The Invasion of Echo Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madonna: Kabbalah with the Kids! the Cast of the Bold Type Are Super Talented, So It’S Not Really Surprising to Madonna Makes a Quick Entrance Into Know That

JJ Jr. RSS Twitter Facebook Instagram MAIN ABOUT US EXCLUSIVE CONTACT SEND TIPS Search Chris Pine & Annabelle Wallis Miranda Lambert Mentions Will Smith & Jada Pinkett Smith You Won't Believe What One Hold Hands, Look So Cute Blake Shelton's Girlfriend Don't Say They're Married Woman Did to Protest Donald Together in London! Gwen Stefani in New Interview Anymore Find Out Why Trump (Hint: It's Terrifying) Older Newer SUN, 10 MARCH 2013 AT 7:30 PM Tweet 'The Bold Type' Cast Really Wants To Do A Musical Episode Madonna: Kabbalah with the Kids! The cast of The Bold Type are super talented, so it’s not really surprising to Madonna makes a quick entrance into know that... the Kabbalah Center while all bundled up for the chilly day on Saturday (March 9) in New York City. 'Free Rein' Returns To Netflix For The 54yearold entertainer was Season 2 on July 6th! Free Rein is almost here again and JJJ is accompanied by three of her children, so excited! The new season will center Lourdes, 16, Mercy, 8, and David, 7. on Zoe Phillips as... Last week, Madonna and Lourdes met up with some dancers from her MDNA tour at Antica Pesa in the Williamsburg Justin Bieber & GF Hailey Baldwin section of Brooklyn, where they dined on Head Out to Brooklyn... Justin Bieber and GF Hailey Baldwin are yummy Italian cuisine. continuing to have so much fun together! The 24yearold... An onlooker commented that Madonna seemed like the “coolest mom in the world,” according to People. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

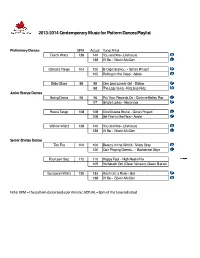

2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist

2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist Preliminary Dances BPM Act ual Tune/ Ar t ist Dut ch Walt z 138 140 You and Me - Lifehouse 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Can ast a Tan go 104 100 El Capitalismo... - Gotan Project 105 Rolling in the Deep - Adele Baby Bl ues 88 88 One Less Lonely Girl - Bieber 88 The Lazy Song - Kidz bop Kidz Ju n i o r Br o n z e D a n ce s Sw i n g Da n c e 96 96 Put Your Records On - Corinne Bailey Rae 97 Single Ladies - Beyoncee Fi est a Tango 108 108 Una Musica Brutal - Gotan Project 108 Set Fire to the Rain - Adele Willow Waltz 138 140 You and Me - Lifehouse 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Se ni or Br onze Da nce s Ten Fox 100 100 Beauty in the World - Macy Gray 100 Quit Playing Games... - Backstreet Boys Fo ur t een St ep 112 110 Happy Feet - High Heels Mix 109 Hollaback Girl (Clean Version)-Gwen Stefani Eu r o p ean Wal t z 135 133 Kiss from a Rose - Seal 138 I'll Be - Edwin McCain Note: BPM = the pattern dance beats per minute; ACTUAL = bpm of the tune indicated _____________________________________________________________________________________ 2013-2014 Contemporary Music for Pattern Dances Playlist pg2 Junior Silver Dances BPM Act ual Tune/ Ar t ist Keat s Foxt r ot 100 100 Beauty in the World - Macy Gray 100 Quit Playing Games... - Backstreet Boys Ro ck er Fo xt r o t 104 104 Black Horse & the Cherry Tree - KT Tunstall 104 Never See Your Face Again- Maroon 5 Harris Tango 108 108 Set Fire to the Rain - Adele 111 Gotan Project - Queremos Paz American Walt z 198 193 Fal l i n - Al i ci a Keys -

Gwen Stefani

luam keflezgy artistic director/choreographer selected credits contact: 818 509-0121 < MUSIC VIDEOS > Alicia Keys “Girl on Fire” Dir. Sophie Muller Beyonce “Run the World” Dir. Lawrence Francis Kelly Rowland “Motivation” Dir. Sarah Chatfield Beyonce “Move Your Body” (Asst. Choreographer) Chor. Frank Gatson Dawn Richards “Broken Record” Dir. Sarah McFClogan T Pain, Sophia Fresh “This Instant” Touch & Go J Status ft. Rihanna & Shontelle “Roll” Dir. Vashtie KolaCosmo Joe Buddens, Busta Rhymes, Li’l Mo “Fire” Dir. Paul Hunter Head Automatica “Beating Heart Baby” Dir. Jon Watts TV on the Radio “The Golden Age” Nappy Boy < COMMERCIALS > CK One “Trouble” Macy’s Back to School “The Summer Set” Charter Communication Nair Dir. Jimmy, Humble TV Converse Dir. Andrew Loevenguth Above the Influence Dir. Joaquim Baca-Asay Shoe Carnival Dir. Alex Weil MTV Hip Hop Week (10 Spots) Dir. Antonio MacDonald MTV MC Battle (5 Spots) Dir. Antonio MacDonald Mastercard Promo Campaign Dir. David Coolbirth MTV Direct Effect, Show Intro/ TV Spots Dir. Chike Ozah < TOURS / LIVE SHOWS > Alicia Keys -Set the World on Fire Tour RCA Records Alicia Keys - Europe Promo Tour RCA Records Britney Spears - Femme Fatale Tour Jive Records BET Awards -Kelly Rowland & Trey Songz BET BET Black Girls Rock Awards- Estelle BET Kelly Rowland 2010 Promo Art Director: Frank Gatson Kelly Rowland 2011 International Tour Art Director: Frank Gatson Black Girls Rock Awards- Jill Scott BET Neon Hitch Promo Tour Warner Bros BET Black Girls Rock Awards- Shontelle BET Day 26US Promo Tour Bad Boy BET BGR Awards- VV Brown BET Rihanna (Japan, US Promo Tour 2006) Def Jam Gwen Stefani Tour, opening act Rihanna Def Jam MTV Tempo Concert, Rihanna/Elephant Man Def Jam J Status US Tour (w/ Rihahna) SRP Records Kanye West & John Legend- Webster Hall GOOD Music Shontelle & Rihanna- House of Blues Tour Def Jam, SRP Shontelle & Rihanna- Bajan Music Awards Def Jam, SRP Shontelle & J Status- Rihanna House of Blues Tour < INDUSTRIALS > Athleta 2014 Fashion Week Latin Olympics Cola Cola Moncler, 2010 NY Fashion Week Dir. -

Gwen Stefani Is Still Showing Us How It’S Done—Woman, Wife, Mother, Designer—All 100 Percent Tabloid-Free

THE ALL-STAR FIFTEEN YEARS AFTER FIRST TOPPING THE CHARTS, NO DOUBT HAS A NEW ALBUM COMING, AND GWEN STEFANI IS STILL SHOWING US HOW IT’S DONE—WOMAN, WIFE, MOTHER, DESIGNER—ALL 100 PERCENT TABLOID-FREE. A ROCK ICON ON AND OFF STAGE, STEFANI TALKS MUSIC AND FASHION AND MAKING THE SLEEVE TO WEAR YOUR HEART ON. BY CANDICE RAINEY PHOTOGRAPHED BY dusan reljin S T Y L E D B Y andrea lieberman E L L E 284 www.elle.com EL0511_WLGwen_MND.indd 284 3/24/11 12:33 PM Beauty Secret: For a vintage-inspired cat- eye, pair liquid liner with doll-like lashes. Try Lineur Intense Liquid Eyeliner and Voluminous Mascara, both in black, by L’Oréal Paris. Left: Knitted jet-stone- beaded top over white-pearl- embroidered tank top and black fringe skirt, Gaultier Paris. Right: Sleeveless silk jumpsuit, Alessandra Rich, $2,200, visit net-a-porter.com. Necklace, Mawi, $645. For details, see Shopping Guide. www.elle.com 285 E L L E EL0511_WLGwen_MND.indd 285 3/24/11 12:33 PM E L L E 286 www.elle.com EL0511_WLGwen_MND.indd 286 3/24/11 12:33 PM Above left and right: Stretch crepe cape dress, L.A.M.B., $425, call 917-463-3553. Brass- plated pendant necklace with cubic zirconia, Noir Jewelry, $230. Leather pumps, Christian Louboutin, $595. Lower left and right: Stretch wool dress with leather trim, Givenchy by Riccardo Tisci, $4,010, at Hirshleifer’s, Manhasset, NY. Leather pumps, Christian Louboutin, $595. For details, see Shopping Guide. HAIR BY DANILO AT THE WALL GROUP; MAKEUP BY CHARLOTTE WILLER AT ART DEPARTMENT; MANICURE BY ELLE AT THE WALL GROUP; PROPS STYLED BY STOCKTON HALL AT 1+1 MGMT; FASHION ASSISTANT: JOAN REIDY www.elle.com 287 E L L E EL0511_WLGwen_MND.indd 287 3/24/11 12:33 PM Chrissie Hynde once said, “If you’re an ugly duckling—and most of us are, in rock bands—you’re not trying to look good. -

The Sweet Escape

The Sweet Escape Gwen Stefani Whohoe, whihoo Whohoe, whihoo Whohoe, whihoo Whohoe, whihoo If I could escape I would, but first of all let me say I must apologize for acting, stinking, treating you this way Cause I've been acting like sour milk fell on the floor It's your fault you didn't shut the refrigerator Maybe that's the reason I've been acting so cold If I could escape And re-create a place as my own world And I could be your favorite girl Forever, perfectly together Tell me boy, now wouldn't that be sweet? If I could be sweet I know I've been a real bad girl I didn't mean for you to get hurt Forever, we can make it better Tell me boy, now wouldn't that be sweet? Whohoe, whihoo Whohoe, whihoo Whohoe, whihoo Whohoe, whihoo You let me down I'm at my lowest boiling point Come help me out Questa pagina può essere fotocopiata esclusivamente per uso didattico - © Loescher Editore www.loescher.it/inenglish [email protected] 1 I need to get me out of this joint Come on, let's bounce Counting on you to turn me around Instead of clowning around let's look for some common ground So baby, times getting a little crazy I've been getting a little lazy Waiting for you to come save me I can see that you're angry By the way you treat me Hopefully you don't leave me Want to take you with me If I could escape And re-create a place as my own world And I could be your favorite girl Forever, perfectly together Tell me boy, now wouldn't that be sweet? If I could be sweet I know I've been a real bad girl I didn't mean for you to get hurt Forever, we -

Playnetwork Business Mixes

PlayNetwork Business Mixes 50s to Early 60s Marketing Strategy: Period themes, burgers and brews and pizza, bars, happy hour Era: Classic Compatible Music Styles: Fun-Time Oldies, Classic Description: All tempos and styles that had hits Rock, 70s Mix during the heyday of the 50s and into the early 60s, including some country as well Representative Artists: Elvis, Fats Domino, Steve 70s Mix Lawrence, Brenda Lee, Dinah Washington, Frankie Era: 70s Valli and the Four Seasons, Chubby Checker, The Impressions Description: An 8-track flashback of great music Appeal: People who can remember and appreciate from the 70s designed to inspire memories for the major musical moments from this era everyone. Featuring hits and historically significant album cuts from the “Far Out!,” Bob Newhart, Sanford Feel: All tempos and Son era Marketing Strategy: Hamburger/soda fountain– Representative Artists: The Eagles, Elton John, themed cafes, period-themed establishments, bars, Stevie Wonder, Jackson Brown, Gerry Rafferty, pizza establishments and clothing stores Chicago, Doobie Brothers, Brothers Johnson, Alan Parsons Project, Jim Croce, Joni Mitchell, Sugarloaf, Compatible Music Styles: Jukebox classics, Donut Steely Dan, Earth Wind & Fire, Paul Simon, Crosby, House Jukebox, Fun-Time Oldies, Innocent 40s, 50s, Stills, and Nash, Creedence Clearwater Revival, 60s Average White Band, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Electric Light Orchestra, Fleetwood Mac, Guess Who, 60s to Early 70s Billy Joel, Jefferson Starship, Steve Miller Band, Carly Simon, KC & the Sunshine Band, Van Morrison Era: Classic Feel: A warm blanket of familiar music that helped Description: Good-time pop and rock legends from define the analog sound of the 70s—including the the mid-60s through the early-to-mid-70s that marked one-hit wonders and the best known singer- the end of an era. -

Just a Girl Taking Over Las Vegas Interview by Allison Kugel

Just A Girl Taking Over Las Vegas Interview by Allison Kugel (laughs). But years later we are doing these residencies. “Being on stage in Las Vegas... She is a crazy worker, I look at her and I’m like... Wow! I forget how much it’s a part of I went backstage to talk to her after a show, she comes out of the dressing room looking like a Barbie Doll. She who I am. I’ve done it my whole was breathtaking on stage, but when you see her up life, pretty much. I think I don’t close, it’s like... It’s not possible you are so gorgeous! Allison: Did you choose Planet Hollywood? want to do it again, then I get Gwen: I feel like they chose me. What’s cool is Planet Hollywood is the Zappos Theatre; the team is incredible. on stage, even when I’m sound They take over with their creativity; it has a futuristic feel. checking, I’m like, “Oh My God, They give $1 of every ticket sold to the children’s charity, Cure 4 The Kids Foundation. You get motivated making I love this!” I love my music, a diference. To get on stage, share my story, and make I love being up there, I love money to give to children is amazing. I feel proud of that. Allison: Did Blake ofer you any creative input? the attention and I love being Gwen: He’s my best friend, so I bounce stuf of him able to share that love with all the time. -

Tia Rivera EPK

Choreographer Creative Director TIA RIVERA Entertainer and New York City native, Tia Rivera began dancing professionally at 17 and since then, Tia has performed globally with some of the world's biggest superstars. Her performance credits include working alongside Jennifer Lopez, Rihanna, Beyonce, Usher, Mariah Carey, Gwen Stefani, Kanye West, Ne-yo and many more. With the knowledge and experience she gained as a performer, Tia began working as a choreographer and movement coach to the stars. Some of Tia’s notable choreography credits include creating for Major Lazer, John Legend, Fergie, Gwen Stefani, and Halsey to name a few. Tia’s Choreography has been featured on the hit TV show Dance Moms season 7 as her mini’s took 1st place competing under Tia’s choreography and direction. Tia has also served as a choreographer for VH1 2016 Hip Hop Honors: All Hail The Queens, which took place at the Lincoln Center. Some of Tia’s notable spots include Toyota, Swarovski, GAP, and Crown Royal. As well as pursuing her career in entertainment, Tia also has a strong drive to provide motivation and education for aspiring entertainers. She teaches performance workshops and seminars, offering vital information and effective tools to succeed in todays industry. Through her love for public speaking and mentorship, Tia is helping shape the lives of many in pursuit of their own dreams. Puerto Rican, New York City native, the journey for happiness and success. Tia leads a vibrant and passionate life. From her established career as a dancer to her groundbreaking choreography, Tia was simply born to make an imprint on the world. -

Bouquet Toss

Most Requested Songs Back These lists are dynamically compiled based on online requests made over the past year at thousands of events around the world, where #1 is the most requested song. Select a List: Bouquet Toss List Results Artist Song Add to List 1 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 2 Meghan Trainor Dear Future Husband 3 Shania Twain Man! I Feel Like A Woman! 4 Cyndi Lauper Girls Just Want To Have Fun 5 David Guetta Feat. Flo Rida & Nicki... Where Them Girls At 6 Beyonce Run The World (Girls) 7 Spice Girls Wannabe 8 Ludacris Feat. Mystikal Move B***H 9 Christina Aguilera, Lil' Kim, Mya &... Lady Marmalade 10 Kelis Milkshake 11 Lizzo Good As Hell 12 Shania Twain Any Man Of Mine 13 Weather Girls It's Raining Men 14 Beyonce Love On Top 15 TLC No Scrubs 16 Kool & The Gang Ladies Night 17 Lizzo Truth Hurts 18 Pat Benatar Hit Me With Your Best Shot 19 Beyonce Formation 20 Beyonce Feat. Jay-Z Crazy In Love 21 Destiny's Child Jumpin, Jumpin 22 Blondie One Way Or Another 23 Destiny's Child Independent Women Part 1 24 Gwen Stefani Hollaback Girl 25 Keri Hilson Pretty Girl Rock 26 Queen Another One Bites The Dust 27 Roy Orbison Oh, Pretty Woman 28 ABBA Dancing Queen 29 Bruno Mars Marry You 30 Fifth Harmony That's My Girl 31 Fifth Harmony Feat. Kid Ink Worth It 32 Ginuwine Pony 33 Lizzo Juice 34 Martina Mcbride This One's For The Girls 35 Michael Jackson P.Y.T. -

Top Bouquet Toss Songs (Pdf) Download

Top Bouquet Toss Songs beyonce – single ladies (put a ring on it) meghan trainor – dear future husband cyndi lauper – girls just want to have fun shania twain – man! i feel like a woman! david guetta feat. flo rida & nicki minaj – where them girls at spice girls – wannabe beyonce run the world (girls) ludacris feat. mystikal – move b**** weather girls – it’s raining men pat benatar – hit me with your best shot kelis – milkshake tlc – no scrubs beyonce – formation kool & the gang – ladies night blondie – one way or another motley crue – girls, girls, girls christina aguilera, lil’ kim, mya & pink – lady marmalade beyonce – love on top little big town – little white church roy orbison – oh, pretty woman queen – another one bites the dust luke bryan – country girl (shake it for me) michael jackson – p.y.t. (pretty young thing) shania twain – any man of mine pat benatar – love is a battlefield carly rae jepsen – call me maybe miranda lambert duet with carrie underwood – somethin’ bad bruno mars – marry you survivor – eye of the tiger beastie boys – girls def leppard – pour some sugar on me diana ross & the supremes – you can’t hurry love michael buble – haven’t met you yet destiny’s child – independent women part 1 whitney houston – i wanna dance with somebody (who loves me) lenny kravitz – american woman martina mcbride – this one’s for the girls gwen stefani – hollaback girl beyonce feat. jay-z – crazy in love daft punk feat. pharrell williams – get lucky ginuwine – pony brooke valentine feat. big boi & lil’ jon – girlfight kanye west feat. jamie foxx – gold digger destiny’s child – bootylicious fifth harmony feat. -

500+ Awesome Wedding Song Ideas

500+ Awesome Song Ideas For Multi Genre Weddings No Song Name Artist Name 1 Sex On Fire Kings of Leon 2 Pump It (Radio) The Black Eyed Peas 3 Bye Bye Bye 'N Sync List Compiled By DJ Vibe 4 Empire State of Mind (Club) Jay Z ft Alicia Keys 5 Umbrella feat. Jay-Z (Clean) Rihanna - www.bookdjvibe.com 6 Rude Boy Rihanna - [email protected] 7 Move B***H (Clean) Ludacris ft. Mystikal & Infamous 2.0 8 In Da Club Dirty Intro 50 Cent - Wedding Page 9 She Aint You (Remix) Chris Brown ft SWV 10 California Love [Original Version] 2Pac ft Dr. Dre & Roger Troutman - 519 502 3558 11 Right Thurr (Clean) Chingy 12 Drop it like its hot Feat Pharell (Club) Snoop Dogg 13 Tipsy (Club) J-Kwon 14 Shy Guy Diana King 15 Southern Hopspitality (Clean) Ludacris 16 Return Of The Mack Mark Morrison 17 Fiesta R. Kelly 18 It Wasn't Me Shaggy 19 Who's That Girl (Clean) Eve 20 Summerlove (Remix) Justin Timberlake 21 Honey Mariah Carey 22 Party In The U.S.A. (96 Bpm) Miley Cyrus 23 Give It Up To Me [Instrumental] Sean Paul 24 Give It Up To Me Sean Paul (Feat. Keyshia Cole) 25 Disco Inferno (Clean) 50 Cent 26 Get Me Bodied [Extended Mix] Beyoncé 27 Single Ladies (Put a ring on it) Intro Beyonce 28 Calle Ocho Pit Bull 29 Rich Girl (Album Version) Gwen Stefani 30 Picture (Kid Rock featuring Sheryl Crow) Sheryl Crow 31 Crazy In Love (Feat. Jayz) Beyonce 32 I Just Wanna Love U (Give It 2 Me) (Clean) Jay-Z 33 Sexual Healing Max-A-Million 34 Pon De Replay Rihanna 35 Bailamos Enrique Iglesias 36 Uh Oooh (Remix - ft.