Race and Criminal Justice in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gladue Primer Is a Publication of the Legal Services Society (LSS), a Non-Government Organization That Provides Legal Aid to British Columbians

February 2011 © 2011 Legal Services Society, BC ISSN 1925-5799 (print) ISSN 1925-6140 (online) Acknowledgements Writer/Editor: Jay Istvanffy Designer: Dan Daulby Legal reviewer: Pamela Shields This booklet may not be commercially reproduced, but copying for other purposes, with credit, is encouraged. The Gladue Primer is a publication of the Legal Services Society (LSS), a non-government organization that provides legal aid to British Columbians. LSS is funded primarily by the provincial government and also receives grants from the Law Foundation and the Notary Foundation. This booklet explains the law in general. It isn’t intended to give you legal advice on your particular problem. Because each person’s case is different, you may need to get legal help. The Gladue Primer is up to date as of February 2011. Special thanks to Jonathan Rudin of Aboriginal Legal Services of Toronto and Linda Rainaldi for their contributions to this booklet. We gratefully acknowledge Community Legal Education Ontario (CLEO) for the use of the information in their booklet Are you Aboriginal? Do you have a bail hearing? Or are you going to be sentenced for a crime? (2009). How to get the Gladue Primer Get free copies of this booklet from your local legal aid office. Read online (in PDF) at www.legalaid.bc.ca/publications Order online: www.crownpub.bc.ca (click the Legal Services Society image) Phone: 1-800-663-6105 (call no charge) 250-387-6409 (Victoria) Fax: 250-387-1120 Mail: Crown Publications PO Box 9452 Stn Prov Govt Victoria, BC V8W 9V7 Contents Section -

Measuring Correctional Admissions of Aboriginal Offenders in Canada: a Relative Inter-Jurisdictional Analysis

Measuring Correctional Admissions of Aboriginal Offenders in Canada: A Relative Inter-jurisdictional Analysis ANDREW A REID Il est bien connu que les peuples autochtones sont surreprésentés dans le système de justice pénale canadien. Un examen des statistiques récentes qui documentent l’ampleur de cette surreprésentation dans la population condamnée à la détention au Canada, a mené la Commission de vérité et réconciliation à demander aux gouvernements fédéral, provinciaux et territoriaux d’agir. Afin de se préparer à répondre à ces « appels à l’action » de la Commission, il est important d’avoir de l’information de base complète qui servira à mesurer le progrès à l’avenir. Au-delà des statistiques de base qui documentent la surincarcération, peu de recherche explore les dynamiques de représentation des personnes contrevenantes autochtones dans d’autres parties du système correctionnel. Il n’en demeure pas moins qu’il s’agit d’un domaine d’étude important. Le nombre d’admissions à la détention est souvent utilisé pour décrire le problème de surreprésentation. Par ailleurs, les sanctions communautaires telles que la peine d’emprisonnement avec sursis et la probation sont perçues comme des alternatives positives à la détention. La présente étude utilise différentes techniques des mesures pour documenter les dynamiques récentes d’admission de personnes contrevenantes autochtones à ces trois parties des systèmes correctionnels provinciaux et territoriaux. Bien que les mesures habituelles telles que le dénombrement et le pourcentage soient utiles pour rendre compte d’un seul type d’admission, elles sont moins efficaces pour en comparer plusieurs, dans différentes juridictions. Nous considérons une autre technique des mesures plus utile pour ce genre d’enquête. -

Race and Drugs Oxford Handbooks Online

Race and Drugs Oxford Handbooks Online Race and Drugs Jamie Fellner Subject: Criminology and Criminal Justice, Race, Ethnicity, and Crime, Drugs and Crime Online Publication Date: Oct 2013 DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199859016.013.007 Abstract and Keywords Blacks are arrested on drug charges at more than three times the rate of whites and are sent to prison for drug convictions at ten times the white rate. These disparities cannot be explained by racial patterns of drug crime. They reflect law enforcement decisions to concentrate resources in low income minority neighborhoods. They also reflect deep-rooted racialized concerns, beliefs, and attitudes that shape the nation’s understanding of the “drug problem” and skew the policies chosen to respond to it. Even absent conscious racism in anti-drug policies and practices, “race matters.” The persistence of a war on drugs that disproportionately burdens black Americans testifies to the persistence of structural racism; drug policies are inextricably connected to white efforts to maintain their dominant position in the country’s social hierarchy. Without proof of racist intent, however, US courts can do little. International human rights law, in contrast, call for the elimination of all racial discrimination, even if unaccompanied by racist intent. Keywords: race, drugs, discrimination, arrests, incarceration, structural racism Millions of people have been arrested and incarcerated on drug charges in the past 30 years as part of America’s “war on drugs.” There are reasons to question the benefits—or even rationality—of that effort: the expenditure of hundreds of billions of dollars has done little to prevent illegal drugs from reaching those who want them, has had scant impact on consumer demand, has led to the undermining of many constitutional rights, and has helped produce a large, counterproductive, and expensive prison system. -

Overview of Race and Crime, We Must First Set the Parameters of the Discussion, Which Include Relevant Definitions and the Scope of Our Review

Overview CHAPTER 1 of Race and Crime Because skin color is socially constructed, it can also be reconstructed. Thus, when the descendants of the European immigrants began to move up economically and socially, their skins apparently began to look lighter to the whites who had come to America before them. When enough of these descendants became visibly middle class, their skin was seen as fully white. The biological skin color of the second and third generations had not changed, but it was socially blanched or whitened. —Herbert J. Gans (2005) t a time when the United States is more diverse than ever, with the minority popula- tion topping 100 million (one in every three U.S. residents; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010), the notion of race seems to permeate almost every facet of American life. A Certainly, one of the more highly charged aspects of the race dialogue relates to crime. Before embarking on an overview of race and crime, we must first set the parameters of the discussion, which include relevant definitions and the scope of our review. When speaking of race, it is always important to remind readers of the history of the concept and some current definitions. The idea of race originated 5,000 years ago in India, but it was also prevalent among the Chinese, Egyptians, and Jews (Gossett, 1963). Although François Bernier (1625–1688) is usually credited with first classifying humans into distinct races, Carolus Linnaeus (1707–1778) invented the first system of categorizing plants and humans. It was, however, Johan Frederich Blumenbach (1752–1840) who developed the first taxonomy of race. -

Explaining the Gaps in White, Black, and Hispanic Violence Since 1990

ASRXXX10.1177/0003122416635667American Sociological ReviewLight and Ulmer 6356672016 American Sociological Review 2016, Vol. 81(2) 290 –315 Explaining the Gaps in White, © American Sociological Association 2016 DOI: 10.1177/0003122416635667 Black, and Hispanic Violence http://asr.sagepub.com since 1990: Accounting for Immigration, Incarceration, and Inequality Michael T. Lighta and Jeffery T. Ulmerb Abstract While group differences in violence have long been a key focus of sociological inquiry, we know comparatively little about the trends in criminal violence for whites, blacks, and Hispanics in recent decades. Combining geocoded death records with multiple data sources to capture the socioeconomic, demographic, and legal context of 131 of the largest metropolitan areas in the United States, this article examines the trends in racial/ethnic inequality in homicide rates since 1990. In addition to exploring long-established explanations (e.g., disadvantage), we also investigate how three of the most significant societal changes over the past 20 years, namely, rapid immigration, mass incarceration, and rising wealth inequality affect racial/ ethnic homicide gaps. Across all three comparisons—white-black, white-Hispanic, and black- Hispanic—we find considerable convergence in homicide rates over the past two decades. Consistent with expectations, structural disadvantage is one of the strongest predictors of levels and changes in racial/ethnic violence disparities. In contrast to predictions based on strain theory, racial/ethnic wealth inequality has not increased disparities in homicide. Immigration, on the other hand, appears to be associated with declining white-black homicide differences. Consistent with an incapacitation/deterrence perspective, greater racial/ethnic incarceration disparities are associated with smaller racial/ethnic gaps in homicide. -

Race and the Criminal Justice System 1

RACE AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM 1 RACE AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM: A STUDY OF RACIAL BIAS AND RACIAL INJUSTICE By Nicole C. Haug Advised by Professor Chris Bickel SOC 461, 462 Senior Project Social Sciences Department College of Liberal Arts CALIFORNIA POLYTECHNIC STATE UNIVERSITY Fall, 2012 © 2012 Nicole Haug RACE AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM 2 Table of Contents Research Proposal…………………………………………………………………………………3 Annotated Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………..4 Outline…………………………………………………………………………………………….9 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………10 Research………………………………………………………………………………………….12 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….35 References………………………………………………………………………………………..37 RACE AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM 3 Research Proposal The goal of my senior project is to study how race influences criminal justice issues such as punitive crime policy, contact with law enforcement officers, profiling, and incarceration, etc. I intend to study the history of crime policy in the U.S. and whether or not racial bias within the criminal justice system exists (especially against African Americans) and if racial neutrality is even possible. I will conduct my research using library and academic sources, such as books and peer-reviewed scholarly journal articles, as well as web sources. I will specifically use sources that highlight the racial disparities found within the criminal justice system, and that offer critical and sociological explanations for those disparities. My hypothesis is that I will find that racial bias in the criminal justice system has created the racial disparities that exist and that racial neutrality within the system is unlikely. RACE AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM 4 Annotated Bibliography Alexander, M. (2010). The new jim crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness . New York: The New Press. -

ADULT CORRECTIONAL SERVICES in CANADA, 1998-99 by Jennifer Thomas

Statistics Canada – Catalogue no. 85-002-XIE Vol. 20 no. 3 ADULT CORRECTIONAL SERVICES IN CANADA, 1998-99 by Jennifer Thomas HIGHLIGHTS T At any given time, in 1998-99, there was an average of 150,986 adults under the supervision of correctional authorities in Canada, a 3% decrease from 1997-98. Almost 8 out of every 10 (79%) offenders in the correctional system were under some form of supervision in the community. Custodial facilities housed 21% of supervised offenders (including individuals on remand and held for other temporary reasons such as immigration holds). T For the sixth consecutive year, the total number of adult admissions to custody declined. In 1998-99, there were 218,009 adults admitted to provincial/territorial and federal custody, a 3% decrease over 1997-98. Since the peak of custodial admissions in 1992-93 (following almost a decade of growth), the number of custodial admissions has decreased by 14%. T The majority of adult custodial admissions (97%) were to provincial/territorial facilities. Although provincial/territorial admissions to custody continued to decline (3%) in 1998-99, admissions to federal facilities rose by 3%. T Similar to custodial admissions, admissions to sentenced community supervision (i.e., probation and conditional sentences) declined (2%) in 1998-99, the first time since the introduction of the conditional sentence in 1996. Admissions to conditional sentences totalled 14,236 for the year, a 3% decrease over 1997-98, while admissions to probation declined slightly (2%), totalling 78,819. T The typical adult offender admitted on sentence to a provincial/territorial facility was male, between the ages of 18 and 34, and convicted of a property offence. -

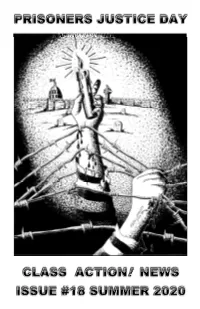

Class Action News Issue #18 Summer 2020

- 1 - 2 > CAN-#18 < Editor’s Note > < Contents > It is Summer & Issue #18 News …………………………... 3-12 of ‘Class Action News’. Health & Harm Reduction …..…... 13 This magazine is by & for Resources ………….……….... 14-16 the Prisoner Class in Canada. < Artists in this Issue > In every Issue we provide a safe space for creative expression and literacy development. Cover: Pete Collins These zines feature art, poetry, stories, news, observations, concerns, and anything of interest to share. Health & Harm Reduction info will always be provided - Yes, Be Safe! Quality & Quantity: Items printed are those that are common for diverse readers, so no religious items please. < Funding for this Issue > Artwork: Black pen (tat-style) works the best. Cover Artist will receive a $25 donation. Very special thanks to: Writings: only short poems, news, stories, … Groundswell Community Justice Trust Fund! Items selected are those that fit nicely & allow space for others (½ page = 325 words max). < Ancestral Territorial Acknowledgment > For author protection, letters & story credits will all be 'Anonymous'. We respectfully acknowledge that the land on which Prison Free Press operates is the ‘Class Action News' is published 4 times a Traditional Territory of the Wendat, the year & is free for prisoners in Canada. Anishnaabeg, Haudenosaunee, and the If you are on the outside or an organization, Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation. please send a donation. We do not have any funding so it really helps to get this inside! e ‘Dish With One Spoon’ Treaty f Editor: Tom Jackson Canadian Charter of Rights & Freedoms Publication: Class Action News Publisher: PrisonFreePress.org • The right of life, liberty and security of person PO Box 39, Stn P (Section 7). -

Was Stephen Harper Really Tough on Crime? a Systems and Symbolic Action Analysis

Was Stephen Harper Really Tough on Crime? A Systems and Symbolic Action Analysis A thesis submitted to The College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfilment of the requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Department of Sociology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Mark Jacob Stobbe ©Mark Jacob Stobbe, September 2018. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirement for a postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or part, for scholarly purposes, may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis was done. It is understood that any copying, publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Request for permission to copy or use of whole or part of this thesis may be addressed to: Department of Sociology University of Saskatchewan 1019 - 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, SK Canada S7N 5A5 OR College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies University of Saskatchewan Room 116 Thorvaldson Building, 110 Science Place Saskatoon SK Canada S7N 5C9 i ABSTRACT In 2006, the Hon. -

Theoretical Perspectives on Race and Crime

Theoretical CHAPTER 3 Perspectives on Race and Crime A wide variety of sociological, psychological, and biological theories have been proposed to explain the underlying causes of crime and its social, spatial, and temporal distribution. All of these theories are based on the assumptions that crime is accurately measured. But when variation in crime patterns and characteristics is partially attributable to unreliability in the measurement of crime, it is impossible to empirically validate the accuracy of competing criminological theories. —Mosher, Miethe, and Hart (2011, p. 205) onsidering the historical and contemporary crime and victimization data and sta- tistics presented in Chapter 2, the logical next question is, What explains the crime patterns of each race? Based on this question, we have formulated two goals for this C chapter. First, we want to provide readers with a rudimentary overview of theory. Second, we want to provide readers with a summary of the numerous theories that have relevance for explaining race and crime. In addition to this, where available, we also discuss the results of tests of the theories reviewed. Last, we also document some of the shortcom- ings of each theory. Decades ago, criminology textbooks devoted a chapter to race and crime (Gabbidon & Taylor Greene, 2001). Today most texts cover the topic, but only in a cursory way. In general, because of the additional focus on race and crime, scholars have written more specialized books, such as this one, to more comprehensively cover the subject. But even in these cases, many authors devote little time to reviewing specific theories related to race and crime (Walker, Spohn, & DeLone, 2012). -

The State of Aboriginal Corrections: Best

The views expressed in this report are those of the author and are not necessarily those of the Department of the Solicitor General of Canada. EXAMINING ABORIGINAL CORRECTIONS IN CANADA APC 14 CA (1996) ABORIGINAL PEOPLES COLLECTION Cover: Addventures/Ottawa Figure: Leo Yerxa © Supply and Services Canada Cat. No. JS5-1/14-1996E ISBN: 0-662-24856-2 EXAMINING ABORIGINAL CORRECTIONS IN CANADA by Carol LaPrairie, Ph.D. assisted by Phil Mun Bruno Steinke in consultation with Ed Buller Sharon McCue Aboriginal Corrections Ministry of the Solicitor General 1996 EXAMINING ABORIGINAL CORRECTIONS IN CANADA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This document provides information gathered though surveys, analyses of quantitative data and a review of current literature and research about the state of aboriginal corrections. Its purpose is to inform program and policy makers, aboriginal organizations and services, academics, and others interested in the field. It is also intended to be used in the development of research and program evaluation plans, and to provide new directions to be considered for aboriginal corrections, theoretical issues and responses to aboriginal offenders. It raises some complex questions about the meaning and future of aboriginal corrections. The report is in nine parts. While there is a natural progression from one part to the next, each can be read alone as the subject matter is discrete and specific. Because of the quantity of data in some parts, summaries are presented at the end of each. Relevant tables are provided at the end of parts. Listings of “lessons learned” and suggested future research directions are also provided. In addition, there is an extensive reference section on mainstream and aboriginal correctional literature. -

Volume 22, No. 1

Nikkei NIKKEI national museum & cultural centre IMAGES Nikkei national museum N2017:ikke 75th Anniversaryi of the Japanese Canadian Internment cultuChildrenral running cen along thet dirtre road at the Bay Farm internment site, about a mile south from Slocan City. Bay Farm, circa 1942. NNM 1996.178.1.9 A publication of the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre ISSN #1203-9017 Volume 22, No. 1 Welcome to Nikkei Images Contents Nikkei Images is a publication of the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Nikkei national museum Centre dedicated to the preservation & cultural centre and sharing of Japanese Canadian stories since 1996. We welcome proposals of family Nikkei Images is published by the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre and community stories for publication in future Editorial Committee: Sherri Kajiwara, Linda Kawamoto Reid, issues. Articles must be between 500 – 3,500 words Carolyn Nakagawa, Erica Isomura maximum and fi nished work should be accompanied Design: John Endo Greenaway by relevant high resolution photographs with proper Subscription to Nikkei Images is free (with pre-paid postage) photo credits. Please send a brief description or with your yearly membership to NNMCC: Family $47.25 | Individual $36.75 summary of the theme and topic of your proposed Senior Individual $26.25N | Non-profiikke t $52.25 i article to [email protected]. Our publishing $2 per copy (plus npostage)atio forn anon-membersl museum agreement can be found online at centre.nikkeiplace. NNMCC Our Journey: Revisiting Tashme and mensch. Karl Konishi – a Memoir 6688 Southoaks Crescent org/nikkei-images New Denver After 70 Years Page 8 Page 10 Burnaby, BC, V5E 4M7 Canada Page 4 TEL: 604.777.7000 FAX: 604.777.7001 www.nikkeiplace.org Disclaimer: Every e ort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained within Nikkei Images.