Fasting Buddhas, Lalitavistara, and Karuṇāpuṇḍarīka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11.7 Vimutti Email July 2011

Enraptured with lust (raga), enraged with anger (dosa), blinded by delusion (moha), overwhelmed, with mind ensnared, people aim at their own ruin, at the ruin of others, at the ruin of both, and they experience mental pain and grief. But if lust, anger and delusion are given up, one aims neither at ones own ruin nor the ruin of others, and one experiences no mental pain and grief. This is Nibbana visible in this life, immediate, inviting, attractive and comprehensible to the wise. The Buddha A 3.55 News from Vimutti Monastery The 2011 rains retreat (i.e. the retreat in the rainy season) has now begun, and the Sangha members are dedicating themselves even more wholeheartedly to developing samadhi and insight. All major work projects and most external commitments have been set down for these three months. This is the time to appreciate and make the most of the tranquillity and silence of our forest monastery. Anyone who wishes to take part in the rains retreat can contact Venerable Mudito to reserve accommodation. In the month of June, Ajahn Chandako was in the U.S., teaching and seeing family and friends. He visited the Sangha at Abhayagiri Monastery in California and met with Vipassana teachers in the San Francisco area. A retreat was held in the seclusion of northern Minnesota, and the talks from that are available on the Vimutti website. On June 28 a Thai monk, Ajahn Nandhawat, arrived to join the Vimutti Sangha. He is a disciple of Luang Por Liem and Luang Por Piek and has been ordained 18 years. -

INDIAN FICTION – Classical Period Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D

INDIAN FICTION – Classical Period Stuart Blackburn, Ph.D. Overview ‘Moral story’ Short didactic tales known as nithi katha (‘moral story’) are generally in prose, although sometimes the ‘lesson’ itself is in verse. Nearly all these numerous stories began as oral tales before being collected and written down in manuscripts by scribes and scholars. The collections often use what is called a ‘frame-story’ to give a narrative coherence to the otherwise disparate tales. These originally oral tales were collected and redacted in manuscript form sometime in the early centuries of the Common Era. Some were composed in Pali, but most were in Sanskrit, although all were eventually written down in every Indian language. Oral tales Nearly every genre of ancient and classical Indian literature, from the Vedic hymns to the great epics, is founded on oral tradition and then mediated, and usually altered, through scribes and manuscripts. In the case of the collections of classical fiction, however, we see a more transparent process in which oral tradition was more completely replicated in written manuscripts. We cannot overstate the popularity and longevity of oral storytelling in India, nor can we put a date on it. We can only assume that the oral stories found in these classical story collections draw upon tales that, even by the time they were committed to writing in the 6th c. CE, were already hundreds of years old. Pancatantra Contents The Pancatantra (‘Five-Books’) is a collection of nearly 100 animal fables. The frame-story is that a pundit instructs three ignorant princes in the art of statecraft, using these moral stories as lessons. -

Mazdaism Text.Pdf

3 COTENTS. Address ... ... ... ... i-iv Foreword ... ... ... ... i — Abbreviations ... ... ... 4 Discourse 1 ... ... ... ... 5—83 Preliminaries 5. Zend-Avesta 9. Aliiira Mazda 10. Zoroastrian Duality 13. Unity of Godliood and Evil 22. Zatvan Akarana 23. Trinity, etc. 24. Fire 29. Naojotae Ceremony 37. Patet 38. —Theisms 42. Ethics 44. Motherhood of G<^ 51. Origin of Ideas 53. Christian In- debtedness 58. Moslem Indebtedness 59. Vishnuism and Mazdaism 61. Bhago-bakhta 65. Aramati67. Compara- tive Names, First List 68. Vaikuntha 69. Kaka-Sparsa 70. Reconcilation 74. Apology 76. ’Note A: Aryama Vaeja 78. Note B : Manu 78. Note C : Kine 79. Note D: Krishna, Blue 81. Note E : Morality 82. Note F: Vishnuism spreading 83. Discourse 11 ... ... ... 84— 138 Preliminary 84. Zend Avesta 84. Zaralhustra 86. Krishna 90. Daena 92. Ahura Mazda 94. AramStiti 97 Narayana loi. Comparative Names, Second List 102. Garodemana 104. Dakhma 108. Amesha Spentas no. Vishvaksena (Srosh) 113. Palingenesis 114. Parallelisms lao. ^ Archa or Symbolic Worship 121. Eschatology 123. Druj 129. Saosbyants 131. Universal Religion 133. Note A: Zarathustra 148. Note B: Ahura Mazda 152. Note C and D : Service is the End for all 159. Discourse III ... ... 159—219 Preliminary 159. The Triple Alliance 159. Caste and Class 162. Racial Affinities 164. Spenta 166. Time and Space 167. Ardvisura Anahita 169. The Quintuple Hy- postasis 171. Narasimha 173. The Farvardin Vast 174. Common Names, Third List 176. R^ma, Mitra, Vayu 178. Varaha, Vrishni, Akriira 181. Nar&yana, Raivata 182. Krishna 183. Ashi Vanguhi 188. Jarasandha, Gopi-Vasu 194. Astavatareta 195. Fravashi 197. Mantras 198. Gomez 211. Summing up 213. -

The Practice of Fasting After Midday in Contemporary Chinese Nunneries

The Practice of Fasting after Midday in Contemporary Chinese Nunneries Tzu-Lung Chiu University of Ghent According to monastic disciplinary texts, Buddhist monastic members are prohibited from eating solid food after midday. This rule has given rise to much debate, past and present, particularly between Mahāyāna and Theravāda Buddhist communities. This article explores Chinese Buddhist nuns’ attitudes toward the rule about not eating after noon, and its enforcement in contemporary monastic institutions in Taiwan and Mainland China. It goes on to investigate the external factors that may have influenced the way the rule is observed, and brings to light a diversity of opinions on the applicability of the rule as it has been shaped by socio- cultural contexts, including nuns’ adaptation to the locals’ ethos in today’s Taiwan and Mainland China. Introduction Food plays a pivotal role in the life of every human being, as the medium for the body’s basic needs and health, and is closely intertwined with most other aspects of living. As aptly put by Roel Sterckx (2005:1), the bio-cultural relationship of humans to eating and food “is now firmly implanted as a valuable tool to explore aspects of a society’s social, political and religious make up.” In the . 5(11): 57–89. ©5 Tzu-Lung Chiu THE Practice of FastinG AFTER MiddaY IN ContemporarY Chinese NUNNERIES realm of food and religion, food control and diet prohibitions exist in different forms in many world faiths. According to Émile Durkheim (1915:306), “[i]n general, all acts characteristic of the ordinary life are forbidden while those of the religious life are taking place. -

Satipaṭṭhāna Meditation: a Practice Guide

Praise for Satipaṭṭhāna Meditation: A Practice Guide This is a pearl of a book. On reading it, and comparing it to the author’s previous two studies of satipaṭṭhāna, the impression is that of having left the university lecture theatre and entered the meditation hall, where the wise and experienced teacher is offering Dhamma reflections, illuminating the practice of satipaṭṭhāna with a fertile and colourful lucidity, free of footnotes and arcane cross-references. This book is a treasure-house of practical teachings, rendered accessible with a clear and simple eloquence. The author states that his motivation has been to enrich the practice of satipaṭṭhāna rather than to compete with other approaches – he has succeeded admirably in this, I feel, and with praiseworthy skill and grace. – Ajahn Amaro This breathtaking practice guide is brief, and profound! It offers a detailed, engaging, and flexible approach to satipaṭṭhāna meditation that can be easily applied both in meditation and in day-to-day activities. The inspired practice suggestions and joyful enquiry that pervade each chapter will draw students, gradually but surely, towards deep liberating insight. Satipaṭṭhāna Meditation: A Practice Guide is destined to become an invaluable resource for meditators! – Shaila Catherine, author of Focused and Fearless: A Meditator’s Guide to States of Deep Joy, Calm, and Clarity Once more Bhikkhu Anālayo has written a masterpiece that holds within it an accessible and clear guide to developing and applying the teachings held within the Satipaṭṭhāna-sutta. Within this book Anālayo explores the subtle nuances of developing mindfulness and how that dedicated cultivation leads to the awakening pointed to in the discourse. -

How to Do Prostration by Sakya Pandita

How to do prostration By Sakya Pandita NAMO MANJUSHRIYE NAMO SUSHIRIYE NAMA UTAMA SHIRIYE SVAHA NAMO GURU BHYE NAMO BUDDHA YA NAMO DHARMA YA NAMO SANGHA YA By offering prostrations toward the exalted Three Jewels, may I and all sentient beings be purified of our negativities and obscurations. Folding the two hands evenly, may we attain the integration of method and wisdom. Placing folded hands on the crown, may we be born in the exalted pure realm of Sukhavati. Placing folded hands at the forehead, may we purify all negative deeds and obscurations of the body. Placing folded hands at the throat, may we purify all negative deeds and obscurations of the voice. Placing folded hands at the heart, may we purify all negative deeds and obscurations of the mind. Separating the folded hands, may we be able to perform the benefit of beings through the two rupakaya. Touching the two knees to the floor, may we gradually travel the five paths and ten stages. Placing the forehead upon the ground, may we attain the eleventh stage of perpetual radiance. Bending and stretching the four limbs, may we spontaneously accomplish the four holy activities of peace, increase, magnetizing, and subjugation of negative forces. Bending and stretching all veins and channels, may we untie the vein knots. Straightening and stretching the backbone and central channel, may we be able to insert all airs without exception into the central channel. Rising from the floor, may we be able to attain liberation by not abiding in samsara. 1 Repeatedly offering this prostration many times, may we be able to rescue sentient beings by not abiding in peace. -

The Teaching of Buddha”

THE TEACHING OF BUDDHA WHEEL OF DHARMA The Wheel of Dharma is the translation of the Sanskrit word, “Dharmacakra.” Similar to the wheel of a cart that keeps revolving, it symbolizes the Buddha’s teaching as it continues to be spread widely and endlessly. The eight spokes of the wheel represent the Noble Eightfold Path of Buddhism, the most important Way of Practice. The Noble Eightfold Path refers to right view, right thought, right speech, right behavior, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right meditation. In the olden days before statues and other images of the Buddha were made, this Wheel of Dharma served as the object of worship. At the present time, the Wheel is used internationally as the common symbol of Buddhism. Copyright © 1962, 1972, 2005 by BUKKYO DENDO KYOKAI Any part of this book may be quoted without permission. We only ask that Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai, Tokyo, be credited and that a copy of the publication sent to us. Thank you. BUKKYO DENDO KYOKAI (Society for the Promotion of Buddhism) 3-14, Shiba 4-chome, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan, 108-0014 Phone: (03) 3455-5851 Fax: (03) 3798-2758 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.bdk.or.jp Four hundred & seventy-second Printing, 2019 Free Distribution. NOT for sale Printed Only for India and Nepal. Printed by Kosaido Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan Buddha’s Wisdom is broad as the ocean and His Spirit is full of great Compassion. Buddha has no form but manifests Himself in Exquisiteness and leads us with His whole heart of Compassion. -

Reclaiming Buddhist Sites in Modern India: Pilgrimage and Tourism in Sarnath and Bodhgaya

RECLAIMING BUDDHIST SITES IN MODERN INDIA: PILGRIMAGE AND TOURISM IN SARNATH AND BODHGAYA RUTIKA GANDHI Bachelor of Arts, University of Lethbridge, 2014 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Religious Studies University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA ©Rutika Gandhi, 2018 RECLAIMING BUDDHIST SITES IN MODERN INDIA: PILGRIMAGE AND TOURISM IN SARNATH AND BODHGAYA RUTIKA GANDHI Date of Defence: August 23, 2018 Dr. John Harding Associate Professor Ph.D. Supervisor Dr. Hillary Rodrigues Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. James MacKenzie Associate Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. James Linville Associate Professor Ph.D. Chair, Thesis Examination Committee Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my beloved mummy and papa, I am grateful to my parents for being so understanding and supportive throughout this journey. iii Abstract The promotion of Buddhist pilgrimage sites by the Government of India and the Ministry of Tourism has accelerated since the launch of the Incredible India Campaign in 2002. This thesis focuses on two sites, Sarnath and Bodhgaya, which have been subject to contestations that precede the nation-state’s efforts at gaining economic revenue. The Hindu-Buddhist dispute over the Buddha’s image, the Saivite occupation of the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodhgaya, and Anagarika Dharmapala’s attempts at reclaiming several Buddhist sites in India have led to conflicting views, motivations, and interpretations. For the purpose of this thesis, I identify the primary national and transnational stakeholders who have contributed to differing views about the sacred geography of Buddhism in India. -

Agnihotra-Rituals-FINAL Copy

Agnihotra Rituals in Nepal The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Witzel, Michael. 2015. "Agnihotra Rituals in Nepal." In Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée, eds. Richard K. Payne and Michael Witzel, 371. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199351572.003.0014 Published Version doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199351572.003.0014 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:34391774 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Michael Witzel AGNIHOTRA RITUALS IN NEPAL Five* groups of Brahmins reside in the Kathmandu Valley of today:1 the Newari speaking Rājopādhyāya, the Nepali speaking Pūrbe, who immigrated in the last centuries before and the Gorkha conquest (1768/9 CE), the Kumaĩ, the Newari and Maithili speaking Maithila, and the Bhaṭṭas from South India, who serve at the Paśupatināth temple. Except for the Bhaṭṭas, all are followers of the White Yajurveda in its Mādhyandina recension. It could therefore be expected that all these groups, with the exception of the Bhaṭṭas, would show deviations from each other in language and certain customs brought from their respective homelands, but that they would agree in their (Vedic) ritual. However, this is far from being the case. On the contrary, the Brahmins of the Kathmandu Valley, who have immigrated over the last fifteen hundred years in several waves,2 constitute a perfect example of individual regional developments in this border area of medieval Indian culture, as well as of the successive, if fluctuating, influence of the ‘great tradition’ of Northern India. -

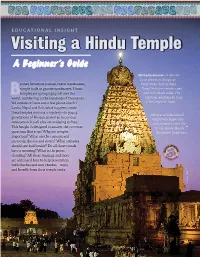

Visiting a Hindu Temple

EDUCATIONAL INSIGHT Visiting a Hindu Temple A Beginner’s Guide Brihadeeswarar: A massive stone temple in Thanjavur, e they luxurious palaces, rustic warehouses, Tamil Nadu, built by Raja simple halls or granite sanctuaries, Hindu Raja Chola ten centuries ago B temples are springing up all over the and still vibrant today. The world, numbering in the hundreds of thousands. capstone, weighing 80 tons, Yet outside of India and a few places like Sri is the largest in India. Lanka, Nepal and Bali, what happens inside these temples remains a mystery—to young This special Educational generations of Hindus as well as to curious Insight was inspired by newcomers. It’s all a bit intimidating at first. and produced expressly This Insight is designed to answer the common for the Hindu Mandir questions that arise: Why are temples Executives’ Conference important? What are the customs and protocols, the dos and don’ts? What attitudes should one hold inside? Do all those rituals ATI O C N U A D have a meaning? What is the priest L E chanting? All these musings and more I N S S T are addressed here to help newcomers— I G H both Hindus and non-Hindus—enjoy and benefit from their temple visits. dinodia.com Quick Start… Dress modestly, no shorts or short skirts. Remove shoes before entering. Be respectful of God and the Gods. Bring your problems, prayers or sorrows but leave food and improper manners outside. Do not enter the shrines without invitation or sit with your feet pointing toward the Deities or another person. -

Ancient Bacterian Bronze Age Fire Worship

CURRENT RESEARCH JOURNAL OF HISTORY 2(5): 71-77, May 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.37547/history-crjh-02-05-17 ISSN 2767-472X ©2021 Master Journals Accepted 25th May, 2021 & Published 31th May, 2021 ANCIENT BACTERIAN BRONZE AGE FIRE WORSHIP Komil Akramovich Rakhimov National Center Of Archeology Academy Of Sciences Of The Republic Of Uzbekistan ABSTRACT This article gives a brief overview of the results of research on the monuments of the Sopolli culture in northern Bactria, as well as the origin, shape, size, functions, stages of development, geography of distribution, geography of other cultures. comparisons with the findings of the eneolithic and Bronze Ages and comments on their periodic dates. It has also been scientifically substantiated that double-fire fire- worshiping furnaces in the eneolithic period continued as a tradition in later periods, i.e. in the Bronze Age, and that these furnaces were observed not in centralized temples but in family houses. KEYWORDS: - Ancient Bactria, Eneolithic, Chopontepa, Geoksyur, Altyndepe, Sapalli, Jarqo'ton, Dashly, Gonur-depe, Yassitepa, Chakmakli, Pessedjik, Togolok, Keleli, altar, fire, hearth, temple 1999]. At the same time, Zoroastrians base their INTRODUCTION beliefs on the struggle between two gods. Ahuramazda is a symbol of goodness, Ahriman is Furnaces found in the Stone Age sites were not a symbol of evil. The fire, which is a symbol of only for food processing, but also for the creation salvation, is supposedly created by Ahuramazda, of comfortable living conditions, but also as a and the fire serves as a reliable tool in the fight socio-cultural center that reflected the economic, against the giant Ahriman. -

Understanding Kalachakra Empowerment and Lineage

Understanding Kalachakra empowerment and lineage A Kalachakra initiation requires months of planning and preparation and the services of hundreds of monks, lay people and volunteers. It is one of the most elaborate and costly ($5 million, Washington 2011) blessing ceremonies in Buddhism. Regardless of the enormous effort required, His Holiness the Dalai Lama has given the Kalachakra initiation thirty one times throughout the world and preparations have been underway for a year for the next initiation in Bodhgaya, India (in December) where five to six hundred thousand people are expected to attend. Of the millions of people who have received or attended Kalachakra initiations it is doubtful that many have questioned the true origins, lineage, meaning and relevance of this high tantric teaching. As such, I write this article to explore: 1. a basic definition of Kalachakra 2. why His Holiness the Dalai Lama may choose to give Kalachakra empowerments so often given its cost and complexity 3. the main purpose of receiving Kalachakra initiation 4. if receiving Kalachakra initiation provides an opportunity to pursue the sublime tantric path further 5. after receiving the Kalachakra initiation, who is qualified to guide you on the sublime tantric path The word Kalachakra has a rich, complex definition that is too extensive for an article such as this, however it is possible to provide a basic overview. Kalachakra, a Sanskrit word, literally translates to kala meaning time and chakra meaning wheel, together a simple definition could be ultimate wheel of time. Another way to define Kalachakra briefly is the three Kalachakras: external Kalachakra (outer universe: all phenomena), internal Kalachakra (inner universe: body, speech and mind) and other Kalachakra (other universe: enlightened universe).