A Preliminary Report on Open Seat House Nominations in 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti-‐Science Climate Denier Caucus Georgia

ANTI-SCIENCE CLIMATE DENIER CAUCUS Climate change is happening, and humans are the cause. But a shocking number of congressional Republicans—more than 55 percent—refuse to accept it. One hundred and fifty-seven elected representatives from the 113th Congress have taken more than $51 million from the fossil-fuel industry, which is the driving force behind the carbon emissions that cause climate change. These representatives deny what more than 97 percent of climate scientists say is happening: Current human activity creates the greenhouse gas emissions that trap heat within the atmosphere and cause climate change. And their constituents are paying the price, with Americans across the nation suffering 368 climate-related national disaster declarations since 2011. There were 25 extreme weather events that each caused at least $1 billion in damage since 2011, including Superstorm Sandy and overwhelming drought that has covered almost the entire western half of the United States. Combined, these extreme weather events were responsible for 1,107 fatalities and up to $188 billion in economic damages. GEORGIA Despite the overwhelming scientific consensus and high costs to taxpayers, Georgia has seven resident deniers who have taken $783,233 in dirty energy contributions. The state has suffered five climate-related disaster declarations since 2011. Georgia suffered from “weather whiplash” this past May: excessive flooding where “exceptional drought,” the worst category of drought, had existed just a few months earlier. Below are quotes from five of Georgia’s resident deniers who refuse to believe there is a problem to address: Rep. Paul Broun (R-GA-10): “Scientists all over this world say that the idea of human induced global climate change is one of the greatest hoaxes perpetrated out of the scientific community. -

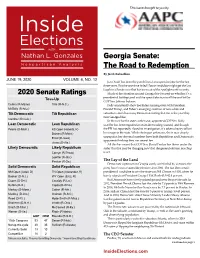

June 19, 2020 Volume 4, No

This issue brought to you by Georgia Senate: The Road to Redemption By Jacob Rubashkin JUNE 19, 2020 VOLUME 4, NO. 12 Jon Ossoff has been the punchline of an expensive joke for the last three years. But the one-time failed House candidate might get the last laugh in a Senate race that has been out of the spotlight until recently. 2020 Senate Ratings Much of the attention around Georgia has focused on whether it’s a Toss-Up presidential battleground and the special election to fill the seat left by GOP Sen. Johnny Isakson. Collins (R-Maine) Tillis (R-N.C.) Polls consistently show Joe Biden running even with President McSally (R-Ariz.) Donald Trump, and Biden’s emerging coalition of non-white and Tilt Democratic Tilt Republican suburban voters has many Democrats feeling that this is the year they turn Georgia blue. Gardner (R-Colo.) In the race for the state’s other seat, appointed-GOP Sen. Kelly Lean Democratic Lean Republican Loeffler has been engulfed in an insider trading scandal, and though Peters (D-Mich.) KS Open (Roberts, R) the FBI has reportedly closed its investigation, it’s taken a heavy toll on Daines (R-Mont.) her image in the state. While she began unknown, she is now deeply Ernst (R-Iowa) unpopular; her abysmal numbers have both Republican and Democratic opponents thinking they can unseat her. Jones (D-Ala.) All this has meant that GOP Sen. David Perdue has flown under the Likely Democratic Likely Republican radar. But that may be changing now that the general election matchup Cornyn (R-Texas) is set. -

Justice Reinvestment in Massachusetts Overview

Justice Reinvestment in Massachusetts Overview JANUARY 2016 Background uring the summer of 2015, Massachusetts state leaders STEERING COMMITTEE Drequested support from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Charlie Baker, Governor, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) and The Pew Charitable Robert DeLeo, House Speaker, Massachusetts House of Representatives Trusts (Pew) to use a “justice reinvestment” approach to develop Ralph Gants, Chief Justice, Supreme Judicial Court Karyn Polito, Lieutenant Governor, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts a data-driven policy framework to reduce corrections spending Stan Rosenberg, Senate President, Massachusetts Senate and reinvest savings in strategies that can reduce recidivism and improve public safety. As public-private partners in the Justice WORKING GROUP Reinvestment Initiative (JRI), BJA and Pew approved the state’s Co-Chairs request and asked The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice William Brownsberger, State Senator, Second Suffolk and Center to provide intensive technical assistance to help collect and Middlesex District Paula Carey, Chief Justice, Massachusetts Trial Court analyze data and develop appropriate policy options for the state. John Fernandes, State Representative, Tenth Worcester District Lon Povich, Chief Legal Counsel, Office of the Governor State leaders established the CSG Justice Center-Massachusetts Criminal Justice Review, a project led by a bipartisan, interbranch Members James G. Hicks, Chief, Natick Police steering committee and working group to support the justice Anthony Benedetti, Chief Counsel, Committee for Public reinvestment approach. The five-member steering committee is Counsel Services composed of Governor Charlie Baker, Lieutenant Governor Karyn Daniel Bennett, Secretary, Executive Office of Public Safety and Polito, Chief Justice Ralph Gants, Senate President Stan Rosenberg, Security (EOPSS) and House Speaker Robert DeLeo. -

Commissioners Meet with Georgia Congressional Delegation to Express Views on Pending Energy Legislation

Georgia Public Service 244 Washington St S.W. Contact: Bill Edge Atlanta, Georgia 30334 Phone 404-656-2316 Commission Phone: 404-656-4501 www.psc.state.ga.us Toll free: 800-282-5813 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 15-09 NEWS RELEASE Commissioners Meet with Georgia Congressional Delegation to Express Views on Pending Energy Legislation Atlanta, July 23, 2009 – Public Service Commission Chairman Doug Everett along with Commissioners Lauren “Bubba” McDonald, Jr. and Stan Wise traveled to the nation’s Capitol Wednesday to voice their concerns to Georgia’s Congressional Delegation about the pending energy and climate legislation, known as “cap and trade,” which will dramatically increase Georgian’s utility bills in the coming years. “Unless this legislation is modified and revised, Georgians could see their electric utility bills go up by as much as $66 a month by 2020,” said Everett. “Ultimately, we want to find a way to sculpt a bill that has less impact on Georgians,” Commissioner Stan Wise told the delegation members. Commission Vice-Chairman Lauren “Bubba” McDonald, Jr. said, “We were pleased with the reception afforded us by members of Georgia’s Congressional Delegation and will continue working with them through the legislative process.” Among the several key areas of concern brought to the Delegation’s attention: Allocations: Restricting, limiting and auctioning of allocations will increase rates to ratepayers. Delaying the phase out of allocations and beginning the auctions at a later date will give technologies time to develop to meet these requirements, mitigating impacts to customers. Dates and Caps: Requirements in the bill do not match with the timing for development of new technologies. -

You Didn't Build That Teepee!

Trump Talks Parenting & Politics The Guns of August at 100 Do Botched Executions Matter? UKIP Triumphs! JEFFREY LORD PETER HITCHENS JESSE WALKER vs. WILLIAM TUCKER JAMES DELINGPOLE JULY/AUGUST 2014 A MONTHLY REVIEW EDITED BY R. EMMETT TYRRELL, JR. You Didn’t Build That Teepee! Elizabeth Warren arouses the worst progressive fantasies. By Ira Stoll PLUS: Summer Books and Cocktails James Taranto, Jonathan Tobin, Freddy Gray, Helen Rittelmeyer, Eve Tushnet, Daniel Foster, Katherine Mangu-Ward…and more! Ukraine: A River Runs Through It Matthew Omolesky Schlesinger’s Excellent Bow Tie R.J. Stove Why I Quit Batman Tim Cavanaugh 1 5 1 5 1 5 1 5 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 100 100 100 100 “ The best detector is not merely the one that can pick up radar from the farthest distance, although the Valentine One continues to score best.” — Autoweek Now V1 comes to a touchscreen near you. Introducing the Threat Picture You can see the arrows at work on your compatible iPhone® or AndroidTM device. Check it out… The app is free! Yo u can download V1connection, the app Where’s the radar? It’s in the Box. for free. Go to the app store on your device. When installed, the app automatically runs in Demo Mode. No need to link to V1. Analyze preloaded threat situations on three different screens: on the V1 screen, Arrow in the Box means a threat in the radar zone. on Picture, and on List. Then when you’re ready to put the Threat Picture on duty in your car, order the Bluetooth® communication module directly from us. -

The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network

PLATFORMS AND OUTSIDERS IN PARTY NETWORKS: THE EVOLUTION OF THE DIGITAL POLITICAL ADVERTISING NETWORK Bridget Barrett A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Daniel Kreiss Adam Saffer Adam Sheingate © 2020 Bridget Barrett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Bridget Barrett: Platforms and Outsiders in Party Networks: The Evolution of the Digital Political Advertising Network (Under the direction of Daniel Kreiss) Scholars seldom examine the companies that campaigns hire to run digital advertising. This thesis presents the first network analysis of relationships between federal political committees (n = 2,077) and the companies they hired for electoral digital political advertising services (n = 1,034) across 13 years (2003–2016) and three election cycles (2008, 2012, and 2016). The network expanded from 333 nodes in 2008 to 2,202 nodes in 2016. In 2012 and 2016, Facebook and Google had the highest normalized betweenness centrality (.34 and .27 in 2012 and .55 and .24 in 2016 respectively). Given their positions in the network, Facebook and Google should be considered consequential members of party networks. Of advertising agencies hired in the 2016 electoral cycle, 23% had no declared political specialization and were hired disproportionately by non-incumbents. The thesis argues their motivations may not be as well-aligned with party goals as those of established political professionals. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES .................................................................................................................... V POLITICAL CONSULTING AND PARTY NETWORKS ............................................................................... -

ABSTRACT TAYLOR, JAMI KATHLEEN. the Adoption of Gender Identity Inclusive Legislation in the American States. (Under the Direct

ABSTRACT TAYLOR, JAMI KATHLEEN. The Adoption of Gender Identity Inclusive Legislation in the American States. (Under the direction of Andrew J. Taylor.) This research addresses an issue little studied in the public administration and political science literature, public policy affecting the transgender community. Policy domains addressed in the first chapter include vital records laws, health care, marriage, education, hate crimes and employment discrimination. As of 2007, twelve states statutorily protect transgender people from employment discrimination while ten include transgender persons under hate crimes laws. An exploratory cross sectional approach using logistic regression found that public attitudes largely predict which states adopt hate crimes and/or employment discrimination laws. Also relevant are state court decisions and the percentage of Democrats within the legislature. Based on the logistic regression’s classification results, four states were selected for case study analysis: North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Massachusetts. The case studies found that legislators are often reluctant to support transgender issues due to the community’s small size and lack of resources. Additionally, transgender identity’s association with gay rights is both a blessing and curse. In conservative districts, particularly those with large Evangelical communities, there is strong resistance to LGBT rights. However, in more tolerant areas, the association with gay rights advocacy groups can foster transgender inclusion in statutes. Legislators perceive more leeway to support LGBT rights. However, gay activists sometimes remove transgender inclusion for political expediency. As such, the policy core of many LGBT interest groups appears to be gay rights while transgender concerns are secondary items. In the policy domains studied, transgender rights are an extension of gay rights. -

SHNS .: State House News Service

SHNS .: State House News Service statehousenews.com/mobile ☰ Six Lawmakers Named to Draft Final Policing Bill Lead Negotiators: Rep. Claire Cronin, Sen. Will Brownsberger Katie Lannan7/27/20 7:05 PM JULY 27, 2020.....Three senators who helped craft their branch's policing bill will join the Judiciary Committee's House chair, the head of the Massachusetts Black and Latino Legislative Caucus and a former state trooper on a conference committee that will try to reach a House-Senate compromise on police reform. Each branch named its negotiators on Monday. On the Senate side, it's Democrats Sen. William Brownsberger of Belmont and Sen. Sonia Chang-Diaz of Jamaica Plain, and Minority Leader Bruce Tarr, a Gloucester Republican. The House appointed Rep. Claire Cronin, an Easton Democrat who as co-chair of the Judiciary Committee led the House's effort to compile a police reform bill; Springfield Democrat Rep. Carlos Gonzalez, who chairs the Black and Latino Legislative Caucus, and Rep. Timothy Whelan, a Brewster Republican who voted against the bill. Chang-Diaz, the sole member of the Black and Latino Caucus in the Senate, and Brownsberger chaired the working group that developed the Senate's bill. Tarr was the only Republican on that panel. 1/4 Brownsberger and Cronin played leading roles in negotiations on a criminal justice reform package. Those talks lasted for 113 days. The police reform conferees have a much tighter timeline -- Friday marks the last day of formal legislative sessions for the two-year term, though there is a possibility that lawmakers could agree to work beyond that deadline because of the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic. -

Carbon Pricing Lobby Day June 13, 2017 HOUSE

Carbon Pricing Lobby Day June 13, 2017 HOUSE MEETINGS Angelo D’Emilia Andy Gordon: 440-799-3480 Time: 1pm Room: 548 Cory Atkins Staff/#: Andy Gordon 440-799-3480 Time: 1pm Room: 195 Mike Day Leader/#: Janet Lawson, Launa Zimmaro Time: 12:30pm Room: 473f Ruth Balser Leader/#: Mary Jo Maffei 413-265-6390 (staff) Time: 1pm Room: 136 Margaret Decker Leader/#: Marcia Cooper, 617-416-1969 Time: 12pm Room: 166 Christine Barber Leader/#: Grady McGonagle, Time: 10:30am Room: 473f Carolyn Dykema Leader/#: Grace Hall Time: 3:00pm Room: 127 Don Berthiaume Leader/#:Christine Perrin Time: 2pm Room: 540 Lori Ehrlich Leader/#: Rebecca Morris 617-513-1080 (staff) Time: 2pm Room: 167 Paul Brodeur Leader/#: Clyde Elledge Time: 2pm, aide Patrick Prendergast Room: 472 Sean Garballey Leader/#: Time: 2:30pm Room: 540 Gailanne Cariddi Leader/#: Time: 11am Room: 473f Denise Garlick Leader/#: Mary Jo Maffei Time: 2pm Room: 33 Evandro Carvalho Leader/#: Janet Bowser, Cindy Luppi Time: 1:30pm, with aide Luca 617-640-2779 (staff) Room: 136 Leader/#: Joel Wool, 617-694-1141 (staff) Carmine Gentile Time: 2:30pm Mike Connolly Room: 167 Time: 12:30 Leader/#: Eric Lind Room: 33 (basement) Leader/#: Jon Hecht Time: 2:30pm Ed Coppinger Room: 22 Time: 2:30 Leader/#: Room: 26 Leader/#: Vince Maraventano 1 Brad Hill Jay Livingstone Time: 1pm Time: 1:30pm Room: 128 Room: 472 Leader/#: Erica Mattison (staff), Joy Gurrie Leader/#: Kate Hogan Liz Malia Time: 1:30pm Time: 2pm Room: 130 Room: 238 Leader/#: Marc Breslow 617-281-6218 (staff) Leader/#: Amanda Sebert, 630-217-2934 (staff) -

LGBTQ POLICY JOURNAL LGBTQ POLICY JOURNAL at the Harvard Kennedy School

LGBTQ POLICY JOURNAL POLICY LGBTQ LGBTQ POLICY JOURNAL at the Harvard Kennedy School Volume VI, 2015–2016 Trans* Rights: The Time Is Now Featured Articles Trans* Rights: The Time Is Now Rights: The Time Trans* U.S. Department of Justice Agency Facilitates Improved Transgender Community-Police Relations Reclaiming the Gender Framework: Contextualizing Jurisprudence on Gender Identity in UN Human Rights Mechanisms The Forced Sterilization of Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming People in Singapore A Paradigm Shift for Trans Funding: Reducing Disparities and Centering Human Rights Principles VOLUME VI, 2015–2016 Our Mission To inspire thoughtful debate, challenge commonly held beliefs, and move the conversation forward on LGBTQ rights and equality. A Harvard Kennedy School Student Publication | www.hkslgbtq.com LGBTQ POLICY JOURNAL AT THE HARVARD KENNEDY SCHOOL VOLUME VI Trans* Rights: The Time Is Now 2015 - 2016 WWW.HKSLGBTQ.COM All views expressed in the LGBTQ Policy Journal at the Harvard Kennedy School are those of the authors or interviewees only and do not represent the views of Harvard University, the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, the staff of the LGBTQ Policy Journal at the Harvard Kennedy School, the advisory board, or any associates of the journal. © 2016 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. Except as otherwise specified, no article or portion herein is to be reproduced or adapted to other works without the expressed written consent of the editors of the LGBTQ Policy Journal at the Harvard Kennedy School. ISSN# 2160-2980 STAFF Editors-in-Chief Stephen Leonelli Alex Rothman Managing Editors Charles Fletcher Jonathan Lane Editors Danny Ballon Katie Blaisdell Wes Brown Alice Heath Shane Hebel Chaz Kelsh Priscilla Lee Scott Valentine Jenny Weissbourd ADVISORY BOARD Masen Davis Global Action for Trans* Equality Jeff Krehely Louis Lopez US Office of Special Counsel Timothy McCarthy John F. -

Annual Report 2009 from the Director Janet Domenitz, Executive Director

Massachusetts Public interest research GrouP & MassPirG education Fund Annual Report 2009 From The Director Janet Domenitz, Executive Director Dear MASSPIRG supporter, In his historic inauguration speech in January 2009, President Barack Obama said we should not have to make false choices. Specifically, he said we do not have to choose between our security and our ideals. That thought stayed with me throughout the year as we pushed for many important public interest reforms. For example, we should not have to choose between access to, and quality of, our health care. We should not have to decide whether we’re going to bury or burn our waste. And we should not have to choose between borrowing beyond our means or foregoing higher education for our children. In all these examples, and more, what we see is powerful special interests attempting to dictate the debate and present these “choices.” Of course the big insurance companies want us to think the choice is quality or access to health care, because they don’t want to submit to the sorely needed reforms that would make them more transparent, accountable and fair. The landfill and incinerator lobby envisions a future in which we burn more waste or bury it in landfills. They are lobbying hard against the reduce, reuse, recycle advocates like us, who can see an entirely different future for Massachusetts simply by rejecting the status quo and embracing common sense measures that don’t line the pockets of the huge waste companies. I could go on—but the point is, our agenda is more than the sum of its parts. -

Offices to Be Filled at the 2006 General Election

ELECTIONS DIVISION OFFICE OF SECRETARY OF STATE OFFICES TO BE FILLED AT THE NOVEMBER 4, 2014 GENERAL ELECTION United States Senator Term: 6 Years 1-03-15 - 1-3-2021 Incumbent: SAXBY CHAMBLISS US REPRESENTATIVE TERM: 2 YEARS 1-3-15- 1/3/2017 FIRST CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Incumbent: JACK KINGSTON SECOND CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Incumbent: SANFORD BISHOP THIRD CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Incumbent: LYNN WESTMORELAND FOURTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Incumbent: HANK JOHNSON, JR. FIFTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Incumbent: JOHN LEWIS SIXTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Incumbent: TOM PRICE SEVENTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Incumbent: ROB WOODALL EIGHTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Incumbent: AUSTIN SCOTT NINTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT 1 ELECTIONS DIVISION OFFICE OF SECRETARY OF STATE Incumbent: DOUG COLLINS TENTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Incumbent: PAUL BROUN ELEVENTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Incumbent: PHIL GINGREY TWELFTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Incumbent: JOHN BARROW THIRTEENTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Incumbent: DAVID SCOTT FOURTEENTH CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Incumbent: TOM GRAVES GOVERNOR Term: 4 Years 1-12-2015 – 1-14-2019 Incumbent: NATHAN DEAL LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR Term: 4 Years 1/12-2015 – 1-14-2019 Incumbent: CASEY L. CAGLE SECRETARY OF STATE Term: 4 Years 1/12-2015 – 1-14-2019 Incumbent: BRIAN KEMP ATTORNEY GENERAL Term: 4 Years 1/12-2015 – 1-14-2019 Incumbent: SAMUEL L. OLENS STATE SCHOOL SUPERINTENDENT Term: 4 Years 1/12-2015 – 1-14-2019 Incumbent: JOHN D. BARGE 2 ELECTIONS DIVISION OFFICE OF SECRETARY OF STATE COMMISSIONER OF INSURANCE Term: 4 Years 1-12/2015 -1/14/2019 Incumbent: RALPH T. HUDGENS COMMISSIONER OF AGRICULTURE Term: 4 Years 1-12/2015 -1/14/2019 Incumbent: GARY BLACK COMMISSIONER OF LABOR Term: 4 Years 1-12/2015 -1/14/2019 Incumbent: MARK BULTER PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSIONERS Term: 6 Years 1-1/2015 -12/31/2020 Incumbent: H.