Trawden Forest Conservation Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 400Th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and Its Meaning in 2012

The 400th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and its Meaning in 2012. Todd Andrew Bridges A thesis submitted for the degree of M.A.D. History 2016. Department of History The University of Essex 27 June 2016 1 Contents Abbreviations p. 3 Acknowledgements p. 4 Introduction: p. 5 Commemorating witch-trials: Lancashire 2012 Chapter One: p. 16 The 1612 Witch trials and the Potts Pamphlet Chapter Two: p. 31 Commemoration of the Lancashire witch-trials before 2012 Chapter Three: p. 56 Planning the events of 2012: key organisations and people Chapter Four: p. 81 Analysing the events of 2012 Conclusion: p. 140 Was 2012 a success? The Lancashire Witches: p. 150 Maps: p. 153 Primary Sources: p. 155 Bibliography: p. 159 2 Abbreviations GC Green Close Studios LCC Lancashire County Council LW 400 Lancashire Witches 400 Programme LW Walk Lancashire Witches Walk to Lancaster PBC Pendle Borough Council PST Pendle Sculpture Trail RPC Roughlee Parish Council 3 Acknowledgement Dr Alison Rowlands was my supervisor while completing my Masters by Dissertation for History and I am honoured to have such a dedicated person supervising me throughout my course of study. I gratefully acknowledge Dr Rowlands for her assistance, advice, and support in all matters of research and interpretation. Dr Rowland’s enthusiasm for her subject is extremely motivating and I am thankful to have such an encouraging person for a supervisor. I should also like to thank Lisa Willis for her kind support and guidance throughout my degree, and I appreciate her providing me with the materials that were needed in order to progress with my research and for realising how important this research project was for me. -

Pendle Education Trust Declaration of Interest

PENDLE EDUCATION TRUST DECLARATION OF INTEREST NAME DATE APPOINTED MEETINGS TERM OF NAME OF BUSINESS NATURE OF DATE APPOINTED BY ATTENDED OFFICE INTEREST INTEREST 2017/18 DECLARED 27.11.2012 PHEASEY, Rob Marsden Building Society Chief Executive November 2012 Reappointed Members 6/6 4 Years (Chair) Nelson & Colne College Governor November 2012 27.11.2016 Lancashire Education Authority Consultant October 2016 FRANKLIN, 25.10.2016 Members 6/6 4 Years Colne Park Primary Governors October 2016 David PET Quality & Standards Member December 2016 Pendle Borough Council Chief Executive LANGTON, October 2016 25.10.2016 Members 5/6 4 Years Pendle Enterprise & Company Dean April 2015 Regeneration Secretary 27.11.2012 MELTON, Nelson & Colne College Principal Jan 2013 Reappointed Members 6/6 4 Years Amanda PET Quality & Standards Member May 2016 27.11.2016 MBS Advisory Director April 2014 Coolkit Non-Exec April 2014 Director 15.04.2014 KMS Solutions Ltd Non- Exec April 2014 ROBERTS, David Reappointed Members 5/6 4 Years Director 15.09.2018 Lancashire Business Angels Director April 2014 THPlastics Non-Exec 2016 Director School Letting Solutions Non-Exec Chair 2016 15.04.2014 Managing SCOTT, Jane Members 5/6 4 Years Key Stage Teacher Supply Sept 2014 Reappointed Director 15.09.2018 Pendle Borough Council Audit Committee November 2016 Member WHATLEY, David 27.11.2016 Members 1/6 4 Years Nelson & Colne College Governor November 2016 Government Internal Audit Employee Sept 2017 Agency Riley Moss Ltd Director April 2014 Scisco Forensic Ltd Director April -

Download Boulsworth

Boulsworth Profile Contents 1. Population 1.1. 2009 Estimates 1.2. Marital Status 1.3. Ethnicity 1.4. Social Grade 2. Labour Market 2.1. Economic Activity 2.2. Economic Inactivity 2.3. Employment Occupations 2.4. Key Out-of-Work Benefits 2.4.1. Jobseeker’s Allowance Claimants 2.4.2. JSA Claimants by Age and Duration 2.4.3. Benefit Claimants 2.4.4. Income Support 3. Health 3.1. Limiting Long-Term Illness 3.2. Disability Living Allowance Claimants 3.3. Incapacity Benefit / Severe Disablement Allowance 3.4. Under 18 Conception Rates 4. Crime 5. Housing 5.1. Household Types 5.2. Tenure 5.3. People per Household 5.4. Number of Rooms per Household 5.5. Persons per Room 5.6. Housing Stock 6. Education 6.1. Key Stage 2 Results 6.2. Adult Qualifications 1 1. Population 1.1. 2009 Estimates Boulsworth Pendle England Total % % % All All 5261 0-15 893 17.0% 20.5% 18.7% 16-24 500 9.5% 12.0% 12.0% 25-49 1759 33.4% 32.0% 35.0% 50-64 / 50-59 1035 19.7% 16.4% 14.9% 65 / 60 and over 1074 20.4% 19.1% 19.3% Males All 2586 0-15 444 17.2% 21.1% 19.5% 16-24 277 10.7% 12.6% 12.5% 25-49 853 33.0% 32.2% 35.5% 50-64 609 23.5% 20.0% 18.0% 65 and over 403 15.6% 14.1% 14.5% Females All 2675 0-15 449 16.8% 19.8% 18.0% 16-24 223 8.3% 11.5% 11.6% 25-49 906 33.9% 31.9% 34.4% 50-59 426 15.9% 12.9% 12.0% 60 and over 671 25.1% 23.9% 24.0% (Source: Office for National Statistics) Main Points: - The breakdown of age groups for the Boulsworth population shows that there is a greater proportion of older residents in the ward compared to the borough and national averages. -

66 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

66 bus time schedule & line map 66 Clitheroe - Nelson Via Waddington, West Bradford, View In Website Mode Grindleton, Downham, Newchurch The 66 bus line (Clitheroe - Nelson Via Waddington, West Bradford, Grindleton, Downham, Newchurch) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chatburn Road: 7:35 AM (2) Clitheroe Town Centre: 6:40 AM - 4:15 PM (3) Nelson: 7:33 AM - 4:03 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 66 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 66 bus arriving. Direction: Chatburn Road 66 bus Time Schedule 29 stops Chatburn Road Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:35 AM Bus Station, Nelson Tuesday 7:35 AM New Scotland Road, Nelson Wednesday 7:35 AM Pendle Street, Nelson Thursday 7:35 AM Russell Street, Burnley Friday 7:35 AM Morrison, Nelson Clayton Street, Burnley Saturday Not Operational Canal Bridge, Nelson Reedyford Bridge, Burnley Nelson And Colne College, Barrowford 66 bus Info A682, Burnley Direction: Chatburn Road Stops: 29 Victoria Hotel, Barrowford Trip Duration: 44 min 1 King Edward Terrace, Barrowford Civil Parish Line Summary: Bus Station, Nelson, New Scotland Road, Nelson, Pendle Street, Nelson, Morrison, Wilton Street, Barrowford Nelson, Canal Bridge, Nelson, Nelson And Colne College, Barrowford, Victoria Hotel, Barrowford, Higher Causeway, Barrowford Wilton Street, Barrowford, Higher Causeway, Higher Causeway, Burnley Barrowford, St Thomas Church, Barrowford, Warren Drive, Barrowford, Ye Old Sparrowhawk, Wheatley St Thomas Church, Barrowford Lane, -

North West Water Authority

South Lancashire Fisheries Advisory Committee 30th June, 1976. Item Type monograph Publisher North West Water Authority Download date 29/09/2021 05:33:45 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/27037 North W est Water Authority Dawson House, Great Sankey Warrington WA5 3LW Telephone Penketh 4321 23rd June, 1976. TO: Members of the South Lancashire Fisheries Advisory Committee. (Messrs. R.D. Houghton (Chairman); T.A.F. Barnes; T.A. Blackledge; R. Farrington; J. Johnson; R.H. Wiseman; Dr. R.B. Broughton; Professor W.E. Kershaw; and the Chairman of the Authority (P.J. Liddell); The Vice-Chairman of the Authority (J.A. Foster); and the Chairman of the Regional Fisheries Advisory Committee (J.R.S. Watson)(ex officio). Dear Sir, A meeting of the SOUTH LANCASHIRE FISHERIES ADVISORY COMMITTEE will be held at 2.30 p.m. on WEDNESDAY 30TH JUNE, 1976, at the LANCASHIRE AREA OFFICE OF THE RIVERS DIVISION, 48 WEST CLIFF, PRESTON for the consideration of the following business. Yours faithfully, G.W. SHAW, Director of Administration. AGENDA 1. Apologies for absence. 2. Minutes of the last meeting (previously circulated). 3. Mitton Fishery. 4. Fisheries in the ownership of the Authority. 5. Report by Area Fisheries Officer on Fisheries Activities. 6. Pollution of Trawden Water and Colne Water - Bairdtex Ltd. 7. Seminar on water conditions dangerous to fish life. 8. Calendar of meetings 1976/77. 9. Any other business. 3 NORTH WEST WATER AUTHORITY SOUTH LANCASHIRE FISHERIES ADVISORY COMMITTEE 30TH JUNE, 1976 MITTON FISHERY 1. At the last meeting of the Regional Committee on 3rd May, a report was submitted regarding the claim of the Trustees of Stonyhurst College to the ownership of the whole of the bed of the Rivers Hodder find Ribble, insofar as the same are co- extensive with the former Manor of Aighton. -

2005 No. 170 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2005 No. 170 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The County of Lancashire (Electoral Changes) Order 2005 Made - - - - 1st February 2005 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Boundary Committee for England(a), acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(b), has submitted to the Electoral Commission(c) recommendations dated October 2004 on its review of the county of Lancashire: And whereas the Electoral Commission have decided to give effect, with modifications, to those recommendations: And whereas a period of not less than six weeks has expired since the receipt of those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Electoral Commission, in exercise of the powers conferred on them by sections 17(d) and 26(e) of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling them in that behalf, hereby make the following Order: Citation and commencement 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the County of Lancashire (Electoral Changes) Order 2005. (2) This Order shall come into force – (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005, on the day after that on which it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005. Interpretation 2. In this Order – (a) The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, established by the Electoral Commission in accordance with section 14 of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (c.41). The Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (S.I. -

Cycling in Pendle Locks

Pendle Cycle Network Links from the Canal Canal Towpath There are links from the canal to: You can now cycle on the canal all the way through Barrowford: in Colne or cycle across the playing fields Pendle, starting at Burnley through to Barnoldswick. Follow the cycle from Barrowford or the new link on Regent The canal towpath is used by Route 68 (the Pennine route across the Street. Meet up with your friends on the way Cycleway). It takes you through outstanding playing fields to to school. Cycle training is offered at many countryside with reminders of the area’s textile Barrowford. schools. heritage in Nelson and Brierfield. Pendle Links to Burnley Foulridge Heritage Follow the canal into Burnley. You can continue to Padiham on the new Greenway Places to stop on the From Wharf: There is a Centre: (along the route of the former railway line). Barrowford cycle way include: cafe here. For a day out use your bike to visit Towneley along the river to Salterforth: Stop for Hall, the National Trust’s Gawthorpe Hall, Pendle Heritage Barden Mill and Marina: a break at the canal Queens Street Mill, Thompson’s Park with its Centre. Here, you can Includes a cafe. North of the side picnic site or visit model railway and boating lake or Queen’s find out more about the marina are great views of Pendle the pub. Park with its children’s road system. area’s history. There is also Hill. a cafe at the centre. Lower Park Marina, Nelson Town Centre – You can now Brierfield: At Clogger Bridge Barnoldswick: Both the cycle through Nelson Town Centre both ways Colne: From Barrowford Locks follow come off the towpath and on Leeds and Manchester Road. -

LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION for ENGLAND N N 2 D 4 O M Round Wood Le 8 M R 65 O W L N

LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ROAD NOGGARTH S Noggarth End A N D Farm Y H A L L L A N E Final Recommendations for Ward Boundaries in Colne and Nelson PERIODIC ELECTORAL REVIEW OF PENDLE Laund House H i Farm g g e n C l o u g h Quarry (disused) September 2000 ROAD S A N D Y Cemetery H A L L L A N E W HE AT LEY WH LA EATLEY LAN NE E ROAD RO B Trough LaitheAD 6 2 4 Farm 9 OLD LAUND BOOTH WARD BARROWFORD WARD OLD LAUND BOOTH CP Laund Farm BA RR OW FO RD C R R A BARROWFORD CP O I R AD D R G E H W A L D A L I Y X R O O N A D S T APP O LEGARTH Gdns A K L A N B D A S RR P OW A B A R O F V O L R R E D T O RO O A C N D HI G K G P HE Mill R R R e C O A O n U V S d E A E W l A D e Y W C a t A e L R ST E N r LE E O R END ST P R S RE A I E D T S E T D R L L U A E C O O Y R E S Raven's Clough Wood W T N T UR E B M IS CH R G UR O CH C U ILL L C WAY College O N LOWERFORD A U T GH R S R S T Allotment Gardens T H L A O C Recreation Ground L C W A A L L E R D Lower Park Hill R A E R R 6 O 0 R 6 M P V R A RIVE 8 A A L D A U D L O HA LE D RR R CA A S R D S T O A D N NEWBRIDGE OA Cricket Ground C D R K Y RN Mills L U R A B N IS O E G AD A B D RO D A MON R RICH R O UE W AVEN F ARK O AD RTH P R O NO D R D R N r K M 6 e 5 at W I O le R d A n Pe B P L Y R AR UE A TL IN OA K A AVEN S D O D D VE K U C Waterside RE N PAR S D UE R RO R AD E Y R O A Playing er Cricket Wat D C Pendle Chamber C Ground Field Waterside H Football Ground O B P E U e U Farm Hill A R n Victoria Park L L C d T E H l O e I Industrial Estate R L N W O L R A M W a ON D T O t FOR A e D -

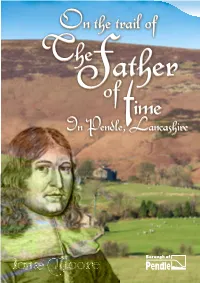

Jonas Moore Trail

1 The Pendle Witches He would walk the three miles to Burnley Grammar School down Foxendole Lane towards Jonas Moore was the son of a yeoman farmer the river Calder, passing the area called West his fascinating four and a half called John Moore, who lived at Higher White Lee Close where Chattox had lived. in Higham, close to Pendle Hill. Charged for crimes committed using mile trail goes back over 400 This was the early 17th century and John witchcraft, Chattox was hanged, alongside years of history in a little- Moore and his wife lived close to Chattox, the Alizon Device and other rival family members and known part of the Forest of Bowland, most notorious of the so called Pendle Witches. neighbours, on the hill above Lancaster, called The Moores became one of many families caught Golgotha. These were turbulent and dangerous an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. up in events which were documented in the times in Britain’s history, including huge religious It explores a hidden valley where there are world famous trial. intolerance between Protestants and Catholics. Elizabethan manor houses and evidence of According to the testimony of eighteen year Civil War the past going back to medieval times and old Alizon Device, who was the granddaughter of the alleged Pendle witch Demdike, John earlier. The trail brings to light the story of Sir Moore had quarrelled with Chattox, accusing her In 1637, at the age of 20, Jonas Moore was Jonas Moore, a remarkable mathematician of turning his ale sour. proficient in legal Latin and was appointed clerk and radical thinker that time has forgotten. -

Greenshaw Farm Off Barnoldswick Road Foulridge

Price £500,000 Greenshaw Farm Off Barnoldswick 4 2 2 3 Road Foulridge EPC Rating: F Council Tax Band: F LOCATION Travelling away from Barrowford along Barnoldswick Road, past the Cross Gaits heading towards Whitemoor Reservoir. At the 90 degree right hand turn, turn left into Gisburn track. You then have to do a U turn and proceed down Barnoldswick Road taking the first track on the left hand side. Proceed to the end and this is Greenshaw Farm. DESCRIPTION Set with one of the most idyllic views in Pendle overlooking Slipper Hill Reservoir and Lake Burwain and having views in the distance towards The Herders and Boulsworth Hill, this semi detached four bedroom farmhouse offers fantastic family living accommodation which briefly comprises substantial lounge with wood burning stove with snug area, farmhouse dining kitchen, separate dining room and garden room at ground floor level, all having outstanding South facing views to the front. At first floor level there is the master bedroom with en-suite, three further double bedrooms and a house bathroom. Externally, the property is set with patio and gardens to the front and has a detached double garage with remote roller shutter door, and a substantial garden area to the rear suitable for the growing family. The property benefits from LPG fired central heating, UPVC double glazing and in our opinion requires an internal inspection for its size and location to be fully appreciated. Conveniently located being in an elevated position within a short drive of the bars, bistros and boutiques that both Barrowford and Barnoldswick have to offer and for the commuter wishing to travel into Manchester or Preston, the M65 motorway is within a 15 minute drive. -

Proposed Colne Park High School

Admissions Policy 2020 – 2021 13510 Colne Park High School This is an academy school. Venables Avenue 11-16 Mixed Colne Head: Dr P Parkin BB8 7DP Number on Roll:1041 Oct 2018 01282 865200 Admission Number: 215 Admission number for September 2020: 215 SUMMARY OF POLICY Colne Park High is a school serving its local community. This is reflected in its admissions policy. Children will be admitted to the school in the following priority order: a. Looked after children and previously looked after children, then b. Children who have exceptionally strong medical, social or welfare reasons for admission associated with the child and/or family which are directly relevant to the school concerned, then c. Children living in the school's geographical priority area who will have a sibling (1)* in attendance at the school at the time of transfer, then d. Children who have attended for the whole of Year 5 in a primary school that is part of The PENNiNE Trust before the closing date for application, then e. Children of current employees of the school who have had a permanent contract for at least two years prior to the admissions deadline or with immediate effect if the member of staff is recruited to fill a post for which there is a demonstrable skills shortage, then f. Children living within the school's geographical priority area (2)*, then g. Children living outside of the school's geographical priority area who will have a sibling in attendance at the school at the time of transfer, then h. Children living outside of the school's geographical priority area. -

Ramblers Gems a Spring Vale Rambling Class Publication

Ramblers Gems A Spring Vale Rambling Class Publication Volume 1, Issue 13 31st July 2020 For further information or to submit a contribution email: [email protected] rule has the potential to make matters worse. The I N S I D E T H I S I SSUE increase in numbers is great for the economy but a real issue for the volunteer rescue teams. A recent 1 Be Prepared not a Risk rescue on Scafell Pike involving a family group of three and was carried out in the correctly forecast 2 Early History of the Class atrocious conditions lasting 12 hours and involved five rescue teams. 3 Around Trawden Forest 4 Tea in Witch Country / A Storm on the Moor What can you personally do as a new or even regular visitor to help the volunteer teams? 5 Watch Your Step Exercise within your limits and avoid taking risks. Be Prepared Not a Risk Know your level of skill, competence and experience and those of your group. Make sure you The Cumbria Police and the Lake District’s Mountain have the right equipment for your trip to the hills and Rescue Teams have over the last few weeks seen an valleys noting that many callouts are carried out low unprecedented amount of avoidable rescues that are down in the valley bottoms. Learn how to navigate, putting a real strain on their volunteer team members take a waterproof map and a compass, don’t rely on and this is unsustainable. The overall majority of smart phone technology, it can let you down.