ECONOMISTS INCORPORA TED Appendix B: a Statistical Model of Television Network License Fees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BCE Inc. 2015 Annual Report

Leading the way in communications BCE INC. 2015 ANNUAL REPORT for 135 years BELL LEADERSHIP AND INNOVATION PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OUR GOAL For Bell to be recognized by customers as Canada’s leading communications company OUR STRATEGIC IMPERATIVES Invest in broadband networks and services 11 Accelerate wireless 12 Leverage wireline momentum 14 Expand media leadership 16 Improve customer service 18 Achieve a competitive cost structure 20 Bell is leading Canada’s broadband communications revolution, investing more than any other communications company in the fibre networks that carry advanced services, in the products and content that make the most of the power of those networks, and in the customer service that makes all of it accessible. Through the rigorous execution of our 6 Strategic Imperatives, we gained further ground in the marketplace and delivered financial results that enable us to continue to invest in growth services that now account for 81% of revenue. Financial and operational highlights 4 Letters to shareholders 6 Strategic imperatives 11 Community investment 22 Bell archives 24 Management’s discussion and analysis (MD&A) 28 Reports on internal control 112 Consolidated financial statements 116 Notes to consolidated financial statements 120 2 We have re-energized one of Canada’s most respected brands, transforming Bell into a competitive force in every communications segment. Achieving all our financial targets for 2015, we strengthened our financial position and continued to create value for shareholders. DELIVERING INCREASED -

The Economic Framework for Assessing Comcast's Exclusionary Conduct

-77- FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION A. The Economic Framework for Assessing Comcast's Exclusionary Conduct 122. Antitrust economics considers exclusionary conduct to be anticompetitive if it impairs a rival's efficiency or its ability to impose price discipline. Such conduct can occur by raising a rival's costs, by degrading a rival's quality of service,256 or by depriving rivals of economies of scale.257 Anticompetitive effects may be realized regardless of whether the rival is driven out of the market entirely;258 they require that the rival faces increasing marginal costs or large upfront costs or both. If the conduct forces the rival to operate on a higher portion of its marginal cost curve, then such conduct would achieve partial foreclosure, and the rival would not be able to constrain prices as effectively. In the extreme case, when the conduct prevents the rival from covering its average variable costs, the conduct would induce exit and thereby achieve complete foreclosure. 123. Exclusionary strategies can take several forms, and such strategies can be used to extend monopoly power from one market into another, or to maintain monopoly power in a !pven market. When the markets in question are vertically aligned, exclusionary conduct is referred to as "vertical restraints," and the effect of such conduct is called "vertical foreclosure.',259 Because regional sports programming, national sports programming, local broadcast affiliates, and online programming are inputs in the production process of video 256. See Steven C. Salop & David T. Scheffman, Cost-Raising Strategies, 36 J. IND. ECON. 19 (1987). 257. See, e.g., Richard A Posner, Vertical Restraints and Antitrust Policy, 72 U. -

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2006-620

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2006-620 Ottawa, 9 November 2006 The Sports Network Inc. Across Canada Application 2006-0694-9 Broadcasting Public Notice CRTC 2006-79 22 June 2006 Multiple feeds approved In this decision, the Commission approves an application by The Sports Network Inc. to amend the broadcasting licence for the English-language specialty programming undertaking known as TSN, in order to permit the delivery of multiple feeds of its existing programming service to individual broadcasting distribution undertakings on a digital- only basis. Background 1. In Complaint by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation concerning the simultaneous distribution of multiple feeds of The Sports Network, Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2006-197, 23 May 2006 (Decision 2006-197), the Commission determined that The Sports Network Inc. (TSN Inc.) required explicit authorization to permit separate feeds of The Sports Network (TSN) to be distributed simultaneously by broadcasting distribution undertakings (BDUs). 2. In Decision 2006-197, the Commission indicated that it was prepared to consider an application from TSN Inc. to authorize the simultaneous distribution by BDUs of separate feeds of TSN, in a single region, on a digital-only basis. 3. The present application was filed pursuant to Decision 2006-197. The application 4. The Commission received an application by TSN Inc. to amend the broadcasting licence of the national, English-language specialty programming undertaking known as TSN, by amending condition 1(d) of its licence which reads: (d) The licensee may distribute separate regional programming in place of its national service to affiliated distribution undertakings provided that the hours devoted to such regional programming do not exceed 10% of the licensee’s quarterly program schedule. -

Ispeed Channel Guide

Channel Packages IPTV Channels $9.95/month EPG1 Full Name Channel Name Format 3 CBC-HD CBC-HD HD 4 Komo-HD Komo-HD HD 5 Knowledge Network KNOW SD 6 CHEK-HD CHEK HD 7 CBCF-HD CBCF-HD HD 8 OMNI-HD OMNI-HD HD 9 CTV1-HD CTV1-HD HD 11 Global-HD Global-HD HD 12 CTV Two HD CTV2-HD HD 13 CityTV-HD CityTV-HD HD 15 KIRO-HD KIRO-HD HD 16 King-HD King-HD HD 30 Kong-HD Kong-HD HD 31 Q13FOX Q13FOX SD 44 KCTS-HD KCTS-HD HD 54 KBTC-HD KBTC-HD HD 170 KCPQ KCPQ HD 301 Movies! Movies! SD 302 Sports Sports SD 303 SUR SAGAR SURSAGR SD 354 KIRO-SD KIRO-SD SD 355 Create Create SD 356 AnTV AnTV SD 450 KOMO-SD KOMO-SD SD 483 King-SD King-SD SD 485 Kong-SD Kong-SD SD 486 MeTV MeTV SD 501 CRTV CRTV SD 502 Weather Weather SD 518 AAT AAT SD 580 KSTW-D1 KSTW-D1 SD 581 KSTW-D3 KSTW-D3 HD 582 MHZ MHZ SD 586 TVW TVW HD 590 KZJO KZJO SD 670 KTBW-D4 KTBW-D4 SD 671 KRUM-LD KRUM-LD SD 676 AZTECA AZTECA SD 683 KSTW-D2 KSTW-D2 SD 684 KSTW-D5 KSTW-D5 SD 694 KCBC KCBC HD 695 KUNS-1 KUNS-1 HD 696 KUNS-2 KUNS-2 HD Total No. of Channels 43 Basic Channels (includes the above 43 IPTV channels) $29.95/month EPG1 Full Name Channel Name Format 2 ABC Seattle HD ABCWHD HD 10 JoyTV10-HD CHNU-DT HD 17 CTV News Channel CTVNC SD 18 The Weather Network TWN SD 19 W Network West W WEST SD 20 Miracle Network MRCLE SD 23 The Sports Network (TSN) TSN SD 24 MuchMusic MUCH SD 25 YTV West YTVW SD 26 CBC News Network CBCNW SD 27 PBS Seattle (KCTS) PBSS SD 28 FOX Seattle HD FOXWHD HD 29 Home and Garden TV (HGTV) HGTV SD 35 M3 M3 SD 43 Treehouse TREEHS SD 52 The Food Network FOOD SD 53 Knowledge HD KNOWHD -

NR 2017-05-11 Fandom Sports Lead Sponsor of James Duthie's Rubber

FanDom Sports Signed as Lead Sponsor of James Duthie's Rubber Boots Podcast May 11, 2017 CSE: FDM OTC: FDMSF FRANKFURT: TQ42 Santa Monica, California – May 11, 2017, FanDom Sports Media Corp. (CSE: FDM) (OTC: FDMSF) (FRANKFURT: TQ42) (“FanDom Sports” or the “Company”) is pleased to announce the Company is the lead sponsor for sportscaster James Duthie's Rubber Boots Podcast. The Rubber Boots Podcast is an all-new podcast where TSN's (The Sports Network) James Duthie is joined by TSN staffers Lester McLean, Sean 'Puffy' Cameron and a special guest each episode to chat about daily sports and just about anything else. The podcast has a large audience of listeners from across North America. You can subscribe and listen to the full podcast at: iTunes / SoundCloud / Google Play / tsn.ca/Duthie. About James Duthie James Duthie is a Canadian sportscaster for TSN. He is currently the host of TSN Hockey, as well as The Grey Cup, The Super Bowl, The Masters, and the new James Duthie Rubber Boots Podcast. In the past, he has hosted CFL Live, NBA on TSN, SportsCentre, and hosted the 2010 and 2012 Olympics on CTV, He has a bachelor's degree in journalism from Carleton University. Duthie has received 3 Gemini Awards and 2 Canadian Screen Awards for Best Sportscaster in Canada for his various roles. Before moving to TSN in 1998, he worked at VTV in Vancouver and CJOH, the CTV affiliate in Ottawa. At CTV Ottawa, he won an International Edward R. Murrow Award for news reporting. Duthie is the author of three best-selling books: The Guy On The Left, The Day I Almost Killed Two Gretzky's, and They Call Me Killer. -

Baseball in Canada

Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 4 Fall 2000 Baseball in Canada Samuel R. Hill Scocan RSA Limited Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Hill, Samuel R. (2000) "Baseball in Canada," Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies: Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls/vol8/iss1/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baseball in Canada SAMUEL R. HILL* INTRODUCTION Baseball scholars and historians have long accepted that Abner Doubleday did not invent baseball in Cooperstown, New York in 1839.' Doubleday's baseball legend survives, however, as part of baseball folklore; Americans would likely deride the suggestion that a foreign country created baseball. Yet, Canadians recorded a "baseball" game played in 1838 in Beachville, Ontario.' Does the Canadian record debunk the Doubleday baseball legend? The answer, in all likelihood, is no. The modem-day game of baseball most resembles the form of baseball developed in New York in the early nineteenth century.' Canadian baseball, however, developed on a parallel and often intertwined path with that of its American counterpart, and played an instrumental role in shaping baseball as we know it today. -

Channel Lineup

Channel Lineup # Channel Light Premium Ultimate Themes Resolution Wi-Fi* Pause Restart Lookback PVR 201 A&E HD 181 ABC Boston HD 189 ABC Seattle - KOMO HD 311 ABC SPARK Kids HD 611 Adult Swim HD 601 AMC HD 160 AMI-audio HD 162 AMI-télé HD 161 AMI-tv HD 501 Animal Planet HD 253 APTN East SD 153 ARTV HDTV En français HD 502 BBC Earth Knowledge HD 535 BBC First Lifestyle HD Black Entertainment 212 Lifestyle HD Television Business News 361 News HD Network Bloomberg Cable Public Affairs 382 HD (French) Cable Public Affairs 381 HD Channel 261 Canal D En français HD 309 Cartoon Network Kids HD # Channel Light Premium Ultimate Themes Resolution Wi-Fi* Pause Restart Lookback PVR 354 CBC News Network News HD 115 CBC Ottawa HD 116 CBC Toronto HD 119 CBC Vancouver HD 118 CBC Windsor HD 182 CBS Boston HD 190 CBS Seattle - KIRO HD 136 CHCH Hamilton HD 140 Citytv HD 802 CMT HD 359 CNBC News SD 352 CNN HD News HD 269 Cooking Channel Lifestyle HD 532 Cottage Life Knowledge HD 124 CP24 HD Crave + 641 Crave1 Movies + HBO HD with STARZ Crave + 642 Crave2 Movies + HBO HD with STARZ Crave + 643 Crave3 Movies + HBO HD with STARZ Crave + 644 Crave4 Movies + HBO HD with STARZ 221 Crime + Investigation Lifestyle HD 214 CTV Comedy HD # Channel Light Premium Ultimate Themes Resolution Wi-Fi* Pause Restart Lookback PVR 254 CTV Drama HD 131 CTV Kitchener HD 270 CTV Life Lifestyle HD 351 CTV News Channel News HD 126 CTV Ottawa HD 224 CTV Sci-Fi HD 128 CTV Toronto - CFTO HD 129 CTV Two Barrie - CKVR HD CTV Two London - 132 HD CFPL CTV Two Ottawa - 127 HD CHRO 133 CTV -

Fibre Optic TV Winter 2020 Channel Lineup

Fibre Optic TV winter 2020 Channel lineup 100 4K FR IHR 4K Include with Basic Informative channel about Internet Haut-Richelieu and their services. 101 HD FR ICI Radio-Canada Montréal Include with Basic ICI Radio Canada is a national french television channel, unique with high quality productions, which will entertain your whole family. 102 HD FR TVA Montréal Include with Basic TVA is a private network running for the past 40 years that offers the most popular programs: variety shows, dramatic series, news and films, 103 HD FR V Montréal Include with Basic V Télé offers an original programmation that will captivate your family. 104 HD FR Télé-Québec Include with Basic Télé Québec: shows, movies, games, short films, documentaries for the whole family. 105 HD FR TV5 Include with Basic TV5 Canada is part of the mondial consortium TV5. You will find popular shows from France Television, ARTE France, RTBF from Belgium, RTS from Switzerland, Radio-Canada, Télé-Québec and original productions, 106 HD FR Télévision Française Ontarie 1,00 | Include with Basic plus TFO is the provincial francophone channel of Ontario. A high quality and educative programmation. 107 SD FR Saint-Pierre et Miquelon 1èr 1,00 | Include with Basic plus St-Pierre et Miquelon Première is the only oversea francophone channel. Experience France and the small community of Saint-Pierre et Miquelon. This channel broascasts over the air from the french territory south of Newfoundland Page 1/26 Fibre Optic TV winter 2020 Channel lineup 109 SD FR TVHR Include with Basic Télévision du Haut-Richelieu is an exclusive and local oriented station, proudly distributed by IHR. -

CHANNEL LISTINGS - WINNIPEG Effective February 17, 2011

CHANNEL LISTINGS - WINNIPEG Effective February 17, 2011 59 WSBK - Boston Superstation 146 Sportsnet - Ontario 225 Sportsnet One HD BASIC 60 KTLA - Los Angeles Superstation 147 TSN 2 227 National Geographic HD 2 CBWT - CBC Winnipeg 61 WGN - Chicago Superstation 148 NBA TV Canada 228 Discovery World HD 3 KGFE - PBS Grand Forks 62 WPIX - New York Superstation 149 The Fight Network 229 History HD 4 WCCO - CBS - Minneapolis 65 Telelatino 151 GOL TV 230 Oasis HD 5 CTV-W - TV Winnipeg 67 Teletoon - Retro 152 WFN - World Fishing Network 233 A&E HD 6 KARE - NBC Minneapolis 81 WTVS - PBS Detroit 153 ESPN - Classic Canada 234 Showcase HD 7 WDAZ - ABC Grand Forks 86 The Shopping Channel (SHOP) 156 Fox Sportsworld 235 HDNet 8 CHMI - CityTV Winnipeg 87 Horseracing / University Channel 158 NHL Network 236 TLC HD 9 Shaw TV 89 TFO 159 Sportsnet One 237 Encore HD 10 CBWFT - CBC French Winnipeg 90 MSNBC 160 Salt and Light 238 WGN HD 11 Joytv 11 - CIIT Winnipeg 91 Cosmopolitan TV 166 Grace TV 239 AMC HD 12 CKND - Global Winnipeg 92 VIVA 167 EWTN - Eternal Word Television 13 TSN - The Sports Network 93 National Geographic 168 One: Body, Mind & Spirit Channel ON DEMAND 22 YTV 143 CNBC 169 Biography 1, 299 VOD Movie Trailers 45 CBC News Network / Voiceprint 144 The Golf Channel 170 BookTelevision 300 HD PPV Events 46 CTV Newsnet 150 NFL Network 171 Twist TV 301 HD PPV Events 47 Sportsnet - West 155 Game TV 172 Documentary Channel 302 Sportsnet One Hockey HD 48 Environment Channel 157 Big Ten 173 Fashion Television 303-308 HD PPV Sports 49 WUHF - FOX Rochester -

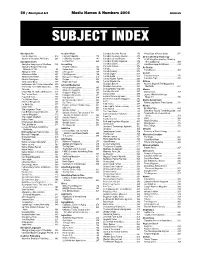

Subject Index

50 / Aboriginal Art Media Names & Numbers 2006 Animals SUBJECT INDEX Aboriginal Art Acadian Affairs Canadian Ayrshire Review. 270 Wheat Oats & Barley Guide. 371 Inuit Art Quarterly . 312 L’Acadie Nouvelle. 173 Canadian Guernsey Journal . 273 Air Conditioning Technology Journal of Canadian Art History. 381 Le Moniteur Acadien. 241 Canadian Jersey Breeder . 274 HPAC Magazine (Heating Plumbing Aboriginal Issues Le Ven’D’est . 365 Canadian Poultry Magazine. 276 Air Conditioning) . 309 Aboriginal Languages of Manitoba . 194 Accounting Canadian Swine . 277 Inter-Mécanique du Bâtiment . 312 Cannabis Culture . 279 Aboriginal Peoples Television Beyond Numbers . 264 Air Quality Canola . 279 Network (APTN) . 84 Bottom Line . 266 TransMission. 359 Aboriginal Times . 183 CAmagazine . 269 Canola Country. 279 Aircraft Akwesasne Notes . 227 CGA Magazine . 280 Canola Digest . 279 Canadian Aviator . 270 Alberta Native News. 183 Management Magazine . 320 Canola Guide . 279 Canadian Flight. 386 Alberta Sweetgrass. 183 Outlook . 334 Central Alberta Farmer. 280 Anishinabek News . 199 Report on Fraud . 346 Central Alberta Life. 280 Airlines Charolais Banner . 281 Above & Beyond (The Magazine of Batchewana First Nation Newsletter. 200 Activism/Radicalism Charolais Connection. 281 the North) . 254 CHFG-FM, 101.1 mHz (Chisasibi). 153 Action Speaks Louder . 385 Le Cooperateur Agricole . 286 Chiiwetin . 229 Adbusters Magazine. 255 Alberta Country Life In BC . 287 CHON-FM, 98.1 mHz (Whitehorse) . 125 Briarpatch Magazine. 266 AlbertaViews . 257 Dairy Contact . 288 The Eastern Door . 231 Canadian Dimension . 271 Legacy: Alberta’s Heritage Eastern Ontario Agrinews . 292 Esquimalt News . 177 New Socialist. 328 Magazine . 316 Eco-Farm & Garden Magazine . 292 First Nations Drum . 177 Our Schools/Our Selves. 334 Alberta Government FAC’s . -

Bell Media Inc. Various Locations and Across Canada

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2017-149 PDF version References: 2016-225, 2016-225-1, 2016-225-2, 2016-225-3 and 2016-225-5 Ottawa, 15 May 2017 Bell Media Inc. Various locations and across Canada Application 2016-0012-2, received 11 January 2016 Public hearing in the National Capital Region 28 November 2016 Bell Media Inc. – Licence renewals for English-language television stations and services The Commission renews the broadcasting licences for the various English-language television stations and services that will form the Bell Media Group in the next licence term, from 1 September 2017 to 31 August 2022. In addition, the Commission renews the broadcasting licences for various television services that are not included in the Bell Media Group in the next licence term, from 1 September 2017 to 31 August 2022. For Bell TV On Demand (terrestrial pay-per-view service) and Bell TV On Demand (direct-to- home pay-per-view service), the Commission revokes the current broadcasting licences, effective 31 August 2017. New broadcasting licences will be issued for the services, which will take effect 1 September 2017 and expire 31 August 2022. Application 1. Bell Media Inc. (Bell Media), on behalf of itself and the licensees listed in Appendices 1 and 2 to this decision, filed an application to renew the broadcasting licences for the English- language television stations, discretionary services and other services set out in the appendices. 2. Specifically, Bell Media is seeking the renewal of the broadcasting licences for the CTV and CTV Two television stations across the country, the satellite-to-cable services CTV Two Alberta and CTV Two Atlantic, several discretionary services and the on-demand services. -

Baseball in Canada Samuel R

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Indiana University Bloomington Maurer School of Law Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 4 Fall 2000 Baseball in Canada Samuel R. Hill Scocan RSA Limited Follow this and additional works at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Hill, Samuel R. (2000) "Baseball in Canada," Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies: Vol. 8: Iss. 1, Article 4. Available at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ijgls/vol8/iss1/4 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baseball in Canada SAMUEL R. HILL* INTRODUCTION Baseball scholars and historians have long accepted that Abner Doubleday did not invent baseball in Cooperstown, New York in 1839.' Doubleday's baseball legend survives, however, as part of baseball folklore; Americans would likely deride the suggestion that a foreign country created baseball. Yet, Canadians recorded a "baseball" game played in 1838 in Beachville, Ontario.' Does the Canadian record debunk the Doubleday baseball legend? The answer, in all likelihood, is no. The modem-day game of baseball most resembles the form of baseball developed in New York in the early nineteenth century.' Canadian baseball, however, developed on a parallel and often intertwined path with that of its American counterpart, and played an instrumental role in shaping baseball as we know it today.