OF LAws Moffatt Hancock THE AMENDING oF THE FEDERAL CoNSTITUTION Lester B. Orfield REVIEW oF ADMINISTRATIVE AcTs Armin Uhler THE PREVENTION OF REPEATED CRIME John Barker Waite THE CoNFLICT oF LAws: A CoMPARATIVE STUDY Ernst Rabel UNREPORTED OPINIONS oF THE SuPREME CouRT oF MICHIGAN 1836-1843 William Wirt Blume, Editor UNREPORTED OPINIONS OF THE SUPREME COURT OF MICHIGAN 1836-1843 Edited by WILLIAM WIRT BLUME PROFESSOR OF LAW, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Foreword by H. WALTER NoRTH JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT OF MICHIGAN Historical Introduction by F. CLARK NoRTON INSTRUCTOR IN POLITICAL SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Ann Arbor THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS 194 5 CoPYRIGHT, 1945 BY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Foreword N July I8J6 final jurisdiction of non-federal litigation I passed from the Michigan Territorial Supreme Court to the Supreme Court of the State of Michigan. Then, substantially as now, the Constitution provided: "The judi cial power shall be vested in one supreme court, and such other courts as the legislature may from time to time estab lish." Mich. Const. I 835, Art. VI, §r. Those who are inter ested in the judicial history of Michigan prior to I 8 3 6 are fortunate in having access to much of such history contained in the six volumes entitled "Transactions of the Supreme Court of Michigan," edited by Professor William Wirt Blume of the Michigan Law School faculty. -

Amending and Revising State Constitutions J

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 35 | Issue 2 Article 2 1947 Amending and Revising State Constitutions J. E. Reeves University of Kentucky Kenneth E. Vanlandingham University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Reeves, J. E. and Vanlandingham, Kenneth E. (1947) "Amending and Revising State Constitutions," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 35 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol35/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMENDING AND REVISING STATE CONSTITUTIONS J. E. REEVES* and K-ENNETii E. VANLANDINGHAMt Considerable interest in state constitutional revision has been demonstrated recently. Missouri and Georgia adopted re- vised constitutions in 1945 and New Jersey voted down a pro- posed revision at the general election in 1944. The question of calling a constitutional convention was acted upon unfavorably by the Illinois legislature in May, 1945, and the Kentucky legis- lature, at its 1944 and 1946 sessions, passed a resolution submit- ting" the question of calling a constitutional convention to the people of the state who will vote upon it at the general election in 1947. The reason for this interest in revision is not difficult to detect. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT of MICHIGAN SOUTHERN DIVISION Russ Bellant, Detroit Library Commissioner

2:17-cv-13887-GCS-MKM Doc # 11 Filed 03/12/18 Pg 1 of 47 Pg ID 56 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN SOUTHERN DIVISION Russ Bellant, Detroit Library Commissioner; Tawanna Simpson, Lamar Lemmons, Detroit Public Schools Board Member; Elena Herrada; Kermit Williams, Pontiac City No. 2:17-cv-13887 Council Member; Donald Watkins; Duane Seats, Juanita Henry, and Mary Alice Adams, HON. GEORGE CARAM Benton Harbor Commissioners; William STEEH “Scott” Kincaid, Flint City Council President; Bishop Bernadel Jefferson; Paul Jordan; Rev. MAGISTRATE JUDGE Jim Holley, National Board Member Rainbow R. STEVEN WHALEN Push Coalition; Rev. Charles E. Williams II, Michigan Chairman, National Action Network; Rev. Dr. Michael A. Owens, Rev. Lawrence Glass, Rev. Dr. Deedee Coleman, DEFENDANTS’ MOTION TO Executive Board, Council of Baptist Pastors DISMISS of Detroit and Vicinity, Plaintiffs, v RICHARD D. SNYDER, as Governor of the State of Michigan; ANDREW DILLON, as the former Treasurer of the State of Michigan, R. KEVIN CLINTON as former Treasurer of the State of Michigan, and NICK KHOURI, as Treasurer of the State of Michigan, acting in their individual and/or official capacities, Defendants. Herbert A. Sanders (P43031) John C. Philo (P52721) The Sanders Law Firm PC Anthony D. Paris (P71525) Attorney for Plaintiffs Sugar Law Center 615 Griswold St., Ste. 913 Attorneys for Plaintiffs Detroit, Michigan 48226 4605 Cass Ave., 2nd Floor 313.962.0099 Detroit, Michigan 48201 [email protected] 313.993.4505 2:17-cv-13887-GCS-MKM Doc # 11 Filed 03/12/18 Pg 2 of 47 Pg ID 57 Julie H. -

Supreme Court

THE SUPREME COURT MAURA D. CORRIGAN, CHIEF JUSTICE State Court Administrative Office P.O. Box 30048, Lansing, MI 48909 Phone: (517) 373-0130 Under the territorial government of Michigan established in 1805, the supreme court consisted of a chief judge and 2 associate judges appointed by the President of the United States. Under the “second” grade of territorial government established in 1824, the term of office was limited to 4 years. First Grade Augustus B. Woodward . 1805-1824 James Witherell . 1805-1824 Frederick Bates . 1805-1808 John Griffin . 1806-1824 Second Grade James Witherell . 1824-1828 William Woodbridge . 1828-1832 John Hunt . 1824-1827 George Morrell . 1832-1837 Solomon Sibley . 1824-1837 Ross Wilkins . 1832-1837 Henry Chipman . 1827-1832 The Constitution of 1835 provided for a supreme court, the judges of which were appointed by the governor, by and with the advice and consent of the senate, for 7-year terms. In 1836 the legislature provided for a chief justice and 2 associate justices. The state was then divided into 3 circuits and the supreme court was required to hold an annual term in each circuit. The Revised Statutes of 1838 provided for a chief justice and 3 associate justices. The Constitution of 1850 provided for a term of 6 years and that the judges of the 5 circuit courts be judges of the supreme court. In 1857, the legislature reorganized the supreme court to consist of a chief justice and 3 associate justices to be elected for 8-year terms. The number of justices was increased to 5 by the legislature in 1887. -

Significance of the Battle of Detroit in August, 1812

War of 1812, Historical Thinking Project Lessons (Hux), Lesson 19 How Historically Significant was the 1812 Battle of Detroit? By Allan Hux Suggested grade level: intermediate / senior Suggested time: up to 2 periods Brief Description of the Task Students consider the circumstances that led to the Battle of Detroit and its dramatic outcome using group role-playing strategies. Historical Thinking Concepts • Historical Perspective-Taking • Historical Significance • Use of Evidence (primary and secondary) Learning Goals Students will: 1. Explore the different perspectives of First Nations, Great Britain, the colonists in Upper Canada, and the U.S.A. 2. Recognize the importance of the First Nations alliance with the British. 3. Examine the historical significance of the Battle of Detroit in August, 1812. Materials Photocopies of handouts. Masking tape, chalk, twine or string to create outline map of Upper Canada on the floor. Prior Knowledge It would be an asset for students to: • recognize some of the major causes and events leading up to the outbreak of the War of 1812 War of 1812, Historical Thinking Project Lessons (Hux), Lesson 19 Assessment • Individual student contributions to group work and group performance and a group Tableau. • Teacher feedback to groups. • Individual reflections on learning. Detailed Lesson Plan Focus Question: How significant was the British and First Nations victory at Detroit in July-August 1812? 1. Display a map of Upper and Lower Canada and the Ohio Country prior to the War of 1812 and have the students identify the areas of Canadian, First Nations and American settlement. See Appendix 1: Map of the Canadas and the Ohio Country.) 2. -

The Judicial Branch

Chapter V THE JUDICIAL BRANCH The Judicial Branch . 341 The Supreme Court . 342 The Court of Appeals . 353 Michigan Trial Courts . 365 Judicial Branch Agencies . 381 2013– 2014 ORGANIZATION OF THE JUDICIAL BRANCH Supreme Court 7 Justices State Court Administrative Office Court of Appeals (4 Districts) 28 Judges Circuit Court Court of Claims (57 Circuits) Hears claims against the 218 Judges State. This is a function of General Jurisdiction the 30th Judicial Circuit Court, includes Court (Ingham County). Family Division Probate District Court Municipal Court (78 Courts) (104 Districts) (4 Courts) 103 Judges 248 Judges 4 Judges Certain types of cases may be appealed directly to the Court of Appeals. The Constitution of the State of Michigan of 1963 provides that “The judicial power of the state is vested exclusively in one court of justice which shall be divided into one supreme court, one court of appeals, one trial court of general jurisdiction known as the circuit court, one probate court, and courts of limited jurisdiction that the legislature may establish by a two-thirds vote of the members elected to and serving in each house.” Michigan Manual 2013 -2014 Chapter V – THE JUDICIAL BRANCH • 341 THE SUPREME COURT JUSTICES OF THE MICHIGAN SUPREME COURT Term expires ROBERT P. YOUNG, JR., Chief Justice . Jan. 1, 2019 MICHAEL F. CAVANAGH . Jan. 1, 2015 MARY BETH KELLY . Jan. 1, 2019 STEPHEN J. MARKMAN . Jan. 1, 2021 BRIDGET MARY MCCORMACK . Jan. 1, 2021 DAVID F. VIVIANO . Jan. 1, 2015 BRIAN K. ZAHRA . Jan. 1, 2015 www.courts.mi.gov/supremecourt History Under the territorial government of Michigan established in 1805, the supreme court consisted of a chief judge and two associate judges appointed by the President of the United States. -

OAG Annual Report 2006

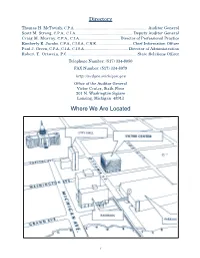

Directory Thomas H. McTavish, C.P.A. ........................................................................ Auditor General Scott M. Strong, C.P.A., C.I.A. ........................................................ Deputy Auditor General Craig M. Murray, C.P.A., C.I.A. ....................................... Director of Professional Practice Kimberly E. Jacobs, C.P.A., C.I.S.A., C.N.E. ...................................Chief Information Officer Paul J. Green, C.P.A., C.I.A., C.I.S.A. ........................................... Director of Administration Robert T. Ortwein, P.C...................................................................... State Relations Officer Telephone Number: (517) 334-8050 FAX Number: (517) 334-8079 http://audgen.michigan.gov Office of the Auditor General Victor Center, Sixth Floor 201 N. Washington Square Lansing, Michigan 48913 Where We Are Located i STATE OF MICHIGAN OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL 201 N. WASHINGTON SQUARE LANSING, MICHIGAN 48913 (517) 334-8050 THOMAS H. MCTAVISH, C.P.A. FAX (517) 334-8079 AUDITOR GENERAL September 30, 2006 The Honorable Jennifer M. Granholm, Governor of Michigan The Honorable Kenneth R. Sikkema, Senate Majority Leader The Honorable Craig M. DeRoche, Speaker of the House The Honorable Robert L. Emerson, Senate Minority Leader The Honorable Dianne Y. Byrum, House Minority Leader and Members of the 93rd Legislature Ladies and Gentlemen: This annual report on the operations of the Michigan Office of the Auditor General covers the fiscal year ended September 30, 2006 and is submitted in accordance with Article IV, Section 53 of the State Constitution. The Office of the Auditor General has the responsibility, as stated in Article IV, Section 53 of the State Constitution, to conduct post financial and performance audits of State government operations. In addition, certain sections of the Michigan Compiled Laws contain specific audit requirements in conformance with the constitutional mandate.