Is Butter Really Back?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutrient Comparison Chart

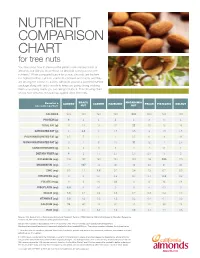

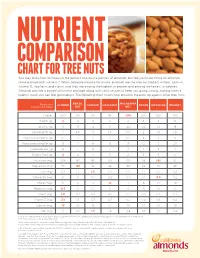

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART for tree nuts You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a satisfying snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT CALORIES 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 PROTEIN (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 TOTAL FAT (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 19 SATURATED FAT (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 POLYUNSATURATED FAT (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 MONOUNSATURATED FAT (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 CARBOHYDRATES (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 DIETARY FIBER (g) 4 2 1.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 3 2 POTASSIUM (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 MAGNESIUM (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 ZINC (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 VITAMIN B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 FOLATE (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 RIBOFLAVIN (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 NIACIN (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 VITAMIN E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.7 0.2 CALCIUM (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 IRON (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

Chart for Tree Nuts

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART FOR TREE NUTS You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the highest in protein and among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a healthy snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT Calories 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 Protein (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 Total Fat (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 18 Saturated Fat (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 Polyunsaturated Fat (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 Monounsaturated Fat (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 Carbohydrates (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 Dietary Fiber (g) 4 2 1 3 2 3 3 2 Potassium (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 Magnesium (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 Zinc (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 Vitamin B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 Folate (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 Riboflavin (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 Niacin (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 Vitamin E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.2 Calcium (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 Iron (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

Nutrition Handout N09: What Are the Types of Fat?

N09 What Are the Types of Fat? Most foods contain several different kinds of fat. Some are better for your health than others. It is wise to choose healthier types of fat, and enjoy them in moderation. Keep in mind that even healthier fats contain calories and should be used sparingly for weight management. Here is some information about healthy and harmful dietary fats. The four major types of fats are: • Monounsaturated fats • Polyunsaturated fats • Saturated fats • Trans fats Monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats are known as “healthy fats” because they are good for your heart, cholesterol levels, and overall health. These fats tend to be “liquid” at room temperature. Consider beneficial polyunsaturated fats containing Omega-3 fatty acids found in fatty fish, flaxseed, and walnuts. www.move.va.gov Nutrition Handouts • N09 Version 5.0 Page 1 of 3 Healthy Dietary Fats Monounsaturated Fat Polyunsaturated Fat Olive oil Soybean oil Canola oil Corn oil Sunflower oil Safflower oil Peanut oil Walnuts Olives Sunflower, sesame, and pumpkin seeds; flaxseed Nuts (almonds, peanuts, hazelnuts, Fatty fish (salmon, tuna, mackerel, herring, macadamia nuts, pecans, cashews) trout, anchovies, sardines, and eel) Avocados Soymilk Peanut butter Tofu Tips for increasing healthy fats in your diet: • Cook with olive oil. • Plan snacks of nuts or olives. • Eat more avocados. • Dress your own salads instead of using commercial dressings. Saturated fats and trans fats are known as the “harmful fats.” They increase your risk of disease and elevate cholesterol. Saturated fats tend to be solid at room temperature, but they are also found in liquid tropical oils (palm and coconut). -

Talking About Trans Fat: What You Need to Know

FOODFACTS From the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Talking About Trans Fat What You Need to Know Trans Fat at-a-Glance Fats in Your Diet Trans fat is a specific type of fat that is formed when liquid oils are turned Fat is a major source of energy for the body, into solid fats, such as shortening or stick margarine. During this process and aids in the absorption of vitamins A, — called hydrogenation — hydrogen is added to vegetable oil to increase D, E, and K, as well as carotenoids. Both the shelf life and flavor stability of foods. The result of the process is animal- and plant-derived food products trans fat. contain fat, and fat is important for proper growth, development, and maintenance of • fat can be found in many of the same foods as saturated fat, such Trans good health. as vegetable shortenings, some margarines, crackers, candies, cookies, snack foods, fried foods, baked goods, and other processed foods made However, experts recommend that you get with partially hydrogenated vegetable oils. about one third or less of your calories (i.e., between 20 and 35 percent of calories) • Also known as trans fatty acids, trans fat can be found naturally in some from fat. foods — such as animal-based foods like milk, milk products, and meat. • As a food ingredient, fat provides flavor, As a consumer, the most important thing to know about trans fat is that it consistency, and stability — and helps you behaves like saturated fat in the body by raising low-density lipoprotein feel full. -

Butter, Margarine, Vegetable Oils, and Olive Oil in the Average Polish Diet

nutrients Article Butter, Margarine, Vegetable Oils, and Olive Oil in the Average Polish Diet Hanna Górska-Warsewicz * , Krystyna Rejman , Wacław Laskowski and Maksymilian Czeczotko Department of Food Market and Consumer Research, Institute of Human Nutrition Sciences, Warsaw University of Life Sciences, 02-787 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] (K.R.); [email protected] (W.L.); [email protected] (M.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-22-5937144 Received: 13 November 2019; Accepted: 27 November 2019; Published: 3 December 2019 Abstract: The main aim of this study was to identify the sources of energy and 25 nutrients in fats and oils in the average Polish diet. We analyzed energy, total fat, saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), cholesterol, protein, carbohydrates, nine minerals, and nine vitamins. We included five sub-groups: butter, vegetable oils, margarine and other hydrogenated vegetable fats, olive oil, and other animal fats. The basis for our analysis was data from the 2016 household budget survey, conducted on a representative sample of the Polish population (36,886 households, n = 99,230). We used the cluster analysis to assess the impact of socio-demographic and economic factors on the volume of fats and oil consumption and on the share of particular products in the supply of energy and nutrients. Our findings indicated that fats and oils contributed 32.9% of the total fat supply, which placed these products in first position among main food groups. Meat and its products ranked second (30.8%) in the total fat supply, while milk and dairy products, including cream (13.4%), were the third food group. -

Saturated, Unsaturated, and Trans Fat

Lifestyle Coach Facilitation Guide: Post-Core Fats - Saturated, Unsaturated, and Trans Fat Content Overview This session answers the question “what is fat?” It explores the different types of fat, and shows which fats are healthy (monounsaturated and polyunsaturated) and which fats are unhealthy (saturated and trans fat). Participants learn tips for choosing foods with healthy fats and avoiding foods with unhealthy fats. More information on cholesterol appears in Post-Core Session: Heart Health. Lifestyle Coach Preparation Checklist Materials Post-core handouts: What is Fat? Healthy Fats: Omega-3, Monounsaturated and Polyunsaturated Fats to Avoid: Saturated and Trans Fat Identifying Healthier Alternatives Tips for Choosing the Best Types of Fat “Food and Activity Trackers” “Lifestyle Coach’s Log” Balance scale Post-Core: Fats – Saturated, Unsaturated, and Trans Fat Key messages to reinforce A completely fat-free diet would not be healthy, yet it is important that fat be consumed in moderation. The main types of “healthy” fats are monounsaturated and polyunsaturated. The main types of “unhealthy” fats are saturated and trans fat. Saturated fats are primarily found in foods that come from animals, such as meat and dairy. Try to switch to lower-fat versions of these foods. In order to avoid trans fat, look on nutrition labels for ingredients such as “partially hydrogenated” oils or shortening. In addition, look for trans fat in the nutritional information in products like commercially baked cookies, crackers, and pies, and fried foods. After the session At the completion of this session, do the following: Use the “Notes and Homework Page” for notes and follow-up tasks. -

Evaluation of Trans Fatty Acids Contents in Commercial Brands of Ghee Available at Indian Markets

Scientific Research and Essays Vol. 5(20), pp. 3193-3200, 18 October, 2010 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/SRE ISSN 1992-2248 ©2010 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Evaluation of trans fatty acids contents in commercial brands of ghee available at Indian markets Deepti Mahapatra1, Debashree Sethi1 and R. Balaji Raja2* 1Department of Biotechnology, SRM University, Kattankulathur, Tamilnadu, India. 2Department of Biotechnology, National Institute of Technology, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India. Accepted 15 September, 2010 Ghee has a considerable amount of trans fatty acids found in the form of alkanes, alkenes and alkynes. Trans fatty acids are quite harmful to general health of an individual especially the CVS (Cardio Vascular System). Accumulation of trans fatty acids in blood vessels and other tissues/organs of the body can have fatal effect especially in obese population. Four commercial brands of ghee found in Indian markets were chosen and their trans fatty acid content was determined by FTIR (Fourier Trans Infra Red) spectroscopy. The trans fatty acids were found in all the four brands with GRB having the highest concentration of it. Sakthi brand was observed to have moderate content of trans fatty acids. Aachi and RKG brands were having the least concentration of trans fatty acids. These results obtained from the present study would be aiding to an increase in consumer awareness about presence of trans fatty acids in food items and better appraisal by the companies and thus improving the current scenario. Key words: Ghee, trans fatty acids, FTIR, consumer awareness, cardiovascular system, public health, Indian market, food items. INTRODUCTION Ghee, also known as clarified butter in anglophone contains a significant amount of moisture, which must be countries, is made by simmering unsalted butter in a boiled off to create a clarified butter (Gaba and Jain, cooking vessel until all water has boiled off and the milk 1972). -

The Scoop on Coconut Oil Coconut Oil Is an Edible Oil Extracted from the “Meat” of Matured Coconuts

Family and Consumer Science/Extension Homemakers Club May/June 2016 The Scoop on Coconut Oil Coconut oil is an edible oil extracted from the “meat” of matured coconuts. It has several appli- cations in the food industry. It is used in processed foods because it is relatively inexpensive and can provide crisp texture to foods. Coconut oil has a high smoke point, the temperature where it starts to break down, which makes it shelf stable and ideal for foods that need a longer shelf-life. Hydrogenated and partially hydrogenated coconut oil are found in cereals, baked goods, biscuits, salty snacks, soaps, cosmetics and moisturizers. According to some health food promoters and celebrity doctors, coconut oil is the latest miracle food, claiming it can cure everything from heart disease to obesity and cancer. However, the ef- fects of coconut oil on health have not been well studied. These health claims tend to be based more on personal testimonials than on scientific evidence. In fact, there are very few studies in people showing benefits of coconut oil – most of these studies are epidemiology studies (e.g., population studies) that show a link between high coconut-consuming countries and longevity [1 -2]. Coconut oil is considered a saturated fat and contains 9 calories per gram. There are two basic types of fats – saturated and unsaturated. Unsaturated fats are healthy fats and include plant- based fats (such as vegetable oils and fats found in nuts, avocados and seeds) and fish oils. These fats should be the primary fats in your diet because they either do not affect cholesterol levels or they raise HDL (good) cholesterol without raising LDL (bad) cholesterol. -

Margarine.-Spreads.Pdf

MARGARINE & SPREADS The global margarine market has developed to include low- fat and low-salt spreads and products with added omega-3 fatty acids, plant sterols and certified oils, with a growing appeal to vegans searching for an alternative to butter OFI The global margarine/spread market is expected to grow with a single digit increase in CAGR between 2018 and 2028, according to a recent report by Persistence Market Research (PMR). Growth will be driven by consumer demand for food products high in nutritional value and low in fat and calorie content, and higher consumption in under-developed countries where margarine offers greater value for money Butter’s rival and multiple usages. Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès in 1869, who product called krona, made by churning a “The global market for margarine/spread responded to a challenge by Emperor blend of dairy cream and vegetable oils, is dominated by North America, which Napoleon III to create a butter substitute was introduced in Europe and, in 1982, a holds a significant market share, followed for the armed forces and lower classes. blend of cream and vegetable oils called by Europe and Asia-Pacific,” PMR says. The recipe was a mix of skimmed milk, Clover was introduced in the UK by the “North America is the largest consumer, water and animal fat. Milk Marketing Board. The vegetable oil especially due to the high consumption In 1871, Mège-Mouriès sold his patent and cream spread ‘I Can’t Believe It’s Not in food processing. Europe is the second to Dutch firm Jurgens. Jurgens realised Butter!’ was introduced into the USA in largest consumer. -

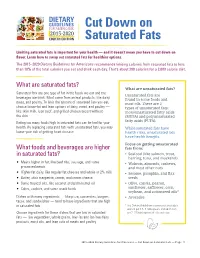

Cut Down on Saturated Fats

DIETARY GUIDELINES Cut Down on FOR AMERICANS 2015-2020 EIGHTH EDITION Saturated Fats Limiting saturated fats is important for your health — and it doesn’t mean you have to cut down on flavor. Learn how to swap out saturated fats for healthier options. The 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends limiting calories from saturated fats to less than 10% of the total calories you eat and drink each day. That’s about 200 calories for a 2,000 calorie diet. What are saturated fats? What are unsaturated fats? Saturated fats are one type of fat in the foods we eat and the Unsaturated fats are beverages we drink. Most come from animal products, like dairy, found in some foods and meat, and poultry. To limit the amount of saturated fats you eat, most oils. There are 2 choose lower-fat and lean options of dairy, meat, and poultry — types of unsaturated fats: like skim milk, lean beef, and grilled chicken breast without monounsaturated fatty acids the skin. (MUFA) and polyunsaturated Eating too many foods high in saturated fats can be bad for your fatty acids (PUFA). health. By replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats, you may While saturated fats have lower your risk of getting heart disease. health risks, unsaturated fats have health benefits. Focus on getting unsaturated What foods and beverages are higher fats from: in saturated fats? • Seafood (like salmon, trout, herring, tuna, and mackerel) • Meats higher in fat, like beef ribs, sausage, and some • W alnuts, almonds, cashews, processed meats and most other nuts • Higher-fat dairy, like regular-fat cheeses and whole or 2% milk • Sesame, pumpkin, and flax • Butter, stick margarine, cream, and cream cheese seeds • Some tropical oils, like coconut and palm kernel oil • Olive, canola, peanut, • Cakes, cookies, and some snack foods sunflower, safflower, corn, soybean, and cottonseed oils* Dishes with many ingredients — like pizza, casseroles, burgers, • A vocados tacos, and sandwiches — tend to have ingredients that are high in saturated fats. -

Coconut Oil: a Heart-Healthy Fat?1 Wendy M

FSHN17-1 Coconut Oil: A Heart-Healthy Fat?1 Wendy M. Gans and Gail P. A. Kauwell2 You have probably seen or heard claims on social media or Coconut even talk shows with health professionals about the health Coconut is a tropical fruit produced by coconut palm trees. benefits of coconut oil. Claims such as “Coconut oil de- Coconut has many uses. For example, it is frequently used creases cholesterol!” or “Coconut oil treats hypertension!” for its edible flesh and cool, refreshing coconut water. In are enough to interest any consumer looking for a quick fact, a popular way to quench your thirst in areas where cure for these health problems. Plus, coconut oil is sold coconuts are plentiful is to simply cut off the top and insert everywhere—from your local grocery store to the corner a straw. The coconut water can also be used to make coco drug store. But what is the evidence behind these health frio, a popular adult beverage. The fresh and dried forms claims? Does coconut oil have any health benefits? Read of the coconut flesh or “coconut meat” can be eaten as is on to learn more about coconut oil and how it might affect or cooked. Coconut meat is especially popular in many heart health. Southeast Asian dishes. In addition, the fat present in coconut meat can be extracted to produce coconut oil. Coconut oil can be used in cooking and in the production of shampoos, soaps, lotions, cosmetics, and fragrances. Coconut Oil The majority of coconut oil production occurs in Indonesia, the Philippines, and India. -

The Truth About Coconut Oil ( by Kathleen M

The Truth About Coconut Oil (http://www.webmd.com/diet/features/coconut-oil-and-health) By Kathleen M. Zelman, MPH, RD, LD, WebMD Expert Column Coconut oil, according to recent reports, is the latest food cure-all. Claims abound that coconut oil is a health food that can cure everything from poor immune function, thyroid disease, and heart disease, to obesity, cancer, and HIV. So should you stock up on coconut oil? Not so fast. The evidence that coconut oil is super-healthful is not convincing and these claims appear to be more testimonials than clinical evidence. There is very limited evidence on disease outcomes, says Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, DrPH, of Harvard Medical School and Harvard School of Public Health. "All that has been studied well is the impact of coconut oil on cholesterol levels and the findings are intriguing but we still don't know if it is harmful or beneficial," Mozaffarian says. Neither the American Heart Association (AHA) nor the U.S. government's 2010 Dietary Guidelines suggest that coconut oil is any better or preferable over other saturated fats. Coconut oil, like all saturated fats, should be limited to 7%-10% of calories because it can increase risk for heart disease, according to the AHA and 2010 Dietary Guidelines. What Is Coconut Oil? Pure virgin coconut oil, containing no hydrogenation (the process of adding hydrogen to make a liquid fat hard), contains 92% saturated fat -- the highest amount of saturated fat of any fat. Most saturated fats are solid at room temperature, found in animal products (such as meat, dairy, poultry with skin, and beef fat) and contain cholesterol.