American Black Nightshade. Whereas S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sharon J. Collman WSU Snohomish County Extension Green Gardening Workshop October 21, 2015 Definition

Sharon J. Collman WSU Snohomish County Extension Green Gardening Workshop October 21, 2015 Definition AKA exotic, alien, non-native, introduced, non-indigenous, or foreign sp. National Invasive Species Council definition: (1) “a non-native (alien) to the ecosystem” (2) “a species likely to cause economic or harm to human health or environment” Not all invasive species are foreign origin (Spartina, bullfrog) Not all foreign species are invasive (Most US ag species are not native) Definition increasingly includes exotic diseases (West Nile virus, anthrax etc.) Can include genetically modified/ engineered and transgenic organisms Executive Order 13112 (1999) Directed Federal agencies to make IS a priority, and: “Identify any actions which could affect the status of invasive species; use their respective programs & authorities to prevent introductions; detect & respond rapidly to invasions; monitor populations restore native species & habitats in invaded ecosystems conduct research; and promote public education.” Not authorize, fund, or carry out actions that cause/promote IS intro/spread Political, Social, Habitat, Ecological, Environmental, Economic, Health, Trade & Commerce, & Climate Change Considerations Historical Perspective Native Americans – Early explorers – Plant explorers in Europe Pioneers moving across the US Food - Plants – Stored products – Crops – renegade seed Animals – Insects – ants, slugs Travelers – gardeners exchanging plants with friends Invasive Species… …can also be moved by • Household goods • Vehicles -

Weedsoc.Org.Au

THE WEED SOCIETY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Inc. Website: www.nswweedsoc.org.au Seminar Papers WEEDS – WOE to GO IV Wednesday 6 September 2006 Metcalfe Auditorium State Library of NSW Macquarie Street , SYDNEY Sponsors Collated / Edited by Copies of this publication are available from: Dr Stephen Johnson THE WEED SOCIETY & Bob Trounce OF NEW SOUTH WALES Inc. PO Box 438 WAHROONGA NSW 2076 THE WEED SOCIETY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Inc. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Seminar Organising Committee Lawrie Greenup (chair) Mike Barrett Bertie Hennecke Luc Streit Coordinator power point presentations Erica McKay Welcome to speakers and delegates Warwick Felton (President) Summary of the day’s presentations Mike Barrett Collation and preparation of proceedings Stephen Johnson Bob Trounce The committee thanks all who took part and attended the seminar and particularly the speakers for their presentations and supply of written documents for these proceedings. THE WEED SOCIETY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Inc. SEMINAR SERIES: WEEDS WOE TO GO IV “Poisonous and Allergenic Plants Where are they?” Date: Wednesday 6th September 2006 Location: The Metcalfe Auditorium The State Library of NSW Macquarie Street Sydney Time Topic Speaker 9.00 – 9.30 am REGISTRATION & MORNING TEA 9.30 – 9.40 am Welcome Warwick Felton 9.40 – 10.30 am Weeds that make you sick Rachel McFadyen 10.30 – 11.20 am Poisonous, prickly, parasitic, pushy? John Virtue Prioritising weeds for coordinated control programs” 11.20 – 1130 am break 11.30 – 11.50 am Parietaria or Asthma Weed Sue Stevens Education & incentive project -

Of Physalis Longifolia in the U.S

The Ethnobotany and Ethnopharmacology of Wild Tomatillos, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and Related Physalis Species: A Review1 ,2 3 2 2 KELLY KINDSCHER* ,QUINN LONG ,STEVE CORBETT ,KIRSTEN BOSNAK , 2 4 5 HILLARY LORING ,MARK COHEN , AND BARBARA N. TIMMERMANN 2Kansas Biological Survey, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 3Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO, USA 4Department of Surgery, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA 5Department of Medicinal Chemistry, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA *Corresponding author; e-mail: [email protected] The Ethnobotany and Ethnopharmacology of Wild Tomatillos, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and Related Physalis Species: A Review. The wild tomatillo, Physalis longifolia Nutt., and related species have been important wild-harvested foods and medicinal plants. This paper reviews their traditional use as food and medicine; it also discusses taxonomic difficulties and provides information on recent medicinal chemistry discoveries within this and related species. Subtle morphological differences recognized by taxonomists to distinguish this species from closely related taxa can be confusing to botanists and ethnobotanists, and many of these differences are not considered to be important by indigenous people. Therefore, the food and medicinal uses reported here include information for P. longifolia, as well as uses for several related taxa found north of Mexico. The importance of wild Physalis species as food is reported by many tribes, and its long history of use is evidenced by frequent discovery in archaeological sites. These plants may have been cultivated, or “tended,” by Pueblo farmers and other tribes. The importance of this plant as medicine is made evident through its historical ethnobotanical use, information in recent literature on Physalis species pharmacology, and our Native Medicinal Plant Research Program’s recent discovery of 14 new natural products, some of which have potent anti-cancer activity. -

Solanum Pseudocapsicum

Solanum pseudocapsicum COMMON NAME Jerusalem cherry FAMILY Solanaceae AUTHORITY Solanum pseudocapsicum L. FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Exotic STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE SOLPSE HABITAT Bartons Bush, Trentham. Apr 2006. Terrestrial. Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe FEATURES Erect, unarmed shrub, glabrous or sometimes with few branched hairs on very young shoots; stems wiry, 40~120cm tall. Petiole to 2cm long, slender. Lamina 3~12 x 1~3cm, lanceolate or elliptic-lanceolate, glossy above; margins usu. undulate; base narrowly attenuate; apex obtuse or acute. Flowers 1~several; peduncle 0~8mm long; pedicels 5~10mm long, erect at fruiting. Calyx 4~5mm long; lobes lanceolate to ovate, slightly accrescent. Corolla approx. 15mm diam., white, glabrous; lobes oblong- ovate to triangular. Anthers 2.5~3mm long. Berry 1.5~2cm diam., globose, glossy, orange to scarlet, long-persistent; stone cells 0. Seeds approx. Bartons Bush, Trentham. Apr 2006. 3mm diam., suborbicular to reniform or obovoid, rather asymmetric; Photographer: Jeremy Rolfe margin thickened. (-Webb et. al., 1988) SIMILAR TAXA A plant with attractive glossy orange or red berries around 1-2 cm diameter (Department of Conservation 1996). FLOWERING October, November, December, January, February, March, April, May FLOWER COLOURS White, Yellow YEAR NATURALISED 1935 ORIGIN Eastern Sth America ETYMOLOGY solanum: Derivation uncertain - possibly from the Latin word sol, meaning “sun,” referring to its status as a plant of the sun. Another possibility is that the root was solare, meaning “to soothe,” or solamen, meaning “a comfort,” which would refer to the soothing effects of the plant upon ingestion. Reason For Introduction Ornamental Life Cycle Comments Perennial. Dispersal Seed is bird dispersed (Webb et al., 1988; Department of Conservation 1996). -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

Natural and Synthetic Derivatives of the Steroidal Glycoalkaloids of Solanum Genus and Biological Activity

Natural Products Chemistry & Research Review Article Natural and Synthetic Derivatives of the Steroidal Glycoalkaloids of Solanum Genus and Biological Activity Morillo M1, Rojas J1, Lequart V2, Lamarti A 3 , Martin P2* 1Faculty of Pharmacy and Bioanalysis, Research Institute, University of Los Andes, Mérida P.C. 5101, Venezuela; 2University Artois, UniLasalle, Unité Transformations & Agroressources – ULR7519, F-62408 Béthune, France; 3Laboratory of Plant Biotechnology, Biology Department, Faculty of Sciences, Abdelmalek Essaadi University, Tetouan, Morocco ABSTRACT Steroidal alkaloids are secondary metabolites mainly isolated from species of Solanaceae and Liliaceae families that occurs mostly as glycoalkaloids. α-chaconine, α-solanine, solamargine and solasonine are among the steroidal glycoalkaloids commonly isolated from Solanum species. A number of investigations have demonstrated that steroidal glycoalkaloids exhibit a variety of biological and pharmacological activities such as antitumor, teratogenic, antifungal, antiviral, among others. However, these are toxic to many organisms and are generally considered to be defensive allelochemicals. To date, over 200 alkaloids have been isolated from many Solanum species, all of these possess the C27 cholestane skeleton and have been divided into five structural types; solanidine, spirosolanes, solacongestidine, solanocapsine, and jurbidine. In this regard, the steroidal C27 solasodine type alkaloids are considered as significant target of synthetic derivatives and have been investigated -

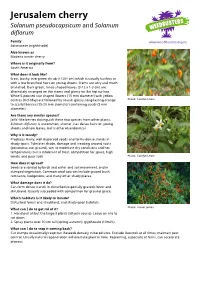

Jerusalem Cherry Solanum Pseudocapsicum and Solanum Diflorum

Jerusalem cherry Solanum pseudocapsicum and Solanum diflorum Family Solanaceae (nightshade) Also known as Madeira winter cherry Where is it originally from? South America What does it look like? Erect, bushy, evergreen shrub (<120+ cm) which is usually hairless or with a few branched hairs on young shoots. Stems are wiry and much branched. Dark green, lance-shaped leaves (3-12 x 1-3 cm) are alternately arranged on the stems and glossy on the top surface. White 5-pointed star shaped flowers (15 mm diameter) with yellow centres (Oct-May) are followed by round, glossy, long-lasting orange Photo: Carolyn Lewis to scarlet berries (15-20 mm diameter) containing seeds (3 mm diameter). Are there any similar species? Jaffa'-like berries distinguish these two species from other plants. Solanum diflorum is uncommon, shorter, has dense hairs on young shoots and new leaves, but is otherwise identical. Why is it weedy? Produces many, well dispersed seeds and forms dense stands in shady spots. Tolerates shade, damage and treading around roots (poisonous, not grazed), wet to moderate dry conditions and hot temperatures but is intolerant of frost, competition for space, high winds, and poor soils. Photo: Carolyn Lewis How does it spread? Seeds are spread by birds and water and soil movement, and in dumped vegetation. Common seed sources include grazed bush remnants, hedgerows, and many other shady places. What damage does it do? Can form dense stands in disturbed (especially grazed) forest and shrubland. Usually succeeded with competition for ground space. Which habitats is it likely to invade? Disturbed forest and shrubland, and shady open habitats. -

Vascular Plants and a Brief History of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands

United States Department of Agriculture Vascular Plants and a Brief Forest Service Rocky Mountain History of the Kiowa and Rita Research Station General Technical Report Blanca National Grasslands RMRS-GTR-233 December 2009 Donald L. Hazlett, Michael H. Schiebout, and Paulette L. Ford Hazlett, Donald L.; Schiebout, Michael H.; and Ford, Paulette L. 2009. Vascular plants and a brief history of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS- GTR-233. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 44 p. Abstract Administered by the USDA Forest Service, the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands occupy 230,000 acres of public land extending from northeastern New Mexico into the panhandles of Oklahoma and Texas. A mosaic of topographic features including canyons, plateaus, rolling grasslands and outcrops supports a diverse flora. Eight hundred twenty six (826) species of vascular plant species representing 81 plant families are known to occur on or near these public lands. This report includes a history of the area; ethnobotanical information; an introductory overview of the area including its climate, geology, vegetation, habitats, fauna, and ecological history; and a plant survey and information about the rare, poisonous, and exotic species from the area. A vascular plant checklist of 816 vascular plant taxa in the appendix includes scientific and common names, habitat types, and general distribution data for each species. This list is based on extensive plant collections and available herbarium collections. Authors Donald L. Hazlett is an ethnobotanist, Director of New World Plants and People consulting, and a research associate at the Denver Botanic Gardens, Denver, CO. -

Garden Plants Poisonous to People

N NO V E M B E R 2 0 0 6 P R I M E F A C T 3 5 9 ( R E P L A C E S A G F A C T P 7 . 1 . 1 P O I S O N O U S P L A N T S I N T H E G A R D E N) Garden plants poisonous to people Annie Johnson Table 1. Toxicity rating for Tables 2−7. Weeds Project Officer Rating Toxicity Stephen Johnson Mildly toxic. Mild symptoms may occur if large * Weed Ecologist quantities are eaten. Toxic. Causes discomfort and irritation but not Weeds Unit, Biosecurity Compliance and Mine ** Safety, Orange dangerous to life. Highly toxic. Capable of causing serious illness *** or death. Introduction There are a range of garden plants that are considered poisonous. Poisonings and deaths from garden plants Poisoning are rare as most poisonous plants taste unpleasant Poisoning from plants may occur from ingesting, and are seldom swallowed (see toxicity). However, it is inhalation or direct contact. best to know which plants are potentially toxic. Symptoms from ingestion include gastroenteritis, It is important to remember that small children are diarrhoea, vomiting, nervous symptoms and in serious often at risk from coloured berries, petals and leaves cases, respiratory and cardiac distress. Poisoning that look succulent. This does not mean that all these by inhalation of pollen, dust or fumes from burning poisonous plants should be avoided or removed from plants can cause symptoms similar to hay fever or the garden. It is best to teach children never to eat asthma. -

An Introduction to Pepino (Solanum Muricatum Aiton)

International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology (IJEAB) Vol-1, Issue-2, July -Aug- 2016] ISSN: 2456-1878 An introduction to Pepino ( Solanum muricatum Aiton): Review S. K. Mahato, S. Gurung, S. Chakravarty, B. Chhetri, T. Khawas Regional Research Station (Hill Zone), Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Kalimpong, Darjeeling, West Bengal, India Abstract — During the past few decades there has been America, Morocco, Spain, Israel and the highlands of renewed interest in pepino cultivation both in the Andean Kenya, as the pepino is considered a crop with potential for region and in several other countries, as the pepino is diversification of horticultural production (Munoz et al, considered a crop with potential for diversification of 2014). In the United States the fruit is known to have been horticultural production. grown in San Diego before 1889 and in Santa Barbara by It a species of evergreen shrub and vegetative propagated 1897 but now a days, several hundred hectares of the fruit by stem cuttings and esteemed for its edible fruit. Fruits are are grown on a small scale in Hawaii and California. The juicy, scented, mild sweet and colour may be white, cream, plant is grown primarily in Chile, New yellow, maroon, or purplish, sometimes with purple stripes Zealand and Western Australia. In Chile, more than 400 at maturity, whilst the shape may be spherical, conical, hectares are planted in the Longotoma Valley with an heart-shaped or horn-shaped. Apart from its attractive increasing proportion of the harvest being exported. morphological features, the pepino fruit has been attributed Recently, the pepino has been common in markets antioxidant, antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory and in Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru and Chile and grown antitumoral activities. -

Modern Techniques in Colorado Potato Beetle (Leptinotarsa Decemlineata Say) Control and Resistance Management: History Review and Future Perspectives

insects Review Modern Techniques in Colorado Potato Beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say) Control and Resistance Management: History Review and Future Perspectives Martina Kadoi´cBalaško 1,* , Katarina M. Mikac 2 , Renata Bažok 1 and Darija Lemic 1 1 Department of Agricultural Zoology, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Zagreb, Svetošimunska 25, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; [email protected] (R.B.); [email protected] (D.L.) 2 Centre for Sustainable Ecosystem Solutions, School of Earth, Atmospheric and Life Sciences, Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health, University of Wollongong, Wollongong 2522, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +385-1-239-3654 Received: 8 July 2020; Accepted: 22 August 2020; Published: 1 September 2020 Simple Summary: The Colorado potato beetle (CPB) is one of the most important potato pest worldwide. It is native to U.S. but during the 20th century it has dispersed through Europe, Asia and western China. It continues to expand in an east and southeast direction. Damages are caused by larvae and adults. Their feeding on potato plant leaves can cause complete defoliation and lead to a large yield loss. After the long period of using only chemical control measures, the emergence of resistance increased and some new and different methods come to the fore. The main focus of this review is on new approaches to the old CPB control problem. We describe the use of Bacillus thuringiensis and RNA interference (RNAi) as possible solutions for the future in CPB management. RNAi has proven successful in controlling many pests and shows great potential for CPB control. Better understanding of the mechanisms that affect efficiency will enable the development of this technology and boost potential of RNAi to become part of integrated plant protection in the future. -

Meloidogyne Incognita) Kimaru S.L1*, Kimenju, J.W.2, Kilalo D.C2 & Onyango C.M2

G.J.B.A.H.S., Vol.3 (4):1-6 (October-December, 2014) ISSN: 2319 – 5584 GROWTH AND YIELD RESPONSE OF SELECTED SPECIES OF AFRICAN LEAFY VEGETABLES INFESTED WITH ROOT KNOT NEMATODES (Meloidogyne incognita) Kimaru S.L1*, Kimenju, J.W.2, Kilalo D.C2 & Onyango C.M2. 1Ministry of Education, P.o box 281-10201, Murang’a, Kenya. 2Department of Plant Science and Crop Protection, University of Nairobi, Kenya. P.o box 30197, Nairobi *Corresponding Author Abstract African indigenous leafy vegetables (AILVs) are an important commodity in the diet of many African communities. Most of the vegetables are grown by low-income small holder farmers and thus, play a crucial role in food security and in improving the nutritional status of poor families. However, root knot nematodes are a major hindrance to production with yield losses of 80 to 100 percent being recorded on some of the vegetables depending on susceptibility and inocula levels in the soil. The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of root knot nematodes on the growth and yield of popular AILVs. A greenhouse experiment was conducted twice, where AILVs namely spider plant (Cleome gynandra), amaranthus (Amaranthus hybridus), African night shade (Solanum nigrum), cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), jute mallow (Corchorus olitorius) and sun hemp (Crotalaria juncea) were tested. The seeds for each vegetable were planted in six pots out of which three of the pots were infested with 2000 second stage juveniles of root knot nematodes and data on plant height, fresh and dry shoot weight, galling index, egg mass index and the second stage juvenile count was recorded and analyzed.