Black Labor and the Deep South in Hurston's the Great Day And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bennett with Photos

Corbies and Laverocks and the Four and Twenty Blackbirds: The Montgomerie Legacy to Folklore and the Mother Tongue MARGARET BENNETT “The State of Play” was the title of a memorable conference held in Sheffield in 1998, with Iona Opie as the keynote speaker. Her long collaboration with her husband, Peter, and their book, The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren, had been the inspiration of those who filled the hall, and for some it marked a milestone in their lives – as John Widdowson humorously said, it had seduced him into folklore.1 While the title of Dr Opie’s talk was “A Lifetime in the Playground” she began by explaining that the playground was not actually the starting point for their work; it was, rather, in books and library collections. The Opies shared a fascination with the history and provenance of nursery rhymes and when their seven year project led to the publication of The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes in 1951, the level of interest and success of the book was a turning point: “We decided to do something that had never been done before. We decided to ask the school children themselves …” The scale of their collecting, from Land’s End to Cape Wrath, their approach to the fieldwork, and the duration of their work “had never been done before” in Britain, though American folklorists had been audio-recording in playgrounds and streets since the 1930s.2 Foremost among them was Herbert Halpert, who later introduced his students (of which I was one) to the work of Iona and Peter Opie in his Folklore classes at Memorial University of Newfoundland – The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren (1959) was on the Required Reading List, to be purchased from the MUN Bookstore. -

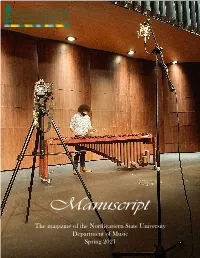

Manuscript Newsletter, Spring 2021 Edition

Manuscript The magazine of the Northeastern State University Department of Music Spring 2021 Contents 2 Welcome from the Chair Features 3 Guest Artists 5 NSU @ OkMEA 6 New Student Lounge & Opera Workshop 7 Green Country Jazz Festival 9 “Can’t stop the Music” (AKA NSU Music during a global pandemic) 11 Announcement of a new music degree 12 Student News 13 Alumni Feature 14 In Memorium 15 Faculty News 17 Endowments, Scholarships, & Donors Musicians: we are the most romantic of all artists. We believe in, and chase the illusive, intoxicating, unseen magic/beauty that exists in the universe. We are conduits for this magic/ beauty that has the ability to stir emotions that are fundamental to what it means to be human and alive. Here’s to us all....! - Dr. Ron Chioldi Welcome FROM THE CHAIR Spring 2021 marks the end of an academic year unlike any other. It was difficult. It was certainly stressful. So many modifications were made to our normal operating procedures due to the pandemic. Some of these modifications will inform how we operate in the future. Others, I hope we never have to implement ever again. Our faculty, staff, and students were resilient in the face of highly pressurized circum- stances. I want to thank them for their grace, adaptability, and understanding as things constantly changed. Early on in the pandemic, the performing arts were singled out as being particularly risky for infection. We took measures to ensure the safety of our faculty, staff, and students as best we could under state, local, and university protocols. -

Folklore: an Emerging Discipline — Selected Essays of Herbert Halpert

Document generated on 09/26/2021 9:58 p.m. Ethnologies Folklore: An Emerging Discipline — Selected Essays of Herbert Halpert. By Martin Lovelace, Paul Smith and J. D. A. Widdowson, eds. (St. John’s: Memorial University of Newfoundland Folklore and Language Publications, 2002. Pp. xxi + 398, ISBN 0-88901-335-7) Cory W. Thorne Littératie Literacy Volume 26, Number 1, 2004 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/013348ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/013348ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Association Canadienne d'Ethnologie et de Folklore ISSN 1481-5974 (print) 1708-0401 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Thorne, C. W. (2004). Review of [Folklore: An Emerging Discipline — Selected Essays of Herbert Halpert. By Martin Lovelace, Paul Smith and J. D. A. Widdowson, eds. (St. John’s: Memorial University of Newfoundland Folklore and Language Publications, 2002. Pp. xxi + 398, ISBN 0-88901-335-7)]. Ethnologies, 26(1), 235–238. https://doi.org/10.7202/013348ar Tous droits réservés © Ethnologies, Université Laval, 2004 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ REVIEWS / COMPTES-RENDUS REVIEWS / COMPTES-RENDUS Folklore: An Emerging Discipline — Selected Essays of Herbert Halpert. By Martin Lovelace, Paul Smith and J. -

Norway's Jazz Identity by © 2019 Ashley Hirt MA

Mountain Sound: Norway’s Jazz Identity By © 2019 Ashley Hirt M.A., University of Idaho, 2011 B.A., Pittsburg State University, 2009 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Musicology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Musicology. __________________________ Chair: Dr. Roberta Freund Schwartz __________________________ Dr. Bryan Haaheim __________________________ Dr. Paul Laird __________________________ Dr. Sherrie Tucker __________________________ Dr. Ketty Wong-Cruz The dissertation committee for Ashley Hirt certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: _____________________________ Chair: Date approved: ii Abstract Jazz musicians in Norway have cultivated a distinctive sound, driven by timbral markers and visual album aesthetics that are associated with the cold mountain valleys and fjords of their home country. This jazz dialect was developed in the decade following the Nazi occupation of Norway, when Norwegians utilized jazz as a subtle tool of resistance to Nazi cultural policies. This dialect was further enriched through the Scandinavian residencies of African American free jazz pioneers Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, and George Russell, who tutored Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek. Garbarek is credited with codifying the “Nordic sound” in the 1960s and ‘70s through his improvisations on numerous albums released on the ECM label. Throughout this document I will define, describe, and contextualize this sound concept. Today, the Nordic sound is embraced by Norwegian musicians and cultural institutions alike, and has come to form a significant component of modern Norwegian artistic identity. This document explores these dynamics and how they all contribute to a Norwegian jazz scene that continues to grow and flourish, expressing this jazz identity in a world marked by increasing globalization. -

Fifty-Ninth Annual Meeting of the American Folklore

FIFTY-NINTH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN FOLKLORE SOCIETY The fifty-ninth annual meeting of the American Folklore Society was held at the Hotel Tuller, Detroit, Michigan, on December 28-29, 1Q47. Meetings were held in conjunction with the Modern Language Association of America. The President, Joseph M. Carrire, presided. The following papers were presented: Horace P. Beck, "The Animal That Can't Lie Down"; Levette J. Davidson, "Hermits of the Rockies"; Robert E. Gard, "To- ward a Folklore Theatre"; GertrudeProkosch Kurath, "Mexican Moriscas:A Prob- lem in Dance Acculturation"; Duncan Emrich, "The London and Paris Folklore Conferences"; Jane I. Zielonko, "The Nature and Causes of Ballad Variation"; Haldeen Braddy, "Pancho Villa, Folk Hero of the Mexican Border"; Herbert Halpert, "Our Approach to American-EnglishFolklore"; Thelma James, "Mosar- dine-jo Tales Found in Detroit." Following the annual banquet and the Presidential Remarks, the International Institute of Detroit, under the direction of Alice L. Sickels, presented a program of songs and dances, in costume, of the various ethnic groups in Detroit. At the business meeting officersfor the year 1948 were elected. (These are printed in full on Cover II of the Journal.) At the meeting of the Council the following reports were read and approved: Secretary's Report The Secretary reports the membershipof the Society as follows: 1947 1946 1945 Honorary Members 7 6 6 Life Members 10 8 8 Old Members 760 648 577 New Members 141 154 135 Total Active Members 911 8io 690 During the year 42 members were removed from the rolls because of non-payment of dues, resignations, or death; 64 were dropped in 1946, and 36 in 1945. -

Print This Article

The Power of Song as the Voice of the People Margaret Bennett The Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Scotland There are few political speeches that effectively match the power of a song in keeping alive issues of social justice or freedom. In the seventeenth century, Scottish politician Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun proclaimed: ‘If a man were permitted to make all the ballads, he need not care who should make the laws of a nation.’i As in Fletcher’s day, there is no telling if a song of protest will bring about change – nevertheless, it is still the most powerful tool to give voice to those with enough conviction to take a stand. Of equal importance, songs are our most harmonious and peaceful ‘weapons’, effective outside the context of conflict as well as on the picket line or demonstration. It was in the spirit of taking a stand that Festival 500 was ‘purposely conceived and initiated in response to the threat to Newfoundland’s culture by the enforced closure of the cod fishery in 1992.’ As every Newfoundlander knows, ‘[the cod] fishery was not only a mainstay of the province's economy, but the raison d'être for European settlement. In fact, it was the social and economic engine of our society. Its closure was a devastation to our society…’ And in ‘Newfoundland and Labrador, [singing] has historically been an integral part of community life – a way of celebrating, mourning, documenting events, telling the stories.’ In 1968, when I first arrived in Newfoundland as a student, I felt instantly at home to find that singing had a part in every occasion, be it in kitchen, the student common room, or anywhere else. -

The Assimilation of American Jazz in Trance, 1917-1940

le hot the assimilation of american jazz in trance, 1917-1940 William h. kenney iii The assimilation of American jazz music in France, an instance of the cultural transmission of an emerging American musical art, began at the time of World War I. Within the subsequent history of jazz in France lies the tale of the progressive mastery of the two principles of improvisation and rhythmic swing and the modification of American sounds to suit the particular cultural terrain of France between the two World Wars. The process was eased by the obvious fact that France already contained, indeed originated in some cases, the basics of western music: instrumental definitions, chromatic and diatonic scales and the myriad chords from which they were constructed. Still, the principles of melodic and particu larly harmonic improvisation were little known in France as was the surprising phenomenon of rhythmic swing so that when early jazz arrived in that country French musicians knew most of the vocabulary of jazz without knowing how to make jazz statements. A small number of French musicians learned to "sing" with a swing and in the process created their own "école française de jazz." Ragtime and the musical precursors of jazz were carried from the U.S.A. to France by military bands sent by the American government in 1917. The most famous was the 369th Infantry Regiment's Hell Fighters Band, an all-Black outfit organized and led by James Reese Europe. Europe was a pioneer of ragtime in New York City where he had organized 0026-3079/84/2501-0005S01.50/0 5 concerts of Black music, headed the famous Clef Club, and accompanied Irene and Vernon Castle's introduction of the foxtrot in America. -

The Memorial University of Newfoundland Folklore and Language Archive

THE MEMORIAL UNIVERSITY OF NEWFOUNDLAND FOLKLORE AND LANGUAGE ARCHIVE By Patricia Fulton Archivist www.mun.ca/folklore/munfla.htm The Memorial University of Newfoundland later in his career when he was invited to teach Folklore and Language Archive (MUNFLA) at Memorial University: is Canada's leading repository for recorded and collected items of Newfoundland and ...the people of Newfoundland Labrador folklore, folklife, language, oral have been settled in a comparatively history and popular culture. Founded in 1968, isolated area for a long period of time the Archive, under the direction of Herbert and have developed a unique cultural Halpert (b. Manhattan, 1911-d. St. John's, response to their environment. We 2000), began building on the course have in this province one of the last assignments and materials from fieldwork areas in the English-speaking world expeditions collected during his previous six where customs and practises [sic] years as a university faculty member. The survived long after they died out Archive has since amassed 600fonds, 40,000 elsewhere. The folklorist can still audio recordings, 800 video recordings, learn ftom people who observed these 16,000 manuscripts, 20,000 photographs, customs, how they were performed 1,500 printed documents, 500 oversized and what they meant.' documents, 4,000 commercial discs, 50 course collections, and numerous cultural artifacts Halpert, who had already done and other media. groundbreaking folklore fieldwork and scholarship in the United States, embarked on Described as Herbert Halpert's "crowning a series of summer expeditions with his fellow achievement,"' MUNFLA stands as testimony faculty member, the linguist John D.A. -

Society for Ethnomusicology 59Th Annual Meeting, 2014 Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology 59th Annual Meeting, 2014 Abstracts Young Tradition Bearers: The Transmission of Liturgical Chant at an then forms a prism through which to rethink the dialectics of the amateur in Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church in Seattle music-making in general. If 'the amateur' is ambiguous and contested, I argue David Aarons, University of Washington that State sponsorship is also paradoxical. Does it indeed function here as a 'redemption of the mundane' (Biancorosso 2004), a societal-level positioning “My children know it better than me,” says a first generation immigrant at the gesture validating the musical tastes and moral unassailability of baby- Holy Trinity Eritrean Orthodox Church in Seattle. This statement reflects a boomer retirees? Or is support for amateur practice merely self-interested, phenomenon among Eritrean immigrants in Seattle, whereby second and fails to fully counteract other matrices of value-formation, thereby also generation youth are taught ancient liturgical melodies and texts that their limiting potentially empowering impacts in economies of musical and symbolic parents never learned in Eritrea due to socio-political unrest. The liturgy is capital? chanted entirely in Ge'ez, an ecclesiastical language and an ancient musical mode, one difficult to learn and perform, yet its proper rendering is pivotal to Emotion and Temporality in WWII Musical Commemorations in the integrity of the worship (Shelemay, Jeffery, Monson, 1993). Building on Kazakhstan Shelemay's (2009) study of Ethiopian immigrants in the U.S. and the Margarethe Adams, Stony Brook University transmission of liturgical chant, I focus on a Seattle Eritrean community whose traditions, though rooted in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, are The social and felt experience of time informs the way we construct and affected by Eritrea's turbulent history with Ethiopia. -

Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination

Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hamilton, John C. 2013. Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11125122 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination A dissertation presented by Jack Hamilton to The Committee on Higher Degrees in American Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of American Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2013 © 2013 Jack Hamilton All rights reserved. Professor Werner Sollors Jack Hamilton Professor Carol J. Oja Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination Abstract This dissertation explores the interplay of popular music and racial thought in the 1960s, and asks how, when, and why rock and roll music “became white.” By Jimi Hendrix’s death in 1970 the idea of a black man playing electric lead guitar was considered literally remarkable in ways it had not been for Chuck Berry only ten years earlier: employing an interdisciplinary combination of archival research, musical analysis, and critical race theory, this project explains how this happened, and in doing so tells two stories simultaneously. -

MUSIC | THEATRE | DANCE 2016 –17 PERFORMANCE SEASON 2 MUSIC | THEATRE | DANCE Oakland.Edu/Mtd

MUSIC | THEATRE | DANCE 2016 –17 PERFORMANCE SEASON 2 MUSIC | THEATRE | DANCE oakland.edu/mtd WELCOME Dear Friends of the Arts, It is my pleasure to invite you to our 2016-17 performance season. With our wide range of offerings featuring students, faculty and renowned guest artists, we have something to please everyone. We hope you will be intrigued and perhaps even try something new. Through our partnership with the Chamber Music Society of Detroit, the Juilliard String Quartet will once again grace our concert stage. This time they will perform with Oakland faculty pianist Tian Tian. Guitarist Celino Romero will also return as part of this series, along with Metropolitan Opera soprano Heidi Grant Murphy, pianist Christopher O’Riley and the Imani Winds. Jazz violinist Regina Carter, the Oakland University artist-in-residence, will return to our stage to perform two different concerts. We also welcome contemporary saxophonist Ben Wendel and his group, and Michael Dease who will perform with our student jazz band. Both are Grammy-nominated artists. This season marks the 20th anniversary of the David Daniels Young Artists Concert, which gives each OU Concerto Competition winner a chance to perform with the Oakland Symphony Orchestra. The Oakland Chorale is preparing for a European tour next summer. At this year’s Chorus and Chorale concerts you can hear the music they will perform while on tour. Resident dance company Take Root returns to share their innovative artistry, along with Eisenhower Dance and a range of concerts that showcase student choreography and dance. OU opera students will present Mozart’s The Magic Flute, and the theatre program will present A Chorus Line and Neil Simon’s Rumors, as part of their Mainstage season. -

Main Artist (Group) Album Title Other Artists Date Cannonball Adderley

Julian Andrews Collection (LPs) at the Pendlebury Library of Music, Cambridge list compiled by Rachel Ambrose Evans, August 2010 Main Artist (Group) Album Title Other Artists Date Cannonball Adderley Coast to Coast Adderley Quintet 1959/62 and Sextet (Nat Adderley, Bobby Timmons, Sam Jones, Louis Hayes, Yusef Lateef, Joe Zawinul) Cannonball Adderley The Cannonball Wes Montgomery, 1960 Adderley Victor Feldman, Collection: Ray Brown, Louis Volume 4 Hayes Nat Adderley Work Songs Wes Montgomery, 1978 Cannonball Adderley, Yusef Lateef Larry Adler Extracts from the film 'Genevieve' Monty Alexander Monty Strikes Ernest Ranglin, 1974 Again. (Live in Eberhard Weber, Germany) Kenny Clare Monty Alexander, Ray Brown, Herb Triple Treat 1982 Ellis The Monty Alexander Quintet Ivory and Steel Monty Alexander, 1980 Othello Molineux, Robert Thomas Jr., Frank Gant, Gerald Wiggins Monty Alexander Ivory and Steel (2) Othello Molineux, 1988 Len Sharpe, Marshall Wood, Bernard Montgomery, Robert Thomas Jr., Marvin Smith Henry Allen Henry “Red” 1929 Allen and his New York Orchestra. Volume 1 (1929) Henry Allen The College Steve Kuhn, 1967 Concert of Pee Charlie Haden, Wee Russell and Marty Morell, Henry Red Allen Whitney Balliett Mose Allison Local Color Mose Allison Trio 1957 (Addison Farmer, Nick Stabulas) Mose Allison The Prestige Various 1957-9 Collection: Greatest Hits Mose Allison Mose Allison Addison Farmer, 1963 Sings Frank Isola, Ronnie Free, Nick Stabulas Mose Allison Middle Class Joe Farrell, Phil 1982 White Boy Upchurch, Putter Smith, John Dentz, Ron Powell Mose Allison Lessons in Living Jack Bruce, Billy 1982 Cobham, Lou Donaldson, Eric Gale Mose Allison Ever Since the Denis Irwin, Tom 1987 World Ended Whaley Laurindo Almeida Laurindo Almeida Bud Shank, Harry quartet featuring Babasin, Roy Bud Shank Harte Bert Ambrose Ambrose and his Various 1983 Orchestra: Swing is in the air Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson Boogie Woogie 1939 Classics Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson, Jimmy Boogie Woogie James F.