Earthmen Bearing Gifts Fredrick Brown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

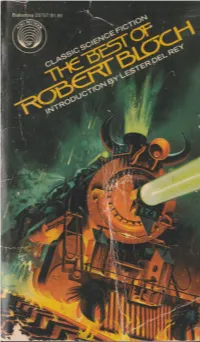

Bloch the Best of Edmond Hamilton Introduction by Leigh Brackett the Best of Leigh Brackett Introduction by Edmond Hamilton *The Best of L

THE STALKING DEAD The lights went out. Somebody giggled. I heard footsteps in the darkness. Mutter- ings. A hand brushed my face. Absurd, standing here in the dark with a group of tipsy fools, egged on by an obsessed Englishman. And yet there was real terror here . Jack the Ripper had prowled in dark ness like this, with a knife, a madman's brain and a madman's purpose. But Jack the Ripper was dead and dust these many years—by every human law . Hollis shrieked; there was a grisly thud. The lights went on. Everybody screamed. Sir Guy Hollis lay sprawled on the floor in the center of the room—Hollis, who had moments before told of his crack-brained belief that the Ripper still stalked the earth . The Critically Acclaimed Series of Classic Science Fiction NOW AVAILABLE: The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum Introduction by Isaac Asimov The Best of Fritz Leiber Introduction by Poul Anderson The Best of Frederik Pohl Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of Henry Kuttne'r Introduction by Ray Bradbury The Best of Cordwainer Smith Introduction by J. J. Pierce The Best of C. L. Moore Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of John W. Campbell Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of C. M. Kornbluth Introduction by Frederik Pohl The Best of Philip K. Dick Introduction by John Brunner The Best of Fredric Brown Introduction by Robert Bloch The Best of Edmond Hamilton Introduction by Leigh Brackett The Best of Leigh Brackett Introduction by Edmond Hamilton *The Best of L. -

Fantasy & Science Fiction V025n04

p I4tk Anniversary ALL STAR ISSUE Fantasi/ and Science Fiction OCTOBER ASIMOV BESTER DAVIDSON DE CAMP HENDERSON MACLEI.SH MATHESON : Girl Of My Dreams RICHARD MATHESON 5 Epistle To Be Left In The Earth {verse) Archibald macleish 17 Books AVRAM DAVIDSON 19 Deluge {novelet) ZENNA HENDERSON 24 The Light And The Sadness {verse) JEANNETTE NICHOLS 54 Faed-out AVRAM DAVIDSON 55 How To Plan A Fauna L. SPRAGUE DE CAMP 72 Special Consent P. M. HUBBARD 84 Science; Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star ISAAC ASIMOV 90 They Don’t Make Life Like They Used To {novelet) ALFRED BESTER 100 Guest Editorial: Toward A Definition Of Science Fiction FREDRIC BROWNS' 128 In this issue . Coming next month 4 F&SF Marketplace 129 Cover by Chesley Bonestell {see page 23 for explanation) Joseph IV. Fcnnan, publisher Avram Davidson, executive editoi: Isaac Asimov, science editor Edzvard L. Forman, managing editoi; The Magasine of Fa^itasy and Science Fiction, Volume 25, No. 4, IVhole No. 149, Oct. 1963. Published monthly by Mercury Press, Inc., at 40c o copy. Annual subscription $4.50; $5.00 in Canada and the Pan American Union; $5.50 in all ether countries. Ptibli- cation office, 10 Ferry Street, Concord, N. FI. Editorial and general mail should be soit ie 347 East 53rd St., Nezv York 22, N. Y. Second Class postage paid at Concord, N. H. Printed in U. S. A. © 1963 by Mercury Press, Inc. All rights, including translations into otJut languages, reserved. Submissions must be accompanied by stamped, self-addressed envelopes the Publisher assumes no responsibility fur return of unsolicited manuscripts. -

Dynatron Is 915 Green Valley Road NW, Albuquerque, NM

This is the grand and have finally reached the magic ^mbe orious fanzine. we I Ah, yes, ; hundredthe issue of a not so grand and gio glorious one THE CONTENTS 3 Writings in the Sand by Roytac 6 One Prson’s View by Mike Kring Cyberpunk: 7 The Pulp Forest by Ed Cox 11 Martians, Go Figure by Dave Locke 14 En Deux Mots by Jack Speer MacCallum 17 The Old Boy’s Syndrome by Danny 0. MacCallum 20 Whither Fandom? by Paul Lagasse ARTWORK: Cover by Atom Art Hoover 2, 10, 16 My thanx to all who contributed to this issue Tackett, dDyYnNaAtTrRoOnN #100. Dynatron is 915 Green Valley Road NW, Albuquerque, NM It is, as it always has been, A Marinated Publication I and is dated December 1991 WRITINGS IN THE SAND 100 issues of DYNATRON. I am tempted to add: "That's not too many." Perhaps it is, though. Both from the point of view of the fans who have read this zine over the years and, mayhap, from the point of view of the editor/publisher. It has been a long time. You could say that in a way it is Buck Coulson's fault. My roots in the science fiction/ fantasy field go back to the 1930s. I was a reader of fantasy from the time I learned to read and read what ever children's fantasy books were Roytac when he first began available. There were not too many. to publish Dynatron. I picked up my first prozine in 1933 (which is also the time I started smoking—is there a connection?) and was instantly hooked. -

Oh, for the Life of an Author's Wife by Elizabeth Charlier Brown, Edited by Chad Calkins, Introduction by Jack Seabrook

Memoir by Elizabeth Charlier Brown (1902-1986), chronicling the first ten years of her marriage to Fredric Brown (1906-1972), author of many classic mystery and science fiction short stories and novels, such as The Fabulous Clipjoint, The Screaming Mimi, Night of the Jabberwock, and What Mad Universe. Oh, for the Life of an Author's Wife by Elizabeth Charlier Brown, Edited by Chad Calkins, Introduction by Jack Seabrook Order the complete book from the publisher Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/9568.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Copyright © 2018 The Estate of Fredric Brown Introduction copyright © 2018 by Jack Seabrook Paperback ISBN: 978-1-63492-700-0 Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-63492-701-7 All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review or scholarly journal. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., St. Petersburg, Florida, U.S.A. Printed on acid-free paper. Chad Calkins [email protected] 2018 First Edition Introduction The fact that you’re reading this introduction probably means that you know that the author referred to in the title of this book is Fredric Brown, one of the best mystery writers of the 1940s and 1950s. He also wrote some great science fiction short stories and novels. A bit of background on Mr. Brown is in order before you start to read his second wife’s memoir, just to help you get your bearings. -

39Th Military Librarians Workshop

39th Military Librarians Workshop "Information Warfare: Librarians on the Frontline" 9-12 October 1995 Combined Arms Research Library Fort Leavenworth, Kansas mm m THIS DOCUMENT IS BEST QUALITY AVAILABLE. THE COPY FURNISHED TO DTIC CONTAINED A SIGNIFICANT NUMBER OF PAGES WHICH DO NOT REPRODUCE LEGIBLY. Information Warfare: Librarians on the Frontline Proceedings of the 39th Annual Military Librarian's Workshop Elaine McConnell & Stephen Brown, editors 9-12 October 1995 Combined Arms Research Library Fort Leavenworth, Kansas Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources. Public s gatheringgarnering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden est.mate or anpther ?^£ °'™' collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway Suite 1204 Arlington VA 22202-4302. and to the Office of Management and Budget. Paperwork Reduction Pr0)ect (0704-0188). Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED 30 October 1996 Conference Proceedings- Final 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Information warfare: librarians on the frontline: Proceed- ings of the Thirty-Ninth Military Librarian's Workshop, 9-12 October 1995 6. AUTHOR(S) Elaine McConnell Stephen Brown, editors 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER USACGSC Combined Arms Research Library USACGSC/CARL 250 Gibbon Avenue Fort Leavenworth, KS 66027-2314 9. -

86'Ed Banned from the Lot. the Term Is in General Use Meaning

86'ed Banned from the lot. The term is in general use meaning "we have no more [ something]" or "to get rid of [something]." There are many 'folk etymologies' ex plaining the origin of the term, but all are dubious. A&S Man "Age and Scale" operator ("guess your age or weight" operator). More com monly known as "Fool the Guesser," the game can be operated as a hanky-pank (q.v .) or any of several other ways. AB Amusement Business, the trade magazine of the outdoor entertainment industry. ABA A commercial "traveler's check," often purchased under assumed names, useful for carrying and transferring large sums of cash without bank or I.R.S. scrutin y. Add-Up Joint, or Add 'Em Up Game where each play (each dart thrown, ball rolled, balloon broken...) scores points that are totaled for the player. In its most d irect form, it is a fair enough game (though it is illegal in some areas as a 'g ame of chance') but it is very similar to the larcenous "razzle dazzle' game whi ch adds a 'build up' feature (q.v.) and cannot be won. Advance Man Employee who handles details such as licenses and sponsors before a carnival arrives in town, and sometimes handles bribes to local officials for le aving the carnival alone. After-Catch Items sold to show patrons after they have paid their admission and seen the show. After-Show Blowoff (q.v.) Afterpiece A multi-gag comedy act closing a medicine show. Agent The one who works a game, especially a game that requires some skill and f inesse to sell to the marks, and most especially a rigged game. -

260 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10001 (212)889-8772 (212)889-8772 10001 N.Y

260 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10001 (212)889-8772 CONTENTS PACE PACE Anonymous, The Erotic Reader III 41 Kometani, Foumiko, Passover The Libertines 41 Lovesey, Peter, The Black Cabinet . 24 The Oyster ill 41 Parisian Nights 41 Madden, David & Peggy Bach, 33 Satanic Venus 41 Rediscoveries II Beyond Apollo 22 Ball, John, The Kiwi Target 4 Malzberg, Barry, Crossfire 15 Ballard, J.C., delta America 13 Marrs, Jim, Flesh and Blood 26 Ballard. Mignon F., Deadly Promise . 19 Mauriac, Francois. 39 Baixac, Honore de, Beatrix 30 McElroy, Joseph, The Letter Left to Me Tales 10 Beechcroft, William, Pursuit of Fear. 31 O'Mara, Leaky, Great Cat Pattern for Terror 35 Boucher, Anthony, The Compleat Pentecost, Hugh, Werewolf 33 Phillips, Robert, The Triumph of the Night 5 Brand, Christianna, Death In High Heels ,, 6 Redly, John, Marilyn'; Daughter 20 Brown, Fredric, Murder Can Be Fun 27 Rhys, Jean, Quartet 36 Carr, John Dickson, Saul, Bill D.. Animal Immortality 39 28 The De101071illel Sladek, John, The Midler-Fokker Effect 40 Most Secret 14 Stanway, Dr. Andrew, The Art of Sensual Da, Lottie & Jan Alexander, Bad Girls of Loving 13 the Silver Screen 16 Thirkell, Angela, Wild Strawberries . 7 Dolby. Richard, Ghosts for Christina' 18 Thornton, Louise, et al., Touching Fire 25 Dick, Philip K., The Zap Gun 7 van Thal, Herbert, The Mammoth Book of 20 Fitzgerald, Penelope, Innocence Great Detective Stories 12 Freudenberger, Dr. Herbert, Sit ational von Falkensee, Margarete, Blue Angel Anxiety 6 Secrets 21 Carbus, Martin, Traitors and Heroes 26 Watson, Ian, Gilbert, Michael, Chekhoes journey 17 The Doors Open 22 The Embedding 30 14 The 92nd Tiger Waugh, Hillary, Colenbock, Peter, A Death in a Timm How to Win at Rotisserie Baseball 36 Sleep Long, My Love 27 2 Personal Fouls Willeford, Charles, The Woman Chaser 40 Griffiths, John, The Good Spy 32 Wilson, Cohn. -

THE BEST of FREDRIC BROWN Edited and with an Introduction by ROBERT BLOCH NELSON DOUBLEDAY, INC. Garden City, New York COPYRIGHT

THE BEST OF FREDRIC BROWN Edited and with an Introduction by ROBERT BLOCH NELSON DOUBLEDAY, INC. Garden City, New York COPYRIGHT © 1976 BY ELIZABETH C. BROWN Introduction: A Brown Study COPYRIGHT © 1976 BY ROBERT BLOCH Published by arrangement with Ballantine Books A Division of Random House, Inc. 201 East 50th Street New York, New York 10oz2 Printed in the United States of America ACKNOWLEDGMENTS "Arena," copyright © 1944 by Street & Smith Publications, Inc., for Astounding Science Fiction, June 1944. "Imagine," copyright © 1955 by Fantasy House, Inc., for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, May 1955. "It Didn't Happen," copyright © 1963 by H.M.H. Publishing Company for Playboy, October 1963. "Recessional," copyright © 196o by Mystery Publishing Company, Inc., for Dude, March 196o. "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" (with Carl Onspaugh), copyright © 1965 by Mercury Press, Inc., for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, June 1965. "Puppet Show," copyright © x962 by H.M.H. Publishing Company for Playboy, November 1962. "Nightmare in Yellow," copyright © 1961 by Mystery Publishing Company, Inc., for Dude, May 1961. "Earthmen Bearing Gifts," copyright © 196o by Galaxy Publishing Corporation for GALAXY Magazine, June x96o. "Jaycee," copyright © 1955 by Fantasy House, Inc., for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. "Pi in the Sky," copyright '© 1945 by Standard Magazine, Inc., for Thrilling Wonder Stories, winter 1 945. "Answer," copyright © 1954 by Fredric Brown for Angels and Spaceships. "The Geezenstacks," copyright © 1943 by Popular Fiction Publishing Company for Weird Tales, September 1943. "Hall of Mirrors," copyright © 1953 by Galaxy Publishing Corporation for GALAXY Science Fiction, December 1953. "Knock," copyright © 1948 by Standard Magazines, Inc., for Thrilling Wonder Stories, December 1948. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 482 893 CS 511 870 AUTHOR Linder, Patricia E., Ed.; Sampson, Mary Beth, Ed.; Dugan, Jo Ann R., Ed.; Brancato, Barrie, Ed. TITLE Celebrating the Faces of Literacy. The Twenty-Fourth Yearbook: A Peer Reviewed Publication of the College Reading Association, 2002. [Papers from the College Reading Association Conference, 2001]. INSTITUTION College Reading Association. ISBN ISBN-1-883604-30-3 PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 275p.; For the twenty-third yearbook, see ED 480 427. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Childrens Literature; Culturally Relevant Education; Elementary Secondary Education; *Literacy; Mexican American Literature; *Reading Instruction; Reading Research; Teacher Education; Yearbooks IDENTIFIERS College Reading Association; Teaching Research; Ukraine ABSTRACT The College Reading Association believes and values literacy education for all as one way to protect people's freedoms. This 24th Yearbook celebrates the varied "faces" of literacy. The yearbook contains the following special articles: (Presidential Address) "What Is Johnny Reading? A Research Update" (Maria Valerie Gold); (Keynote Addresses) "Effective Reading Instruction: What We Know, What We Need to Know, and What We Still Need to Do" (Timothy Rasinski); "Stories That Can Change the Way We Educate" (Patricia Edwards);(J. Estill Alexander Leaders' Forum Address) "What Research Reveals about Literacy Motivation" (Linda Gambrell); (Dissertation Award) "Effects of Three Organizational Structures on the Writing and Critical Thinking of Fifth Graders" (Suzanne A. Viscovich); and (Thesis Award) "Moving Adolescent Mothers and Their Children toward the Path of Educated Independence" (Joan Scott Curtis) ."The Faces of Literacy Teachers" section contains these articles: "Comparing Career Choices and Expectations of Inservice and Preservice Teachers: A Case Survey" (Amy R. -

Issue 389, August 2018

President’s Column From the Editors Parsec Picnic July 2018 Parsec Meeting Minutes Young Adult Lecture Series - September 8, 2018 Community - TV/DVD review Fantastic Artist Of The Month It’s A Mad Universe After All Brief Bios It’s a Monster Mash: Rock and Roll and SF Review of The Gone World Parsec Meeting Schedule An Un-aired Un-produced Lackzoom Acidophilus/Parsec Radio Ad A Conversation with Curt Siodmak President’s Column I admit that a great deal of the SF of fin-du-siecle the period seems like a precursor for the SF that is to come. That is an illusion that we should overcome. I feel like it is important to take and study the works as they are presented. It provides a kind of time travel. We can always shoehorn in the crud that has come into being in the intervening years. It is pleasant to spend time in conversation with H.G. or even Jules, though my French is utterly lacking. But dig a little deeper to find the whole vein of scientific romance. George Allan England. M.P. Shiel, William Hope Hodgson, A Conan Doyle, Olaf Stapledon, George Griffith, Frank R. Stockton. The search is on for female writers of the era who, as always were there but are forgotten, Gertrude Barrows Bennett, Margaret Cavendish, Mary Shelley, Virginia Woolf(Orlando), Jane Webb Loudon. See you all in September! I’ve been absent from the last two Parsec meetings for medical reasons. I won’t tell you mine if you don’t tell me yours. -

BROWN, Fredric (William) Geboren: Cincinnati, Ohio, USA, 29 Oktober 1906

BROWN, Fredric (William) Geboren: Cincinnati, Ohio, USA, 29 oktober 1906. Overleden: Tucson, Arizona, USA, 11 maart 1972 Opleiding: University of Cincinnati avondschool; Hanover College, Indiana, 1 jaar. Carrière: ambtenaar, 1924-1936; corrector, Milwaukee Journal; freelance schrijver na 1947. Lid van: Mystery Writers of America; Writers Guild of America. Onderscheidingen: Mystery Writers of America Edgar Allan Poe award, 1948. Familie: getrouwd met 1. Helen Ruth Brown, 1929 (gescheiden, 1947, overleden, 1970); 2 zonen 2. Elizabeth Charlier, 1948. (foto: Fantastic Fiction) detectives: Ed en Am Hunter , Chicago Ed Hunter, een teenager uit Chicago en zijn oom Ambrose “Am” Hunter vormen samen een detectiveteam van het “Hunter & Hunter Detective Agency”. Ed en Am Hunter: 1. The Fabulous Clipjoint 1946 Moordkroeg Chicago 1952 Combinatie eerder in verkorte vorm verschenen odt: Dead Man’s Indemnity, in: Mystery Book 2. The Dead Ringer 1948 3. The Bloody Moonlight 1949 in engeland verschenen odt: Murder by Moonlight (1950) 4. Compliments of a Fiend 1950 De groeten van de duivel 1968 UMC 282 5. Death Has Many Doors 1951 6. The Late Lamented 1959 7. Mrs. Murphy's Underpants 1963 korte verhalen: "Before She Kills" verschenen in: Ed McBain’s Mystery Book 3 1961 “The Missing Actor andere crimetitels: Murder Can Be Fun 1948 Moord kan grappig zijn 1953 Combinatie ook verschenen odt: A Plot for Murder (1949) The Screaming Mimi 1949 Gillende Mimi 1951 Combinatie Here Comes a Candle 1950 Hier komt een kaars 1952 Combinatie Night of the Jabberwock 1951