Towards a Poetics of Knowledge and Place-Making in Nineteenth Century Voyaging Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“It Was Chiefly by Our Intimacy with the Natives That We

‘“It was chiefly by our intimacy with the natives that we succeeded in getting so many new birds”: Travelling Knowledges, Indigenous/European Encounters, and Colonial Science: Case Studies from Australia and Aotearoa in the wake of Cook’ Dr Michael Davis Honorary Research Fellow, Department of Sociology and Social Policy The University of Sydney [email protected] Continuing a long line of imperial scientific collecting voyages in the wake of James Cook, in 1850 John MacGillivray, naturalist on the British survey ship HMS Rattlesnake, which travelled to northern Australia and Papua New Guinea during 1846-1850, wrote to the ornithologist John Gould, ‘It was chiefly by our intimacy with the natives that we succeeded in getting so many new birds’. Only a few years earlier, on his many botanical collecting expeditions into the interior of New Zealand’s North Island, William Colenso, like MacGillivray, also acknowledged the role of local Indigenous knowledge. In one journey in December 1842, Colenso observed that ‘in the houses of the natives at this place a quantity of a thick succulent species of Fucus hung up to dry which they informed me was used as an article of food’. Colenso had a reflective sensibility, engaging Cook’s 1769 voyage as a point of reference for his own botanising. He wrote in December 1841, while in Tokomaru Bay, that this was ‘a spot which by the Naturalist will ever be contemplated with the most pleasant association of feeling, for here it was that Sir Joseph Banks and Dr Solander first botanized in October 1769. This bay was called Tegadoo by Cook’/ In this paper I interrogate writings from these two mid-19th century natural history collectors – one coastal voyager, the other predominantly inland explorer - to contemplate the complex entanglements between local Indigenous, and intruding Western, scientific knowledge systems in the decades following Cook and Banks, and inquire into the ways these knowledges melded together in situated encounters in time and place, to result in new knowledge formations. -

Aboriginal Camps and “Villages” in Southeast Queensland Tim O’Rourke University of Queensland

Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand 30, Open Papers presented to the 30th Annual Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand held on the Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, July 2-5, 2013. http://www.griffith.edu.au/conference/sahanz-2013/ Tim O’Rourke, “Aboriginal Camps and ‘Villages’ in Southeast Queensland” in Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 30, Open, edited by Alexandra Brown and Andrew Leach (Gold Coast, Qld: SAHANZ, 2013), vol. 2, p 851-863. ISBN-10: 0-9876055-0-X ISBN-13: 978-0-9876055-0-4 Aboriginal Camps and “Villages” in Southeast Queensland Tim O’Rourke University of Queensland In the early nineteenth century, European accounts of Southeast Queensland occasionally refer to larger Aboriginal camps as “villages”. Predominantly in coastal locations, the reported clusters of well-thatched domical structures had the appearance of permanent settlements. Elsewhere in the early contact period, and across geographically diverse regions of the continent, Aboriginal camps with certain morphological and architectural characteristics were labelled “villages” by European explorers and settlers. In the Encyclopaedia of Australian Architecture, Paul Memmott’s entry on Aboriginal architecture includes a description of semi- permanent camps under the subheading “Village architecture.” This paper analyses the relatively sparse archival records of nineteenth century Aboriginal camps and settlement patterns along the coastal edge of Southeast Queensland. These data are compared with the settlement patterns of Aboriginal groups in northeastern Queensland, also characterized by semi-sedentary campsites, but where later and different contact histories yield a more comprehensive picture of the built environment. -

Atoll Research Bulletin No. 252 Bird and Denis Islands

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 252 BIRD AND DENIS ISLANDS, SEYCHELLES by D. R. Stoddart and F. R. Fosberg Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Washington, D. C., U.S.A. ~ul~'l981 Contents 1. Geography and ecology of Bird Island, Seychelles Introduction Morphology and structure Climate Vegetation Flora Invertebrates Reptiles Mammals Birds History 2. Plants recorded from Bird Island 3. Geography and ecology of Denis Island, Seychelles Introduction Morphology and structure Climate Vegetation Flora Invertebrates Reptiles Mammals Birds History 4. Plants recorded from Denis Island 5. References Manuscript received May 1980 --Eds. List of Figures 1. The Seychelles Bank following page 11 2. Bird Island in 1976 following page 11 3. Beach sediment at Bird Island following page 11 4. Denis Island in 1977 following page 50 5. Monthly rainfall at Denis Island, 19 71-1962 following page 50 List of Tables 1. Scientific studies at Bird Island 2. Characteristics of Bird Island beach sands 3. Monthly rainfall at Bird Island, 1951-1962 4. Key to the literature on insects collected at Bird Island 5. Scientific studies at Denis Island 6. Monthly and annual rainfall records at Denis Island iii List of Plates Bird Island: Suriana zone on the northeast shore following page 11 Bird Island: Pisonia and Cordia woodland with Suriana on the northeast shore Bird Island: Tournefortia parkland in the northeast Bird Island: tree-like Tournefortia in the northeast Bird Island: pioneer sedges and Scaevola on the east shore Bird Island: pioneer Ipomoea pes-caprae on the east shore Bird Island: pioneer sedges, Scaevola and Tournefortia on the northeast shore Bird Island: airstrip from the southeast Denis Island: phosphate cliffs with Casuarina woodland, southwest shore following page 50 10. -

Great Southern Land: the Maritime Exploration of Terra Australis

GREAT SOUTHERN The Maritime Exploration of Terra Australis LAND Michael Pearson the australian government department of the environment and heritage, 2005 On the cover photo: Port Campbell, Vic. map: detail, Chart of Tasman’s photograph by John Baker discoveries in Tasmania. Department of the Environment From ‘Original Chart of the and Heritage Discovery of Tasmania’ by Isaac Gilsemans, Plate 97, volume 4, The anchors are from the from ‘Monumenta cartographica: Reproductions of unique and wreck of the ‘Marie Gabrielle’, rare maps, plans and views in a French built three-masted the actual size of the originals: barque of 250 tons built in accompanied by cartographical Nantes in 1864. She was monographs edited by Frederick driven ashore during a Casper Wieder, published y gale, on Wreck Beach near Martinus Nijhoff, the Hague, Moonlight Head on the 1925-1933. Victorian Coast at 1.00 am on National Library of Australia the morning of 25 November 1869, while carrying a cargo of tea from Foochow in China to Melbourne. © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth, available from the Department of the Environment and Heritage. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Assistant Secretary Heritage Assessment Branch Department of the Environment and Heritage GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment and Heritage. -

Is Agrosaurus Macgillivrayi Australia's Oldest Dinosaur?

Records of the Western Australian Museum Supplement No. 57: 191-200 (1999). Is Agrosaurus macgillivrayi Australia's oldest dinosaur? 1 2 3 Patricia Vickers-Rich , Thomas H. Rich , Gregory C. McNamara and Angela MilnerA 1 Monash Science Centre, Earth Sciences Department, Monash University, Clayton, Vic 3168; email: [email protected] 2 Museum Victoria, PO Box 666E, Melbourne, Vic 3001 }Albert Kersten Geocentre, PO Box 448, Broken Hill, NSW 2880 4 Department of Palaeontology, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK Abstract - The holotype and only known specimen of the prosauropod Agrosaunls macgillivrayi Seeley, 1891 probably comes from the Late Triassic Durdham Down locality near Bristol, England. Originally it was reported as being from the northeast coast of Australia. Firsthand examination of the most plausible northeast Australian source for such a fossil, outcrops of the Jurassic Helby Beds exposed on the east coast of Cape York Peninsula, have demonstrated that the rock in that unit was quite unlike that associated with the holotype. Gross and trace element comparisons between possible fossil bone fragments from the Helby Beds and the holotype also showed them to be quite different. On the other hand, similar comparisons between the holotype and fossil bone from Durdham Down showed them to be quite comparable, as were the rocks and microvertebrates there and the ones associated with the holotype. Furthermore, A. macgillivrayi is probably a junior synonym of Tlzecodontosaurus antiquus Morris, 1843 from Durdham Down. INTRODUCTION (Figure 3). The only locality information available In 1844, four British ships headed by H.M.s. -

ROYAL BOTANIC GARDENS, KEW Records and Collections, 1768-1954 Reels M730-88

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT ROYAL BOTANIC GARDENS, KEW Records and collections, 1768-1954 Reels M730-88 Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Richmond London TW9 3AE National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1970-71 CONTENTS Page 4 Historical note 7 Kew collectors series, 1814-55 9 Papers relating to collectors, 1791-1865 10 Official correspondence of Sir William Hooker, 1825-65 17 Official correspondence, 1865-1928 30 Miscellaneous manuscripts 30 Manuscript of James Backhouse 30 Letters to John G. Baker, 1883-90 31 Papers of Sir Joseph Banks, 1768-1819 33 Papers of George Bentham, 1834-1882 35 Papers of Henry Burkill, 1893-1937 35 Records of HMS Challenger, 1874-76 36 Manuscript of Frederick Christian 36 Papers of Charles Baron Clarke 36 Papers of William Colenso, 1841-52 37 Manuscript of Harold Comber, 1929-30 37 Manuscripts of Allan Cunningham, 1826-35 38 Letter of Charles Darwin, 1835 38 Letters to John Duthie, 1878-1905 38 Manuscripts of A.D.E. Elmer, 1907-17 39 Fern lists, 1846-1904 41 Papers of Henry Forbes, 1881-86 41 Correspondence of William Forsyth, 1790 42 Notebook of Henry Guppy, 1885 42 Manuscript of Clara Hemsley, 1898 42 Letters to William Hemsley, 1881-1916 43 Correspondence of John Henslow, 1838-39 43 Diaries of Sir Arthur Hill, 1927-28 43 Papers of Sir Joseph Hooker, 1840-1914 2 48 Manuscript of Janet Hutton 49 Inwards and outwards books, 1793-1895 58 Letters of William Kerr, 1809 59 Correspondence of Aylmer Bourke Lambert, 1821-40 59 Notebooks of L.V. -

William Macgillivray

WILLIAM MACGILLIVRAY “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project William MacGillivray HDT WHAT? INDEX WILLIAM MACGILLIVRAY WILLIAM MACGILLIVRAY 1796 January 25, Monday: William MacGillivray was born in Aberdeen, Scotland, the product of William MacGillivray upon Ann Wishart out of wedlock. We are unable to track the father and one possibility is that while a “Cameron Highlanders” fighting in the Peninsular wars, he was one of the battle casualties. This child would be brought up on the isle of Harris off the north coast of Scotland by the family of the father and would then as an adult go to reside in Edinburgh. Bastardy would seem to have been consequential as, although Charles Darwin would in private notations make reference to MacGillivray as “accurate,” we also can now observe that there had been a side comment by the gentleman naturalist of Down — that this ornithologist with whom he had dealings was not in possession of “the manners or appearance of a gentleman.” NOBODY COULD GUESS WHAT WOULD HAPPEN NEXT William MacGillivray “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX WILLIAM MACGILLIVRAY WILLIAM MACGILLIVRAY 1815 William MacGillivray graduated from King’s College at Aberdeen. He would attempt but not complete the course in medicine, deciding that instead he would “devote his attention exclusively to natural history.” Back home on the island of Harris to the north of Scotland, he would for a period teach at his old school, while studying a dead walrus, and while stuffing a bear he had been asked to kill. -

SHORT NOTE the Visit by John Macgillivray to the Kermadec

Notornis, 2007, Vol. 54: 229-230 229 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. SHORT NOTE The visit by John MacGillivray to the Kermadec Islands in 1854 and the discovery and description of the Kermadec petrel (Pterodroma neglecta) W.R.P. BOURNE Ardgath, Station Road, Dufftown, by Keith, AB55 4AX, United Kingdom [email protected] A.C.F. DAVID Oak End, West Monkton, Taunton, Somerset TA2 8QZ, United Kingdom It has long seemed strange that the Kermadec asterisks which may imply that he took specimens, petrels (Pterodroma neglecta Schlegel, 1863) collected including the following species with presumed by a British warship were first described in the modern names in brackets: Athene (an owl Netherlands. Recent accounts of the voyage of feather); *Halcyon vagans (New Zealand kingfisher HMS Herald (David 1995), and of its naturalist Halcyon sacra); *Prosthemadera concinnata (tui P. John MacGillivray (Ralph 1993), have helped to novaeseelandiae); *Platycercus pacificus (Kermadec elucidate the chain of events leading to the apparent parakeet Cyanorhamphus novaezelandiae cyanurus); anomaly. *Sula personata (masked booby Sula dactylatra); John MacGillivray was the wayward son of Phaeton phoenicurus (red-tailed tropicbird P. one of the greatest British ornithologists, William rubricauda); *Sterna n. sp. (grey ternlet Procelsterna MacGillivray, friend of J.J. Audubon (Ralph 1999). cerulea); *Onychoprion fuliginosus (sooty tern Sterna He became a ship’s naturalist like Joseph Banks, fuscata); Diomedea exulans (albatross Diomedea sp.); Charles Darwin, Thomas Huxley, and Joseph Diomedea chlororhyncha (mollymawk Thalassarche Hooker, but unlike them went little further. While sp.); Procellaria gigantea (giant petrel Macronectes he was an excellent field observer and made good sp.); Procellaria hasitata (black-capped petrel notes, he was irresponsible in his private life Pterodroma (cervicalis?); *Procellaria n. -

Science at Sea the Rattlesnake: a Voyage of Discovery to the Coral Sea by Jordan Goodman

Update Endeavour Vol.29 No.4 December 2005 Book Review Science at sea The Rattlesnake: A Voyage of Discovery to the Coral Sea by Jordan Goodman. Faber and Faber, 2005. £18.99 (357 pages, hardback) ISBN 0571210732 Paul White Department of History and Philosophy of Science, Free School Lane, Cambridge, UK CB2 3RH The expedition of the HMS Rattlesnake continuously in a cramped position, watching the dial of is little known in the history of science, the patent log and noting all soundings at every half-tenth of save perhaps as the maiden voyage of a mile. Vivid sketches are drawn of colonial life at various Thomas Huxley, which launched the ports of call: Madeira, where Huxley and the Reverend young naturalist on a successful career Robert King were offended by the smell of ‘garlicky in comparative zoology. In The Rattle- humanity’ at Christmas mass; Mauritius, where the ship’s snake: AVoyage of Discovery to the Coral officers made a pilgrimage to the tombs offictional characters Sea Jordan Goodman does provide some from Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s popular novel Paul et account of the innovative research on Virginie; and Port Essington, a remote colonial outpost in marine invertebrates that Huxley con- Northern Australia, notable for its busy cemetery. Stan- ducted during the voyage, and cites at length from his ley’s unofficial activities convey a sense of the survey ship colourful diary and letters. But what The Rattlesnake really as a gentleman’s estate, outfitted with comfortable sofas provides is the other side of the picture painted by Huxley, for his sisters en route to Madeira for convalescence and a his biographers and historians of marine biology; namely a magic lantern for entertaining guests. -

Fire Mountains of the Islands a History of Volcanic Eruptions and Disaster Management in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands

Fire Mountains of the Islands A History of Volcanic Eruptions and Disaster Management in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands Fire Mountains of the Islands A History of Volcanic Eruptions and Disaster Management in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands R. Wally Johnson Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Johnson, R. W. (Robert Wallace) Title: Fire mountains of the islands [electronic resource] : a history of volcanic eruptions and disaster management in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands / R. Wally Johnson. ISBN: 9781922144225 (pbk.) 9781922144232 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Volcanic eruptions--Papua New Guinea. Volcanic eruptions--Solomon Islands. Emergency management--Papua New Guinea. Emergency management--Solomon Islands. Dewey Number: 363.3495095 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover image: John Siune. ‘Dispela helekopta kisim Praim Minista bilong PNG igo lukim volkenu pairap long Rabaul’. 1996. 85 x 60 cm. Acrylic on paper mounted on board. R.W. Johnson collection. Intellectual property rights are held by the artist. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Grin Press This edition © 2013 ANU E Press Contents Tables ix Illustrations xi Foreword xvii Acknowledgements and Sources xxi Volcano Names and Totals xxiii 1. -

Newsletter No

Newsletter No. 143 June 2010 Price: $5.00 Australian Systematic Botany Society Newsletter 143 (June 2010) AUSTRALIAN SYSTEMATIC BOTANY SOCIETY INCORPORATED Council President Vice President Peter Weston Dale Dixon National Herbarium of New South Wales Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney Mrs Macquaries Road Mrs Macquaries Road Sydney, NSW 2000 Sydney, NSW 2000 Tel: (02) 9231 8171 Tel: (02) 9231 8111 Fax: (02) 9241 2797 Fax: (02) 9251 7231 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Treasurer Secretary Michael Bayly Gillian Brown School of Botany School of Botany The University of Melbourne, Vic. 3010 The University of Melbourne, Vic. 3010 Tel: (03) 8344 7150 Tel: (03) 8344 7150 Fax: (03) 9347 5460 Fax: (03) 9347 5460 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Councillor Councillor Frank Zich Tanya Scharaschkin Australian Tropical Herbarium School of Natural Resource Sciences E2 building, J.C.U. Cairns Campus Queensland University of Technology PO Box 6811 PO Box 2434 Cairns, Qld 4870 Brisbane, Qld 4001 Tel: (07) 4059 5014 Tel: (07) 3138 1395 Fax: (07) 4091 8888 Fax: (07) 3138 1535 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Other Constitutional Bodies Public Officer Hansjörg Eichler Research Committee Annette Wilson Bill Barker Australian Bilogical Resources Study Betsy Jackes Dept of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts Greg Leach GPO Box 787 Kristina Lemson Canberra, ACT 2601 Chris Quinn Chair: Dale Dixon, Vice President Affiliate Society Grant applications close: 14 March 2010. Papua New Guinea Botanical Society ASBS Website www.anbg.gov.au/asbs Cover image: Alloxylon flammeum (Proteaceae), Webmaster: Murray Fagg reproduced with the permission of David Mackay (the Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research artist) and RBG Sydney. -

1847 – the Ball After Returning from the Picnic

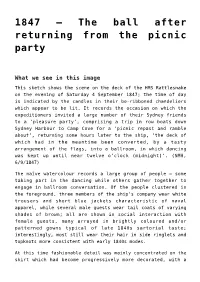

1847 – The ball after returning from the picnic party What we see in this image This sketch shows the scene on the deck of the HMS Rattlesnake on the evening of Saturday 4 September 1847; the time of day is indicated by the candles in their be-ribboned chandeliers which appear to be lit. It records the occasion on which the expeditioners invited a large number of their Sydney friends to a ‘pleasure party’, comprising a trip in row boats down Sydney Harbour to Camp Cove for a ‘picnic repast and ramble about’, returning some hours later to the ship, ‘the deck of which had in the meantime been converted, by a tasty arrangement of the flags, into a ballroom, in which dancing was kept up until near twelve o’clock (midnight)’. (SMH, 6/9/1847) The naïve watercolour records a large group of people – some taking part in the dancing while others gather together to engage in ballroom conversation. Of the people clustered in the foreground, three members of the ship’s company wear white trousers and short blue jackets characteristic of naval apparel, while several male guests wear tail coats of varying shades of brown; all are shown in social interaction with female guests, many arrayed in brightly coloured and/or patterned gowns typical of late 1840s sartorial taste; interestingly, most still wear their hair in side ringlets and topknots more consistent with early 1840s modes. At this time fashionable detail was mainly concentrated on the skirt which had become progressively more decorated, with a preference for double skirts and flounces especially with scalloped edges.