EN BANC Promulgated: DISSENTING OPINION LEONEN, J.: I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Karapatan Yearend Report (WEB).Pdf

2017 KARAPATAN YEAR-END REPORT ON THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION IN THE PHILIPPINES Duterte’s Choice: The Tyrant Emerged 2017 Karapatan Year-End Report on the Human Rights Situation in the Philippines Duterte’s Choice: The Tyrant Emerged Published in the Philippines in 2018 by KARAPATAN 2/F Erythrina Bldg., 1 Maaralin St., Central District, Diliman Quezon City 1100 Philippines Telefax: (+63 2) 435 41 46 [email protected] www.karapatan.org KARAPATAN is an alliance of human rights organizations and programmes, human rights desks and committees of people’s organisations, and individual advocates committed to the defense and promotion of people’s rights and civil liberties. It monitors and documents cases of human rights violations, assists and defends victims, and conducts education, training and campaigns. Cover art by Archie Oclos “Mahal Ko Ang Pilipinas,” 4 ft x 8 ft mural, latex on plywood, 2017 Lay-out by Ron Villegas Photos/Images: Manila Bulletin, ABS-CBN, Altermidya, Kadamay, Karapatan Southern Mindanao, Karapatan Cagayan Valley, Bulatlat, Kilab Multimedia, IFI, Katungod Sinirangang Bisayas, Leonilo Doloricon, Renan Ortiz, Dee Ayroso, AFP-Getty Images, Bicol Today, Ilocos Human Rights Alliance, Interaksyon, RMP-NMR, Daily Mail UK, Alcadev, Obet de Castro, Cordillera Human Rights Alliance, Fox News, Rappler, Karapatan Western Mindanao, Humabol Bohol, Brigada News Davao, IBON, Crispin B. Beltran Resource Center, Tindeg Ranao, Carl Anthony Olalo, Luigi Almuena The reproduction and distribution of information contained in this publication are allowed as long as the sources are cited, and KARAPATAN is acknowledged as the source. Please furnish Karapatan copies of the final work where the quotation or citation appears. -

Free the the Department of Justice Has Already Submitted Its Health Workers Is Another Day Recommendations Regarding the Case of the 43 Health Workers

Another day in prison for the and their families tormented. FREE THE The Department of Justice has already submitted its health workers is another day recommendations regarding the case of the 43 health workers. The President himself has admitted that the that justice is denied. search warrant was defective and the alleged evidence President Benigno Aquino III should act now against the Morong 43 are the “fruit of the poisonous for the release of the Morong 43. tree.” Various local and international organizations Nine months ago in February, the 43 health workers have called for the health workers’ release. including 26 women – two of whom have already given When Malacañang granted amnesty to rebel birth while in prison – were illegally arrested, searched, soldiers, many asked why the Morong 43 remained 43! detained, and tortured. Their rights are still being violated in prison. We call on the Aquino government to withdraw the charges against the Morong 43 and release them unconditionally! Most Rev. Antonio Ledesma, Archbishop, Metropolitan Archdiocese of CDO • Atty. Roan Libarios, IBP • UN Ad Litem Judge Romeo Capulong • Former SolGen Atty. Frank Chavez • Farnoosh Hashemian, MPH, Nat’l Lawyers Guild • Rev. Nestor Gerente, UMC, CA • Danny Bernabe, Echo Atty. Socorro Eemac Cabreros, IBP Davao City Pres. (2009) • Atty. Federico Gapuz, UPLM • Atty. Beverly Park UMC • J. Luis Buktaw, UMC LA, CA • Sr. Corazon Demetillo, RGS • Maria Elizabeth Embry, Antioch Most Rev. Oscar Cruz, Archbishop Emeritus, Archdiocese of Lingayen • Most Selim-Musni • Atty. Edre Olalia, NUPL • Atty. Joven Laura, Atty. Julius Matibag, NUPL • Atty. Ephraim CA • Haniel Garibay, Nat’l Assoc. -

A Popular Strongman Gains More Power by Joseph Purugganan September 2019

Blickwechsel Gesellscha Umwelt Menschenrechte Armut Politik Entwicklung Demokratie Gerechtigkeit In the Aftermath of the 2019 Philippine Elections: A Popular Strongman Gains More Power By Joseph Purugganan September 2019 The Philippines concluded a high-stakes midterm elections in May 2019, that many consider a critical turning point in our nation’s history. While the Presidency was not on the line, and Rodrigo Duterte himself was not on the ballot, the polls were seen as a referendum on his presidency. Duterte has drawn flak for his deadly ‘War on In midterm elections, voters have historically fa- Drugs’ that has taken the lives of over 5,000 vored candidates backed by a popular incumbent suspects according to official police accounts, and rejected those supported by unpopular ones. but the death toll could be as high as 27,000 ac- In the 2013 midterms for instance, the adminis- cording to the Philippine Commission on Human tration supported by former President Benigno Rights. The administration has also been criti- Aquino III, won 9 out of 12 Senate seats. Like cized for its handling of the maritime conflict Duterte, Aquino had a high satisfaction rating with China in the West Philippine Sea. heading into the midterms. In contrast, a very unpopular Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, with neg- Going into the polls however, Duterte, despite ative net satisfaction ratings, weighed down the all the criticisms at home and abroad, has main- administration ticket. In the Senate race in 2007, tained consistently high popularity and trust the Genuine Opposition coalition was able to se- ratings. The latest survey conducted five months cure eight out of 12 Senate seats, while Arroyo’s ahead of the elections showed the President Team Unity only got two seats and the other two having a 76 percent trust score and an 81 percent slots went to independent candidates. -

FINAL REPORT of the NATIONAL FACT-FINDING and SOLIDARITY MISSION in NEGROS ORIENTAL, PHILIPPINES April 4-8, 2019

FINAL REPORT OF THE NATIONAL FACT-FINDING AND SOLIDARITY MISSION IN NEGROS ORIENTAL, PHILIPPINES April 4-8, 2019 CONTEXT On March 30, 2019, between 2:00am to 5:30am, fourteen (14) persons were killed by State security forces during their operations in Canlaon City, Manjuyod, and Sta. Catalina towns in Negros Oriental province in the Philippines. At least fifteen (15) persons were also reportedly arrested in the said localities, according to relatives of the victims and peasant organizations in the province. In a report by Bombo Radyo Cebu, the PNP Region 7 said that it launched its Simultaneous Enhanced Managing Police Operations (SEMPO) or Oplan Sawron in Negros Oriental. Central Visayas Police Regional Office (PRO-7) Chief Debold Sinas said that the police served 37 search warrants to “various personalities due to illegal possession of firearms.” He also said that they were able to serve 31 search warrants; 14 were killed when these personalities resisted arrests, while 12 others were arrested.1 In another article, Sinas also reportedly said that those who were killed were members of the CPP-NPA and that the 14 refused to surrender and engaged the police in a shoot-out. “They really fought. Even in Oplan Sauron Part 1, there was a directive from the top leadership of the rebels to fight it out with the police. They were not ready to surrender because they were hardcore rebels,” Sinas said.2 On April 1, 2019, PNP Chief Oscar Albayalde and Presidential Spokesperon Salvador Panelo said that these are legitimate police operations.3 1 http://www.bomboradyo.com/14-killed-12-arrested-in-series-of-pnp-operation-in-negros-oriental/ 2 https://www.philstar.com/the-freeman/cebu-news/2019/03/31/1906104/negros-oriental-14-rebels-dead 3 http://cnnphilippines.com/news/2019/4/1/pnp-probe-negros-oriental-operation-not-massacre.html 1 The mass killings and illegal arrests of farmers in Negros Oriental are the latest of the attacks against human rights defenders and of the long list of human rights violations documented under the Duterte administration. -

Action Against Torture Action Against Torture

ActionAction against Torture A Practical Guide to the Istanbul Protocol forfor Lawyers in the Philippines NovemberNovember 20072007 This Manual was written by the REDRESS TRUST as Part of the Prevention through Documentation Project, an initiative of the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims (IRCT), the World Medical Association (WMA), the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey (HRFT), and Physicians for Human Rights USA (PHR USA) For further information on this manual, please contact REDRESS at: 87 Vauxhall Walk, London SE11 5HJ Tel: +44 (0)20 7793 1777 Fax: +44 (0)20 7793 1719 [email protected] (general correspondence) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This manual is the outcome of a collaborative effort spanning several years of cooperation and involving lawyers, human rights defenders, doctors and others in the Philippines and elsewhere. REDRESS is especially grateful to all those who have contributed to the drafting of the manual by providing information, comments and/or suggestions, in particular Ellecer E. Carlos, Balay Rehabilitation Center, Inc.; Neri Colmenares, Associate (Asian Law Centre), Faculty of Law, University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; Maria Socorro I. Diokno, Secretary General, FLAG (Free Legal Assistance Group); Rogel ‘Gil’ Navarro, Chairman, Peace Advocates for Truth, Healing and Justice (PATH); Atty. Soliman Santos; Antonio Villasor, Peace & Human Rights Coordinator, Asian Cultural Forum for Development (ACFOD), as well as David Gates and Varsha Goyal for their research assistance. The manual was written by Lutz Oette, and edited by Carla Ferstman. IINNDDEEXX PART 1: OVERVIEW OF THE ISTANBUL PROTOCOL .......................................... 6 A. INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................................6 B. THE IMPORTANCE OF LEGAL PROFESSIONALS IN THE DOCUMENTATION AND INVESTIGATION OF TORTURE...............................................................................................8 C. -

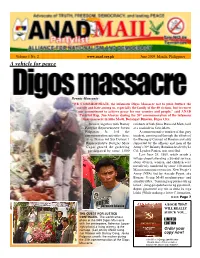

ANAD Mail June Issue.Pmd

Volume 1 No. 2 www.anad.org.ph June 2009 Manila, Philippines A vehicle for peace Dennis Monsanto “WE COMMEMORATE the infamous Digos Massacre not to push further the sorrow and hate among us, especially the family of the 40 victims, but to renew our commitment to achieve peace for our country and people,” said ANAD Partylist Rep. Jun Alcover during the 20th commemoration of the infamous Digos massacre in Sitio Matti, Barangay Binaton, Digos City. Alcover, together with Bantay residents of both Sitios Rano and Matti, held Partylist Representative Jovito at a roadside in Sitio Matti. Palparan Jr. led the A commemorative marker of that gory commemoration activities there. incident, constructed through the efforts of Also, Davao del Sur District 1 the Barangay Council of Binaton and ably Representative Douglas Marc supported by the officers and men of the Cagas graced the gathering Army’s 39th Infantry Battalion headed by Lt participated by some 1,000 Col. Lyndon Paniza, was unveiled. Last June 25, 1989, while inside a village chapel attending a Sunday service, about 40 men, women, and children were mercilessly murdered by some 120 armed Maoist communist terrorists New People’s Army (NPA) led by Amado Payot, aka Benzar. Using M-60 machineguns and armalite rifles. “Samtang nag porma sila ug letra C, ilang girapidohan mi ug gipamusil, dayon gipamutol ang ulo sa duha ka mga lalaki (While making a letter C formation, >>> Page 7 Adronico Edianon A BOOK THAT WILL REALLY THE QUEST FOR JUSTICE SHOCK YOU... CONTINUES. The world famous photo of the l989 Digos Massacre LIMITED with the centerpiece, Adronico (upper EDITION right photo) a living witness to the carnage. -

TWO YEARS of DUTERTE: Overture to a Rapid Political and Economic Decay

Art by Ugat Lahi. Photo ©Mel Matthew, Manila Today Manila ©Mel Matthew, Photo Art Lahi. Ugat by TWO YEARS OF DUTERTE: Overture to a rapid political and economic decay he “Duterte magic” is gradually getting dimmer. Collapsing with the weight of his own failures, Duterte is not only fumbling through the cracks now evident in his government, but is becoming more and more delusional following the successive backlash he is now receiving. TThis spiraling down has led the Duterte government to gravitate towards more repressive policies to tighten its grip on power. A hellish orchestra, manned by a vindictive concertmaster, has directed a cacophonous opus to play an ominous, grim score. Indeed, Duterte has allowed disgorged criminals such as former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and the wretched Marcos family to sneak back into power. His allies who have been relegated to political irrelevance are now out and about, singing their own tune but still careful to hum in chorus with Duterte. On July 23, 2018, the sneaky maneuvers paid off, and Gloria Arroyo was declared House Speaker of the House of Representatives. With elections coming up in 2019, the vultures have lined up, eager to receive Duterte’s blessings in anticipation that this will translate to public electoral support. Arrogating powers that only dictators have no shame doing, Duterte flexed his muscles when he jailed Senator Leila de Lima over alleged drug charges in 2016; when he allowed the burial of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos at the Libingan ng mga Bayani in the same year; when he declared martial law in Mindanao in 2017; when he ousted former Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno in 2018; and recently, when he scripted the arrest of critic Senator Antonio Trillanes III. -

Labindalawang Taon Ng Makakaliwang Grupong Party-List Sa Kongresong Pilipino

Labindalawang Taon ng Makakaliwang Grupong Party-list sa Kongresong Pilipino Preliminaryong Pag-aaral sa Panlehislatibong Rekord ng AKBAYAN at MAKABAYAN ATOY M. NAVARRO & ADONIS L. ELUMBRE Mahigit labindalawang taon matapos ipatupad ang Party-List System Act of 1995 sa eleksyon ng Mayo 1998, may pangangailangang patuloy na pag- aralan ang mga napanagumpayan ng mga makakaliwang grupong party- list sa Kongresong Pilipino. Bagamat may mga pag-aaral na hinggil sa aktibong pagkakaugnay sa mga kilusang panlipunan ng mga progresibong grupong party-list at pati na ang kanilang maaasahang papel bilang bantay- bayan sa Kamara ng mga Representante, wala pa talagang maituturing na pag-aaral sa panlehislatibong rekord ng mga makakaliwang grupong party- list na nagpopokus sa mga ipinasang batas. Tatangkaing punan ng preliminaryong pag-aaral na ito ang naturang kakulangan sa pamamagitan ng paghahain ng pangkalahatang pagtanaw sa mga Batas Republika na inakda bilang pangunahing may-akda o kasamang may-akda ng AKBAYAN at MAKABAYAN, dalawa sa pinakadeterminadong makakaliwang pagtatangkang palayain ang lehislaturang Pilipino sa tradisyunal na pulitika. Gayundin, titingnan ng pag-aaral na ito ang mga pagkakatugma at pagkakatunggali ng AKBAYAN at MAKABAYAN sa pagsusulong ng mga batas para sa repormang panlipunan. Magsisilbi ang pananaw sa mga pagkakatugma at pagkakatunggaling ito bilang tuntungan sa mga posibilidad para sa isang progresibong ajendang panlehislatibo sa ika-15 Kongresong Pilipino, kung saan naglilingkod ang AKBAYAN at MAKABAYAN bilang natitirang makakaliwang grupong party-list. Atoy M. Navarro, Forum for Ethical Review Committees in Asia and the Pacific (FERCAP), Thammasat University, Thailand, at Adonis L. Elumbre, Unibersidad ng Pilipinas Baguio. Email: [email protected]. Kinikilala ng mga may-akda ang ambag ng mga komentaryo nina Perci Cendana, Tin de Villa, at ng mga rebyuwer ng PSSR sa pagkakabuo ng artikulong ito. -

(UPOU). an Explorat

his paper is a self-reflection on the state of openness of the University of the Philippines Open University (UPOU). An exploratory and descriptive study, it aims not only to define the elements of openness of UPOU, but also to unravel the causes and solutions to the issues and concerns that limit its options to becoming a truly open university. It is based on four parameters of openness, which are widely universal in the literature, e.g., open admissions, open curricula, distance education at scale, and the co-creation, sharing and use of open educational resources (OER). It draws from the perception survey among peers, which the author conducted in UPOU in July and August 2012. It also relies on relevant secondary materials on the subject. What if you could revisit and download the questions you took during the UPCAT (University of the Philippines College Admission Test)? I received information that this will soon be a possibility. It’s not yet official though. For some people, including yours truly, this is the same set of questions that made and unmade dreams. Not all UPCAT takers make it. Only a small fraction pass the test. Some of the passers see it as a blessing. Some see it as fuel, firing their desire to keep working harder. Some see it as an entitlement — instant membership to an elite group. Whatever its worth, the UPCAT is the entryway to the University of the Philippines, a scholastic community with a unique and celebrated tradition spanning more than a century. But take heed — none of its legacy would have been possible if not for the hard work of Filipino taxpayers. -

ANG the Tiamzons' Arrest Is a Blow to the Peace Talks

Pahayagan ng Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas ANG Pinapatnubayan ng Marxismo-Leninismo-Maoismo English Edition Vol. XLV No. 7 April 7, 2014 www.philippinerevolution.net Editorial Declaration The Tiamzons' arrest of National is a blow Sovereignty and to the peace talks he arrest of Benito Tiam- trumped-up criminal charges and Patrimony zon and Wilma Austria, arresting the negotiators, con- Tboth leading cadres of the sultants and staff of either party Week Communist Party of the Philip- are strictly prohibited by the pines and peace talks consult- Joint Agreement on Safety and ants of the National Democratic Immunity Guarantees (JASIG). n the face of heighten- Front of the Philippines (NDFP) is Aquino and his officials por- ing US intervention, in- a gross violation of the peace tray the arrest of Comrades Be- Icreasing presence of US process. nito and Wilma as a step that and allied foreign troops, They were arrested with five moves the country closer to intensifying foreign eco- others in Aloguinsan, Cebu on peace, exposing anew their nar- nomic plunder and the wor- March 22. To justify their pro- row-minded view on peace. For sening puppetry of the longed detention, the arresting Aquino, peace will be achieved if Aquino regime to the US police and military operatives he could effect either the surren- government, the Commu- planted firearms and arrested der or arrest of the people's rev- nist Party of the Philippines them on a trumped-up case of olutionary forces struggling for (CPP) calls on the Filipino multiple murder. national liberation and democra- people and all their patri- The Aquino regime has once cy. -

Manifestation

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES SUPREME COURT MANILA EN BANC BAYAN MUNA PARTY-LIST REPRESENTATIVES CARLOS ISAGANI T. ZARATE, et al, Petitioners, GR NO. 252585 Consolidated with: 252578, 252579, 252580, 252613, 252623, 252624, and 252646 - versus - PRESIDENT RODRIGO DUTERTE, et al, Respondents. x---------------------------------------------------------------x MANIFESTATION Petitioners in GR No. 252585, by undersigned, to this Honorable Court, most respectfully aver: 1. On July 17, 2020 Petitioners in GR No. 252585 (Zarate Petition) received through electronic mail the Consolidated Comment filed by the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG). 2. In par. 176 of the Consolidated Comment, the OSG averred that the Zarate Petition has no attached Verification and Certification Against Forum Shopping. 3. Petitioner checked the copy they have filed with the Supreme Court on July 6, 2020, at 12:13PM, and the same definitely contains the Verification and Certification Against Forum Shopping of all the petitioners in the Zarate Petition. Attached herein is a copy of said receiving copy of the Petition with the Verification and Certification (sans annexes) for easy reference. A perusal of the Verification and Certification would show that the date of notarization is the same as the date of the filing of the Petition, or July 6, 2020. 4. If the furnished copy to the Respondents, including the OSG, is without any Verification and Certification Against Forum Shopping attached to the Petition, then such instance is due only to inadvertence, and not in any way intentionally done to violate the rules of procedure. 5. The Zarate Petition definitely complied with the Rules of Court pertaining to the submission of verification and certification against forum shopping, under Rule 7 Sections 4 and 5 of the Rules. -

Fact Finding and Solidarity Mission and People's Struggle Against Land Grabbing and Displacement in Coron and Busuanga, Palawa

Fact Finding and Solidarity Mission and the People’s Struggle Against Land Grabbing and Displacement in Coron and Busuanga, Palawan EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction The Katipunan ng Samahan ng Magbubukid sa Timog Katagalugan (KASAMA-TK) and Anakpawis - Southern Tagalog (Anakpawis-TK) jointly organized a National Fact Finding and Solidarity Mission (NFFSM) to the affected communities of the Yulo King Ranch (YKR) in Coron and Busuanga, Palawan from 14th to 20th of June 2014. The team is composed of representatives from Federation of Coron, Busuanga Farmers Association, KASAMA-TK, Anakpawis-TK, PAMALAKAYA-TK, Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (KMP), Anakpawis-National, Office of Bayan Muna Reps. Carlos Zarate and Neri Colmenares, Asian Peasant Coalition (APC), Ibon International, People’s Coalition on Food Sovereignty (PCFS), and Justice and Peace for the Integrity of God’s Creation - Baclaran, Permanent Commission on Social Mission Apostolate Redemptorists - Vice Province of Manila. The fact finding team aimed to consolidate narratives of residents from affected barangays (villages) to understand the history of the disputed land, know the plight and demands of the affected residents and formulate actions that will support and strengthen their rights to food, land and a dignified livelihood. They conducted interviews and focus group discussions in eight barangays namely, Decalachao, Guadalupe, San Jose, San Nicolas in Coron and in Quezon, New Busuanga, Cheey and Sto. Niño in Busuanga. Key Findings The Yulo King Ranch, which covers 39,238.93 hectares, is the largest agrarian anomaly in the country, where 22,268 hectares are in Coron and the remaining 16,970.53 hectares are in Busuanga. Of these, 12,817 has.